Myths, Militias and the Destruction of Loi Sam Sip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

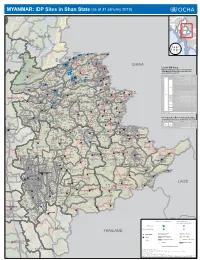

China Thailand Laos

MYANMAR IDP Sites in Shan State As of 30 June 2021 BHUTAN INDIA CHINA BANGLADESH MYANMAR Nay Pyi Taw LAOS KACHIN THAILAND CHINA List of IDP Sites In nothern Shan No. State Township IDP Site IDPs 1 Hseni Nam Sa Larp 267 2 Hsipaw Man Kaung/Naung Ti Kyar Village 120 3 Bang Yang Hka (Mung Ji Pa) 162 4 Galeng (Palaung) & Kone Khem 525 5 Galeng Zup Awng ward 5 RC 134 6 Hu Hku & Ho Hko 131 SAGAING Man Yin 7 Kutkai downtown (KBC Church) 245 Man Pying Loi Jon 8 Kutkai downtown (KBC Church-2) 155 Man Nar Pu Wan Chin Mu Lin Huong Aik 9 Mai Yu Lay New (Ta'ang) 398 Yi Hku La Shat Lum In 22 Nam Har 10 Kutkai Man Loi 84 Ngar Oe Shwe Kyaung Kone 11 Mine Yu Lay village ( Old) 264 Muse Nam Kut Char Lu Keng Aik Hpan 12 Mung Hawm 170 Nawng Mo Nam Kat Ho Pawt Man Hin 13 Nam Hpak Ka Mare 250 35 ☇ Konkyan 14 Nam Hpak Ka Ta'ang ( Aung Tha Pyay) 164 Chaung Wa 33 Wein Hpai Man Jat Shwe Ku Keng Kun Taw Pang Gum Nam Ngu Muse Man Mei ☇ Man Ton 15 New Pang Ku 688 Long Gam 36 Man Sum 16 Northern Pan Law 224 Thar Pyauk ☇ 34 Namhkan Lu Swe ☇ 26 Kyu Pat 12 KonkyanTar Shan Loi Mun 17 Shan Zup Aung Camp 1,084 25 Man Set Au Myar Ton Bar 18 His Aw (Chyu Fan) 830 Yae Le Man Pwe Len Lai Shauk Lu Chan Laukkaing 27 Hsi Hsar 19 Shwe Sin (Ward 3) 170 24 Tee Ma Hsin Keng Pang Mawng Hsa Ka 20 Mandung - Jinghpaw 147 Pwe Za Meik Nar Hpai Nyo Chan Yin Kyint Htin (Yan Kyin Htin) Manton Man Pu 19 Khaw Taw 21 Mandung - RC 157 Aw Kar Shwe Htu 13 Nar Lel 18 22 Muse Hpai Kawng 803 Ho Maw 14 Pang Sa Lorp Man Tet Baing Bin Nam Hum Namhkan Ho Et Man KyuLaukkaing 23 Mong Wee Shan 307 Tun Yone Kyar Ti Len Man Sat Man Nar Tun Kaw 6 Man Aw Mone Hka 10 KutkaiNam Hu 24 Nam Hkam - Nay Win Ni (Palawng) 402 Mabein Ton Kwar 23 War Sa Keng Hon Gyet Pin Kyein (Ywar Thit) Nawng Ae 25 Namhkan Nam Hkam (KBC Jaw Wang) 338 Si Ping Kaw Yi Man LongLaukkaing Man Kaw Ho Pang Hopong 9 16 Nar Ngu Pang Paw Long Htan (Tart Lon Htan) 26 Nam Hkam (KBC Jaw Wang) II 32 Ma Waw 11 Hko Tar Say Kaw Wein Mun 27 Nam Hkam Catholic Church ( St. -

