From Slave to King Daniel Perret

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gouverneur-Generaals Van Nederlands-Indië in Beeld

JIM VAN DER MEER MOHR Gouverneur-generaals van Nederlands-Indië in beeld In dit artikel worden de penningen beschreven die de afgelo- pen eeuwen zijn geproduceerd over de gouverneur-generaals van Nederlands-Indië. Maar liefs acht penningen zijn er geslagen over Bij het samenstellen van het overzicht heb ik de nu zo verguisde gouverneur-generaal (GG) voor de volledigheid een lijst gemaakt van alle Jan Pieterszoon Coen. In zijn tijd kreeg hij geen GG’s en daarin aangegeven met wie er penningen erepenning of eremedaille, maar wel zes in de in relatie gebracht kunnen worden. Het zijn vorige eeuw en al in 1893 werd er een penning uiteindelijk 24 van de 67 GG’s (niet meegeteld zijn uitgegeven ter gelegenheid van de onthulling van de luitenant-generaals uit de Engelse tijd), die in het standbeeld in Hoorn. In hetzelfde jaar prijkte hun tijd of ervoor of erna met één of meerdere zijn beeltenis op de keerzijde van een prijspen- penningen zijn geëerd. Bij de samenstelling van ning die is geslagen voor schietwedstrijden in dit overzicht heb ik ervoor gekozen ook pennin- Den Haag. Hoe kan het beeld dat wij van iemand gen op te nemen waarin GG’s worden genoemd, hebben kantelen. Maar tegelijkertijd is het goed zoals overlijdenspenningen van echtgenotes en erbij stil te staan dat er in andere tijden anders penningen die ter gelegenheid van een andere naar personen en functionarissen werd gekeken. functie of gelegenheid dan het GG-schap zijn Ik wil hier geen oordeel uitspreken over het al dan geslagen, zoals die over Dirck Fock. In dit artikel niet juiste perspectief dat iedere tijd op een voor- zal ik aan de hand van het overzicht stilstaan bij val of iemand kan hebben. -

An Abode of Islam Under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms Among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar

JIOWSJournal of Indian Ocean World Studies An Abode of Islam under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar Mahmood Kooria To cite this article: Kooria, Mahmood. “An Abode of Islam Under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar.” Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies, 1 (2017), pp. 89-109. More information about the Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies can be found at: jiows.mcgill.ca © Mahmood Kooria. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Li- cense CC BY NC SA, which permits users to share, use, and remix the material provide they give proper attribu- tion, the use is non-commercial, and any remixes/transformations of the work are shared under the same license as the original. Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies, 1 (2017), pp. 89-109. © Mahmood Kooria, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 | 89 An Abode of Islam under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar Mahmood Kooria* Leiden University, Netherlands ABSTRACT When Vasco da Gama asked the Zamorin (ruler) of Calicut to expel from his domains all Muslims hailing from Cairo and the Red Sea, the Zamorin rejected it, saying that they were living in his kingdom “as natives, not foreigners.” This was a marker of reciprocal understanding between Muslims and Zamorins. When war broke out with the Portuguese, Muslim intellectuals in the region wrote treatises and delivered sermons in order to mobilize their community in support of the Zamorins. -

What Happened to Sayf Al-Rijal?

Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Vol. 168, no. 1 (2012), pp. 100-111 URL: http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/btlv URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-101720 Copyright: content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License ISSN: 0006-2294 SHER BANU A.L. KHAN What happened to Sayf al-Rijal? Who was Sayf al-Rijal? Sayf al-Rijal is a little-known Sheikh al-Islam, the highest religious appointee in the seventeenth-century court of Aceh Dar al-Salam.1 He replaced the re- nowned Sheikh Nur al-Din in 1643 and in turn was succeeded by another fa- mous ulama, Abd al- Ra’uf al-Sinkili, in 1661. While much ink and paper have been devoted to illuminating the lives and writings of al-Raniri and al-Sinkili, curiously al-Rijal has remained in total eclipse. This darkness shrouding al-Ri- jal is all the more surprising since he appears to have been Sheikh al-Islam for eighteen years, longer than his predecessor al-Raniri, who held the post for only six years from 1637 to 1643. Furthermore, Al-Rijal was no less involved in religious controversies whose echoes reverberated in the whole of the Ma- lay world. These violent and at times bloody debates were between the more orthodox shari’a-oriented ulamas and the more mystical-syncretistic ulamas.2 In Aceh, this controversy was exemplified by the bloody debate between the more orthodox shari’a-inclined al-Raniri and the disciples of the more philo- sophical mystical-oriented Shams al-Din al-Sumatra’i (died 1630), believed to be the Sheikh al-Islam in Aceh during the reign of Iskandar Muda (reigned 1607-1636). -

