Myanmar Update February 2016 Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B U R M a B U L L E T

B U R M A B U L L E T I N ∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞A month-in-review of events in Burma∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞ A L T E R N A T I V E A S E A N N E T W O R K O N B U R M A campaigns, advocacy & capacity-building for human rights & democracy Issue 20 August 2008 • Fearing a wave of demonstrations commemorating th IN THIS ISSUE the 20 anniversary of the nationwide uprising, the SPDC embarks on a massive crackdown on political KEY STORY activists. The regime arrests 71 activists, including 1 August crackdown eight NLD members, two elected MPs, and three 2 Activists arrested Buddhist monks. 2 Prison sentences • Despite the regime’s crackdown, students, workers, 3 Monks targeted and ordinary citizens across Burma carry out INSIDE BURMA peaceful demonstrations, activities, and acts of 3 8-8-8 Demonstrations defiance against the SPDC to commemorate 8-8-88. 4 Daw Aung San Suu Kyi 4 Cyclone Nargis aid • Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is allowed to meet with her 5 Cyclone camps close lawyer for the first time in five years. She also 5 SPDC aid windfall receives a visit from her doctor. Daw Suu is rumored 5 Floods to have started a hunger strike. 5 More trucks from China • UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in Burma HUMAN RIGHTS 5 Ojea Quintana goes to Burma Tomás Ojea Quintana makes his first visit to the 6 Rape of ethnic women country. The SPDC controls his meeting agenda and restricts his freedom of movement. -

Burma Coup Watch

This publication is produced in cooperation with Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN), Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Progressive Voice (PV), US Campaign for Burma (USCB), and Women Peace Network (WPN). BN 2021/2031: 1 Mar 2021 BURMA COUP WATCH: URGENT ACTION REQUIRED TO PREVENT DESTABILIZING VIOLENCE A month after its 1 February 2021 coup, the military junta’s escalation of disproportionate violence and terror tactics, backed by deployment of notorious military units to repress peaceful demonstrations, underlines the urgent need for substantive international action to prevent massive, destabilizing violence. The junta’s refusal to receive UN diplomatic and CONTENTS human rights missions indicates a refusal to consider a peaceful resolution to the crisis and 2 Movement calls for action confrontation sparked by the coup. 2 Coup timeline 3 Illegal even under the 2008 In order to avert worse violence and create the Constitution space for dialogue and negotiations, the 4 Information warfare movement in Burma and their allies urge that: 5 Min Aung Hlaing’s promises o International Financial Institutions (IFIs) 6 Nationwide opposition immediately freeze existing loans, recall prior 6 CDM loans and reassess the post-coup situation; 7 CRPH o Foreign states and bodies enact targeted 7 Junta’s violent crackdown sanctions on the military (Tatmadaw), 8 Brutal LIDs deployed Tatmadaw-affiliated companies and partners, 9 Ongoing armed conflict including a global arms embargo; and 10 New laws, amendments threaten human rights o The UN Security Council immediately send a 11 International condemnation delegation to prevent further violence and 12 Economy destabilized ensure the situation is peacefully resolved. -

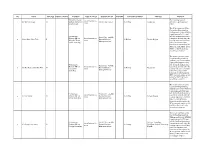

Warrant Lists English

No Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Minister of Social For encouraging civil Issued warrant to 1 Dr. Win Myat Aye M Welfare, Relief and Penal Code S:505-a In Hiding Naypyitaw servants to participate in arrest Resettlement CDM The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and Pyihtaungsu self-declared parliamentary Penal Code - 505(B), Hluttaw MP for Issued warrant to committee formed after the 2 (Daw) Phyu Phyu Thin F Natural Disaster In Hiding Yangon Region Mingalar Taung arrest coup in response to military Management law Nyunt Township rule. The warrants were issued at each township the MPs represent, under article 505[b) of the Penal Code, according to sources. The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and Pyihtaungsu self-declared parliamentary Penal Code - 505(B), Hluttaw MP for Issued warrant to committee formed after the 3 (U) Yee Mon (aka) U Tin Thit M Natural Disaster In Hiding Naypyitaw Potevathiri arrest coup in response to military Management law Township rule. The warrants were issued at each township the MPs represent, under article 505[b) of the Penal Code, according to sources. The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and self-declared parliamentary Pyihtaungsu Penal Code - 505(B), Issued warrant to committee formed after the 4 (U) Tun Myint M Hluttaw MP for Natural Disaster In Hiding Yangon Region arrest coup in response to military Bahan Township Management law rule. -