BICAS Working Paper 14 Woods

Working 14 Paper CP maize contract farming in Shan State, Myanmar: A regional case of a place-based corporate agro-feed system Kevin Woods May 2015 1 CP maize contract farming in Shan State, Myanmar: A regional case of a place‐based corporate agro‐feed system by Kevin Woods Published by: BRICS Initiative for Critical Agrarian Studies (BICAS) in collaboration with: Universidade de Brasilia Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP) Campus Universitário Darcy Ribeiro Rua Quirino de Andrade, 215 Brasília – DF 70910‐900 São Paulo ‐ SP 01049010 Brazil Brazil Tel: +55 61 3107‐3300 Tel: +55‐11‐5627‐0233 E‐mail: [email protected] E‐mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.unb.br/ Website: www.unesp.br Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Transnational Institute Av. Paulo Gama, 110 ‐ Bairro Farroupilha PO Box 14656 Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul 1001 LD Amsterdam Brazil The Netherlands Tel: +55 51 3308‐3281 Tel: +31 20 662 66 08 Fax: +31 20 675 71 76 E‐mail: [email protected] E‐mail: [email protected] Website: www.ufrgs.br/ Website: www.tni.org Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS) International Institute of Social Studies University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17 P.O. Box 29776 Bellville 7535, Cape Town 2502 LT The Hague South Africa The Netherlands Tel: +27 21 959 3733 Fax: +27 21 959 3732 Tel: +31 70 426 0460 Fax: +31 70 426 079 E‐mail: [email protected] E‐mail: [email protected] Website: www.plaas.org.za Website: www.iss.nl College of Humanities and Development Studies Future Agricultures Consortium China Agricultural University Institute of Development Studies No. -

Burma Coup Watch

This publication is produced in cooperation with Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN), Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Progressive Voice (PV), US Campaign for Burma (USCB), and Women Peace Network (WPN). BN 2021/2031: 1 Mar 2021 BURMA COUP WATCH: URGENT ACTION REQUIRED TO PREVENT DESTABILIZING VIOLENCE A month after its 1 February 2021 coup, the military junta’s escalation of disproportionate violence and terror tactics, backed by deployment of notorious military units to repress peaceful demonstrations, underlines the urgent need for substantive international action to prevent massive, destabilizing violence. The junta’s refusal to receive UN diplomatic and CONTENTS human rights missions indicates a refusal to consider a peaceful resolution to the crisis and 2 Movement calls for action confrontation sparked by the coup. 2 Coup timeline 3 Illegal even under the 2008 In order to avert worse violence and create the Constitution space for dialogue and negotiations, the 4 Information warfare movement in Burma and their allies urge that: 5 Min Aung Hlaing’s promises o International Financial Institutions (IFIs) 6 Nationwide opposition immediately freeze existing loans, recall prior 6 CDM loans and reassess the post-coup situation; 7 CRPH o Foreign states and bodies enact targeted 7 Junta’s violent crackdown sanctions on the military (Tatmadaw), 8 Brutal LIDs deployed Tatmadaw-affiliated companies and partners, 9 Ongoing armed conflict including a global arms embargo; and 10 New laws, amendments threaten human rights o The UN Security Council immediately send a 11 International condemnation delegation to prevent further violence and 12 Economy destabilized ensure the situation is peacefully resolved. -

Myanmar Update February 2016 Report

STATUS OF HUMAN RIGHTS & SANCTIONS IN MYANMAR FEBRUARY 2016 REPORT Summary. This report reviews the February 2016 developments relating to human rights in Myanmar. Relatedly, it addresses the interchange between Myanmar’s reform efforts and the responses of the international community. I. Political Developments......................................................................................................2 A. Election-Related Developments and Power Transition...............................................2 B. Constitutional Reform....................................................................................................3 C. International and Community Sanctions......................................................................4 II. Civil and Political Rights...................................................................................................4 A. Press and Media Laws/Restrictions...............................................................................4 B. Official Corruption.........................................................................................................5 III. Political Prisoners..............................................................................................................5 IV. Governance and Rule of Law...........................................................................................6 V. Economic Development.....................................................................................................7 A. Land Seizures..................................................................................................................7 -

