CRC Shadow Report Burma the Plight of Children Under Military Rule in Burma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myanmar: Conflicts and Human Rights Violations Continue to Cause Displacement

5 March 2009 Myanmar: Conflicts and human rights violations continue to cause displacement Displacement as a result of conflict and human rights violations continued in Myanmar in 2008. An estimated 66,000 people from ethnic minority communities in eastern Myanmar were forced to become displaced in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict and human rights abuses. As of October 2008, there were at least 451,000 people reported to be inter- nally displaced in the rural areas of eastern Myanmar. This is however a conservative fig- ure, and there is no information available on figures for internally displaced people (IDPs) in several parts of the country. In 2008, the displacement crisis continued to be most acute in Kayin (Karen) State in the east of the country where an intense offensive by the Myanmar army against ethnic insur- gent groups had been ongoing since late 2005. As of October 2008, there were reportedly over 100,000 IDPs in the state. New displacement was also reported in 2008 in western Myanmar’s Chin State as a result of human rights violations and severe food insecurity. People also continued to be displaced in some parts of the country due to a combination of coercive measures such as forced la- bour and land confiscation that left them with no choice but to migrate, often in the context of state-sponsored development initiatives. IDPs living in the areas of Myanmar still affected by armed conflict between the army and insurgent groups remained the most vulnerable, with their priority needs tending to be re- lated to physical security, food, shelter, health and education. -

ASEAN-India Strategic Partnership

A Think-Tank RIS of Developing Countries Research and Information System for Developing Countries (RIS), a New Delhi based autonomous think-tank under the Ministry of External Affairs, ASEAN-India Strategic Government of India, is an organisation that specialises in policy research on international economic issues and development cooperation. RIS is Partnership envisioned as a forum for fostering effective policy dialogue and capacity- building among developing countries on international economic issues. The focus of the work programme of RIS is to promote South-South ASEAN-India Strategic Partnership Perspectives from the Cooperation and assist developing countries in multilateral negotiations in ASEAN-India Network of Think-Tanks various forums. RIS is engaged in the Track II process of several regional initiatives. RIS is providing analytical support to the Government of India in the negotiations for concluding comprehensive economic cooperation agreements with partner countries. Through its intensive network of policy think-tanks, RIS seeks to strengthen policy coherence on international economic issues. For more information about RIS and its work programme, please visit its website: www.ris.org.in — Policy research to shape the international development agenda RIS Research and Information System for Developing Countries Core IV-B, Fourth Floor, India Habitat Centre Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110 003, India. Ph.: +91-11-24682177-80, Fax: +91-11-24682173-74 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ris.org.in ASEAN-India ASEAN Secretariat -

Hakha Chin Land and Resource Tenure Resource and Land Chin Hakha in Change and Persistence

PERSISTENCE AND CHANGE IN HAKHA CHIN LAND AND RESOURCETENURE PERSISTENCE AND CHANGE IN HAKHA CHIN LAND AND RESOURCE TENURE A STUDY ON LAND DYNAMICS IN THE PERIPHERY OF HAKHA M. Boutry, C. Allaverdian, Tin Myo Win, Khin Pyae Sone Of and Lives Land series Myanmar research Of Lives and Land Myanmar research series PERSISTENCE AND CHANGE IN HAKHA CHIN LAND AND RESOURCE TENURE A STUDY ON LAND DYNAMICS IN THE PERIPHERY OF HAKHA M. Boutry, C. Allaverdian, Tin Myo Win, Khin Pyae Sone Of Lives and Land Myanmar research series DISCLAIMER Persistence and change in Hakha Chin land and resource tenure: a study on land This document is supported with financial assistance from Australia, Denmark, dynamics in the periphery of Hakha. the European Union, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States of America, and Published by GRET, 2018 the Mitsubishi Corporation. The views expressed herein are not to be taken to reflect the official opinion of any of the LIFT donors. Suggestion for citation: Boutry, M., Allaverdian, C. Tin Myo Win, Khin Pyae Sone. (2018). Persistence and change in Hakha Chin land and resource tenure: a study on land dynamics in the periphery of Hakha. Of lives of land Myanmar research series. GRET: Yangon. Written by: Maxime Boutry and Celine Allaverdian With the contributions of: Tin Myo Win, Khin Pyae Sone and Sung Chin Par Reviewed by: Paul Dewit, Olivier Evrard, Philip Hirsch and Mark Vicol Layout by: studio Turenne Of Lives and Land Myanmar research series The Of Lives and Land series emanates from in-depth socio-anthropological research on land and livelihood dynamics. -