CRC Shadow Report Burma the Plight of Children Under Military Rule in Burma

CRC Shadow Report Burma The plight of children under military rule in Burma Child Rights Forum of Burma 29th April 2011 Assistance for All Political Prisoners-Burma (AAPP-B), Burma Issues ( BI), Back Pack Health Worker Team(BPHWT) and Emergency Action Team (EAT), Burma Anti-Child Trafficking (Burma-ACT), Burmese Migrant Workers Education Committee (BMWEC), Chin Human Rights Organization (CHRO), Committee For Protection and Promote of Child Rights-Burma (CPPCR-Burma), Foundation for Education and Development (FED)/Grassroots Human Rights Education (GHRE), Human Rights Education Institute of Burma (HREIB), Karen Human Rights Group (KHRG), Karen Youth Organization (KYO), Kachin Women’s Association Thailand (KWAT), Mae Tao Clinic (MTC), Oversea Mon Women’s Organization (OMWO), Social Action for Women (SAW),Women and Child Rights Project (WCRP) and Human Rights Foundation of Monland (HURFOM),Yoma 3 News Service (Burma) TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 Acknowledgement 3 Introduction 3 Purpose and Methodology of the Report 4 Articles 24 and 27 ‐ the right to health and an adequate standard of living 6 Access to Health Services 7 Child Malnutrition 8 Maternal health 9 Denial of the right to health for children in prisons 10 Article 28 – Right to education 13 Inadequate teacher salaries 14 Armed conflict and education 15 Education for girls 16 Discrimination in education 16 Human Rights Education 17 Article 32–Child Labour 19 Forced Labour 20 Portering for the Tatmadaw 21 Article 34 and 35 ‐ Trafficking in Children 23 Corruption and restrictions -

Women Arrested & Charged List

ARRESTS No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark S: 8 of the Export and Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Import Law and S: 25 leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and of the Natural Superintendent Kyi President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Disaster Management Lin of Special Branch, 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and law, Penal Code - Dekkhina District regions were also detained. 505(B), S: 67 of the Administrator Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Chief Minister of Karen State President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 1-Feb-21 and 8- Detained in Hpa-An 2 (Daw) Nan Khin Htwe Myint F (Central Executive Committee Karen State chief ministers and ministers in the states and Feb-21 Prison Member of NLD) regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Telecommunications Ayeyarwady 3 Dr. Hla Myat Thway F Minister of Social Affairs 1-Feb-21 Detained chief ministers and ministers in the states and Law - 66(D) Region regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Minister of Karen Ethnic Affairs of Detained in Insein 4 Naw Pan Thinzar Myo F 1-Feb-21 Rangoon Region chief ministers and ministers in the states and Rangoon Region Government Prison regions were also detained. -

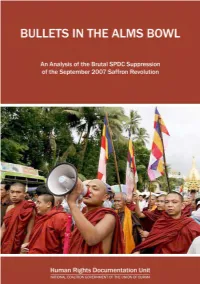

Bullets in the Alms Bowl

BULLETS IN THE ALMS BOWL An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution March 2008 This report is dedicated to the memory of all those who lost their lives for their part in the September 2007 pro-democracy protests in the struggle for justice and democracy in Burma. May that memory not fade May your death not be in vain May our voices never be silenced Bullets in the Alms Bowl An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution Written, edited and published by the Human Rights Documentation Unit March 2008 © Copyright March 2008 by the Human Rights Documentation Unit The Human Rights Documentation Unit (HRDU) is indebted to all those who had the courage to not only participate in the September protests, but also to share their stories with us and in doing so made this report possible. The HRDU would like to thank those individuals and organizations who provided us with information and helped to confirm many of the reports that we received. Though we cannot mention many of you by name, we are grateful for your support. The HRDU would also like to thank the Irish Government who funded the publication of this report through its Department of Foreign Affairs. Front Cover: A procession of Buddhist monks marching through downtown Rangoon on 27 September 2007. Despite the peaceful nature of the demonstrations, the SPDC cracked down on protestors with disproportionate lethal force [© EPA]. Rear Cover (clockwise from top): An assembly of Buddhist monks stage a peaceful protest before a police barricade near Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon on 26 September 2007 [© Reuters]; Security personnel stepped up security at key locations around Rangoon on 28 September 2007 in preparation for further protests [© Reuters]; A Buddhist monk holding a placard which carried the message on the minds of all protestors, Sangha and civilian alike. -

