Tesis Doctoral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rutas De Autobuses Curso 2020-2021

RUTAS DE AUTOBUSES CURSO 2020-2021 RECORRIDOS DE LA MAÑANA* RUTA Nº 0 - BARAKALDO SANTURTZI Landeta 7:45 Murrieta 7:52 S. Juan de Dios 7:55 PORTUGALETE Abaro10. 8:00 BARAKALDO Urban 8:09 Bagatza (Beurko Berria) 8:15 Palacio de Justicia 8:20 B.E.C. 8:25 RUTA Nº1 - BILBAO ELCANO Parada autobús Elcano 16 7:50 ALAMEDA URKIJO Cines Mikeldi 7:55 Mª DÍAZ DE HARO Jesuitas 7:57 LA CASILLA La Casilla // Eguren 8:03 LARRASKITU Polideportivo 8:10 MIRIBILLA Frente entrada tren 8;15 RUTA Nº 2 – ALGORTA GETXO (PEÑAS STA MARINA)/ANDRAMARI Parada Bizkaibus 8:00 LA VENTA 8:12 AVDA. DEL ANGEL Parada autobús 8:14 SAN MARTIN Parada autobús (Antiguo Gimnasio) 8:15 TRINITARIOS Parada autobús 8:18 TELEPIZZA 8:22 SANITAS Dirección Bilbao 8:30 LANDABARRI Frente a Quebec 8:35 *Tanto las rutas como los horarios son susceptibles de modificaciones RUTA Nº 3 – BILBAO SAN IGNACIO Lehendakari Aguirre 179// 131 7:50/ / 7:55 GRAN VÍA Renault 8:07 GRAN VÍA Gran Vía 41. ( Álvaro Moreno) 8:13 LEIOA Frente al Conservatorio 8:30 RUTA Nº 4 – BILBAO DURANGO Arriluzea 7:20 AMOREBIETA Ambulatorio 7:35 GALDAKANO Carretera General 634.( Barrio Aperribai) 7:52 CAMPO VOLANTIN La Salve 8:10 ZUBIARTE Centro Comercial 8:15 PLAZA EUSKADI Museo Bellas Artes PLAZA ENSANCHE Edificio MAPFRE 8:25 ALAMEDA REKALDE Frente Escolapios 8:27 RUTA Nº 5 – NEGURI ESTACIÓN DE NEGURI Cantina 8:20 ROTONDA REGOYOS Gasolinera Neguri S. IGNACIO (ALGORTA) Dirección Algorta 8:25 CASINO DE ALGORTA Antigua gasolinera 8:30 RUTA Nº 6- PLENTZIA-AIBOA PLENTZIA Rotonda Gandía 7:42 ABANICO PLENTZIA 7:52 URDULIZ Estación Metro. -

Urban Sprawl UITP : If We Divide Density ( Hab/Sq Km) by 3, Then

London, 20st September 2007 Instituto de Estudios Territoriales de Bizkaia Diputación Foral de Bizkaia (Bizkaia County Council) Created in 1987 -Land Planning -Transport -Urban planning… Bizkaia 1.140.026 inhab. 111 municipalities.(92<10.000h.) 2.117 Km2. 538,52 hab/Km2 Bilbao: 367.929 inhb. Metropolitan Bilbao 1 mill. inhab ( aprox) 1.771 inhab/km2 Bizkaia -Services, third sector -Bancs (BBVA) -Electricity (Iberdrola) -Port of Bilbao:29 mill Tm./año -ACB, Arcelor new generation steel factory -Technology Park -European Software Institute -Bilbao Exhibition Centre -Airport: 4 mill. de pax/year. What is sustainability? Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs Sustainability: Basic principles -intergenerational equity: we haven´t inherited our father´s world but rented our children´s. -intragenerational equity: social justice, all people currently alive have an equal right to benefit from the use of resources. -transfrontier responsibility:sustainibility in one region cannot be achieved at the expense of environmental conditions elsewhere. Basic principles -the public trust doctrine: places a duty on the estate to hold environmental resources in trust for the benefit of the public. -precautionary principle:lack of full certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponning cost effective measures to prevent environmental degradation. Basic principles -subsidiarity principle: decissions should be made by the communities affected,or, on their behalf, by the -

