ASEAN-India Strategic Partnership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elephant Foot Yam Production in Southern Chin State ______

Value Chain Assessment: Elephant Foot Yam Production In Southern Chin State ___________________________________________________________________________________ January 2017 Commissioned by MIID and authored by Jon Keesecker, Trevor Gibson, and Tluang Chin Sung. Acknowledgements The report authors would like to thank Duncan MacQueen, Marc Le Quentrec, and Derek Glass for sharing their research into elephant foot yam production in Myanmar. This document has been produced for the Regional Community Forestry Training Center for Asia and the Pacific (RECOFTC) on behalf of the Myanmar Institute for Integrated Development (MIID) with funding from the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the consultants and do not necessarily reflect those of RECOFTC, MIID, the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs or any other stakeholder. MIID - Myanmar Institute for Integrated Development 12, Kanbawza Street Yangon Myanmar Phone +95 1 545170 [email protected] Myanmar Institute for Integrated Development | 2 Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 1.1 CONTEXT AND BACKGROUND 1.2 MAIN FINDINGS 1.3 RECOMMENDATIONS 2. RESEARCH BACKGROUND 6 2.1 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES 2.2 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 3. HISTORY OF EFY INDUSTRY IN CHIN STATE 8 4. BACKGROUND: CULTIVATION, PROCESSING AND MARKETS 10 4.1 TAXONOMY AND CHARACTERISTICS 4.2 CULTIVATION 4.3 CHIP PROCESSING 4.4 POWDER PROCESSING 4.5 MARKETS 5. OVERVIEW OF EFY VALUE CHAIN 18 5.1 ACTORS IN THE VALUE CHAIN 5.2 ENABLING ENVIRONMENT 5.3 SUPPORT SERVICES 5.4 SALES CHANNELS AND AGGREGATE OUTPUT 5.5 VALUE ADDITION 6. ANALYSIS OF VALUE CHAIN 29 6.1 ANALYSIS OF ACTOR CHOICE AND RATIONALE 6.2 ASSESSMENT OF MARKET PROSPECTS 6.3 COMPETITION WITHIN MYANMAR 7. -

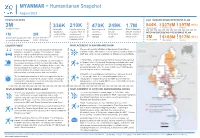

Myanmar – Humanitarian Snapshot (August 2021)

MYANMAR – Humanitarian Snapshot August 2021 PEOPLE IN NEED 2021 HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE PLAN 3M 336K 210K 470K 249K 1.7M 944K $276M $97M (35%) People targeted Requirements Received People in need Internally People internally Non-displaced Returnees and Other vulnerable displaced displaced due to stateless locally people, mostly in INTERIM EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN 1M 2M people at the clashes and persons in integrated urban and peri- start of 2021 Rakhine people urban areas people previously identified people identified insecurity since 2M $109M $17M (15%) February 2021 in conflict-affected areas since 1 February People targeted Requirements Received COUNTRYWIDE DISPLACEMENT IN KACHIN AND SHAN A total of 3 million people are targeted for humanitarian The overall security situation in Kachin and Shan states assistance across the country. This includes 1 million remains volatile, with various level of clashes reported between people in need in conflict-affected areas previously MAF and ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) or among EAOs. identified and a further 2 million people since 1 February. Monsoon flash floods affected around 125,000 people in In Shan State, small-scale population movement was reported the regions and states of Kachin, Kayin, Mandalay, Mon, in Hsipaw, Muse, Kyethi and Mongkaing townships since mid- Rakhine, eastern Shan and Tanintharyi between late July July. In total, 24,950 people have been internally displaced and mid-August, according to local actors. Immediate across Shan State since the start of 2021; over 5,000 people needs of families affected or evacuated have been remain displaced in five townships. addressed by local aid workers and communities. In Kachin, no new displacement has been reported. -

