THE LIFE of SALADIN AD 1138-1193 by Stanley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hadith and Its Principles in the Early Days of Islam

HADITH AND ITS PRINCIPLES IN THE EARLY DAYS OF ISLAM A CRITICAL STUDY OF A WESTERN APPROACH FATHIDDIN BEYANOUNI DEPARTMENT OF ARABIC AND ISLAMIC STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Glasgow 1994. © Fathiddin Beyanouni, 1994. ProQuest Number: 11007846 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11007846 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 M t&e name of &Jla&, Most ©racious, Most iKlercifuI “go take to&at tfje iHessenaer aikes you, an& refrain from to&at tie pro&tfuts you. &nO fear gJtati: for aft is strict in ftunis&ment”. ©Ut. It*. 7. CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................4 Abbreviations................................................................................................................ 5 Key to transliteration....................................................................6 A bstract............................................................................................................................7 -

The Islamic Traditions of Cirebon

the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims A. G. Muhaimin Department of Anthropology Division of Society and Environment Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies July 1995 Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Muhaimin, Abdul Ghoffir. The Islamic traditions of Cirebon : ibadat and adat among Javanese muslims. Bibliography. ISBN 1 920942 30 0 (pbk.) ISBN 1 920942 31 9 (online) 1. Islam - Indonesia - Cirebon - Rituals. 2. Muslims - Indonesia - Cirebon. 3. Rites and ceremonies - Indonesia - Cirebon. I. Title. 297.5095982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2006 ANU E Press the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changes that the author may have decided to undertake. In some cases, a few minor editorial revisions have made to the work. The acknowledgements in each of these publications provide information on the supervisors of the thesis and those who contributed to its development. -

March 21–25, 2016

FORTY-SEVENTH LUNAR AND PLANETARY SCIENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL SESSIONS MARCH 21–25, 2016 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel and Convention Center The Woodlands, Texas INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Stephen Mackwell, Lunar and Planetary Institute Eileen Stansbery, NASA Johnson Space Center PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS David Draper, NASA Johnson Space Center Walter Kiefer, Lunar and Planetary Institute PROGRAM COMMITTEE P. Doug Archer, NASA Johnson Space Center Nicolas LeCorvec, Lunar and Planetary Institute Katherine Bermingham, University of Maryland Yo Matsubara, Smithsonian Institute Janice Bishop, SETI and NASA Ames Research Center Francis McCubbin, NASA Johnson Space Center Jeremy Boyce, University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Needham, Carnegie Institution of Washington Lisa Danielson, NASA Johnson Space Center Lan-Anh Nguyen, NASA Johnson Space Center Deepak Dhingra, University of Idaho Paul Niles, NASA Johnson Space Center Stephen Elardo, Carnegie Institution of Washington Dorothy Oehler, NASA Johnson Space Center Marc Fries, NASA Johnson Space Center D. Alex Patthoff, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Cyrena Goodrich, Lunar and Planetary Institute Elizabeth Rampe, Aerodyne Industries, Jacobs JETS at John Gruener, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA Johnson Space Center Justin Hagerty, U.S. Geological Survey Carol Raymond, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lindsay Hays, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Paul Schenk, -

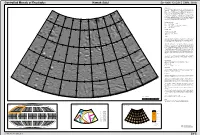

Hi-Resolution Map Sheet

Controlled Mosaic of Enceladus Hamah Sulci Se 400K 43.5/315 CMN, 2018 GENERAL NOTES 66° 360° West This map sheet is the 5th of a 15-quadrangle series covering the entire surface of Enceladus at a 66° nominal scale of 1: 400 000. This map series is the third version of the Enceladus atlas and 1 270° West supersedes the release from 2010 . The source of map data was the Cassini imaging experiment (Porco et al., 2004)2. Cassini-Huygens is a joint NASA/ESA/ASI mission to explore the Saturnian 350° system. The Cassini spacecraft is the first spacecraft studying the Saturnian system of rings and 280° moons from orbit; it entered Saturnian orbit on July 1st, 2004. The Cassini orbiter has 12 instruments. One of them is the Cassini Imaging Science Subsystem 340° (ISS), consisting of two framing cameras. The narrow angle camera is a reflecting telescope with 290° a focal length of 2000 mm and a field of view of 0.35 degrees. The wide angle camera is a refractor Samad with a focal length of 200 mm and a field of view of 3.5 degrees. Each camera is equipped with a 330° 300° large number of spectral filters which, taken together, span the electromagnetic spectrum from 0.2 60° 320° 310° to 1.1 micrometers. At the heart of each camera is a charged coupled device (CCD) detector 60° consisting of a 1024 square array of pixels, each 12 microns on a side. MAP SHEET DESIGNATION Peri-Banu Se Enceladus (Saturnian satellite) 400K Scale 1 : 400 000 43.5/315 Center point in degrees consisting of latitude/west longitude CMN Controlled Mosaic with Nomenclature Duban 2018 Year of publication IMAGE PROCESSING3 Julnar Ahmad - Radiometric correction of the images - Creation of a dense tie point network 50° - Multiple least-square bundle adjustments 50° - Ortho-image mosaicking Yunan CONTROL For the Cassini mission, spacecraft position and camera pointing data are available in the form of SPICE kernels. -

