BC's Faith-Based Postsecondary Institutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Session Meeting Agenda

Board of Governors Open Session Agenda Pkg - Nov. 24, 2020 Page 1 of 124 Board of Governors Open Session Meeting Agenda Tuesday, November 24, 2020 Meetings to be held via the Zoom Conference System (www.zoom.us) 9:00am-9:10am • To join the meeting, click HERE • Meeting ID: 650 5160 5949 • To join by phone dial: 1-778-907-2071 (Vancouver) and use meeting ID: 650 5160 5949# **please note that long distance charges may apply 10:35am-12:00pm • To join the meeting, click HERE • Meeting ID: 691 2777 3815 • To join by phone dial: 1-778-907-2071 (Vancouver) and use meeting ID: 691 2777 3815# **please note that long distance charges will apply We respectfully acknowledge that we are meeting on the unceded traditional lands of the Indigenous people who have inhabited and used the lands since time immemorial. Related Time Pages APPROVAL OF AGENDA Recommended Motion: 9:00am “BE IT RESOLVED THAT the November 24, 2020, Okanagan College Board of Governors Open session meeting agenda is approved.” INTRODUCTION OF NEW MEMBERS 9:05am OATH OF OFFICE DECLARATION OF CONFLICT CONSENT AGENDA 10:35am Recommended Motion: “BE IT RESOLVED THAT the Consent Agenda be approved as presented.” Previous Minutes – September 29, 2020 6-9 Written Reports 5.2.1. President’s Report (J. Hamilton) 10-11 Board of Governors Open Session Agenda Pkg - Nov. 24, 2020 Page 2 of 124 Related Time Pages Approvals 5.3.1. Board Observers Recommended Motion: “BE IT RESOLVED that the be following persons be appointed as Board Observers for a one-year term from November 24, 2020 to November 23, 2021: Sharon Mansiere, representing Okanagan College Faculty Association (OCFA), Cam McRobb, representing BCGEU Vocational Instructors, Paula Faragher, representing BCGEU Support Staff, Inga Wheeler, representing Okanagan College Admin. -

SCHEDULE B – RECOGNIZED PRACTICAL NURSING EDUCATION PROGRAMS (Sections 88, 91, 93) ______

SCHEDULE B – RECOGNIZED PRACTICAL NURSING EDUCATION PROGRAMS (Sections 88, 91, 93) ___________ Educational Institution Campus Program Type Camosun College Victoria Generic CDI College Richmond Generic CDI College Surrey Generic Coast Mountain College Terrace Access College of New Caledonia Burns Lake Generic College of New Caledonia Prince George Generic College of the Rockies Cranbrook Generic Discovery Community College Campbell River Generic & Access Discovery Community College Nanaimo Generic & Access Nicola Valley Institute of Technology Merritt Access North Island College Campbell River Generic North Island College Port Alberni Generic Northern Lights College Dawson Creek Generic Okanagan College Kelowna Generic Okanagan College Penticton Generic Okanagan College Salmon Arm Generic Okanagan College Vernon Generic Sprott Shaw College Abbotsford Generic Sprott Shaw College Downtown Vancouver Generic & Access Sprott Shaw College East Vancouver Generic & Access Educational Institution Campus Program Type Sprott Shaw College Kamloops Generic & Access Sprott Shaw College Kelowna Generic & Access Sprott Shaw College New Westminster Generic & Access Sprott Shaw College Penticton Generic & Access Sprott Shaw College Surrey Generic Sprott Shaw College Victoria Generic Stenberg College Surrey Generic Thompson Rivers University Williams Lake Generic University of the Fraser Valley Chilliwack Generic Vancouver Career College Abbotsford Generic Vancouver Career College Burnaby Generic Vancouver Community College Vancouver (Broadway) Generic & -

