The Depictions of the Spice That Circumnavigated the Globe. the Contribution of Garcia De Orta's Colóquios Dos Simples (Goa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Abode of Islam Under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms Among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar

JIOWSJournal of Indian Ocean World Studies An Abode of Islam under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar Mahmood Kooria To cite this article: Kooria, Mahmood. “An Abode of Islam Under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar.” Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies, 1 (2017), pp. 89-109. More information about the Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies can be found at: jiows.mcgill.ca © Mahmood Kooria. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Li- cense CC BY NC SA, which permits users to share, use, and remix the material provide they give proper attribu- tion, the use is non-commercial, and any remixes/transformations of the work are shared under the same license as the original. Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies, 1 (2017), pp. 89-109. © Mahmood Kooria, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 | 89 An Abode of Islam under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar Mahmood Kooria* Leiden University, Netherlands ABSTRACT When Vasco da Gama asked the Zamorin (ruler) of Calicut to expel from his domains all Muslims hailing from Cairo and the Red Sea, the Zamorin rejected it, saying that they were living in his kingdom “as natives, not foreigners.” This was a marker of reciprocal understanding between Muslims and Zamorins. When war broke out with the Portuguese, Muslim intellectuals in the region wrote treatises and delivered sermons in order to mobilize their community in support of the Zamorins. -

14Th Sakyadhita International Conference for Buddhist Women

14th Sakyadhita International Conference for Buddhist Women http://www.sakyadhita.org/conferences/14th-si-con/14th-si-con-abstracts... Home Conferences Act Locally Resources Contact Online Resources 14th Sakyadhita International Conference June 23-30, 2015 "Compass ion & Social Justice" Yogyakarta, Indonesia Conference Program* *Please note this program is subject to change. - Bahasa Indonesa Language Program - English Language Program - French Language Program - German Language Program Register for the 14th SI Conference Click here to register for the 14th Sakyadhita International Conference on Buddhist Women. 14th SI Conference Brochure Conference Abstracts: Click here to download a brochure for the 2015 SI Conference on Buddhist Women. Additional "Compassion and Social Justice" languages below: 14th Sakyadhita International Conference on Buddhist Women - Bahasa Indonesia Language Brochure Yogyakarta, Indonesia - Simplified Chinese Language Brochure June 23-30, 2015 - Traditional Chinese Language Brochure - English Language Brochure - French Language Brochure A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z - German Language Brochure - Japanese Language Brochure - Korean Language Brochure Read All Abstracts - Russian Language Brochure - Spanish Language Brochure PDF of this page - Tibetan Language Brochure Conference & Tour Details Click here for more information on the 14th SI A Conference, and tour details. Yogyakarta, Indonesia Ayya Santini Establishing the Bhikkhuni Sangha in -

A Construçao Do Conhecimento

MAPAS E ICONOGRAFIA DOS SÉCS. XVI E XVII 1369 [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] Apêndices A armada de António de Abreu reconhece as ilhas de Amboino e Banda, 1511 Francisco Serrão reconhece Ternate (Molucas do Norte), 1511 Primeiras missões portuguesas ao Sião e a Pegu, 1. Cronologias 1511-1512 Jorge Álvares atinge o estuário do “rio das Pérolas” a bordo de um junco chinês, Junho I. Cronologia essencial da corrida de 1513 dos europeus para o Extremo Vasco Núñez de Balboa chega ao Oceano Oriente, 1474-1641 Pacífico, Setembro de 1513 As acções associadas de modo directo à Os portugueses reconhecem as costas do China a sombreado. Guangdong, 1514 Afonso de Albuquerque impõe a soberania Paolo Toscanelli propõe a Portugal plano para portuguesa em Ormuz e domina o Golfo atingir o Japão e a China pelo Ocidente, 1574 Pérsico, 1515 Diogo Cão navega para além do cabo de Santa Os portugueses começam a frequentar Solor e Maria (13º 23’ lat. S) e crê encontrar-se às Timor, 1515 portas do Índico, 1482-1484 Missão de Fernão Peres de Andrade a Pêro da Covilhã parte para a Índia via Cantão, levando a embaixada de Tomé Pires Alexandria para saber das rotas e locais de à China, 1517 comércio do Índico, 1487 Fracasso da embaixada de Tomé Pires; os Bartolomeu Dias dobra o cabo da Boa portugueses são proibidos de frequentar os Esperança, 1488 portos chineses; estabelecimento do comércio Cristóvão Colombo atinge as Antilhas e crê luso ilícito no Fujian e Zhejiang, 1521 encontrar-se nos confins -