The Vision of a Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao

HARVARD DESIGN SCHOOL THE VISION OF A GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM IN BILBAO In a March 31, 1999 article, the Washington Post? posed the following question: "Can a single building bring a whole city back to life? More precisely, can a single modern building designed for an abandoned shipyard by a laid-back California architect breath new economic and cultural life into a decaying industri- al city in the Spanish rust belt?" Still, the issues addressed by the article illustrate only a small part of the multifaceted Guggenheim Museum of Bilbao. A thorough study of how this building was conceived and made reveals equally significant aspects such as getting the best from the design architect, the master handling of the project by an inexperienced owner, the pivotal role of the executive architect-project man- ager, the dependence on local expertise for construction, the transformation of the architectural profession by information technology, the budgeting and scheduling of an unprecedented project without sufficient information. By studying these issues, the greater question can be asked: "Can the success of the Guggenheim museum be repeated?" 1 Museum Puts Bilbao Back on Spain’s Economic and Cultural Maps T.R. Reid; The Washington Post; Mar 31, 1999; pg. A.16 Graduate student Stefanos Skylakakis prepared this case under the supervision of Professor Spiro N. Pollalis as the basis for class discussion rather to illustrate effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation, a design process or a design itself. Copyright © 2005 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. To order copies or request permission to repro- duce materials call (617) 495-4496. -

Core Indicators of Public Funding and Expenditure on Culture

Core indicators of public funding and expenditure on culture DECEMBER 2018 KULTURA ETA HIZKUNTZA POLITIKA SAILA DEPARTAMENTO DE CULTURA Y POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA contents 1. Cultural vitality 3 • Cultural expenditure per inhabitant 3 • Cultural effort 4 • GDP/Culture 4 2. Expenditure diversification 5 • Expenditure diversification by sector 5 • Diversification of expenditure by territorial concentration 7 • Expenditure diversification by administrative grouping of municipalities 8 • Driving force city councils 9 3. Decentralisation of expenditure 11 • Expenditure decentralisation ratio 11 • Employment decentralisation ratio 11 4. Expenditure structure 12 • Fixed expenditure structur 12 • Subsidy ratio 14 • Revenue structure 15 5. Public employment in culture 16 • Public employment in culture ratio 16 6. Cultural revenue 17 • Self-financing of autonomous organisations, foundations and public companies 17 • Municipal dependency ratio 17 7. Gender 18 • Employment segregation by sex 18 • Glass ceiling in cultural public employment 18 Methodological notes 19 2 1. Cultural vitality n Cultural expenditure per inhabitant Measures the expenditure on culture carried out by the different levels of government per inhabitant. Government level Consolidated expenditure Population €/inhabitant Basque Government 73.386.970 33,8 Regional Governments 87.555.713 2.171.886 40,3 City Councils 282.880.847 130,2 Territory Integrated expenditure* Population €/inhabitant Total 282.880.847 2.171.886 130,2 Araba / Álava 26.694.139 322.335 82,8 Arabako Ibarrak / Alava -

Citizens in Greater Bilbao Regard the Services of the Green Belt Ecosystems As Highly Beneficial 20 August 2013

