PDF Facsimile Vol. 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hadith and Its Principles in the Early Days of Islam

HADITH AND ITS PRINCIPLES IN THE EARLY DAYS OF ISLAM A CRITICAL STUDY OF A WESTERN APPROACH FATHIDDIN BEYANOUNI DEPARTMENT OF ARABIC AND ISLAMIC STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Glasgow 1994. © Fathiddin Beyanouni, 1994. ProQuest Number: 11007846 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11007846 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 M t&e name of &Jla&, Most ©racious, Most iKlercifuI “go take to&at tfje iHessenaer aikes you, an& refrain from to&at tie pro&tfuts you. &nO fear gJtati: for aft is strict in ftunis&ment”. ©Ut. It*. 7. CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................4 Abbreviations................................................................................................................ 5 Key to transliteration....................................................................6 A bstract............................................................................................................................7 -

The Islamic Traditions of Cirebon

the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims A. G. Muhaimin Department of Anthropology Division of Society and Environment Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies July 1995 Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Muhaimin, Abdul Ghoffir. The Islamic traditions of Cirebon : ibadat and adat among Javanese muslims. Bibliography. ISBN 1 920942 30 0 (pbk.) ISBN 1 920942 31 9 (online) 1. Islam - Indonesia - Cirebon - Rituals. 2. Muslims - Indonesia - Cirebon. 3. Rites and ceremonies - Indonesia - Cirebon. I. Title. 297.5095982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2006 ANU E Press the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changes that the author may have decided to undertake. In some cases, a few minor editorial revisions have made to the work. The acknowledgements in each of these publications provide information on the supervisors of the thesis and those who contributed to its development. -

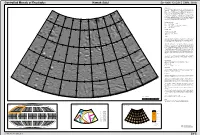

Hi-Resolution Map Sheet

Controlled Mosaic of Enceladus Hamah Sulci Se 400K 43.5/315 CMN, 2018 GENERAL NOTES 66° 360° West This map sheet is the 5th of a 15-quadrangle series covering the entire surface of Enceladus at a 66° nominal scale of 1: 400 000. This map series is the third version of the Enceladus atlas and 1 270° West supersedes the release from 2010 . The source of map data was the Cassini imaging experiment (Porco et al., 2004)2. Cassini-Huygens is a joint NASA/ESA/ASI mission to explore the Saturnian 350° system. The Cassini spacecraft is the first spacecraft studying the Saturnian system of rings and 280° moons from orbit; it entered Saturnian orbit on July 1st, 2004. The Cassini orbiter has 12 instruments. One of them is the Cassini Imaging Science Subsystem 340° (ISS), consisting of two framing cameras. The narrow angle camera is a reflecting telescope with 290° a focal length of 2000 mm and a field of view of 0.35 degrees. The wide angle camera is a refractor Samad with a focal length of 200 mm and a field of view of 3.5 degrees. Each camera is equipped with a 330° 300° large number of spectral filters which, taken together, span the electromagnetic spectrum from 0.2 60° 320° 310° to 1.1 micrometers. At the heart of each camera is a charged coupled device (CCD) detector 60° consisting of a 1024 square array of pixels, each 12 microns on a side. MAP SHEET DESIGNATION Peri-Banu Se Enceladus (Saturnian satellite) 400K Scale 1 : 400 000 43.5/315 Center point in degrees consisting of latitude/west longitude CMN Controlled Mosaic with Nomenclature Duban 2018 Year of publication IMAGE PROCESSING3 Julnar Ahmad - Radiometric correction of the images - Creation of a dense tie point network 50° - Multiple least-square bundle adjustments 50° - Ortho-image mosaicking Yunan CONTROL For the Cassini mission, spacecraft position and camera pointing data are available in the form of SPICE kernels. -