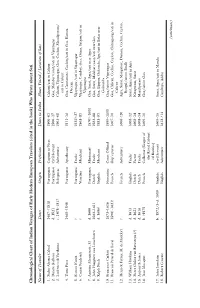

Who W Rote About Sati Name Of

Chronological Chart of Indian Voyages of Early Modern European Travelers (cited in the book) Who Wrote about Sati Name of Traveler Dates Origin Profession Dates in India Places Visited / Location of Sati 1. Pedro Alvares Cabral 1467–?1518 Portuguese Captain of Fleet 1500–01 Calicut/sati in Calicut 2. Duarte Barbosa d. 1521 Portuguese Civil Servant 1500–17 Goa, Malabar Coast/sati in Vijaynagar 3. Ludovico di Varthema c. 1475–1517 Bolognese Adventurer 1503–08 Calicut, Vijaynagar, Goa, Cochin, Masulipatam/ sati in Calicut 4. Tome Pires 1468–1540 Portuguese Apothecary 1511–16 Goa, Cannanore, Cochin/sati in Goa, Kanara, Deccan 5. Fernao Nuniz ? Portuguese Trader 1535?–37 Vijaynagar/sati in Vijaynagar 6. Caesar Frederick ? Venetian Merchant 1563–81 Vijaynagar, Cambay, Goa, Orissa, Satgan/sati in Vijaynagar 7. Antoine Monserrate, SJ d. 1600 Portuguese Missionary 1570?–1600 Goa, Surat, Agra/sati near Agra 8. John Huyghen van Linschoten 1563–1611 Dutch Trader 1583–88 Goa, Surat, Malabar coast/sati near Goa 9. Ralph Fitch d. 1606? English Merchant 1583–91 Goa, Bijapur, Golconda, Agr/sati in Bidar near Golconda 10. Francesco Carletti 1573–1636 Florentine Court Official 1599–1601 Goa/sati in Vijaynagar 11. Francois Pyrard de Laval 1590?–1621? French Ship’s purser 1607–10 Goa, Calicut, Cochin, Ceylon, Chittagong/sati in Calicut 12. Henri de Feynes, M. de Montfort ? French Adventurer 1608–?20 Agra, Surat, Mangalore, Daman, Cochin, Ceylon, Bengal/sati in Sindh 13. William Hawkins d. 1613 English Trader 1608–12 Surat, Agra/sati in Agra 14. Pieter Gielisz van Ravesteyn (?) d. 1621 Dutch Factor 1608–14 Nizapatam, Surat 15. -

The Malay World in the Medieval European Imagination: the Case of Ludovico Di Varthema’S Travel Accounts on the Malay World

THE MALAY WORLD IN THE MEDIEVAL EUROPEAN IMAGINATION: THE CASE OF LUDOVICO DI VARTHEMA’S TRAVEL ACCOUNTS ON THE MALAY WORLD BY ZULKIFLI BIN ISHAK A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Human Sciences (History and Civilization) Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences International Islamic University Malaysia August 2009 ABSTRACT Throughout the medieval period of the European history, images of the Malay World were constantly portrayed in the accounts of the medieval European travelers. These descriptions which are predominantly concerned with the people, geography and th traditions of the region were recorded to have existed as early as the 13 century. In th the first quarter of the 16 century, a Bolognese, Ludovico di Varthema produced descriptions of his travels which includes his journey to the Malay World between the years 1504 and 1505 C.E. His travel experience was first published in Italy in 1510 C.E. This study analyses the contents of the medieval European travelers’ accounts on the Malay World; with particular reference to Varthema’s travel accounts entitled Itinerario. It focuses on the factors that reflected Varthema’s apprehension in constructing pictures of the society and civilization of the Malay World. Finally, this study argues that the medieval European travelers’ accounts that were produced in constructing the images of the Malay World were written in accordance to the standard cliché of the medieval travel writings that was practiced in the course of the medieval period where it involved the influences of the classical Greco-Roman and the biblical traditions. -

