Working Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar UNAIDS

Annual Progress Report, 1 Apr 2006 - 31 Mar 2007 Table of Contents Foreword 3 About this report 5 Highlights in Achievements 7 Progress and Achievements 9 ....... Access to services to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV improved 9 ....... Access to services to prevent transmission of HIV in injecting drug use ....... improved 18 ....... Knowledge and attitudes improved 27 ....... Access to services for HIV care and support improved 30 Fund Management 41 ....... Programmatic and Financial Monitoring 41 ....... Financial Status and Utilisation of Funds 43 Operating Environment 44 Annexe 1: Implementing Partners expenditure and budgets 45 Annexe 2: Summary of Technical Progress Apr 2004–Mar 2007 49 Annexe 3: Achievements by Implementing Partners Round II, II(b) 50 Annexe 4: Guiding principles for the provision of humanitarian assistance 57 Acronyms and abbreviations 58 1 Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar UNAIDS 2 Annual Progress Report, 1 Apr 2006 - 31 Mar 2007 Foreword This report will be the last for the Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar (FHAM), covering its fourth and final year of operation (the fiscal year from April 2006 through March 2007). Created as a pooled funding mechanism in 2003 to support the United Nations Joint Programme on AIDS in Myanmar, the FHAM has demonstrated that international resources can be used to finance HIV services for people in need in an accountable and transparent manner. As this report details, progress has been made in nearly every area of HIV prevention – especially among the most at-risk groups related to sex work and drug use – and in terms of care and support, including anti-retroviral treatment. -

Mimu875v01 120626 3W Livelihoods South East

Myanmar Information Management Unit 3W South East of Myanmar Livelihoods Border and Country Based Organizations Presence by Township Budalin Thantlang 94°23'EKani Wetlet 96°4'E Kyaukme 97°45'E 99°26'E 101°7'E Ayadaw Madaya Pangsang Hakha Nawnghkio Mongyai Yinmabin Hsipaw Tangyan Gangaw SAGAING Monywa Sagaing Mandalay Myinmu Pale .! Pyinoolwin Mongyang Madupi Salingyi .! Matman CHINA Ngazun Sagaing Tilin 1 Tada-U 1 1 2 Monghsu Mongkhet CHIN Myaing Yesagyo Kyaukse Myingyan 1 Mongkaung Kyethi Mongla Mindat Pauk Natogyi Lawksawk Kengtung Myittha Pakokku 1 1 Hopong Mongping Taungtha 1 2 Mongyawng Saw Wundwin Loilen Laihka Ü Nyaung-U Kunhing Seikphyu Mahlaing Ywangan Kanpetlet 1 21°6'N Paletwa 4 21°6'N MANDALAY 1 1 Monghpyak Kyaukpadaung Taunggyi Nansang Meiktila Thazi Pindaya SHAN (EAST) Chauk .! Salin 4 Mongnai Pyawbwe 2 Tachileik Minbya Sidoktaya Kalaw 2 Natmauk Yenangyaung 4 Taunggyi SHAN (SOUTH) Monghsat Yamethin Pwintbyu Nyaungshwe Magway Pinlaung 4 Mawkmai Myothit 1 Mongpan 3 .! Nay Pyi Hsihseng 1 Minbu Taw-Tatkon 3 Mongton Myebon Langkho Ngape Magway 3 Nay Pyi Taw LAOS Ann MAGWAY Taungdwingyi [(!Nay Pyi Taw- Loikaw Minhla Nay Pyi Pyinmana 3 .! 3 3 Sinbaungwe Taw-Lewe Shadaw Pekon 3 3 Loikaw 2 RAKHINE Thayet Demoso Mindon Aunglan 19°25'N Yedashe 1 KAYAH 19°25'N 4 Thandaunggyi Hpruso 2 Ramree Kamma 2 3 Toungup Paukkhaung Taungoo Bawlakhe Pyay Htantabin 2 Oktwin Hpasawng Paungde 1 Mese Padaung Thegon Nattalin BAGOPhyu (EAST) BAGO (WEST) 3 Zigon Thandwe Kyangin Kyaukkyi Okpho Kyauktaga Hpapun 1 Myanaung Shwegyin 5 Minhla Ingapu 3 Gwa Letpadan -

The Union Report the Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Census Report Volume 2

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report The Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Volume Report : Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 1: Map of Myanmar by State, Region and District Census Report Volume 2 (Union) i Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is my hope that the main census results will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and Offices at all administrative levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