Analysis of Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Shan State and Strategic Options to Address Those

Analysis of drivers of deforestation and forest degradation in Shan State and strategic options to address those Author: Aung Aung Myint, National Consultant on analysis of drivers of deforestation and forest degradation in Shan State, ICIMOD-GIZ REDD+ project. [email protected]: +95 9420705116. Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Acknowledgement 2 Abbreviation and Acronyms 3 List of Figures 5 List of Tables 8 1. Introduction 9 1.1. Description of the assignment 12 1.2. Study area: brief description 12 1.3. Scope of the study 14 1.4. Objectives of the assignment 15 1.5. Expected outputs 15 2 Methodology 16 2.1. Data collection and analysis 16 2.1.1. Secondary data collection 16 2.1.2. Primary data collection 16 2.1.3. Spatial data analysis 17 2.1.4. Socio-economic data collection and analysis 19 2.2. Forest resources and their contributions in Myanmar and Shan State 27 2.3. Forest resources assessment 27 2.3.1. Major Forest Types 27 2.3.2. Forest cover change 29 2.3.3. National LULC categories and definitions 30 2.3.4. The NDVI composite maps for 2005 and 2015 43 2.3.5. Estimated magnitude of carbon emission due to deforestation and forest degradation (2005 to 2015) 47 2.3.6. Global Forest Watch were used to compare with international data 50 A. Identification of Deforestation and Forest Degradation 52 (i) Direct Drivers of deforestation and forest degradation 53 (ii) Indirect Drivers of deforestation and forest degradation 54 B. Determining co-relations between (i) Direst Drivers and (ii) Indirect Drivers of Deforestation and Forest -

Burma's Northern Shan State and Prospects for Peace

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE PEACEBRIEF234 United States Institute of Peace • www.usip.org • Tel. 202.457.1700 • @usip September 2017 DAVID SCOTT MATHIESON Burma’s Northern Shan State Email: [email protected] and Prospects for Peace Summary • Increased armed conflict between the Burmese Army and several ethnic armed organizations in northern Shan State threaten the nationwide peace process. • Thousands of civilians have been displaced, human rights violations have been perpetrated by all parties, and humanitarian assistance is being increasingly blocked by Burmese security forces. • Illicit economic activity—including extensive opium and heroin production as well as transport of amphetamine stimulants to China and to other parts of Burma—has helped fuel the conflict. • The role of China as interlocutor between the government, the military, and armed actors in the north has increased markedly in recent months. • Reconciliation will require diverse advocacy approaches on the part of international actors toward the civilian government, the Tatmadaw, ethnic armed groups, and civil society. To facili- tate a genuinely inclusive peace process, all parties need to be encouraged to expand dialogue and approach talks without precondition. Even as Burma has “transitioned from decades Introduction of civil war and military rule Even as Burma has transitioned—beginning in late 2010—from decades of civil war and military to greater democracy, long- rule to greater democracy, long-standing and widespread armed conflict has resumed between several ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) and the Burmese armed forces (Tatmadaw). Early in standing and widespread 2011, a 1994 ceasefire agreement broke down as relations deterioriated in the wake of the National armed conflict has resumed.” League for Democracy government’s refusal to permit Kachin political parties to participate in the elections that ended the era of military rule in the country. -