John FT Keane's Late Nineteenth Century Ḥajj by Nicole J. Crisp BA

Out of Obscurity: John F. T. Keane’s Late Nineteenth Century Ḥajj by Nicole J. Crisp B.A. in History, May 2014, University of Nevada, Las Vegas B.A. in Anthropology, May 2014, University of Nevada, Las Vegas A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts May 21, 2017 Thesis directed by Dina Rizk Khoury Professor of History © Copyright 2017 by Nicole J. Crisp All rights reserved ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professors Khoury and Blecher specifically for guiding me through the journey of writing this thesis as well as the rest of the George Washington University’s History Department whose faculty, students, and staff have created an unforgettable learning experience over the past three years. Further, I would like to thank my co-workers, both in College Park, Maryland, and Washington, D.C., some of whom have become like family to me and helped me through thick and thin. I would also be remiss if I were not to thank my best friend, Danielle Romero, who mentioned me in the acknowledgements page of her thesis so I effectively must mention her here and quote a line from series that got me through the end of this thesis, “Bang.” I would also like to express my gratitude to my Aunt Joy Harris who has been a constant fountain of encouragement. Finally, I would like to thank my parents, Larry and Dianne, to whom this thesis is dedicated. -

List of Works Cited

List of Works Cited This is a simple list of the works quoted or mentioned in the foregoing text or notes. Where a work not originally written in English has been translated, the best available English edition is the one listed; otherwise, the best available edition in the original language. I Francesco Balducci Pegolotti, ed. A. Evans: La practica della merca tura, Cambridge, Mass., 1936. H. Yule, ed.: Cathay and the Way Thither, 3 vols., znd edn, London, 1913-16. Marco Polo, ed. A. C. Moule and Paul Pelliot: The Description of the World, 2 vols., London, 1938. Pierre d'Ailly, trans. Edwin F. Keever: Imago Mundi, Wilmington N.C., 1948. Joannes de Sacro Bosco (John of Holywood), ed. Joaquin Bensaude: "Tractado da sphera do mundo," in Regimento do astrolabio e do quadrante, Munich, 1914. (Facsimile edition of the unique Munich copy of the earliest printed navigation manual.) Claudius Ptolemaeus, ed. and trans. E. L. Stevenson: The Geography of Claudius Ptolemy, New York, 1932. Roger Bacon, ed. and trans. Robert B. Burke: Opus majus, Oxford, 1928. Ibn Battuta, ed. and trans. H. A. R. Gibb: The Travels of Ibn Battuta, vols. I and II, Cambridge, 1958-62. II Malcolm Letts, ed. and trans.: Mandeville's Travels, Texts and Transla tions, 2 vols., London, 1953. ]66 LIST OF WORKS CITED R. H. Major, ed.: India in the Fifteenth Century, London, I857: "The travels of Nicolo de' Conti ... as related by Poggio Bracciolini, in his work entitled Historia de varietate fortunae, Lib IV." III Gomes Eannes de Azurara, ed. Charles Raymond Beazley and Edgar Prestage. -

The Role of Charts in Islamic Navigation in the Indian Ocean

13 · The Role of Charts in Islamic Navigation in the Indian Ocean GERALD R. TIBBETTS The existence of indigenous navigational charts of the voyage.7 Barros wrote in the 1540s and could have read Indian Ocean is suggested by several early European Varthema's work, which was in many editions by that sources, the earliest of which is the brief mention of date, including an edition in Spanish published in Seville mariners' charts by Marco Polo. First, in connection with in 1520. There are other occasions when Barros seems Ceylon Polo mentions "la mapemondi des mariner de cel to have incorporated later materials into his version of mer,"! a reference that can only refer to a nautical map the earlier Portuguese accounts of the Indian Ocean, so of some sort. Second, in connection with the Indian west some doubt is cast on the accuracy of his statement. coast he refers to "Ie conpas e la scriture de sajes rnar In 1512 another possible local chart is mentioned by iner."2 This first word has been translated as "charts," Afonso de Albuquerque in a letter to the Portuguese king and strangely enough it is the very word (al-qunbii~) used Manuel. He reports that he had seen a large chart belong by Abmad ibn Majid (fl. A.D. 1460-1500) in connection ing to a pilot on which Brazil, the Indian Ocean, and the with portolan charts.3 Far East were shown. This chart can only have been very The other sources are Portuguese and come from the sketchy, for the Portuguese pilot Francisco Rodrigues period when that country had reached these parts. -