PDF Facsimile Vol. 2

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com PersonalnarrativeofapilgrimagetoEl-MedinahandMeccah RichardFrancisBurton W/. <J\ From the library of Lloyd Cabot Ttriggs 1909 - 1975 Tozzer Library PEABODY MUSEUM HARVARD UNIVERSITY f. THE PILGRIM. PERSONAL NARRATIVE PILGKIMAGE TO EL-MEDINAH AND MECCAH. BY RICHARD F, BURTON, LIEUTENANT BOMBAY ARHY. " Om aotlons of Mecca must be (lrnwn from the Arabluis -, u no unbclierer is permitted to enter the city, our traveller* are eilent." — Gibbon, chap. 50. IN THREE VOLUMES. VOL. II. — EL-MEDINAH. LONDON: LONGMAN, BROWN, GREEN, AND LONGMANS. 18H5. '/•'.< Author r«ftn«4 to hitnsetfttic right o/aufAorumff a TransIatfon ofthiM Work.] Bool. R-m>^'*fsV •• RECEIVED QTO 1 r ^f( _PEABODY "MUSEUM XiONDON I A. tuid G. A. SromswooDE, New. street-Squure. ^J \ CONTENTS OF THE SECOND VOLUME. CHAPTER XIV. PAGE From Bir Abbas to El Mcdinah - - - 1 CHAPTER XV. Through the Suburb of El Medinah to Hamid's House - - - - - 28 CHAPTER XVI. A Visit to the Prophet's Tomb - . - 56 CHAPTER XVII. An Essay towards the History of the Prophet's Mosque - - - - 113 CHAPTER XVIII. El Medinah 162 CHAPTER XIX. A Ride to the Mosque of Kuba - - - 195 CHAPTER XX. The Visitation of Hamzah's Tomb - - 223 CHAPTER XXI. The People of El Medinah - - - 254 IV CONTENTS. CHAPTER XXII. FACE A Visit to the Saints' Cemetery - - - 295 POSTSCRIPT - 329 APPENDIX I. Specimen of a Murshid's Diploma, in the Kadiri Oriler of the Mystic Craft El Tasawwuf - - - 341 APPENDIX II. -

Radio Occultation of Saturn's Rings with the Cassini Spacecraft: Ring Microstructure Inferred from Near-Forward Radio Wave

RADIO OCCULTATION OF SATURN’S RINGS WITH THE CASSINI SPACECRAFT: RING MICROSTRUCTURE INFERRED FROM NEAR-FORWARD RADIO WAVE SCATTERING A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Fraser Stuart Thomson July 2010 © 2010 by Fraser Stuart Thomson. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/pb657pg3502 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Howard Zebker, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Per Enge I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Essam Marouf Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii iv Abstract The Cassini spacecraft is a robotic probe sent from Earth to orbit and explore the planet Saturn, its moons, and its expansive ring system. -

Mcleods0809.Pdf (15.34Mb)

ISOSTATICALLY COMPENSATED EXTENSIONAL TECTONICS ON ENCELADUS by Scott Stuart McLeod A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Earth Sciences MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana May 2009 ©COPYRIGHT by Scott Stuart McLeod 2009 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Scott Stuart McLeod This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citation, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. David R. Lageson Approved for the Department of Earth Sciences Stephan G. Custer Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Dr. Carl A. Fox iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Scott Stuart McLeod May 2009 iv DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my parents, Grace and Rodney McLeod, for their tireless enthusiasm, encouragement and support, and to my friends and colleagues who never stopped believing in me – you know who you are. -

The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night – Volume 10

THE BOOK OF THE THOUSAND NIGHTS AND A NIGHT A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights Entertainments by Richard F. Burton VOLUME TEN The Dunyazad Digital Library www.dunyazad-library.net The Book Of The Thousand Nights And A Night A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights Entertainments by Richard F. Burton First published 1885–1888 Volume Ten The Dunyazad Digital Library www.dunyazad-library.net The Dunyazad Digital Library (named in honor of Shahrazad’s sister) is based in Austria. According to Austrian law, the text of this book is in the public domain (“gemeinfrei”), since all rights expire 70 years after the author’s death. If this does not apply in the place of your residence, please respect your local law. However, with the exception of making backup or printed copies for your own personal use, you may not copy, forward, reproduce or by any means publish this e- book without our previous written consent. This restriction is only valid as long as this e-book is available at the www.dunyazad-library.net website. This e-book has been carefully edited. It may still contain OCR or transcription errors, but also intentional deviations from the available printed source(s) in typog- raphy and spelling to improve readability or to correct obvious printing errors. A Dunyazad Digital Library book Selected, edited and typeset by Robert Schaechter First published November 2014 Release 1.0 · November 2014 2 To His Excellency Yacoub Artin Pasha, Minister of Instruction, etc. etc. etc. Cairo. My Dear Pasha, During the last dozen years, since we first met at Cairo, you have done much for Egyptian folk-lore and you can do much more. -