THAN, TUN Citation the ROYAL ORDERS of BURMA, AD 1598-1885

Title Summary of Each Order in English Author(s) THAN, TUN THE ROYAL ORDERS OF BURMA, A.D. 1598-1885 (1988), Citation 7: 1-158 Issue Date 1988 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/173887 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University THE ROYAL ORDERS OF BURMA, AD 1598-1885 The Roya 1Orders of Burma, Part Seven, AD 1811-1819 Summary 1 January 18 1 1 Order:( 1) According to statements made by the messengers from Ye Gaung Sanda Thu, Town Officer, Mogaung, arrest Ye Gaung Sanda Thu and bring him here as a prisoner; send an officer to succeed him in Mogaung as Town Officer. < 2) The King is going to plant the Maha Bodhi saplings on 3 January 1811; make necessary preparations. This Order was passed on 1 January 1811 and proclaimed by Baya Kyaw Htin, Liaison Officer- cum -Chief of Caduceus Bearers. 2 January 18 1 1 Order:( 1) Officer of Prince Pyay (Prome) had sent here thieves and robbers that they had arrested; these men had named certain people as their accomplices; send men to the localities where these accused people are living and with the help of the local chiefs, put them under custody. ( 2) Prince Pakhan shall arrest all suspects alledged to have some connection with the crimes committed in the villages of Ka Ni, Mait Tha Lain and Pa Hto of Kama township. ( 3) Nga Shwe Vi who is under arrest now is proved to be a leader of thieves; ask him who were his associates. This Order was passed on 2 January 1811 and proclaimed by Zayya Nawyatha, Liaison Officer. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Summary of War Crimes by Burma Army During Offensive in Central Shan State Since Oct 6, 2015

Summary of war crimes by Burma Army during offensive in central Shan State since Oct 6, 2015 Shelling/bombing of civilian targets Date Type of attack Targeted civilian area Oct 26, 2015 Shelling, causing civilian injury Wan Mwe Taw village, Waeng Kao tract, Mong Nawng township Oct 28, 2015 Shelling, causing civilian injury Wan Hai village (residential area), Ke See township Nov 9, 2015 Shelling causing damage to Mong Nawng town (est. 6,000 population) civilian houses Nov 10, 2015 Shelling and aerial bombing Mong Nawng town (est. 6,000 population) causing civilian injury and damage to civilian houses and school Nov 10, 2015 Shelling and aerial bombing Wan Saw village, Mong Hsu township (where causing damage to civilian houses over 1,500 displaced villagers were sheltering) Nov 12, 2015 Shelling causing damage to Mong Nawng town (est. 6,000 population) civilian houses Other abuses against civilians by Burma Army troops Date Villagers Type of abuse Location Oct 26, a 53-yr-old man Shot and injured by Wan Koong Nim, Hai Pa tract, Mong Hsu 2015 Burma Army troops township while fleeing shelling Nov 5, a 32-yr-old woman Gang-raped by Burma (village name withheld) Ke See township 2015 Army troops Nov 8, a 55-yr-old woman Shot and injured by Nr. Wan Hoong Kham, Waeng Kao tract, 2015 and a 15-yr-old boy Burma Army troops Mong Nawng township while returning from farm Nov 22, 17 villagers now Shot at by Burma Army Nr Mong Ark, Mong Hsu township 2015 missing, suspected troops while harvesting injured or killed rice Estimated number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) resulting from current offensive in central Shan State (November 23, 2015) No. -

Shan State Analysis

IMPACTS OF COVID-19 PANDEMIC ON RETURNING MIGRANTS SHAN STATE ANALYSIS Distributing items to returning migrants at a quarantine facility in Taunggyi, Shan State. © IOM 2020 OVERVIEW per cent of Shan State migrants surveyed had returned from abroad (5% internal returnees).2 Out This rapid assessment was conducted by Parami of a total 345 international migrants surveyed in Development Network (PDN), with the technical Shan State, 313 (91%) returned from Thailand and support of IOM and in close coordination with the 32 (9%) from China. Department of Labour. The assessment covered 10 townships, namely, Hopong, Lawksawk, Nansang, 33 per cent of returned migrants to Shan State said Taunggyi, Nyaungshwe, Loilen, Mawkmai, Pinlaung, they returned because they got scared of COVID-19 1 Hsihseng and Laihka. The objectives of the (men 35%; women 32%). 17 per cent said that they assessment were to: returned because they lost their job as a result of the pandemic, 15 per cent said they returned for 1. Understand the experiences, challenges and other reasons (but still related to the pandemic), and future intentions of returnees and 11 per cent said their families asked them to return communities of return after the COVID-19 outbreak. A further 22 per cent 2. Support an evidence-based response to the gave other reasons, including returning for the challenges faced by returning migrants as a Thingyan holidays (10%), increased hardships at result of the COVID pandemic destination (2%), to escape COVID-19 lockdown (1%), and reasons unrelated to the pandemic (9%). RETURN MIGRATION Before returning to Shan State, 18 per cent of Of the 2,311 returned migrants surveyed, 362 (men migrants said they had experienced increased 183; women 179) have returned to Shan State. -