Infrastructure and Urban Development Plans P in Chin State

Chin State Investment and Product Fair 16th March 2019 Myanmar Convention Center, Yangon Infrastructure and Urban Development Plans in Chin State Daw Aye Aye Myint Deputy Director General Department of Urban and Housing Development Ministry of Construction Contents • Business opportunities to invest in road infrastructure in Chin State • National Spppatial Development Framework Plan • Urban and Regional Planning • Hierarchy of Urban Development Planning • Urbanization, Population and Potential in Chin State • Town Development Concept Plans in Chin State • Urban System, Urban Transformation and the Role of Cities in Chin State Overview of Chin State Area 36000 Square kilometer (5. 3%) of the whole Myanmar Population 518,614 (1.02%) of the whole Myanmar Total length of Road in Chin State -10770.76 kilometer Total Length of Roads in Chin State Under DOH -2119.329 km (1316 miles 7.25 Furlong) Total Length of Union Roads in Chin State Under DOH -(8) Roads 687. 0 km (426 mile 7 Furlong) Total Length of Provisional Roads in Chin State Under DOH-(25) Roads (1432.35km) (ill)(890 mil 0.12 Furlong) Government Budgets (2018-2019) - Union Budget - 16296.589 million (MMK) - Chin State Budget - 71541.493 million (MMK) Total - 87838.082 million (()MMK) Road Density - 0.059 km/km² - 4.09 km per 1000 people Per Capita Financing - 169370/- MMK Per Capita Annual Income -737636 MMK(2017-2018) Connectivity Dominant - Transport Linkage Objective - Movement of Peopp()le and Goods/ Tourism and Business(Trade)etc., Mode - (6) modes . Railway . Road -

CWG) Meeting Date/ Time & Venue 5 November 2020, 10.00 – 12.00 (Via Webex)

FINAL: Summary Note on Cash Working Group (CWG) Meeting Date/ Time & Venue 5 November 2020, 10.00 – 12.00 (via Webex) Chair / Co-chair WFP (Thin Thin Aye), Mercy Corps (John Nelson) and MRCS (Moe Thida Win) Participants ACF, ACTED, Action Aid, American Red Cross, AVSI, CARE, Christian Aid, CIDA, CRS, DFID, DRC, ECHO, FCA, Helvetas, ICRC, IRC, IRW, LIFT, Malteser, MA-UK, Mercy Corps, Metta, MRCS, NRC, OCHA, PUI_ DPC, Solidarites, Tearfund, Trócaire, UNDP, UNHCR, UNICEF – Social Protection/WASH, USAID, WFP, WHH, World Vision Agenda items and summary of discussion Action Points 1. Program updates WFP updated that 83 percent of the WFP emergency response in central Rakhine is now under full cash-based transfer (CBT). The first batch of e-cash in Sittwe will be sent to the beneficiaries by wave money on 6 November, and the second batch is planned for the second week of November. WFP started distributing 2,500 keypad phones to support households that have no access to mobile phones. There were some pending from the September cycle, and SMS will be sent to them during the first week of November. WFP provided monthly food and cash assistance to 45,000 beneficiaries in Kachin and about 7,000 in northern Shan. WFP also assisted 500 HIV/TB patients in Yangon and some 2,000 beneficiaries in urban Yangon. There was a question on the plan to expand the programme in central Rakhine. Finding a financial service provider is one of the challenges in implementing e-cash in Rakhine. WFP conducted a pilot cash programme in Meezar, Paletwa rural, as the beneficiaries in the area have access to rice from nearby markets, though at more than double the normal market price. -

'Threats to Our Existence'

Threats to Our Existence: Persecution of Ethnic Chin Christians in Burma Chin Human Rights OrganizaƟ on Threats to Our Existence: Persecution of Ethnic Chin Christians in Burma September, 2012 © Chin Human Rights OrganizaƟ on 2 Montavista Avenue Nepean ON K2J 2L3 Canada www.chro.ca Photos © CHRO Front cover: Chin ChrisƟ ans praying over a cross they were ordered to destroy by the Chin State authoriƟ es, Mindat township, July 2010. Back cover: Chin ChrisƟ an revival group in Kanpetlet township, May 2010. Design & PrinƟ ng: Wanida Press, Thailand ISBN: 978-616-305-461-6 Threats to Our Existence: PersecuƟ on of ethnic Chin ChrisƟ ans in Burma i Contents CONTENTS ......................................................................................................................... i Figures and appendices .................................................................................................. iv Acronyms ....................................................................................................................... v DedicaƟ on ...................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ viii About the Chin Human Rights OrganizaƟ on................................................................... ix RaƟ onale and methodology ........................................................................................... ix Foreword ....................................................................................................................... -