Citizens in Greater Bilbao regard the services of the Green Belt ecosystems as highly beneficial 20 August 2013 "There are mountains, forests, reservoirs, rivers and streams, beaches, marshes and dunes, cliffs and scrubland," they point out. But how do citizens rate the services offered by these ecosystems? To find out, the researchers drew up a questionnaire comprising 30 questions, and interviewed 500 people. In view of the responses, nearly all the respondents are aware that ecosystems provide services and they value and appreciate them. However, even though nearly 80% of the respondents identified the cultural services (leisure, landscape, tranquillity, etc.), only a third of them identified the regulating Izaskun Casado, is a member of the research group into services, and even fewer (1.8%) identified the Landscape, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the supply services. UPV/EHU-University of the Basque Country, and author of the work. Credit: UPV/EHU The survey also highlighted the fact that the most highly rated services are the improvement in air quality and biodiversity conservation. By contrast, most of the respondents (88%) are prepared to According to Izaskun Casado-Arzuaga, collaborate in preserving the area. The ecosystems provide more services than what many socioeconomic characteristics that exert a positive people believe. And their value is not in fact limited influence on this decision are, among others, being to the possibilities they offer in terms of landscape, from an urban background, being young, visiting aesthetic aspects or leisure. Casado is one of the the protected areas and being a woman. members of the research group into Landscape, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services and, in her Citizen participation is needed opinion, it is important to remember the other services offered by ecosystems. -

The Bay of Bizkaia Plentzia Aizkorri / La Salvaje / Gorrondatxe Aixerrota Sopela Barinatxe Windmill Ibarbengoa Bidezabal

SAN JUAN DE GAZTELUGATXE THE BAY OF BIZKAIA PLENTZIA AIZKORRI / LA SALVAJE / GORRONDATXE AIXERROTA SOPELA BARINATXE WINDMILL IBARBENGOA BIDEZABAL ALGORTA CARRETERA A LA GALEA FISHERMEN´S AIBOA GUILD BIZKAIA NEGURI i GETXO BRIDGE BILBAO GOBELA AIRPORT AREETA i 34 SANTURTZI P KABIEZES PEÑOTA Line 2 Line 1 PORTUGALETE ABATXOLO BILBAO THE SALAZAR TOWER ANSIO ZIENTOETXE BEC CASCO VIEJO BILBAO EXHIBITION CENTRE SAN MAMÉS P E INDAUTXU Ñ ABANDO A MOYUA D E GUGGENHEIM BILBAO S A TXE N ZIENTOE TA M A R IN A M AR T IT U R R I GABRIEL RAMOS URANGA N A G P A CARRETERA A LA GALEA GUST D I A M 32 A M VO ADOLFO BÉCQUER RI A UR R TIT T R I A T M U R R L I E THE BAY OF BIZKAIA 4 G N . A 33 DA AV GOÑI IBARBENGOA A VDA. ANGEL A ARRIGUNAGA ORMAZA A MARÍA AIXERROT PLENTZIA-SOPELACR. SANT A FERRY VDA. ANGEL B ALTUBE A ALTUBE J N BIDEZABAL A A D G A TA BIDEZABAL D AR ANDENE E L A R R GETXO IG U N A BILBAO G SANTANDER A OLLARRETXE TELLETXE M U E L L E D E A L G TA O 7 T R 27 E P L T AVDA. ALGOR A RETXONDO L AVDA. DE SALSIDU A E HARRA ZA U T T X R VDA. DE SALSIDU E A PO IDAD ZIERBENA 26 AR C 31 E ALGORTA 25 EN 29 RR TO 28 T 3 M U E L AMEZTI TELLETXE L E D HERRIA E E R E A 12 G P A ASEO SARDINERA EUSKAL 22 ILUNBE A URIMENDI S T P O P EREAGA P 21 MONTAÑO O 30 i H C 2 3 MENDIGANE E S U S O 23 VDA. -