Changing Policies Over Timber Supply and Its Potential Impacts to the Furniture Industries of Jepara, Indonesia

JMHT Vol. XXI, (1): 36-44, April 2015 Scientific Article EISSN: 2089-2063 ISSN: 2087-0469 DOI: 10.7226/jtfm.21.1.36 Changing policies over timber supply and its potential impacts to the furniture industries of Jepara, Indonesia Dodik Ridho Nurrochmat1*, Efi Yuliati Yovi1, Oki Hadiyati2, Muhammad Sidiq3, James Thomas Erbaugh44 1Department of Forest Management, Faculty of Forestry, Bogor Agricultural University, Academic Ring Road, Campus IPB Dramaga, PO Box 168, Bogor, Indonesia 16680 2Ministry of Environment and Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia, Gedung Manggala Wanabakti Block I, 3th Floor Gatot Subroto, Senayan, Jakarta, Indonesia 10270 3CBFM and Agroforestry GIZ BIOCLIME, Jl. Jendral Sudirman Km. 3,5 No 2837 Palembang, Indonesia 4School of Natural Resources and Environment, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA Received March 2, 2015/Accepted April 28, 2015 Abstract Though some scholars argue that Indonesian wood furniture industries are in decline, these industries remain a driving force for regional and national economies. Indonesian wood furniture has a long value chain, including: forest farmers, log traders, artisans, and furniture outlets. In Jepara, Central Java, wood furniture industries contain significant regional and historical importance. Jeparanese wood furniture industries demonstrated great resilience during the economic crisis in the late nineties. Although they were previously able to withstand the pressures of economic crisis, the enactment of Minister of Forestry Regulation (MoFor Reg.) 7/2009 on wood allocation for local use -as one of the implementing regulation of Decentralization Law 32/2004- causes a potential reduction of wood supply to Jepara. Since September 30th, 2014, however, the constellation of domestic timber politics has changed due to the new decentralization law (23/2014), which shifted most regulations on forest and forest products from the regency to the province. -

Economic Inequality and Inter-Island Shipping Policy in Indonesia Until the 1960S

E3S Web of Conferences 202, 07070 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202020207070 ICENIS 2020 Java and Outer Island: Economic Inequality and Inter-Island Shipping Policy in Indonesia Until the 1960s Haryono Rinardi* Department of History ;Faculty of Humanity; Diponegoro University Abstract. This article tries to explain the relationship between economic inequality in Java and outer Java, also the inter-island shipping policy in Indonesia until the 1960s by using the historical methods. This study proves that the inequality had occurred since the colonial era when the Dutch colonial government focused on developing infrastructure on Java as the center of its government. When withdrawn again, inequality has occurred since pre-colonial times. The inter-island shipping policy that places Java as the center of shipping has increasingly encouraged economic inequality. Keywords: Economic Inequality; Inter-island Shipping; Historical Methods; Java and Outer Java; Colonial Era 1 Introduction Inequality and dichotomy between Java Island and other regions in Indonesia are not only real but visible in terminology. The Colonial Government referred to areas outer Java as Buitenbezittingen and then buitengewesten. [1] Therefore it is not surprising that Clifford Geertz, an anthropologist, distinguishes the interior regions of Central Java and East Java and as Indonesia within. Other areas have referred to as outer Indonesia [2]. Obviously, the two regions have different types. The Indonesian region has culturally influenced by Hindu- Buddhist culture. It can seen from the existence of various temples in the P. Java region. Another influence is the persistence of the presence of cultural arts, which is a relic of Hindu- Buddhist culture in Indonesia, such as the Ramayana and Mahabarata epics. -