Rev. Raymond C. Aldred

Rev. Raymond C. Aldred Assistant Professor of Theology Ambrose Seminary/Ambrose University Ministry Trainer/Director My People International Board Chair Indigenous Pathways Address 1168 Berkley Drive NW Calgary, AB T3K 1S7 Home: 403-475-3994 Fax: 403-571-2556 Cellular: 403-771-1187 Email: [email protected] Personal` Born January 23, 1960, in Grande Prairie, AB Treaty 8 First Nation Person Married to Elaine Aldred; two daughters, two sons Skills Class 3 Alberta Driver’s License Indigenous Story Teller Author On-line course development and delivery Interests Hunting and Fishing Run 15-20 miles per week Traditional Indigenous music and dance 1 Education Wycliffe College at TST ThD program in progress London School of Theology Ph.D. program September 2004 – October 2013 unfinished Canadian Theology Seminary M.Div. highest honours, 2000 Canadian Bible College B.TH. highest honours, 1992 Employment Assistant Professor of Theology Ambrose Seminary/Ambrose University 2007-present My People International: Family Programs 2004-present Facilitate training of aboriginal leaders Adjunct Professor, North American Institute for Indigenous Theological Studies: Theology 2011-Present Circle Drive Alliance Church Aboriginal Consultant, November 2012-Present Rocky Mountain Bible College Fall 2013, Fall 2010 Adjunct professor Canadian aboriginal cultures Visiting Professor July 2014, July, 2006, 2014 Vancouver School of Theology: Native Consortium, Vancouver, BC Adjunct Professor August, 2005 William Catherine Booth College, Winnipeg, MB Adjunct Professor -

The Gospel and Globalization

the Gospel and Globalization Exploring the Religious Roots of a Globalized World Edited by Michael W. Goheen Erin G. Glanville Regent College Press • Geneva Society Vancouver, B.C., Canada THE GOSPEL AND GLOBALIZATION: EXPLORING THE RELIGIOUS ROOTS OF A GLOBALIZED WORLD Copyright © 2009 Regent College Publishing All rights reserved. Published 2009 by REGENT COLLEGE PUBLISHING 5800 University Boulevard / Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 2E4 / Canada / www.regentpublishing.com with GENEVA SOCIETY www.genevasociety.org Cover image by Ben Goheen Typeset by Dan Postma No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher or the Copyright Licensing Agency. Views expressed in works published by Regent College Publishing are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of Regent College (www.regent-college.edu). Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication The Gospel and globalization : exploring the religious roots of a globalized world / edited by Michael W. Goheen and Erin G. Glanville. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-57383-440-7 1. Globalization—Religious aspects—Christianity. 2. Globalization— Religious aspects—Islam. 3. Capitalism—Religious aspects—Christianity. 4. Capitalism—Religious aspects—Islam. 5. Globalization—Moral and ethical aspects. 6. Globalization—Economic aspects. 7. Christian ethics. 8. World politics. I. Goheen, Michael W., 1955- II. Glanville, Erin G., 1980- BL65.G55G68 2009 201’.7 C2009-902767-4 For Phoebe Shalom, because the future is secure Table of Contents Preface 7 Introduction 11 Michael W. Goheen and Erin G. -

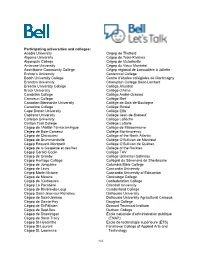

Participating Universities and Colleges: Acadia University Algoma University Algonquin College Ambrose University Assiniboine C