English 2014

The Border Consortium November 2014 PROTECTION AND SECURITY CONCERNS IN SOUTH EAST BURMA / MYANMAR With Field Assessments by: Committee for Internally Displaced Karen People (CIDKP) Human Rights Foundation of Monland (HURFOM) Karen Environment and Social Action Network (KESAN) Karen Human Rights Group (KHRG) Karen Offi ce of Relief and Development (KORD) Karen Women Organisation (KWO) Karenni Evergreen (KEG) Karenni Social Welfare and Development Centre (KSWDC) Karenni National Women’s Organization (KNWO) Mon Relief and Development Committee (MRDC) Shan State Development Foundation (SSDF) The Border Consortium (TBC) 12/5 Convent Road, Bangrak, Suite 307, 99-B Myay Nu Street, Sanchaung, Bangkok, Thailand. Yangon, Myanmar. E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.theborderconsortium.org Front cover photos: Farmers charged with tresspassing on their own lands at court, Hpruso, September 2014, KSWDC Training to survey customary lands, Dawei, July 2013, KESAN Tatmadaw soldier and bulldozer for road construction, Dawei, October 2013, CIDKP Printed by Wanida Press CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 3 1.1 Context .................................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................ -

The United Nations in Myanmar

The United Nations in Myanmar United Nations Resident & Humanitarian Coordinator LEGEND Ms. Renata Dessallien Produced by : MIMU Date : 4 May 2016 Field Presence (By Office/Staff) Data Source : UN Agencies in Myanmar The United Nations (UN) has been present in Myanmar and assisting vulnerable populations since the country gained its independence in 1948. Head Office The UN Resident/Humanitarian Coordinator (UN RC/HC) is the chief UN official in Myanmar for humanitarian, recovery and Development activities. The UN country-level coordination is managed by the UN Country Team (UNCT) and led by the UN RC/HC. OTHER ENTITIES AND ASSOCIATE COORDINATION FUNDS AND PROGRAMMES SPECIALIZED AGENCIES AGENCIES UN- World UNRC /HC UNO CHA UN IC MIM U UND SS UNIC EF UN DP UNH CR UNO DC UNF PA WF P UNE SCO FA O UNI DO ILO WH O UNA IDS OHC HR UNO PS U N IO M IM F Office of the UN Coordin ation of Informatio n Centre Inform ation Safety and Children 's Fund Develo pment High Com missioner HABI TAT Office on D rugs and Population Fund World Food Educationa l, Scientific Food & Ag ricultural Industrial D evelopment Internation al Labour World Health Joint Prog ramme on High Com missioner Office for Project Interna tional Ban k Intern ational Resident/Humanitarian Humanitarian Affairs Management Unit Security Programme for Refugees Human Settlements Crime Programme & Cultural Organization Organization Organization Organization Organization HIV/AIDS for Human Rights Services WOMEN Organization for Monetary Fund Coordinator Programme Migration Group MANDATES To -