ASA 16/04/00 Unsung Heroines: the Women of Myanmar

UNSUNG HEROINES: THE WOMEN OF MYANMAR INTRODUCTION Women in Myanmar have been subjected to a wide range of human rights violations, including political imprisonment, torture and rape, forced labour, and forcible relocation, all at the hands of the military authorities. At the same time women have played an active role in the political and economic life of the country. It is the women who manage the family finances and work alongside their male relatives on family farms and in small businesses. Women have been at the forefront of the pro-democracy movement which began in 1988, many of whom were also students or female leaders within opposition political parties. The situation of women in Myanmar was raised most recently in April 2000 at the United Nations Commission on Human Rights and in January 2000 by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the expert body which monitors States parties’ compliance with the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.1 CEDAW considered the initial report by the Government of Myanmar on measures taken to implement the provisions of the Convention at its Twenty-second session in New York. Prior to its consideration, Amnesty International made a submission to the Committee, which outlined the organization’s concerns in regards to the State Peace and Development Council’s (SPDC, Myanmar’s military government) compliance with the provisions of the Convention. During the military’s violent suppression of the mass pro- democracy movement in 1988, women in Myanmar were arrested, Rice farmers c. Chris Robinson tortured, and killed by the security forces. -

Myanmar: Ethnic Politics and the 2020 General Election

MYANMAR POLICY BRIEFING | 23 | September 2020 Myanmar: Ethnic Politics and the 2020 General Election KEY POINTS • The 2020 general election is scheduled to take place at a critical moment in Myanmar’s transition from half a century under military rule. The advent of the National League for Democracy to government office in March 2016 was greeted by all the country’s peoples as the opportunity to bring about real change. But since this time, the ethnic peace process has faltered, constitutional reform has not started, and conflict has escalated in several parts of the country, becoming emergencies of grave international concern. • Covid-19 represents a new – and serious – challenge to the conduct of free and fair elections. Postponements cannot be ruled out. But the spread of the pandemic is not expected to have a significant impact on the election outcome as long as it goes ahead within constitutionally-appointed times. The NLD is still widely predicted to win, albeit on reduced scale. Questions, however, will remain about the credibility of the polls during a time of unprecedented restrictions and health crisis. • There are three main reasons to expect NLD victory. Under the country’s complex political system, the mainstream party among the ethnic Bamar majority always win the polls. In the population at large, a victory for the NLD is regarded as the most likely way to prevent a return to military government. The Covid-19 crisis and campaign restrictions hand all the political advantages to the NLD and incumbent authorities. ideas into movement • To improve election performance, ethnic nationality parties are introducing a number of new measures, including “party mergers” and “no-compete” agreements. -

Burma's 2015 Parliamentary Elections: Issues for Congress

Burma’s 2015 Parliamentary Elections: Issues for Congress Michael F. Martin Specialist in Asian Affairs March 28, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44436 Burma’s 2015 Parliamentary Elections: Issues for Congress Summary The landslide victory of Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) in Burma’s November 2015 parliamentary elections may prove to be a major step in the nation’s potential transition to a more democratic government. Having won nearly 80% of the contested seats in the election, the NLD has a majority in both chambers of the Union Parliament, which gave it the ability to select the President-elect, as well as control of most of the nation’s Regional and State Parliaments. Burma’s 2008 constitution, however, grants the Burmese military, or Tatmadaw, widespread powers in the governance of the nation, and nearly complete autonomy from civilian control. One quarter of the seats in each chamber of the Union Parliament are reserved for military officers appointed by the Tatmadaw’s Commander-in-Chief, giving them the ability to block any constitutional amendments. Military officers constitute a majority of the National Defence and Security Council, an 11-member body with some oversight authority over the President. The constitution also grants the Tatmadaw “the right to independently administer and adjudicate all affairs of the armed services,” and designates the Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services as “the ‘Supreme Commander’ of all armed forces,” which could have serious implications for efforts to end the nation’s six-decade-long, low-grade civil war. -