Participating universities and colleges: Acadia University Cégep de Thetford Algoma University Cégep de Trois-Rivières Algonquin College Cégep de Victoriaville Ambrose University Cégep du Vieux Montréal Assiniboine Community College Cégep régional de Lanaudière à Joliette Bishop’s University Centennial College Booth University College Centre d'études collégiales de Montmagny Brandon University Champlain College Saint-Lambert Brescia University College Collège Ahuntsic Brock University Collège d’Alma Cambrian College Collège André-Grasset Camosun College Collège Bart Canadian Mennonite University Collège de Bois-de-Boulogne Canadore College Collège Boréal Cape Breton University Collège Ellis Capilano University Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf Carleton University Collège Laflèche Carlton Trail College Collège LaSalle Cégep de l’Abitibi-Témiscamingue Collège de Maisonneuve Cégep de Baie-Comeau Collège Montmorency Cégep de Chicoutimi College of the North Atlantic Cégep de Drummondville Collège O’Sullivan de Montréal Cégep Édouard-Montpetit Collège O’Sullivan de Québec Cégep de la Gaspésie et des Îles College of the Rockies Cégep Gérald-Godin Collège TAV Cégep de Granby Collège Universel Gatineau Cégep Heritage College Collégial du Séminaire de Sherbrooke Cégep de Jonquière Columbia Bible College Cégep de Lévis Concordia University Cégep Marie-Victorin Concordia University of Edmonton Cégep de Matane Conestoga College Cégep de l’Outaouais Confederation College Cégep La Pocatière Crandall University Cégep de Rivière-du-Loup Cumberland College Cégep Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu Dalhousie University Cégep de Saint-Jérôme Dalhousie University Agricultural Campus Cégep de Sainte-Foy Douglas College Cégep de St-Félicien Dumont Technical Institute Cégep de Sept-Îles Durham College Cégep de Shawinigan École nationale d’administration publique Cégep de Sorel-Tracy (ENAP) Cégep St-Hyacinthe École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS) Cégep St-Laurent Fanshawe College of Applied Arts and Cégep St. -

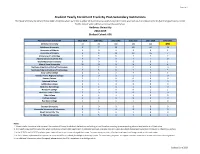

Student Yearly Enrolment Track by Post-Secondary Institutions

Page 1 of 1 Student Yearly Enrolment Track By Post-Secondary Institutions The Student Yearly Enrolment Track table identifies where were the number of students in an institution (cohort size) who had valid enrolment records (full time/part time) in LERS for the cohort year and five years prior by institution. Ambrose University 2018-2019 Student Cohort: 696 Post-Secondary Institution 2013-2014 2014-2015 2015-2016 2016-2017 2017-2018 2018-2019 Ambrose University 33 83 180 284 421 696 Athabasca University Athabasca University 4 7 13 18 26 39 University of Alberta University of Alberta 3 0 2 0 0 2 University of Calgary University of Calgary 6 8 10 12 16 7 University of LethbridgeUniversity of Lethbridge 3 3 6 7 3 2 Alberta University ofAlberta the Arts University of the Arts 4 4 3 2 1 0 Grant MacEwan UniversityGrant MacEwan University 0 0 0 0 0 1 Mount Royal UniversityMount Royal University 10 12 8 9 6 4 Northern AlbertaNorthern Institute Alberta of Technology Institute of Technology 2 2 0 0 0 0 Southern AlbertaSouthern Institute Alberta of Technology Institute of Technology 9 6 6 7 2 3 Bow Valley College Bow Valley College 1 1 3 4 7 5 Grande Prairie RegionalGrande College Prairie Regional College 1 0 2 1 1 0 Keyano College Keyano College 1 1 0 0 0 0 Lakeland College Lakeland College 0 1 0 0 0 0 Lethbridge College Lethbridge College 0 1 0 0 0 0 Medicine Hat College Medicine Hat College 1 2 0 1 0 0 NorQuest College NorQuest College 0 0 0 0 1 1 Northern Lakes CollegeNorthern Lakes College 0 0 0 0 0 0 Olds College Olds College 1 1 1 1 0 0 Portage College Portage College 0 0 0 0 0 0 Red Deer College Red Deer College 0 1 1 1 2 0 Ambrose University - - - - - - - Burman University Burman University 0 0 0 0 0 0 Concordia UniversityConcordia of Edmonton University of Edmonton 0 0 0 0 0 0 King's University, The King's University, The 1 1 4 2 0 0 St. -