The Depictions of the Spice That Circumnavigated the Globe. the Contribution of Garcia De Orta's Colóquios Dos Simples (Goa

The depictions of the spice that circumnavigated the globe. The contribution of Garcia de Orta’s Colóquios dos Simples (Goa, 1563) to the construction of an entirely new knowledge about cloves Teresa Nobre de Carvalho1 University of Lisbon Abstract: Cloves have been prized since Ancient times for their agreeable smell and ther- apeutic properties. With the publication of Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas he Cousas Mediçinais da Índia (Goa, 1563), Garcia de Orta (c. 1500-1568) presented the first modern monographic study of cloves. In this analysis I wish to clarify what kind of information about Asian natural resources (cloves in particular) circulated in Europe, from Antiquity until the sixteenth century, and how the Portuguese medical treatises, led to the emer- gence of an innovative botanical discourse about tropical plants in Early Modern Europe. Keywords: cloves; Syzygium aromaticum L; Garcia de Orta; Early Modern Botany; Asian drugs and spices. Imagens da especiaria que circunavegou o globo O contributo dos colóquios dos simples de Garcia de Orta (Goa, 1563) à construção de um conhecimento totalmente novo sobre o cravo-da-índia. Resumo: O cravo-da-Índia foi estimado desde os tempos Antigos por seu cheiro agradável e propriedades terapêuticas. Com a publicação dos Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas, e Cousas Mediçinais da Índia (Goa, 1563), Garcia de Orta (1500-1568) apresentou o primeiro estudo monográfico moderno sobre tal especiaria. Nesta análise, gostaria de esclarecer que tipo de informação sobre os recursos naturais asiáticos (especiarias em particular) circulou na Eu- ropa, da Antiguidade até o século xvi, e como os tratados médicos portugueses levaram ao surgimento de um inovador discurso botânico sobre plantas tropicais na Europa moderna. -

Local Trade Networks in Maluku in the 16Th, 17Th and 18Th Centuries

CAKALELEVOL. 2, :-f0. 2 (1991), PP. LOCAL TRADE NETWORKS IN MALUKU IN THE 16TH, 17TH, AND 18TH CENTURIES LEONARD Y. ANDAYA U:-fIVERSITY OF From an outsider's viewpoint, the diversity of language and ethnic groups scattered through numerous small and often inaccessible islands in Maluku might appear to be a major deterrent to economic contact between communities. But it was because these groups lived on small islands or in forested larger islands with limited arable land that trade with their neighbors was an economic necessity Distrust of strangers was often overcome through marriage or trade partnerships. However, the most . effective justification for cooperation among groups in Maluku was adherence to common origin myths which established familial links with societies as far west as Butung and as far east as the Papuan islands. I The records of the Dutch East India Company housed in the State Archives in The Hague offer a useful glimpse of the operation of local trading networks in Maluku. Although concerned principally with their own economic activities in the area, the Dutch found it necessary to understand something of the nature of Indigenous exchange relationships. The information, however, never formed the basis for a report, but is scattered in various documents in the form of observations or personal experiences of Dutch officials. From these pieces of information it is possible to reconstruct some of the complexity of the exchange in MaJuku in these centuries and to observe the dynamism of local groups in adapting to new economic developments in the area. In addition to the Malukans, there were two foreign groups who were essential to the successful integration of the local trade networks: the and the Chinese. -