John FT Keane's Late Nineteenth Century Ḥajj by Nicole J. Crisp BA

Out of Obscurity: John F. T. Keane’s Late Nineteenth Century Ḥajj by Nicole J. Crisp B.A. in History, May 2014, University of Nevada, Las Vegas B.A. in Anthropology, May 2014, University of Nevada, Las Vegas A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts May 21, 2017 Thesis directed by Dina Rizk Khoury Professor of History © Copyright 2017 by Nicole J. Crisp All rights reserved ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professors Khoury and Blecher specifically for guiding me through the journey of writing this thesis as well as the rest of the George Washington University’s History Department whose faculty, students, and staff have created an unforgettable learning experience over the past three years. Further, I would like to thank my co-workers, both in College Park, Maryland, and Washington, D.C., some of whom have become like family to me and helped me through thick and thin. I would also be remiss if I were not to thank my best friend, Danielle Romero, who mentioned me in the acknowledgements page of her thesis so I effectively must mention her here and quote a line from series that got me through the end of this thesis, “Bang.” I would also like to express my gratitude to my Aunt Joy Harris who has been a constant fountain of encouragement. Finally, I would like to thank my parents, Larry and Dianne, to whom this thesis is dedicated. -

A Global Shape Model for Saturn's Moon Enceladus

ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume V-3-2020, 2020 XXIV ISPRS Congress (2020 edition) A GLOBAL SHAPE MODEL FOR SATURN’S MOON ENCELADUS FROM A DENSE PHOTOGRAMMETRIC CONTROL NETWORK M. T. Bland*, L. A. Weller., D. P. Mayer, B. A. Archinal Astrogeology Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, 2255 N. Gemini Dr., Flagstaff, AZ 86001 ([email protected]) Commission III, ICWG III/II KEY WORDS: Enceladus, Shape Model, Topography, Photogrammetry ABSTRACT: A planetary body’s global shape provides both insight into its geologic evolution, and a key element of any Planetary Spatial Data Infrastructure (PSDI). NASA’s Cassini mission to Saturn acquired more than 600 moderate- to high-resolution images (<500 m/pixel) of the small, geologically active moon Enceladus. The moon’s internal global ocean and intriguing geology mark it as a candidate for future exploration and motivates the development of a PSDI. Recently, two PSDI foundational data sets were created: geodetic control and orthoimages. To provide the third foundational data set, we generate a new shape model for Enceladus from Cassini images and a dense photogrammetric control network (nearly 1 million tie points) using the U.S. Geological Survey’s Integrated Software for Imagers and Spectrometers (ISIS) and the Ames Stereo Pipeline (ASP). The new shape model is near-global in extent and gridded to 2.2 km/pixel, ~50 times better resolution than previous global models. Our calculated triaxial shape, rotation rate, and pole orientation for Enceladus is consistent with current International Astronomical Union (IAU) values to within the error; however, we determined a o new prime meridian offset (Wo) of 7.063 . -

Encounters at the Seams

Jen Barrer-Gall 5 April 2013 Advisor: Professor William Leach Second Reader: Professor Christopher Brown Encounters at the Seams English "Self Fashioning" in the Ottoman World, 1563-1718 1 Acknowledgments I thank Professor William Leach for his encouragement and help throughout this process. His thesis seminar was a place in which students could freely discuss their papers and give advice to their peers. Moreover, I thank Professor Leach for reminding us that history is as much about the story we are telling as it is about whom we are as individuals. I also thank my second reader, Professor Christopher Brown, whose course "England and the Wider World" inspired me to major in history. He has always been patient and supportive, and I cannot thank him enough for all his advice relating to reading, analyzing, and writing history. 2 Introduction 4 An Eastern Door Opens Chapter I 11 Traders and Travelers on the Ottoman Stage An Appetite for Knowledge Ottoman Dress as a Business Tool Unwritten Customs Moments of Vulnerability, Moments of Pride Chapter II 27 Englishmen in Captivity: How they coped and how they escaped Telling their Tale Seized, Stripped, and Vulnerable The Great Escape Performative Conversion Chapter III 39 Renegades at Sea, on Land, and on the Stage A Place of Intrigue The Seventeenth-Century Imagination Becoming East Conclusion 55 Changing Landscapes Appendix 60 Bibliography 65 3 Introduction An Eastern Door Opens In 1575, six years before Queen Elizabeth I signed the Levant Company charter, English merchants ventured to Constantinople to renew an Eastern trade that had been dormant for nearly twenty years. -