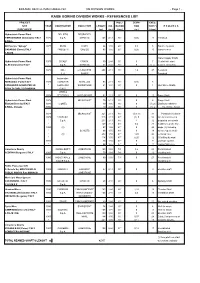

Raise Boring Division Works - References List

EDILMAC DEI F.LLI MACCABELLI Srl RB DIVISION WORKS - Page 1 - RAISE BORING DIVISION WORKS - REFERENCES LIST PROJECT INCLI- DEVIA- EXEC. SITE YEAR CONTRACTOR ROCK TYPE LENGHT DIA. NATION TION TIME (*) R E M A R K S PURCHASER (m.) (m.) (deg.) (m.) (days) Hydroeletric Power Plant DE LIETO DEGRADED TIMPAGRANDE (Catanzaro) ITALY 1976 S.p.A. GRANITE 124 2,13 90° 0,05 14 Penstock E.N.E.L. Oil Pipeline "Spluga" 1977 SNAM HARD 84 1,55 60° 0,3 5 Pipeline by-pass CASARGO (Como) ITALY " PROGETTI GNEISS 93 1,55 60° 0,25 10 Varrone river S.N.A.M. Water Supply Shafts Hydroeletric Power Plant 1977 SICALF CRACK 59 2,44 90° 0 7 (°) pilot hole start ALBI (Catanzaro) ITALY " S.p.A. GRANITE 21 2,44 90° 0 (°) 4 to 45 m. deep.into 1978 SELI with QUARTZ. 208 2,13 90° 1,2 47 Penstock S.r.l. BANKS Penstock Hydroeletric Power Plant Association RIDRACOLI (Forlì) ITALY 1978 COGEFAR MARL and 93 2,13 90° 0,06 8 CONSORZIO ACQUE PER LE " LODIGIANI SANDSTONE 61 1,84 90° 0 4 Inlet Sluice Shafts PROV.DI FORLI' E RAVENNA C.M.C. CHINI & 1978 TEDESCHI HARD SCHIST 91 2,13 90° 0 13 Surge Shaft Hydroeletric Power Plant 1978 MICASCHIST 70 2,13 90° 0 8 Surge Shaft EDOLO (Brescia) ITALY 1981 ICOMEC 40 3,05 36° 0 (1) 25 Distributor Shaft 4x E.N.E.L. Venezia 1980 10 2,44 90° 0 (1) 2 10- (1) time for all 1978 MICASCHIST 321 2,13 46° (1) 8,75 37 Penstock (1) devia- 1979 FARSURA 313 2,13 47° (2) 0 56 tion for crossover in " S.p.A. -

Cocheras De Kabiezes Del Ferrocarril Metropolitano De Bilbao Estudio

COCHERAS DE KABIEZES DEL FERROCARRIL METROPOLITANO DE BILBAO ESTUDIO INFORMATIVO - MEMORIA - P210E38-SR-EI- ME001 Mayo, 2012 SENER Ingeniería y Sistemas S.A. - Getxo 2012 La información facilitada en este documento es confidencial y de uso restringido, pudiendo ser utilizada, única y exclusivamente, a los efectos objeto del mismo. Queda terminantemente prohibida la modificación, explotación, reproducción, comunicación a terceros o distribución de la totalidad o parte de los contenidos del mismo sin el consentimiento expreso y por escrito de SENER Ingeniería y Sistemas, S.A. En ningún caso la no contestación a la correspondiente solicitud, podrá ser entendida como autorización presunta para su utilización. ESTUDIO INFORMATIVO DE LAS P210E38-SR-EI-ME001-3.0 COCHERAS DE KABIEZES - METRO DE BILBAO Mayo, 2012 Memoria Pág. 2 de 30 TÍTULO DEL DOCUMENTO: ESTUDIO INFORMATIVO DE LAS COCHERAS DE KABIEZES. METRO DE BILBAO MEMORIA DOCUMENTO : P210E38-SR-EI-ME 001 Referencia : P210E38 Fichero : P210E38-EI-ME001_Rev3.doc Revisión número: 4 Fecha revisión : Mayo, 2014 Nombre Firma Fecha Realizado por C. Baleia Azinhaga Mayo 2012 Revisado J. Borrego Olavarri Mayo 2012 Aprobado M. Ugarte Balles Mayo 2012 SENER Ingeniería y Sistemas S.A. - Getxo 2012 La información facilitada en este documento es confidencial y de uso restringido, pudiendo ser utilizada, única y exclusivamente, a los efectos objeto del mismo. Queda terminantemente prohibida la modificación, explotación, reproducción, comunicación a terceros o distribución de la totalidad o parte de los contenidos del mismo sin el consentimiento expreso y por escrito de SENER Ingeniería y Sistemas, S.A. En ningún caso la no contestación a la correspondiente solicitud, podrá ser entendida como autorización presunta para su utilización. -