Adjustment of Jepara Industrial Furniture Business for Business Stability

Adjustment of Jepara Industrial Furniture Business for Business Stability Angelina Ika Rahutami, Widuri Kurniasari, Chatarina Yekti Prawihatmi College of Economics and Business, Soegijapranata Catholic University, Semarang, Indonesia ____________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract Furniture industry in Jepara is a strategic industry both for local and national economy. Furniture industry in Jepara is uniquely known for its carving. This research is aimed to conduct a mapping of furniture industry condition in Jepara. In addition, this research also conducts an investigation of how furniture industry in Jepara performs its online and external business adjustment.The research has been conducted in Jepara district, Central Java. The sample collected from micro small medium enterprises (MSMEs) in the furniture field. The research used primary data collected through questionnaires and in-depth interviews. The key informants of this research are policy makers , such as Head of the Industrial Board, Head of the Trade Board, and Head of Cooperative and MSMEs, Head of furniture association at the provincial level of Central Java and Jepara District, and 5 players of furniture industry in Jepara. The variables observed in this study are: business competition, management priority, performamce and innovation. In facing globalization, furniture industry in Jepara conducts some adjustments internally and externally. All industry players attempt to behave adaptively toward business development and compettion by doing design innovation continuously. Furniture industry businessmen also motivate their employees to be creative and innovative. Externally, local government contantly supports the existence and competitiveness of the industry by providing facility for promotion and exhibition both national and international level. Business strategies that can be applied are improving product durability and design variation. -

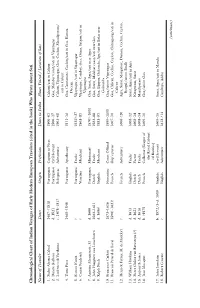

Who W Rote About Sati Name Of

Chronological Chart of Indian Voyages of Early Modern European Travelers (cited in the book) Who Wrote about Sati Name of Traveler Dates Origin Profession Dates in India Places Visited / Location of Sati 1. Pedro Alvares Cabral 1467–?1518 Portuguese Captain of Fleet 1500–01 Calicut/sati in Calicut 2. Duarte Barbosa d. 1521 Portuguese Civil Servant 1500–17 Goa, Malabar Coast/sati in Vijaynagar 3. Ludovico di Varthema c. 1475–1517 Bolognese Adventurer 1503–08 Calicut, Vijaynagar, Goa, Cochin, Masulipatam/ sati in Calicut 4. Tome Pires 1468–1540 Portuguese Apothecary 1511–16 Goa, Cannanore, Cochin/sati in Goa, Kanara, Deccan 5. Fernao Nuniz ? Portuguese Trader 1535?–37 Vijaynagar/sati in Vijaynagar 6. Caesar Frederick ? Venetian Merchant 1563–81 Vijaynagar, Cambay, Goa, Orissa, Satgan/sati in Vijaynagar 7. Antoine Monserrate, SJ d. 1600 Portuguese Missionary 1570?–1600 Goa, Surat, Agra/sati near Agra 8. John Huyghen van Linschoten 1563–1611 Dutch Trader 1583–88 Goa, Surat, Malabar coast/sati near Goa 9. Ralph Fitch d. 1606? English Merchant 1583–91 Goa, Bijapur, Golconda, Agr/sati in Bidar near Golconda 10. Francesco Carletti 1573–1636 Florentine Court Official 1599–1601 Goa/sati in Vijaynagar 11. Francois Pyrard de Laval 1590?–1621? French Ship’s purser 1607–10 Goa, Calicut, Cochin, Ceylon, Chittagong/sati in Calicut 12. Henri de Feynes, M. de Montfort ? French Adventurer 1608–?20 Agra, Surat, Mangalore, Daman, Cochin, Ceylon, Bengal/sati in Sindh 13. William Hawkins d. 1613 English Trader 1608–12 Surat, Agra/sati in Agra 14. Pieter Gielisz van Ravesteyn (?) d. 1621 Dutch Factor 1608–14 Nizapatam, Surat 15. -