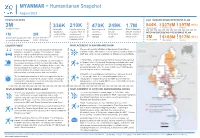

Myanmar – Humanitarian Snapshot (August 2021)

MYANMAR – Humanitarian Snapshot August 2021 PEOPLE IN NEED 2021 HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE PLAN 3M 336K 210K 470K 249K 1.7M 944K $276M $97M (35%) People targeted Requirements Received People in need Internally People internally Non-displaced Returnees and Other vulnerable displaced displaced due to stateless locally people, mostly in INTERIM EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN 1M 2M people at the clashes and persons in integrated urban and peri- start of 2021 Rakhine people urban areas people previously identified people identified insecurity since 2M $109M $17M (15%) February 2021 in conflict-affected areas since 1 February People targeted Requirements Received COUNTRYWIDE DISPLACEMENT IN KACHIN AND SHAN A total of 3 million people are targeted for humanitarian The overall security situation in Kachin and Shan states assistance across the country. This includes 1 million remains volatile, with various level of clashes reported between people in need in conflict-affected areas previously MAF and ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) or among EAOs. identified and a further 2 million people since 1 February. Monsoon flash floods affected around 125,000 people in In Shan State, small-scale population movement was reported the regions and states of Kachin, Kayin, Mandalay, Mon, in Hsipaw, Muse, Kyethi and Mongkaing townships since mid- Rakhine, eastern Shan and Tanintharyi between late July July. In total, 24,950 people have been internally displaced and mid-August, according to local actors. Immediate across Shan State since the start of 2021; over 5,000 people needs of families affected or evacuated have been remain displaced in five townships. addressed by local aid workers and communities. In Kachin, no new displacement has been reported. -

School Facilities in Matupi Township Chin State

Myanmar Information Management Unit School Facilities in Matupi Township Chin State 93°20’E 93°40’E 94°0’E INDIA Hriangpi B Hlungmang THANTLANG Aika Hriangpi A Sate Lungcawi Sabaungte HAKHA Leikang Khuataw Langli Siatlai Darling Calthawng B Siatlai Laungva Lan Pi Calthawng A Lunthangtalang Ruava B Sharshi Ruava A Lotaw Calthawng A Sabaungpi Sapaw Zuamang Rezua Rezua Tinia Rezua Sawti Nabung Taungla Hinthang (Aminpi) Pintia Hinthang (Aminpi) Hinthang (Adauk) Hinthang (Thangpi) Marlar Ramsai Tuphei 22°0’N 22°0’N Lungdaw Darcung Ramsi Kilung Balei Lalengpi Lungpharlia Siangngo Tisi Sempi Thangdia Vawti Lungngo Etang Khoboei Aru Thaunglan Longring Tinam Lungkam Tibing (Old) Tilat Tibing (New) Sungseng B Cangceh Sungseng A MATUPI Hungle Zesaw Thesi Lailengte B Tingsi Lailengte A Raso Soitaung Ta ng ku TILIN Sakhai Khuangang Baneng Radui Taungbu Pasing Sakhai A Renkheng Pakheng Amlai Boithia Daidin Din Pamai Satu Tibaw Kace Raw Var Thiol Kihlung Anhtaw Boiring B Luivang Ngaleng Thicong Ngaleng Boiring A Thangping Congthia 21°40’N Lungtung 21°40’N Daihnam Phaneng Lalui Khuabal Tinglong Vuitu Leiring B Leiring A Nhawte B Bonghung Khuahung Okla Matupi Khwar Bway (West,East) BEHS(1,2)-Madupi Leisin Nhawte A Taung Lun Ramting Kala Kha Ma Ya(304) Thlangpang A Theboi Valangte Thlangpang B Haltu Hatu (Upper) Wun Kai Vapung Valangpi Amsoi B Cangtak Amsoi A Belkhawng Tuisip Lungpang Palaro Kuica MINDAT Lingtui Pangtui Khengca Thungna Thotui Sihleh Ngapang Madu Mindat Raukthang Rung 21°20’N 21°20’N Boisip Mitu Vuilu PALETWA Legend Main Town Schools Other -