Acknowledgements This Report Was Developed by Representatives from the Chin State Health Department, Central Mohs Department Of

Acknowledgements This report was developed by representatives from the Chin State Health Department, Central MoHS Department of Public Health, Central MoHS Department of Medical Services, National Health Plan Implementation Monitoring Unit (NIMU) from the Ministry of Health and Sports, and the Three Millennium Development Goal Fund (3MDG). The team responsible for the Chin Health Report 2018 would like to thank the Chin State Health Director and Deputy Chin State Health Director, and representatives from State Health Departments for their guidance and contribution to the development of this report. Special thanks goes to all the Township Medical Officers and Basic Health Staffs from all the nine townships of Chin State for their cooperation and profound contribution to data gathering and coordination at township level. The team´s gratitude also goes to the State Government, Implementing Partners (INGOs, UN agencies, Civil Society Organizations) and donors for providing valuable inputs. Lastly, the team would like to thank all partners that have provided financial as well as technical support throughout the whole process. National Health Plan Implementation Monitoring Unit (NIMU) NIMU is a dedicated unit under the Minister’s Office, Ministry of Health and Sports Myanmar (MoHS). NIMU coordinates and facilitates the execution of activities included in the National Health Plan (2017-2021) and Annual Operational Plans together with all the Departments of MoHS, MOHS at various levels, and key stakeholders. The Three Millennium Development Goal Fund (3MDG Fund) The 3MDG Fund is a multi-donor trust fund funded by Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and USA, and operated by United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS). -

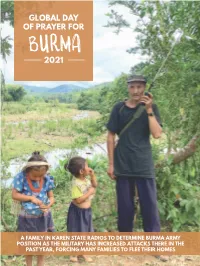

Global Day of Prayer for 2021

GLOBAL DAY OFBURMA PRAYER FOR 2021 A FAMILY IN KAREN STATE RADIOS TO DETERMINE BURMA ARMY POSITION AS THE MILITARY HAS INCREASED ATTACKS THERE IN THE PAST YEAR, FORCING MANY FAMILIES TO FLEE THEIR HOMES From the Director Dear friends, Th ank you for your prayers and love for the people of Burma. Burma has now faced over 70 years of civil war, death, displacement, injustice and sorrow. But we don’t give up praying because God while at the same time preventing over one million 1 has not given up and we see in our own lives how Muslim Rohingya from the same state from God answers prayer and does the impossible. returning. Th e Rohingya were attacked in 2017 and We are told by Jesus to be persistent in prayer, forced to fl ee to refugee camps in Bangladesh where not give up and pray that God‘s kingdom will come they live in squalor with very little likelihood of on earth as it is in heaven. Every time we pray and change. In northern Burma attacks against Kachin, we obey Jesus we feel His presence and we are part Shan and Ta’ang continue with over 100,000 of His kingdom on this earth regardless of the other displaced. In eastern Burma in Karen State there is kingdoms around us. a ceasefi re but it is regularly violated with the killing God works through prayer, fi rst to change of men, women and children. our own hearts and to guide us in what we are to Th ere was an election in November 2020 do, and then to bring change to others. -