Rigid Catenary March 2021

SECTOR REFERENCE LIST Rigid Catenary March 2021 Project Name Location Date Length Voltage Design (km) Speed (km/h) Metro Buenos Aires Line B Alem-Rosas Argentina 2014 25 600 V 90 Metro Buenos Aires Line E Bolívar-Retiro Argentina 2018 4 1,5 kV 90 Perth- Forestfield Airport link Australia 2019 15 25 kV 140 Melbourne Metro Rail Project Australia Design 1 1,5 kV 90 ÖBB Marchtrent-Traun Austria 1993 0.5 15 - SNCV Charleroi Belgium 1992 0.7 750 V 80 STIB Schaerbeek Depot Brussels Belgium 1998 0.77 750 V 20 STIB Rogier Tunnel Brussels Belgium 2008 0.5 750 V 80 STIB Haren Depot Belgium 2008 3 750 V 20 STIB Thomas Tunnel Brussels Belgium 2009 0.1 750 V 20 STIB Marconi depot Belgium 2016 5 750 V 20 STIB Simonis Belgium 2017 3.1 750 V 20 INFRABEL Tunnel Saint Martin Liege Belgium 2019 1.35 3 kV 80 INFRABEL Tunnel Pierreuse Belgium 2020 3.2 3 kV 80 Metro Sao Paulo Line 4 Brazil 2010 28 1.5 kV 110 Metro Sao Paulo Line 5 phase 1 Brazil 2013 2.3 1.5 kV 100 Metro Sao Paulo Line 5 phase 2 Brazil 2018 21 1.5 kV 100 Metro Sao Paulo Line 4 Extension Brazil 2021 4.5 1.5 kV 110 Metro Sofia Line 3 Bulgaria 2018-2019 23.04 1.5 kV 90 Toronto Saint Clair station Canada 2016 0.37 750 V 30 Ottawa Confederation Line Canada 2018 7.88 1.5 kV 90 Metro Santiago de Chine L3 & 6 Chile 2016 79.75 1.5 kV 80 Guangzhou China 1999 0.2 1.5 kV - MTR Hong Kong SIL-KTE China 2015 12 1.5 kV 90 MTR Hong Kong SCL China 2017 25 25 kV 130 March 2021 © Pandrol 2021 1 of 6 Rigid Catenary Helsinki-Vantaa Airport Finland 2012 16 25 kV 120 RATP Défense/Nation RER A France 1983 0.4 1.5 kV -

THE BASQUE COUNTRY a Varied and San Sebastián Seductive Region

1 Bilbao San Sebastián Vitoria-Gasteiz All of the TOP experiences detailed in TOP in this catalogue are subject to change and EXPE may be updated. Therefore, we advise you RIEN to check the website for the most up to date CE prices before you book your trip. www.basquecountrytourism.net 22 14 32 40 City break getaways 6 6 Bilbao 14 San Sebastián 22 Vitoria-Gasteiz 32 Gastronomy 40 Wine Tourism 44 50 44 The Basque Coast 50 Active Nature 56 Culture 60 Unmissable experiences 56 62 Practical information Bilbao San Sebastián Vitoria- Gasteiz 4 THE BASQUE COUNTRY a varied and San Sebastián seductive region You are about to embark on an adventure If you explore the history of the figures with many attractions: a varied landscape, who have marked the personality of these a mild climate, ancient culture, renowned communities, you will discover how their gastronomy... These are the nuances maritime, industrial and agricultural that make the Basque Country a tourist character, always diverse and enterprising, destination you will be delighted to has been bred. discover. And if you find the coastal and inland Two colours will accompany you on your villages interesting, you will be fascinated journey through the Basque Country: the by the three capitals. Bilbao will surprise green of the mountains and valleys, and you with its transformation from the blue of the sea. an industrial city to an avant garde metropolis, that brings together the You will discover that the Basque people world's best architects. San Sebastián, maintain strong links with the natural exquisite and unique, will seduce you with resources of the land and the sea. -