Initial Rapid Assessment of Selected Idp Settlements in Kayin and Tanintharyi, Myanmar

2013 Unicef Myanmar Nina Victoria Mattus Justiniani [INITIAL RAPID ASSESS MENT OF SELECTED IDP SETTLEMENTS IN KAYIN AND TANINTHARYI, MYANMAR] A report on 131 villages with internally displaced persons in Kayin state and Tanintharyi region, South East Myanmar. This report is based on an initial rapid assessment exercise carried out by volunteers from various faith-based organizations in late February to April, 2013. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... iv Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................................... v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 6 I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 10 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................................... 10 OBJECTIVES OF THE INITIAL RAPID ASSESSMENT .................................................................................. 10 METHODOLOGY, SCOPE AND LIMITATIONS ........................................................................................... 11 III. IDP CHILDREN AND THEIR VILLAGES ................................................................................................... -

The Union Report the Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Census Report Volume 2

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report The Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Volume Report : Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 1: Map of Myanmar by State, Region and District Census Report Volume 2 (Union) i Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is my hope that the main census results will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and Offices at all administrative levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

Dooplaya Situation Update: Kawkareik Township, January to October 2016

Situation Update July 18, 2017 / KHRG # 16-92-S1 Dooplaya Situation Update: Kawkareik Township, January to October 2016 This Situation Update describes events occurring in Kawkareik Township, Dooplaya District during the period between January and October 2016, and includes issues regarding army base locations, rape, drugs, villagers’ livelihood, military activities, refugee concerns, development, education, healthcare, land and taxation. • In the last two months, a Burmese man from A--- village raped and killed a 17-year-old girl. The man was arrested and was sent to Tatmadaw military police. The man who committed the rape was also under the influence of drugs. • Drug abuse has been recognised as an ongoing issue in Dooplaya District. Leaders and officials have tried to eliminate drugs, but the drug issue remains. • Refugees from Noh Poe refugee camp in Thailand are concerned that they will face difficulties if they return to Burma/Myanmar because Bo San Aung’s group (DKBA splinter group) started fighting with BGF and Tatmadaw when the refugees were preparing for their return to Burma/Myanmar. The ongoing fighting will cause problems for refugees if they return. Local people residing in Burma/Myanmar are also worried for refugees if they return because fighting could break out at any time. • There are many different armed groups in Dooplaya District who collect taxes. A local farmer reported that he had to pay a rice tax to many different armed groups, which left him with little money after. Situation Update | Kawkareik Township, Dooplaya District (January to October 2016) The following Situation Update was received by KHRG in November 2016. -

KAYAH STATE, LOIKAW DISTRICT Loikaw Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census KAYAH STATE, LOIKAW DISTRICT Loikaw Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Kayah State, Loikaw District Loikaw Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No.48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1 : Map of Kayah State, showing the townships Loikaw Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 128,401 2 Population males 63,109 (49.1%) Population females 65,292 (50.9%) Percentage of urban population 40.0% Area (Km2) 1,549.0 3 Population density (per Km2) 82.9 persons Median age 24.5 years Number of wards 13 Number of village tracts 12 Number of private households 26,495 Percentage of female headed households 24.1% Mean household size 4.6 persons4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 31.6% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 64.3% Elderly population (65+ years) 4.1% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 55.7 Child dependency ratio 49.2 Old dependency ratio 6.5 Ageing index 13.1 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 97 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 85.9% Male 90.6% Female 81.8% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 7,707 6.0 Walking 2,941 2.3 Seeing 4,457 3.5 Hearing 2,335 1.8 Remembering 3,029 2.4 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship Scrutiny 92,337 90.6 Associate -

Karen Community Consultation Report

Karen Community Consultation report 28th March 2009 Granville Town Hall Acknowledgements The Karen community consultation report was first compiled in June 2009 by the working group comprising of, Rhianon Partridge, Wah Wah Naw, Daniel Zu, Lina Ishu and Gary Cachia, with additional input provided by Jasmina Bajraktarevic Hayward This report and consultation was made possible by the relationships developed between STARTTS and the Karen community in Sydney and in particular with the Australian Karen Organisation. Special thanks to all people who participated in the consultation A copyright for this report belongs to STARTTS. Parts of the report may be reused for educational and non profit purposes without permission of STARTTS provided the report is adequately sourced. The report may be distributed electronically without permission. For further information or permissions please contact STARTTS on 02 97941900 STARTTS Karen Community Consultation Report Page 2 of 48 Contents Karen Information ........................................................................................................ 4 • Some of the history .............................................................................................. 4 • Persecution Past and Present ................................................................................ 7 • Demographics .................................................................................................... 13 • Karen Cultural information ............................................................................... -