Model Test Paper-1

MODEL TEST PAPER-1 No. of Questions: 120 Time: 2 hours Codes: I II III IV (a) A B C D Instructions: (b) C A B D (c) A C D B (A) All questions carry equal marks (d) C A D B (B) Do not waste your time on any particular question 4. Where do we find the three phases, viz. Paleolithic, (C) Mark your answer clearly and if you want to change Mesolithic and Neolithic Cultures in sequence? your answer, erase your previous answer completely. (a) Kashmir Valley (b) Godavari Valley (c) Belan Valley (d) Krishna Valley 1. Pot-making, a technique of great significance 5. Excellent cave paintings of Mesolithic Age are found in human history, appeared first in a few areas at: during: (a) Bhimbetka (b) Atranjikhera (a) Early Stone Age (b) Middle Stone Age (c) Mahisadal (d) Barudih (c) Upper Stone Age (d) Late Stone Age 6. In the upper Ganga valley iron is first found associated 2. Which one of the following pairs of Palaeolithic sites with and areas is not correct? (a) Black-and-Red Ware (a) Didwana—Western Rajasthan (b) Ochre Coloured Ware (b) Sanganakallu—Karnataka (c) Painted Grey Ware (c) Uttarabaini—Jammu (d) Northern Black Polished Ware (d) Riwat—Pakistani Punjab 7. Teri sites, associated with dunes of reddened sand, 3. Match List I with List II and select the answer from are found in: the codes given below the lists: (a) Assam (b) Madhya Pradesh List I List II (c) Tamil Nadu (d) Andhra Pradesh Chalcolithic Cultures Type Sites 8. -

Fifteenth-Century Italian Travel Writings on India

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935) Indexed by Web of Science, Scopus, DOAJ, ERIHPLUS Vol. 13, No. 1, January-March, 2021. 1-12 Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V13/n1/v13n133.pdf DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v13n1.33 Published on March 28, 2021 India nel quattrocento: Fifteenth-Century Italian Travel Writings on India Jitamanyu Das Doctoral Candidate (JRF), Department of English, Jadavpur University, ORCID: 0000-0001- 5845-8098, [email protected], Abstract Fifteenth-century Italian travel narratives on India by Nicolò dei Conti and Gerolamo di Santo Stefano present a detailed account of the India they visited, following the narrative tradition of the Italian Marco Polo. These narratives of the Renaissance were published as descriptive authorial texts of travellers to the East. Their importance was due to the authors’ detailed first-hand experiences of the societies and cultures that they encountered, as well as the various trade centres of the period. These narratives were utilised by merchants, explorers, and Jesuits for a variety of purposes. The narratives of Nicolò dei Conti and Gerolamo di Santo Stefano thus became indispensable tools that were later distorted through numerous translations to suit the politics of Orientalism for the emerging colonial enterprises. In my paper, I have attempted a re-reading of the particular texts to identify how Italy saw India, while illustrating through their history of publication the transformation that these narratives underwent later in order to objectify India in the West through the lens of Orientalism in their manner of representation. Keywords: India, Italian Travel Writing, Orientalism, Renaissance, Translation The study of Western approaches towards India and the Indian Ocean Region has gone through a noteworthy shift in the last few decades. -