Sustainable Livelihoods Project Locations CHINA

S u s tt a ii n a b ll e L ii v e ll ii h o o d s P rr o jj e c tt L o c a tt ii o n s 96°E 98°E 100°E 102°E N N ° ° 4 4 2 2 \! INDIA CHINA ! Muse S.R.1 XSPK26: Increasing Food Security ! BMZ- Government Namkham \ and Promoting Licit Crop Production Laukkai of the Federal C H II N A Republic of Germany and Small Farmer Enterprise Development in Lao PDR and Myanmar Mabein Kutkai ! ! Kunlon! ! ! Hopang - Food shortages are estimated to affect 60-70% of sampled villages. Manton ! Theinne - 40% of the farmers do not have access to irrigation system. Momeik Namtu - Competition for land to plant food crops increases and poses a threat LAO PDR ! ! to food security Mongmao Namsang Lashio - 10-15% households moving back to opium poppy cultivation due to ! \! \! Food Insecurity. -Only 7 % of villages have access to health facilities; estimated 30 % NORTH SHAN of school children drop out school after 4 standards. Kyaukme ! - Only 18% of households has own production and enough food THAILAND ! Thibaw Tangyang Mongyai ! S.R.2 from their paddy land. Nawnghkio ! - Opium poppy cultivation remains attractive although as a ! cash crop ! N N ° ° 2 2 ! 2 2 ! ! Kye-thi Mongshu ! ! Makmang ! MANDALAY Mongkaing Monghkat Opium poppy cultivation density - 2010 SOUTH SHAN S.R.4 High Yaksawk ! MMRJ94, MMRJ95: 2007 Low Lai-hkia ! ! ! Mongpyin \!! Food Security Programme Ywa-ngan Kunhein Kyaing tong Mong-yawng ! \! ! for Myanmar No authorization area Pindaya European Union Opium poppy free area ! #0 Namsam EAST SHAN ! Monghpyat ! - !Food shortages are estimated to affect 75% of sampled villages. -

IDP Sites in Shan State (As of 31 January 2019)

MYANMAR: IDP Sites in Shan State (as of 31 January 2019) BHUTAN INDIA CHINA BANGLADESH Nay Pyi Taw LAOS KACHIN THAILAND Pang Hseng Man Kin (Kyu Koke) Monekoe SAGAING Kone Ma Na Maw Hteik 21 Nawt Ko Pu Wan Nam Kyar Mon Hon Tee Yi Hku Ngar Oe Nam War Manhlyoe 22 23 Nam Kut Char Lu Keng Aik Hpan Shwe Kyaung Kone U Yin Pu Nam Kat 36 (Manhero) Man Hin ☇ Muse Pa Kon War Yawng San Hsar Muse Konkyan Kun Taw 37 Man Mei ☇ Long Gam Man Ton ☇34 Tar Ku Ti Thea Chaung Namhkan 35 KonkyanTar Shan ☇ Man Set Kyu Pat 11 26 28 Au Myar Loi Mun Ton Bar 27 Yae Le Lin Lai 25 29 Hsi Hsar Hsin Keng Yan Long Keng CHINA Ho Nar Pang Mawng Long Htan Baing Law Se Long Nar Hpai Pwe Za Meik Khaw Taw HumLaukkaing Htin List of IDP Sites Aw Kar Pang Mu Shwe Htu Namhkan Kawng Hkam Nar Lel Se Kin 14 Bar Hpan Man Tet 15 Man Kyu Baing Bin Yan Bo (Lower) Nam Hum Tar Pong Ho Maw Ho Et Kyar Ti Lin Data provided by the Camp Coordination and Pang Hkan Hing Man Nar Hin Lai 4 Kutkai Nam Hu Man Sat Man Aw Mar Li Lint Ton Kwar 24 Camp Management (CCCM) Cluster based on Pin Kyein (Ywar Thit) Ho Pang 8 Hseng Hkawng Laukkaing Mabein 17 Man Hwei Si Ping Man Kaw Kaw Yi Hon Gyet Hopong Hpar Pyint Nar Ngu Long Htan update of 31 January 2018 Lawt Naw 9 Hko Tar Ma Waw 10 Tarmoenye Say Kaw Man Long Maw Han Loi Kan Ban Nwet Pying Kut Mabein Su Yway Namtit No. -