Why They Died Civilian Casualties in Lebanon During the 2006 War

September 2007 Volume 19, No. 5(E) Why They Died Civilian Casualties in Lebanon during the 2006 War Map: Administrative Divisions of Lebanon .............................................................................1 Map: Southern Lebanon ....................................................................................................... 2 Map: Northern Lebanon ........................................................................................................ 3 I. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... 4 Israeli Policies Contributing to the Civilian Death Toll ....................................................... 6 Hezbollah Conduct During the War .................................................................................. 14 Summary of Methodology and Errors Corrected ............................................................... 17 II. Recommendations........................................................................................................ 20 III. Methodology................................................................................................................ 23 IV. Legal Standards Applicable to the Conflict......................................................................31 A. Applicable International Law ....................................................................................... 31 B. Protections for Civilians and Civilian Objects ...............................................................33 -

Where Do the Multi-Religious Origins of Islam Lie? a Topological Approach to a Wicked Problem

9 (2019) Article 6: 165-210 Where Do the Multi-Religious Origins of Islam Lie? A Topological Approach to a Wicked Problem MANFRED SING Leibniz Institute of European History, Mainz, Germany This contribution to Entangled Religions is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC BY 4.0 International). The license can be accessed at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode. Entangled Religions 9 (2019) http://doi.org/10.13154/er.v9.2019.165–210 Where Do the Multi-Religious Origins of Islam Lie? Where Do the Multi-Religious Origins of Islam Lie? A Topological Approach to a Wicked Problem MANFRED SING Leibniz Institute of European History ABSTRACT The revelation of Islam in Arabic, its emergence in the Western Arabian Peninsula, and its acquaintance with Biblical literature seem to be clear indications for Islam’s birthplace and its religious foundations. While the majority of academic scholarship accepts the historicity of the revelation in Mecca and Medina, revisionist scholars have started questioning the location of early Islam with increasing fervour in recent years. Drawing on the isolation of Mecca and the lack of clear references to Mecca in ancient and non-Muslim literature before the mid-eighth century, these scholars have cast doubt on the claim that Mecca was already a trading outpost and a pilgrimage site prior to Islam, questioning the traditional Islamic and Orientalist view. Space, thus, plays a prominent role in the debate on the origins of Islam, although space is almost never conceptually discussed. In the following paper, I challenge the limited understanding of space in revisionist as well as mainstream scholarship. -

Volume 2 February 2021 Editor’S Note

Volume 2 February 2021 Editor’s Note “Imagination is more important than knowledge” -Albert Einstein 2020- the challenging year, that served us plates of moral lessons has finally bid its farewell. The New Year welcomes us with new hope of healing and blossoming while the AVS community brings to you the second edition of Spectrum. They say that learning never stops be it in the midst of a global pandemic or through this compilation of creativity by our very own fellow aviators. As you turn pages enjoy the journey through wonderful space, explore its hidden treasures and mysteries, delve into the wonderful tale of Jupiter and Saturn’s reunion, dig into the possibilities of life beyond and much more. I urge you to fully savor the knowledge embedded, in the imagination of the students as you flip through these pages. Wishing you a pleasurable read ! Magdolina R. S. Lepcha WHAT’S INSIDE To study pH level of Khar made Brain Gym from different varieties of Banana Peel Kids’ Corner Some fiction – Some reality! Enceladus- the search for life Ghost Water Star Wars Is Now DIY (Hand Sanitizer) Hmour in Science CRISPR/CAS9 Graphene- the wonder material 1 | SPECTRUM VOLUME-2 To study pH level of Khar made from different varieties of Banana Peel Priyanchi Sarma, 11SB and Dr. Alpana Dey ABSTRACT: Kolakhar, prepared from Banana peel; is an alkaline water that has been used by people of Assam, since times immortal. Along with its routine use as additive in cooking, Kolakhar had been used to treat various ailment due to its high alkaline content. -