Themed Tours Spain & Portugal

Getxo Beach (Greater Bilbao) Themed Tours Spain & Portugal Wonders of Northern Spain (Basque Country & Rioja Alavesa) Bilbao - Basque Coast - San Sebastián - Vitoria - Rioja Alavesa 6 days / 5 nights The tour includes Arrival to Bilbao: Thursdays 4 Private transfers, Bilbao Airport/railway station - hotel - Bilbao Airport/railway station. 4 Overnight accommodation with Buffet Breakfast, 5 nights in Bilbao at the chosen hotel category or similar. 5 4 Day trips on Regular basis: from Bilbao around the Basque country & La Rioja Alavesa as per program. Bilbao Introducing the tour SPAIN With this exciting tour you will discover Spain’s green Basque Country, including locations in southern France and the wine region of Rioja Alavesa. Starting from Bilbao, with its famous Guggenheim Museum you will visit the idilic green basque coast including the elegant city of San Sebastian, as well as, Biarritz and Hendaya in France. Then you will discover Vitoria, the Basque country capital, and the monumental medieval village of Laguardia with magnificent wineries. You will enjoy wine tasting and tour of traditional wine cellars. At Elciego, the amazing architectural work of Frank Gehry at Marques de Riscal Wine Cellar is waiting at the end. Day 1 | Origin - Bilbao (Thursdays) pintxos in one of the many taverns or noon, return to hotel and free time to Day 5 | Bilbao - Vitoria - Rioja Upon arrival to Bilbao Airport our driver cafés lining the streets. Option: Pint- stroll around the city on your own pace. Alavesa (Labastida - will greet you and then transfer to the xos Route as lunch or dinner including: 8 Overnight in Bilbao. -

Industrial Culturescape: Territory As Context

Sustainable Tourism VIII 237 INDUSTRIAL CULTURESCAPE: TERRITORY AS CONTEXT ANA SCHMIDT Provincial Government of Biscay, Spain National University of Distance Education (UNED), Spain ABSTRACT The European Landscape Convention has contributed to understanding landscape as an important component of collective well-being and highlighted the need to manage the entire territory as a landscape. The Nervion estuary, Abra Bay and mining area deserve to be considered an urban cultural landscape, because of their heritage value and singular beauty. The landscape of the Nervion and Abra has developed over time, above all, throughout the period of industrialisation. Restoring the industrial heritage landscape, such as the old mining railways, may bring the existing cultural landscape closer to the environment of the people who live in these areas. This study categorises the heritage elements and traces of the Orconera mining railway, in order to understand the current landscape and determine a proposal for action to preserve them and restore the mining railway line as a green infrastructure. In this case, preservation as a sustainable landscape means proposing a new use for it as cultural landscape and tourism. Although industrialisation has had a serious impact on the development of the whole Bilbao metropolitan area, the mining-industrial heritage includes sites that are somewhat unexplored and overlooked by urban policies. Keywords: cultural landscape, cultural tourism, industrial cultural heritage, industrial tourism, mining railways. 1 INTRODUCTION In the study we carried out on the Nervion Estuary, its banks, the Abra Bay and the mining area within the Greater Metropolitan Area of Bilbao, we found a landscape that rightfully comes under the description of cultural landscape, as per this definition in the 1992 UNESCO Convention on Cultural and Natural Heritage.