Food Security Update - April 2014 Early Warning and Situation Reports

Food Security Update - April 2014 Early Warning and Situation Reports Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Purpose and Interpretation: Food Security Updates (FSUs) have two key components; 1) an Early Warning (EW) section and 2) a Situation Report (SitRep) from main States and Regions. The EW section outlines the key events occurring throughout Myanmar that are currently impacting the food security situation. By highlighting these events, it is possible to identify townships where food security status is likely to deteriorate in the short term, facilitating decision-making and response. Methodologically, WFP classifies the severity of shocks as Low, Moderate or High, depending on the likelihood that a shock is significant enough to result in deteriorations in key food security indicators as defined by the Food Security Information Network (FSIN). Indicator scores are then summed to determine a shock severity score. This methodology is summa- rized below. The SitRep, by contrast, provides general information on a monthly basis about the food security situation in key Regions and States in Myanmar. SitReps sum- marize the evolving food security situation and help provide context to more in-depth FSIN periodic monitoring rounds. Source of information: Information included in Food Security Updates (FSUs) comes from a variety of sources, including observations from field staff, information from assessment activities, community reports or requests for assistance, government requests for action and information from media outlets. Monthly Updates can be accessed online at http://www.fsinmyanmar.net. Early Warning Report: Key Shocks Reported in April Recent FSIN Shock Region/ classifica- Severity Shock Township severity 1 Direct effect and likely human impact State tions score Post Pre Across Magway region, water ponds have dried up and most villages have to purchase drink- Low Dry Spells Magway All townships 6 ing water at a cost of 200-250 MMK a barrel. -

Brief Background

Brief Background In 2007, the Burmese military government reached an agreement to provide electricity to Bangladesh through construction of a hydropower project comprising two large dams on the Lemro river in western Burma. The dams would be constructed by Datang Company of China: one above Ko Phe She village in Paletwa township, Chin state, and one near Sai Din village of Mrauk U township, Rakhine state. In 2009 the agreement with Bangladesh was withdrawn, but the project continued. Problems occurred from the outset of the project feasibility study, when Burma Army soldiers from Infantry Battalion 540 providing security for the Chinese surveyors, killed a cow owned by a villager of Ko Phe She village. Machinery was placed on the farmlands of Ko Phe She villagers, but no compensation was given. Workers from elsewhere were hired. No information about the project was provided to locals. When tensions worsened, the company submitted a complaint letter to the President of Burma, alleging falsely that local people were using violent means to oppose the projects. The District Police Officer even came to the site to investigate the complaint. Chin state Chief Minister U Hung Ngai also visited the site and carried out an investigation. Due to local opposition, the Burmese government suspended the project in 2014. However, they resumed it in July 2016, with the backing of France, which pledged US$ one million for the feasibility study. Surveying then continued by Belgian company Tractebel‐Engie, with findings submitted in a workshop held in Naypyidaw on 18 March, 2018. Local villagers reported that Tractebel‐Engie was continuing surveying in mid‐2019, despite fighting between the Arakan Army and the Burma Army near the planned dam sites. -

CRC Shadow Report Burma the Plight of Children Under Military Rule in Burma

CRC Shadow Report Burma The plight of children under military rule in Burma Child Rights Forum of Burma 29th April 2011 Assistance for All Political Prisoners-Burma (AAPP-B), Burma Issues ( BI), Back Pack Health Worker Team(BPHWT) and Emergency Action Team (EAT), Burma Anti-Child Trafficking (Burma-ACT), Burmese Migrant Workers Education Committee (BMWEC), Chin Human Rights Organization (CHRO), Committee For Protection and Promote of Child Rights-Burma (CPPCR-Burma), Foundation for Education and Development (FED)/Grassroots Human Rights Education (GHRE), Human Rights Education Institute of Burma (HREIB), Karen Human Rights Group (KHRG), Karen Youth Organization (KYO), Kachin Women’s Association Thailand (KWAT), Mae Tao Clinic (MTC), Oversea Mon Women’s Organization (OMWO), Social Action for Women (SAW),Women and Child Rights Project (WCRP) and Human Rights Foundation of Monland (HURFOM),Yoma 3 News Service (Burma) TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 Acknowledgement 3 Introduction 3 Purpose and Methodology of the Report 4 Articles 24 and 27 ‐ the right to health and an adequate standard of living 6 Access to Health Services 7 Child Malnutrition 8 Maternal health 9 Denial of the right to health for children in prisons 10 Article 28 – Right to education 13 Inadequate teacher salaries 14 Armed conflict and education 15 Education for girls 16 Discrimination in education 16 Human Rights Education 17 Article 32–Child Labour 19 Forced Labour 20 Portering for the Tatmadaw 21 Article 34 and 35 ‐ Trafficking in Children 23 Corruption and restrictions -