From Paradise Lost to Promised Land: Christianity and the Rise of West

School of History & Politics & Centre for Asia Pacific Social Transformation Studies (CAPSTRANS) University of Wollongong From Paradise Lost to Promised Land Christianity and the Rise of West Papuan Nationalism Susanna Grazia Rizzo A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) of the University of Wollongong 2004 “Religion (…) constitutes the universal horizon and foundation of the nation’s existence. It is in terms of religion that a nation defines what it considers to be true”. G. W. F. Hegel, Lectures on the of Philosophy of World History. Abstract In 1953 Aarne Koskinen’s book, The Missionary Influence as a Political Factor in the Pacific Islands, appeared on the shelves of the academic world, adding further fuel to the longstanding debate in anthropological and historical studies regarding the role and effects of missionary activity in colonial settings. Koskinen’s finding supported the general view amongst anthropologists and historians that missionary activity had a negative impact on non-Western populations, wiping away their cultural templates and disrupting their socio-economic and political systems. This attitude towards mission activity assumes that the contemporary non-Western world is the product of the ‘West’, and that what the ‘Rest’ believes and how it lives, its social, economic and political systems, as well as its values and beliefs, have derived from or have been implanted by the ‘West’. This postulate has led to the denial of the agency of non-Western or colonial people, deeming them as ‘history-less’ and ‘nation-less’: as an entity devoid of identity. But is this postulate true? Have the non-Western populations really been passive recipients of Western commodities, ideas and values? This dissertation examines the role that Christianity, the ideology of the West, the religion whose values underlies the semantics and structures of modernisation, has played in the genesis and rise of West Papuan nationalism. -

John FT Keane's Late Nineteenth Century Ḥajj by Nicole J. Crisp BA

Out of Obscurity: John F. T. Keane’s Late Nineteenth Century Ḥajj by Nicole J. Crisp B.A. in History, May 2014, University of Nevada, Las Vegas B.A. in Anthropology, May 2014, University of Nevada, Las Vegas A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts May 21, 2017 Thesis directed by Dina Rizk Khoury Professor of History © Copyright 2017 by Nicole J. Crisp All rights reserved ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professors Khoury and Blecher specifically for guiding me through the journey of writing this thesis as well as the rest of the George Washington University’s History Department whose faculty, students, and staff have created an unforgettable learning experience over the past three years. Further, I would like to thank my co-workers, both in College Park, Maryland, and Washington, D.C., some of whom have become like family to me and helped me through thick and thin. I would also be remiss if I were not to thank my best friend, Danielle Romero, who mentioned me in the acknowledgements page of her thesis so I effectively must mention her here and quote a line from series that got me through the end of this thesis, “Bang.” I would also like to express my gratitude to my Aunt Joy Harris who has been a constant fountain of encouragement. Finally, I would like to thank my parents, Larry and Dianne, to whom this thesis is dedicated. -

* Omslag Dutch Ships in Tropical:DEF 18-08-09 13:30 Pagina 1

* omslag Dutch Ships in Tropical:DEF 18-08-09 13:30 Pagina 1 dutch ships in tropical waters robert parthesius The end of the 16th century saw Dutch expansion in Asia, as the Dutch East India Company (the VOC) was fast becoming an Asian power, both political and economic. By 1669, the VOC was the richest private company the world had ever seen. This landmark study looks at perhaps the most important tool in the Company’ trading – its ships. In order to reconstruct the complete shipping activities of the VOC, the author created a unique database of the ships’ movements, including frigates and other, hitherto ignored, smaller vessels. Parthesius’s research into the routes and the types of ships in the service of the VOC proves that it was precisely the wide range of types and sizes of vessels that gave the Company the ability to sail – and continue its profitable trade – the year round. Furthermore, it appears that the VOC commanded at least twice the number of ships than earlier historians have ascertained. Combining the best of maritime and social history, this book will change our understanding of the commercial dynamics of the most successful economic organization of the period. robert parthesius Robert Parthesius is a naval historian and director of the Centre for International Heritage Activities in Leiden. dutch ships in amsterdam tropical waters studies in the dutch golden age The Development of 978 90 5356 517 9 the Dutch East India Company (voc) Amsterdam University Press Shipping Network in Asia www.aup.nl dissertation 1595-1660 Amsterdam University Press Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters The development of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) shipping network in Asia - Robert Parthesius Founded in as part of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Amsterdam (UvA), the Amsterdam Centre for the Study of the Golden Age (Amsterdams Centrum voor de Studie van de Gouden Eeuw) aims to promote the history and culture of the Dutch Republic during the ‘long’ seventeenth century (c.