Making Connections Forging Links to Opportunity, Careers, Vision and Faith at Ambrose

SPRING 2017 THE MAGAZINE OF AMBROSE UNIVERSITY Making Connections Forging links to opportunity, careers, vision and faith at Ambrose It takes a village | The art of Christianity | Something fishy | Rethinking holiness Use your power for good. Make the switch today. Switch your electricity or natural gas at home or work to Sponsor Energy and fund the Canadian Poverty Institute (CPI) at Ambrose University. • Get the same price or better than your current provider • Cancel at any time without penalty • 50% of the profit on your energy use goes to the CPI Help us prevent and eradicate poverty by switching to Sponsor Energy today. It’s easy and makes a difference at no cost to you or your business. We believe it’s Sponsor possible to make Energy is money and make a difference. Half of our profit goes to a charity based on a of your choice — at no extra cost. simple idea: We’re part of a growing movement by industry to do more and to do better. To do good. A movement that empowers people to take small actions individually can have a big impact sponsorenergy.com collectively. All it takes is a few minutes of your time. 1-855-545-1160ambrose university 6 It takes a village Answering the question of poverty in Canada requires ideas and inspiration from across the nation. The new and innovative Poverty Studies Summer Institute brings passion and minds together. 8 8 Spotlight: Connecting and courts Dr. Monetta Bailey’s research shows how Canada’s anthem commitment to multiculturalism needs to extend into to the youth justice system — to keep more immigrant youth out of court. -

Faith Reason Justice SPIRIT

Spring/Summer 2014 faith reason justice SPIRIT The Magazine of EASTERN UNIVERSITY Spring/Summer 2014 Spirit is published by the Communications Office Eastern University 1300 Eagle Road St. Davids, PA 19087 610.341.5930 — Linda A. Olson ’96 M.Ed. Executive Director Patti Singleton Inside This Issue Art Director Staff Photographer Jason James THE INAUGURATION AND INSTALLATION Graphic Designer and Public Relations Assistant OF ROBERT G. DUFFETT......................................................1 Elyse Garner ’13 Writer/Social Media Coordinator ACADEMICS...................................................................................6 — FAITH AND PRACTICE..............................................................17 Article suggestions should be sent to: Linda A. Olson 610.341.5930 COMMUNITY NEWS..................................................................21 e-mail: [email protected] Alumni news should be sent to: 1.800.600.8057 ATHLETIC NEWS........................................................................25 www.alumni.eastern.edu ALUMNI NEWS MISSION STATEMENT Alumna of the Year ..............................................................................26 Spirit supports the mission of Eastern University to provide a Christian higher Young Alumnus of the Year..................................................................27 education for those who will make a difference in the world through careers and Class Notes ..........................................................................................28 personal -

Engineering Common Curriculum Project Update

For more information, please contact Brian Case, BCcampus Project Manager at [email protected] Engineering Common Curriculum Project Update Update: Fall 2020 Completed Tasks Nov 2019: Five course shells created and shared on BCCAT Moodle site. Project Overview Eleven funding agreements were created to assist help the following institutions move to the common curriculum: In Spring 2019, BCcampus was asked by the Ministry of Advanced Education, Skills and Training to assist with a project concerning B.C. institutions delivering • Capilano University engineering programs who want to move to a common first-year curriculum. • Coast Mountain College The project was initiated by the Engineering Articulation Committee and led by • College of New Caledonia Brian Dick of Vancouver Island University. The work conducted to determine the feasibility of a common first-year curriculum was initially funded through a grant • College of the Rockies from the B.C. Council on Admissions and Transfer. • Langara College • North Island College Project Objectives • Northern Lights College • Selkirk College • Improve access to and opportunity for success in engineering education for • Thompson Rivers University B.C.’s diverse post-secondary learners • Vancouver Community College • Create opportunities for regional community engagement and partnerships • Vancouver Island University within the engineering sector, encouraging graduates to return to employment These institutions are at various stages of in smaller, non-urban communities implementation, with the expectation that • Enhance the student learning environment and improve retention and all will be aligned by the 2021/22 academic achievement in engineering across the province through maximizing use of year (impact of COVID-19 not yet deter- student supports, class size, and regional diversity mined). -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Letter from Selkirk College Board Chair and President ................................................................................... 3 Institutional Overview .........................................................................................................................................4 Mission, Vision and Values ............................................................................................................................. 5 Strategic Directions ......................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Teaching and Learning: Our Fundamental Activity ..................................................................... 6 2. The Student Experience: Access to Success .................................................................................... 7 3. Employees: Key to Our Success ........................................................................................................ 7 4. Leadership: A Commitment to Our Communities ......................................................................... 7 5. Internationalization: Bringing Selkirk to the World and the World to Selkirk .......................... 7 6. Sustainability: Toward Selkirk College as a Green College ........................................................... 7 The Year’s Highlights ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Planning Context -