Myanmar EMMA Report FINAL

Emergency Market Mapping and Analysis (EMMA) Rice Market System Paletwa Township, Chin State, Myanmar Alan Moseley and Carol Ward International Rescue Committee May 29-June 9, 2012 1. Executive Summary In June 2012 the International Rescue Committee conducted an EMMA assessment of the rice market in Paletwa Township, southern Chin State. The EMMA was carried out within the framework of a program entitled “Building Community Resilience to Disaster Risk through Community Driven WASH and Livelihoods Projects,” funded by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). Unlike most EMMAs, which are conducted after an emergency and seek to understand how market systems have been affected by the crisis, the Myanmar EMMA was targeted at mapping a baseline market under normal conditions. IRC anticipated that a better understanding of the baseline market for rice, and target communities’ interactions with this market, would provide insights on how to improve their livelihoods and food security in times of stress. IRC also hoped that the EMMA would yield useful insights into how EMMA as a tool of assessment and analysis might be applied in a DRR context more generally. The EMMA focused on 35 villages in Paletwa Township, a remote and impoverished area on Myanmar’s western border. The EMMA’s key findings were as follows: The target communities produce rice but their production is insufficient to meet their consumption needs for 12 months a year. They are thus net consumers of rice, and typically face shortages in their home production for five months a year. To fill the gap, rice is purchased by target communities through a supply chain that originates in Kyauk Taw Township, and involves a system of market actors that includes Kyauk Taw growers and wholesalers, Paletwa village tract wholesalers and retailers, and village level small retailers. -

Myanmar Languages | Ethnologue

7/24/2016 Myanmar Languages | Ethnologue Myanmar LANGUAGES Akeu [aeu] Shan State, Kengtung and Mongla townships. 1,000 in Myanmar (2004 E. Johnson). Status: 5 (Developing). Alternate Names: Akheu, Aki, Akui. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Ngwi-Burmese, Ngwi, Southern. Comments: Non-indigenous. More Information Akha [ahk] Shan State, east Kengtung district. 200,000 in Myanmar (Bradley 2007a). Total users in all countries: 563,960. Status: 3 (Wider communication). Alternate Names: Ahka, Aini, Aka, Ak’a, Ekaw, Ikaw, Ikor, Kaw, Kha Ko, Khako, Khao Kha Ko, Ko, Yani. Dialects: Much dialectal variation; some do not understand each other. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Ngwi-Burmese, Ngwi, Southern. More Information Anal [anm] Sagaing: Tamu town, 10 households. 50 in Myanmar (2010). Status: 6b (Threatened). Alternate Names: Namfau. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Sal, Kuki-Chin-Naga, Kuki-Chin, Northern. Comments: Non- indigenous. Christian. More Information Anong [nun] Northern Kachin State, mainly Kawnglangphu township. 400 in Myanmar (2000 D. Bradley), decreasing. Ethnic population: 10,000 (Bradley 2007b). Total users in all countries: 450. Status: 7 (Shifting). Alternate Names: Anoong, Anu, Anung, Fuchve, Fuch’ye, Khingpang, Kwingsang, Kwinp’ang, Naw, Nawpha, Nu. Dialects: Slightly di㨽erent dialects of Anong spoken in China and Myanmar, although no reported diഡculty communicating with each other. Low inherent intelligibility with the Matwang variety of Rawang [raw]. Lexical similarity: 87%–89% with Anong in Myanmar and Anong in China, 73%–76% with T’rung [duu], 77%–83% with Matwang variety of Rawang [raw]. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Central Tibeto-Burman, Nungish. Comments: Di㨽erent from Nung (Tai family) of Viet Nam, Laos, and China, and from Chinese Nung (Cantonese) of Viet Nam.