Kayah State Myanmar South East Operation - UNHCR Hpa-An 31 March 2016

Return Assessments - Kayah State Myanmar South East Operation - UNHCR Hpa-An 31 March 2016 Background information Since June 2013, UNHCR has been piloting a system to assess spontaneous returns in the Southeast of Myanmar, a process that may start in the absence of an organized Voluntary Repatriation operation. Total Assessments 128 A verified return village, therefore, is a village where UNHCR field staff have confirmed there are refugees and/or IDPs who have returned since January 2012 with the intention of remaining Verified Return Villages permanently. During the assessments, communities are also asked whether their village is a refugee 44 village of origin, by definition a village that is home to people residing in a refugee camp in Thailand. A village where UNHCR completes an assessment can be both a verified return village and a refugee Refugee Villages of Origin 94 village of origin, as the two are not mutually exclusive. Using a “do no harm” approach based around community level discussion, the return assessment collect information about the patterns and needs of returnees in the Southeast. The project does not, however, attempt to represent the total number of returnees in a state, or the region as a whole. The returnee monitoring project has been underway in Kayah State, Mon State and Tanintharyi Region since June 2013, and expanded to Kayin State in December 2013. Verified Return Villages by Township ^^ ± Demoso 8 26 ^^^ ^^^^^ Hpasawng 11 ^ ^_^ ^ 5 ^ Loikaw 6 29 ^ ^_ Shadaw 19 ^ ^_ ^ 14 Shan (South) ^ ^_ ^ Bawlakhe 5 ^_Loikaw 2 ^ ^ ^_ Hpruso 7 29 ^_ ^_ ^_^_^_ Shadaw Mese 9 ^ ^_^_ ^ 2 ^^ ^_ ^_Demoso^^ ^_ Assessments Verified Return Villages ^^^ ^_^_ ^ ^ ^_ ^ ^_ ^^_^ ^^^ ^_ No. -

3 Sides to Every Story

33 SSIDES TO EEVERY SSTORY A PROFILE OF MUSLIM COMMUNITIES IN THE REFUGEE CAMPS ON THE THAILAND BURMA BORDER THAILAND BURMA BORDER CONSORTIUM JULY 2010 Note on the Title: The “three sides” refers to the three self-identified sectors of Muslim communities in the camps, defined by the reasons for their presence in the camps (see “Muslim Lifestyle Practices and Preferences/ Socio-Cultural/ Self-identity”). Cover design: http://library.wustl.edu/subjects/islamic/MihrabIsfahan.jpg 2 33 SSIDES TO EEVERY SSTORY A PROFILE OF MUSLIM COMMUNITIES IN THE REFUGEE CAMPS ON THE THAILAND BURMA BORDER THAILAND BURMA BORDER CONSORTIUM JULY 2010 3 CONTENTS PAGE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ……….......………………………………………………….……………………………. 7 SUMMARY OF STATISTICS BY RELIGION/CAMP ……………………………………………………………....... 9 PREFACE ……….......………………………………………………….……………………………………… 13 BACKGROUND INTRODUCTION OF ISLAM TO BURMA ………………………………………………………………………...... 15 DISPLACEMENT OF BURMESE MUSLIM COMMUNITIES INTO THAILAND ……..……………………………………… 15 Border-wide Camp-Specific Other Influxes CURRENT SITUATION PREVALENCE OF MUSLIM COMMUNITIES IN AND AROUND THE REFUGEE CAMPS ……..……………………. 19 Muslim Communities in Camps Muslim Communities Around the Camps Impacts on Camp Security LIFESTYLE PRACTICES AND PREFERENCES: SOCIO-CULTURAL: ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 21 o The “Three Sides” o Religion and Faith o Gender Roles o Romance, Marriage and Divorce o Social Inclusion FOOD AND SHELTER: ………….…...………………..…………………………….…………………….. 29 o Ration Collection/ Consumption o Ration/ Diet Supplementation