1 Health, Humanitarian Care and Human Rights in Burma

HEALTH, HUMANITARIAN CARE AND HUMAN RIGHTS IN BURMA The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social conditions. World Health Organisation Constitution (Preamble) 1. OVERVIEW 2. HEALTH RIGHTS AND HUMAN RIGHTS: THE EXPERIENCE OF BURMA 3. THE HEALTH SYSTEM IN BURMA 4. HEALTH IN A SOCIETY UNDER CENSORSHIP 5. POLITICAL RESTRICTIONS ON MEDICAL PRACTITIONERS 6. CONFLICT AND HUMANITARIAN CRISIS 6.1 THE BACKDROP OF WAR 6.2 REFUGEES AND INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT OF CIVILIANS 6.3 THE HEALTH TREATMENT OF PRISONERS 7. AIDS AND NARCOTICS 8. WOMEN AND HEALTH 9. THE INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE 10. RECOMMENDATIONS 1 ABBREVIATIONS ASEAN Association of South East Asian Nations BADP Border Areas Development Programme BBC British Broadcasting Corporation BSPP Burma Socialist Programme Party DKBO Democratic Karen Buddhist Organisation ICRC International Committee of the Red Cross KIO Kachin Independence Organisation KNU Karen National Union KNPP Karenni National Progressive Party MMA Myanmar Medical Association MMCWA Myanmar Maternal and Child Welfare Association MRC Myanmar Red Cross MSF Medecins Sans Frontieres MTA Mong Tai Army NGO Non-Governmental Organisation NLD National League for Democracy SLORC State Law and Order Restoration Council UN United Nations UNDP United Nations Development Programme UNDCP United Nations International Drug Control Programme UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees UNICEF United Nations Children's Fund UNPFA United Nations Population Fund USDA Union Solidarity and Development Association UWSP United Wa State Party WHO World Health Organisation 2 1. OVERVIEW Censorship has long hidden a multitude of grave issues in Burma (Myanmar1). -

B149 Myanmar-S Peace Process

Myanmar’s Peace Process: Getting to a Political Dialogue Crisis Group Asia Briefing N°149 Yangon/Brussels, 19 October 2016 I. Overview The current government term may be the best chance for a negotiated political set- tlement to almost 70 years of armed conflict that has devastated the lives of minority communities and held back Myanmar as a whole. Aung San Suu Kyi and her admin- istration have made the peace process a top priority. While the previous government did the same, she has a number of advantages, such as her domestic political stature, huge election mandate and strong international backing, including qualified support on the issue from China. These contributed to participation by nearly all armed groups – something the former government had been unable to achieve – in the Panglong- 21 peace conference that commenced on 31 August. But if real progress is to be made, both the government and armed groups need to adjust their approach so they can start a substantive political dialogue as soon as possible. Pangalong-21 was important for its broad inclusion of armed groups, not for its content, and the challenges going forward should not be underestimated. Many groups attended not out of support for the process, but because they considered they had no alternative. Many felt that they were treated poorly and the conference was badly organised. The largest opposition armed group, the United Wa State Party (UWSP), sent only a junior delegation that walked out on the second day. An escalation of fighting in recent months, including use of air power and long-range artillery by the Myanmar military, has further eroded trust. -

Total Detention, Charge Lists English (Last Updated on 29 March 2021)

Date of Current No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Section of Law Plaintiff Address Remark Arrest Condition S: 8 of the Export Superinte and Import Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and ndent and S: 25 of the Senior NLD leaders including Daw Kyi Lin Natural Disaster Aung San Suu Kyi and President U of Special General Aung State Counsellor (Chairman of Management law, Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F 1-Feb-21 Branch, House Arrest Naypyitaw San NLD) Penal Code - chief ministers and ministers in the Dekkhina 505(B), S: 67 of states and regions were also detained. District the Administr Telecommunicatio ator ns Law S: 25 of the Superinte Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Natural Disaster ndent Senior NLD leaders including Daw Management law, Myint Aung San Suu Kyi and President U President (Vice Chairman-1 of Penal Code - Naing, Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw NLD) 505(B), S: 67 of Dekkhina chief ministers and ministers in the the District states and regions were also detained. Telecommunicatio Administr ns Law ator Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Speaker of the Union Assembly, Aung San Suu Kyi and President U the Joint House and Pyithu Win Myint were detained.