Routledge Handbook of U.S. Counterterrorism and Irregular

‘A unique, exceptional volume of compelling, thoughtful, and informative essays on the subjects of irregular warfare, counter-insurgency, and counter-terrorism – endeavors that will, unfortunately, continue to be unavoidable and necessary, even as the U.S. and our allies and partners shift our focus to Asia and the Pacific in an era of renewed great power rivalries. The co-editors – the late Michael Sheehan, a brilliant comrade in uniform and beyond, Liam Collins, one of America’s most talented and accomplished special operators and scholars on these subjects, and Erich Marquardt, the founding editor of the CTC Sentinel – have done a masterful job of assembling the works of the best and brightest on these subjects – subjects that will continue to demand our attention, resources, and commitment.’ General (ret.) David Petraeus, former Commander of the Surge in Afghanistan, U.S. Central Command, and Coalition Forces in Afghanistan and former Director of the CIA ‘Terrorism will continue to be a featured security challenge for the foreseeable future. We need to be careful about losing the intellectual and practical expertise hard-won over the last twenty years. This handbook, the brainchild of my late friend and longtime counter-terrorism expert Michael Sheehan, is an extraordinary resource for future policymakers and CT practitioners who will grapple with the evolving terrorism threat.’ General (ret.) Joseph Votel, former commander of US Special Operations Command and US Central Command ‘This volume will be essential reading for a new generation of practitioners and scholars. Providing vibrant first-hand accounts from experts in counterterrorism and irregular warfare, from 9/11 until the present, this book presents a blueprint of recent efforts and impending challenges. -

Pitts Story for Website

Joseph Pitts of Exon: the first Englishman in Mecca By Ghee Bowman, community researcher at Exeter Global Centre With thanks and acknowledgements to Paul Auchterlonie Joseph Pitts was born in Exeter around 1663, shortly after the restoration of Charles II. At the age of 15, Joseph was taken with a desire to travel - “my genius led me to be a sailor” as he puts it - and enrolled as one of a crew of six on the fishing boat Speedwell under the captain, George Taylor. They sailed on Easter Tuesday 1678, bound for the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, where they intended to catch fish for sale in Spain. In the Bay of Biscay, however, the boat was captured by Barbary pirates. The pirates sank the boat, as they subsequently did many others. They weren’t interested in the boat or its cargo, but only the people on it. What were Barbary pirates? Also known as Corsairs, they were privateers from ports in North Africa, who sailed the Mediterranean in search of people they could capture and sell as slaves. It is estimated that they captured around a million people from the 16 th to the 19 th century. Until the 17 th century they used galleys, powered by oars, and so were restricted to the Mediterranean. Around 1610 however, they developed the broad sails that enabled them to go into the Atlantic, due to the help of English sea captains who had left the country after Queen Elizabeth’s death. Kent-born Captain Jack Ward, for example, was active in Tunis at the time under the name Yusuf Reis. -

Liste Des Participants

World Heritage 43 COM WHC/19/43.COM/INF.2 Paris, July/ juillet 2019 Original: English / French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L'EDUCATION, LA SCIENCE ET LA CULTURE CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE CONVENTION CONCERNANT LA PROTECTION DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL, CULTUREL ET NATUREL WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE/ COMITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL Forty-third session / Quarante-troisième session Baku, Republic of Azerbaijan / Bakou, République d’Azerbaïdjan 30 June – 10 July 2019 / 30 juin - 10 juillet 2019 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS LISTE DES PARTICIPANTS This list is based on the information provided by participants themselves, however if you have any corrections, please send an email to: [email protected] Cette liste est établie avec des informations envoyées par les participants, si toutefois vous souhaitez proposer des corrections merci d’envoyer un email à : [email protected] Members of the Committee / Membres du Comité ............................................................ 5 Angola ............................................................................................................................... 5 Australia ............................................................................................................................ 5 Azerbaijan ......................................................................................................................... 7 Bahrain .............................................................................................................................