Langara College

THE 10TH ANNUAL JANUARY 19th–21st, 2017 2017 VGBA LANGARA CHALLENGE OPENING REMARKS The Vancouver Girls Basketball Association welcomes you to our 10th Annual VGBA Langara Challenge. On behalf of our Board of Directors, we send our heartfelt gratitude to our scholarship and tournament organizing committee, along with our sponsors, for allowing us to create this one-of-a-kind elite tournament for our female basketball players in Vancouver. For the sixth year, we are thrilled to expand this tournament to include a Junior Girls Division. This event would not have been possible without the generosity of Langara College and our partnership with both the Vancouver Secondary Schools’ Athletic Association and the Lower Mainland Independent Secondary Schools’ Athletic Association. It is our dream to create a sustainable basketball program for high school girls in Vancouver and continue to provide opportunties where these female athletes can develop their skills, sportsmanship, and a love for the game! Our Objectives 1. To promote, provide, and coordinate girls basketball opportunities for Vancouver student-athletes at all levels of development; participation to elite 2. To build and sustain partnership with other organizations wishing to support the mission statement and objectives of the Association 3. To create a sustainable basketball program for Vancouver girls 4. To provide opportunities for girls to develop basketball skills, sportsmanship, and a love of the game 5. To provide supervised and accessible basketball programs 6. To provide quality coaching and training 7. To develop a core group of volunteer coaches and advisors as board members 8. To establish and maintain a bursary program for girls needing financial assistance to participate in training or playing in club/provincial/national programs 9. -

2021 Catalog 2 3

2020- 2021 1 Hillsdale College 2020 - 2021 Catalog 2 3 Welcome to Hillsdale College independent, four-year college in south-central Michigan, Hillsdale College offers the An rigorous and lively academic experience one expects of a tier-one liberal arts college, and it stands out for its commitment to the enduring principles of the Western tradition. Its core curriculum embodies this commitment through required courses in disciplines such as history, literature, science and politics in order to develop in students the “philosophical habit of mind” essential to sound education. Likewise, majors at Hillsdale are a rigorous and searching extension of these commitments. Ranging from classics or music to chemistry or business, academic fields of concentration build upon the core curriculum, deepening and specifying students’ appreciation for and understanding of the liberal arts. Hillsdale College is dedicated to intellectual inquiry and to learning, and it recognizes essential human dignity. Ordered liberty, personal responsibility, limited government, free enterprise and man’s moral, intellectual and spiritual nature illuminate this dignity and identify the service of the College to its students, the nation, and the Western intellectual and religious tradition. Far-ranging by design and incisive by method, study at Hillsdale College is intellectually demanding. Students work closely with faculty who guide them in their studies, helping students to prepare for a lifetime of accomplishment, leadership, and learning. For more information about Hillsdale College or to arrange a visit, call the Admissions Office at (517) 607-2327, or e-mail [email protected]. • College, founded in 1844, is an independent, coeducational, resi- Hillsdale dential, nonsectarian college for about 1,460 students.