China Thailand Laos

MYANMAR IDP Sites in Shan State As of 30 June 2021 BHUTAN INDIA CHINA BANGLADESH MYANMAR Nay Pyi Taw LAOS KACHIN THAILAND CHINA List of IDP Sites In nothern Shan No. State Township IDP Site IDPs 1 Hseni Nam Sa Larp 267 2 Hsipaw Man Kaung/Naung Ti Kyar Village 120 3 Bang Yang Hka (Mung Ji Pa) 162 4 Galeng (Palaung) & Kone Khem 525 5 Galeng Zup Awng ward 5 RC 134 6 Hu Hku & Ho Hko 131 SAGAING Man Yin 7 Kutkai downtown (KBC Church) 245 Man Pying Loi Jon 8 Kutkai downtown (KBC Church-2) 155 Man Nar Pu Wan Chin Mu Lin Huong Aik 9 Mai Yu Lay New (Ta'ang) 398 Yi Hku La Shat Lum In 22 Nam Har 10 Kutkai Man Loi 84 Ngar Oe Shwe Kyaung Kone 11 Mine Yu Lay village ( Old) 264 Muse Nam Kut Char Lu Keng Aik Hpan 12 Mung Hawm 170 Nawng Mo Nam Kat Ho Pawt Man Hin 13 Nam Hpak Ka Mare 250 35 ☇ Konkyan 14 Nam Hpak Ka Ta'ang ( Aung Tha Pyay) 164 Chaung Wa 33 Wein Hpai Man Jat Shwe Ku Keng Kun Taw Pang Gum Nam Ngu Muse Man Mei ☇ Man Ton 15 New Pang Ku 688 Long Gam 36 Man Sum 16 Northern Pan Law 224 Thar Pyauk ☇ 34 Namhkan Lu Swe ☇ 26 Kyu Pat 12 KonkyanTar Shan Loi Mun 17 Shan Zup Aung Camp 1,084 25 Man Set Au Myar Ton Bar 18 His Aw (Chyu Fan) 830 Yae Le Man Pwe Len Lai Shauk Lu Chan Laukkaing 27 Hsi Hsar 19 Shwe Sin (Ward 3) 170 24 Tee Ma Hsin Keng Pang Mawng Hsa Ka 20 Mandung - Jinghpaw 147 Pwe Za Meik Nar Hpai Nyo Chan Yin Kyint Htin (Yan Kyin Htin) Manton Man Pu 19 Khaw Taw 21 Mandung - RC 157 Aw Kar Shwe Htu 13 Nar Lel 18 22 Muse Hpai Kawng 803 Ho Maw 14 Pang Sa Lorp Man Tet Baing Bin Nam Hum Namhkan Ho Et Man KyuLaukkaing 23 Mong Wee Shan 307 Tun Yone Kyar Ti Len Man Sat Man Nar Tun Kaw 6 Man Aw Mone Hka 10 KutkaiNam Hu 24 Nam Hkam - Nay Win Ni (Palawng) 402 Mabein Ton Kwar 23 War Sa Keng Hon Gyet Pin Kyein (Ywar Thit) Nawng Ae 25 Namhkan Nam Hkam (KBC Jaw Wang) 338 Si Ping Kaw Yi Man LongLaukkaing Man Kaw Ho Pang Hopong 9 16 Nar Ngu Pang Paw Long Htan (Tart Lon Htan) 26 Nam Hkam (KBC Jaw Wang) II 32 Ma Waw 11 Hko Tar Say Kaw Wein Mun 27 Nam Hkam Catholic Church ( St. -

Map of Myanmar

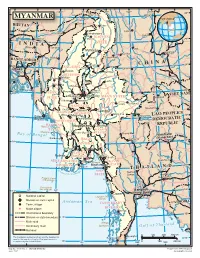

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations. -

BICAS Working Paper 14 Woods

Working 14 Paper CP maize contract farming in Shan State, Myanmar: A regional case of a place-based corporate agro-feed system Kevin Woods May 2015 1 CP maize contract farming in Shan State, Myanmar: A regional case of a place‐based corporate agro‐feed system by Kevin Woods Published by: BRICS Initiative for Critical Agrarian Studies (BICAS) in collaboration with: Universidade de Brasilia Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP) Campus Universitário Darcy Ribeiro Rua Quirino de Andrade, 215 Brasília – DF 70910‐900 São Paulo ‐ SP 01049010 Brazil Brazil Tel: +55 61 3107‐3300 Tel: +55‐11‐5627‐0233 E‐mail: [email protected] E‐mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.unb.br/ Website: www.unesp.br Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Transnational Institute Av. Paulo Gama, 110 ‐ Bairro Farroupilha PO Box 14656 Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul 1001 LD Amsterdam Brazil The Netherlands Tel: +55 51 3308‐3281 Tel: +31 20 662 66 08 Fax: +31 20 675 71 76 E‐mail: [email protected] E‐mail: [email protected] Website: www.ufrgs.br/ Website: www.tni.org Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS) International Institute of Social Studies University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17 P.O. Box 29776 Bellville 7535, Cape Town 2502 LT The Hague South Africa The Netherlands Tel: +27 21 959 3733 Fax: +27 21 959 3732 Tel: +31 70 426 0460 Fax: +31 70 426 079 E‐mail: [email protected] E‐mail: [email protected] Website: www.plaas.org.za Website: www.iss.nl College of Humanities and Development Studies Future Agricultures Consortium China Agricultural University Institute of Development Studies No.