Repor T Resumes

REPOR TRESUMES ED 017 908 48 AL 000 990 CHAPTERS IN INDIAN CIVILIZATION--A HANDBOOK OF READINGS TO ACCOMPANY THE CIVILIZATION OF INDIA SYLLABUS. VOLUME II, BRITISH AND MODERN INDIA. BY- ELDER, JOSEPH W., ED. WISCONSIN UNIV., MADISON, DEPT. OF INDIAN STUDIES REPORT NUMBER BR-6-2512 PUB DATE JUN 67 CONTRACT OEC-3-6-062512-1744 EDRS PRICE MF-$1.25 HC-$12.04 299P. DESCRIPTORS- *INDIANS, *CULTURE, *AREA STUDIES, MASS MEDIA, *LANGUAGE AND AREA CENTERS, LITERATURE, LANGUAGE CLASSIFICATION, INDO EUROPEAN LANGUAGES, DRAMA, MUSIC, SOCIOCULTURAL PATTERNS, INDIA, THIS VOLUME IS THE COMPANION TO "VOLUME II CLASSICAL AND MEDIEVAL INDIA," AND IS DESIGNED TO ACCOMPANY COURSES DEALING WITH INDIA, PARTICULARLY THOSE COURSES USING THE "CIVILIZATION OF INDIA SYLLABUS"(BY THE SAME AUTHOR AND PUBLISHERS, 1965). VOLUME II CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING SELECTIONS--(/) "INDIA AND WESTERN INTELLECTUALS," BY JOSEPH W. ELDER,(2) "DEVELOPMENT AND REACH OF MASS MEDIA," BY K.E. EAPEN, (3) "DANCE, DANCE-DRAMA, AND MUSIC," BY CLIFF R. JONES AND ROBERT E. BROWN,(4) "MODERN INDIAN LITERATURE," BY M.G. KRISHNAMURTHI, (5) "LANGUAGE IDENTITY--AN INTRODUCTION TO INDIA'S LANGUAGE PROBLEMS," BY WILLIAM C. MCCORMACK, (6) "THE STUDY OF CIVILIZATIONS," BY JOSEPH W. ELDER, AND(7) "THE PEOPLES OF INDIA," BY ROBERT J. AND BEATRICE D. MILLER. THESE MATERIALS ARE WRITTEN IN ENGLISH AND ARE PUBLISHED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF INDIAN STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN, MADISON, WISCONSIN 53706. (AMM) 11116ro., F Bk.--. G 2S12 Ye- CHAPTERS IN INDIAN CIVILIZATION JOSEPH W ELDER Editor VOLUME I I BRITISH AND MODERN PERIOD U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

Built on Diversity: Statehood in Medieval Somaliland (12Th-16Th

Built on diversity: Statehood in Medieval Somaliland (12th-16th centuries AD) Jorge de Torres Rodriguez A 06 Built on diversity: Statehood in Medieval Somaliland (12th-16th centuries AD) Construido sobre la diversidad: las estructuras estatales medievales de Somalilandia (siglos XII a XVI) Jorge de Torres Rodriguez Resumen Este artículo pretende ofrecer una visión general de la arqueología medieval mu- sulmana en el Cuerno de África, poniendo énfasis en el papel de los estados me- dievales que durante más de tres siglos fueron capaces de integrar poblaciones con creencias, estilos de vida, lenguas y etnias muy diferentes. El estudio combi- na fuentes históricas y arqueológicas para analizar el caso específico del oeste de Somalilandia, una región en la que grupos sedentarios y nómadas con culturas ma- teriales muy diferentes convivieron durante siglos. A través del análisis de las rela- ciones entre estos dos grupos se plantea una propuesta sobre el modo en que los estados musulmanes fueron capaces de proporcionar unas marco estable y cohesio- nado para la región durante toda la Edad Media. Palabras clave: Cuerno de África, Edad Media, Estados, Islam, Arqueología medie- val, nómadas Abstract This article presents an overview of the current situation of the medieval Islamic archaeology of the Horn of Africa, paying especial attention to the role of the me- dieval states that for more than three centuries were able to integrate peoples with very different beliefs, lifestyles, languages and ethnicities. The study combines his- torical and archaeological sources to analyze a specific case in western Somaliland, a region where nomads and urban dwellers –two groups with very different material cultures- lived together for centuries.