Myanmar Opium Survey 2019 Cultivation, Production and Implications

COVER MYANMAR OPIUM SURVEY 2019 CULTIVATION, PRODUCTION AND IMPLICATIONS DRAFT 2020-01-27 JANUARY 2020 In Southeast Asia, UNODC supports Member States to develop and implement evidence- based rule of law, drug control and related criminal justice responses through the Regional Programme 2014-2021 and aligned country programmes including the Myanmar Country Programme 2014-2021. This study is connected to the Mekong MOU on Drug Control which UNODC actively supports through the Regional Programme, including the commitment to develop data and evidence as the basis for countries of the Mekong region to respond to challenges of drug production, trafficking and use. UNODC’s Research and Trend Analysis Branch promotes and supports the development and implementation of surveys globally, including through its Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme (ICMP). The implementation of Myanmar opium survey was made possible thanks to the financial support of the Governments of Japan and the United States of America. UNODC Regional Office for Southeast Asia and the Pacific Telephone: +6622882100 Fax: +6622812129 Email: unodc‐[email protected] Website: www.unodc.org/southeastasiaandpacific Twitter: @UNODC_SEAP The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNODC concerning the legal status of any country, territory or city, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................... -

Safe Drinking Water in Myanmar the Republic of the Union of Myanmar

Safe Drinking Water in Myanmar The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Total land area 676,577sq.km Population : 58.4 M Rural/Urban : 70/30 Religion : Buddhism, Islam, Christians, 7 States & 7 Regions, Hindus 330 townships, The neighboring : 64,917 villages. Bangladesh, China, India, Laos, Thailand DRD • Policy:: – To Improve Socio-economic life of Rural Populace. • Tasks:: – Provision of Rural Save Drinking Water – Undertake work of Rural Sanitation Main Sources in Myanmar • Central dry zone Ground Water • Delta Surface Water, (ponds and shallow wells) • High Lands Spring, Ground Water Provision of Rural Safe Drinking Water Ten year plan from 2000-2001 to 2010-2011 1 0 Years Plan Completed Completed States / Regions Target Villages Activities Sagaing 2454 2560 3930 Magway 1469 1588 2706 Mandalay 4119 4359 7001 Other States/Regions 15183 16503 23907 Grand Total 23225 25010 37544 Source: DRD Donor No. State/ Region Village Tube Well 1 Sagaing 543 743 2 Magway 332 498 3 Mandalay 637 878 Total 1512 2119 878 Mandalay 637 498 Magway Tube Well 332 Village 743 Sagaing 543 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 1000 Rural Water Supplies by Local Donation UNDP ICDP Water Supply • UNDP contributed usd 77.36 million in 17 townships • Rain water harvesting tanks 112559 • Drilling shallow and hand dug wells 1061 • Construction of small dams 32 UNICEF • From 1997-98 to 2000-2001 supplied material for 3562 Water Supply Systems in 17 region/states • From 2001-2005 Government, UNICEF and Community jointly implemented – Shallow Tube Well 924 Nos – Deep Tube -

Myanmar: Ethnic Politics and the 2020 General Election

MYANMAR POLICY BRIEFING | 23 | September 2020 Myanmar: Ethnic Politics and the 2020 General Election KEY POINTS • The 2020 general election is scheduled to take place at a critical moment in Myanmar’s transition from half a century under military rule. The advent of the National League for Democracy to government office in March 2016 was greeted by all the country’s peoples as the opportunity to bring about real change. But since this time, the ethnic peace process has faltered, constitutional reform has not started, and conflict has escalated in several parts of the country, becoming emergencies of grave international concern. • Covid-19 represents a new – and serious – challenge to the conduct of free and fair elections. Postponements cannot be ruled out. But the spread of the pandemic is not expected to have a significant impact on the election outcome as long as it goes ahead within constitutionally-appointed times. The NLD is still widely predicted to win, albeit on reduced scale. Questions, however, will remain about the credibility of the polls during a time of unprecedented restrictions and health crisis. • There are three main reasons to expect NLD victory. Under the country’s complex political system, the mainstream party among the ethnic Bamar majority always win the polls. In the population at large, a victory for the NLD is regarded as the most likely way to prevent a return to military government. The Covid-19 crisis and campaign restrictions hand all the political advantages to the NLD and incumbent authorities. ideas into movement • To improve election performance, ethnic nationality parties are introducing a number of new measures, including “party mergers” and “no-compete” agreements.