Women Writing Gender, Sexuality and Violence in the Novel of the Lebanese Civil War

Telling Stories of Pain: Women Writing Gender, Sexuality and Violence in the Novel of the Lebanese Civil War by Khaled M. Al-Masri A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Near Eastern Studies) in the University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor Anton Shammas, Chair Professor Patricia Smith Yaeger Associate Professor Kathryn Babayan Associate Professor Carol B. Bardenstein For my parents ii Acknowledgements This dissertation could never have been written without the help and support of many people. First and foremost, I am deeply thankful to my advisor, Professor Anton Shammas, for his thorough guidance throughout this process. This dissertation was shaped by his thoughtful comments, insightful critiques and careful readings, both formally and informally during our many conversations. I am also very grateful to the members of my dissertation committee, who offered their help, support and understanding. I thank Professors Carol Bardenstein, Kathryn Babayan and Patricia Yaeger for taking the time to read my dissertation and aid me in the development of my ideas with their invaluable questions, suggestions and comments. I would like to thank Professor Raji Rammuny for being a great mentor, always ready with sound advice and enthusiastic encouragement. Many thanks go to Angela Beskow as well for her guidance, patience and logistical assistance. I am deeply indebted to Allison Blecker for her immeasurable help throughout the writing of this dissertation. She read numerous drafts and I am enormously grateful for her endless encouragement and unflagging support. Finally, my family holds a special place in my heart. -

A B C Chd Dhe FG Ghhi J Kkh L M N P Q RS Sht Thu V WY Z Zh

Arabic & Fársí transcription list & glossary for Bahá’ís Revised September Contents Introduction.. ................................................. Arabic & Persian numbers.. ....................... Islamic calendar months.. ......................... What is transcription?.. .............................. ‘Ayn & hamza consonants.. ......................... Letters of the Living ().. ........................ Transcription of Bahá ’ı́ terms.. ................ Bahá ’ı́ principles.. .......................................... Meccan pilgrim meeting points.. ............ Accuracy.. ........................................................ Bahá ’u’llá h’s Apostles................................... Occultation & return of th Imám.. ..... Capitalization.. ............................................... Badı́‘-Bahá ’ı́ week days.. .............................. Persian solar calendar.. ............................. Information sources.. .................................. Badı́‘-Bahá ’ı́ months.. .................................... Qur’á n suras................................................... Hybrid words/names.. ................................ Badı́‘-Bahá ’ı́ years.. ........................................ Qur’anic “names” of God............................ Arabic plurals.. ............................................... Caliphs (first ).. .......................................... Shrine of the Bá b.. ........................................ List arrangement.. ........................................ Elative word -

Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics

Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics Activity Report 2017 University of Colorado at Boulder 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Voyager Mission Anniversary ---------------------------------------- 2 Cassini Mission ----------------------------------------------------------- 5 A Brief History ------------------------------------------------------------ 7 Missions and Projects to 2020 ----------------------------------------- 7 A Message from the Director ------------------------------------------ 8 LASP Organization Chart ---------------------------------------------- 9 LASP Appropriated Funding ----------------------------------------- 10 LASP Scientists ------------------------------------------------------------ 11 Visiting Scholars ---------------------------------------------------------- 11 2017 Retirees --------------------------------------------------------------- 11 Engineering/Missions Ops/Administration/Science ---------- 12 Affiliates -------------------------------------------------------------------- 16 EMM (Emirates Mars Mission) Collaborators --------------------- 18 2017 Ph.D. Graduates ---------------------------------------------------- 19 Students --------------------------------------------------------------------- 20 Faculty Scientific Research Interests --------------------------------- 23 Faculty Honors/Awards ----------------------------------------------- 28 Courses Taught by LASP Faculty ------------------------------------ 28 Colloquia and Informal Talks ----------------------------------------- 28 Publications ---------------------------------------------------------------- -

Saddam's Generals: Perspectives of the Iran-Iraq

SADDAM’S GENERALS Perspectives of the Iran-Iraq War Kevin M. Woods, Williamson Murray, Elizabeth A. Nathan, Laila Sabara, Ana M. Venegas SADDAM’S GENERALS SADDAM’S GENERALS Perspectives of the Iran-Iraq War Kevin M. Woods, Williamson Murray, Elizabeth A. Nathan, Laila Sabara, Ana M. Venegas Institute for Defense Analyses 2011 Final July 2010 IDA Document D-4121 Log: H 10-000765/1 Copy This work was conducted under contract DASW01-04-C-003, Task ET-8-2579, “Study on Military History (Project 1946—Phase II)” for the National Intelligence Council. The publication of this IDA document does not indicate endorsement by the Department of Defense, nor should the contents be construed as reflecting the official position of the Agency. © 2010 Institute for Defense Analyses, 4850 Mark Center Drive, Alexandria, Virginia 22311-1882 • (703) 845-2000. This material may be reproduced by or for the U.S. Government pursuant to the copyright license under the clause at DFARS 252.227-7013 (November 1995). Contents Foreword............................................................................................................................................ vii Introduction.......................................................................................................................................... 1 Summary and Analysis........................................................................................................................ 5 Background ..................................................................................................................................