The Philippines an Overview of the Colonial Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military History Anniversaries 01 Thru 14 Feb

Military History Anniversaries 01 thru 14 Feb Events in History over the next 14 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Feb 01 1781 – American Revolutionary War: Davidson College Namesake Killed at Cowan’s Ford » American Brigadier General William Lee Davidson dies in combat attempting to prevent General Charles Cornwallis’ army from crossing the Catawba River in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. Davidson’s North Carolina militia, numbering between 600 and 800 men, set up camp on the far side of the river, hoping to thwart or at least slow Cornwallis’ crossing. The Patriots stayed back from the banks of the river in order to prevent Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tartleton’s forces from fording the river at a different point and surprising the Patriots with a rear attack. At 1 a.m., Cornwallis began to move his troops toward the ford; by daybreak, they were crossing in a double-pronged formation–one prong for horses, the other for wagons. The noise of the rough crossing, during which the horses were forced to plunge in over their heads in the storm-swollen stream, woke the sleeping Patriot guard. The Patriots fired upon the Britons as they crossed and received heavy fire in return. Almost immediately upon his arrival at the river bank, General Davidson took a rifle ball to the heart and fell from his horse; his soaked corpse was found late that evening. Although Cornwallis’ troops took heavy casualties, the combat did little to slow their progress north toward Virginia. -

Colonial Contractions: the Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946

Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Vicente L. Rafael Subject: Southeast Asia, Philippines, World/Global/Transnational Online Publication Date: Jun 2018 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.268 Summary and Keywords The origins of the Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histories of three empires that swept onto its shores: the Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese. This history makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation- states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power rela tionships. Such shifts have included not just regime change but also social revolution. The modernity of the modern Philippines is precisely the effect of the contradictory dynamic of imperialism. The Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese colonial regimes, as well as their postcolonial heir, the Republic, have sought to establish power over social life, yet found themselves undermined and overcome by the new kinds of lives they had spawned. It is precisely this dialectical movement of empires that we find starkly illumi nated in the history of the Philippines. Keywords: Philippines, colonialism, empire, Spain, United States, Japan The origins of the modern Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histo ries of three empires: Spain, the United States, and Japan. This background makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation-states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power relationships. -

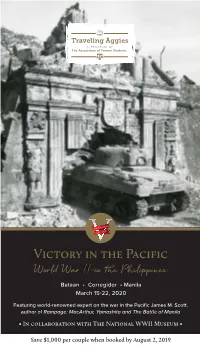

2020 Philippines A&M V2.Indd

y th Year of Victor Victory in the Pacific M A Y 19 4 World War II in the Philippines 5 Bataan • Corregidor • Manila March 15-22, 2020 Featuring world-renowned expert on the war in the Pacific James M. Scott, author of Rampage: MacArthur, Yamashita and The Battle of Manila • In collaboration with The National WWII Museum • Save $1,000 per couple when booked by August 2, 2019 1946 Corregidor Muster. Photo by James T. Danklefs ‘43 Howdy, Ags! On December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the US Pacific Fleet The Traveling Aggies are pleased to partner with The National WWII Museum on at Pearl Harbor. Just a few hours later, the Philippines faced the same fury Victory in the Pacific: World War II in the Philippines. This fascinating journey will as the Japanese Army Air Force began bombing Clark Field, located north of begin in the lush province of Bataan, where tour participants will walk the first Manila. Five months later, the Japanese forced the Americans in the Philippines kilometer of the Death March and visit the remains of the prisoner of war camp at to surrender, but not before General MacArthur could slip away to Australia, Cabanatuan. On the island of Corregidor, 27 miles out in Manila Bay, guests will famously vowing, “I shall return.” see the blasted, skeletal remains of the mile-long barracks, theater, hospital, and officers’ quarters, as well as the monument built and dedicated by The Association After the fall of the Philippines, 70,000 captured American and Filipino soldiers near Malinta Tunnel in 2015, flying the Texas A&M flag and representing the were sent on the infamous “Bataan Death March,” a 65-mile forced march into sacrifice, bravery and Aggie Spirit of the men who Mustered there. -

Happy Independence Day to the Philippines!

Happy Independence Day to the Philippines! Saturday, June 12, 2021, is Philippines Independence Day, or as locals call it, “Araw ng Kasarinlan” (“Day of Freedom”). This annual national holiday honors Philippine independence from Spain in 1898. On June 12, 1898, General Emilio Aguinaldo raised the Philippines flag for the first time and declared this date as Philippines Independence Day. Marcela Agoncillo, Lorenza Agoncillo, and Delfina Herbosa designed the flag of the Philippines, which is famous for its golden sun with eight rays. The rays symbolize the first eight Philippine provinces that fought against Spanish colonial rule. After General Aguinaldo raised the flag, the San Francisco de Malabon marching band played the Philippines national anthem, “Lupang Hinirang,” for the first time. Spain, which had ruled the Philippines since 1565, didn’t recognize General Aguinaldo’s declaration of independence. But at the end of the Spanish-American War in May 1898, Spain surrendered and gave the U.S. control of the Philippines. In 1946, the American government wanted the Philippines to become a U.S. state like Hawaii, but the Philippines became an independent country. The U.S. granted sovereignty to the Philippines on July 4, 1968, through the Treaty of Manila. Filipinos originally celebrated Independence Day on July 4, the same date as Independence Day in the U.S. In 1962, President Diosdado Macapagal changed the date to June 12 to commemorate the end of Spanish rule in the country. This year marks 123 years of the Philippines’ independence from Spanish rule. In 2020, many Filipinos celebrated Independence Day online because of social distancing restrictions. -

World War Ii in the Philippines

WORLD WAR II IN THE PHILIPPINES The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 Copyright 2016 by C. Gaerlan, Bataan Legacy Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. World War II in the Philippines The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 By Bataan Legacy Historical Society Several hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Philippines, a colony of the United States from 1898 to 1946, was attacked by the Empire of Japan. During the next four years, thou- sands of Filipino and American soldiers died. The entire Philippine nation was ravaged and its capital Ma- nila, once called the Pearl of the Orient, became the second most devastated city during World War II after Warsaw, Poland. Approximately one million civilians perished. Despite so much sacrifice and devastation, on February 20, 1946, just five months after the war ended, the First Supplemental Surplus Appropriation Rescission Act was passed by U.S. Congress which deemed the service of the Filipino soldiers as inactive, making them ineligible for benefits under the G.I. Bill of Rights. To this day, these rights have not been fully -restored and a majority have died without seeing justice. But on July 14, 2016, this mostly forgotten part of U.S. history was brought back to life when the California State Board of Education approved the inclusion of World War II in the Philippines in the revised history curriculum framework for the state. This seminal part of WWII history is now included in the Grade 11 U.S. history (Chapter 16) curriculum framework. The approval is the culmination of many years of hard work from the Filipino community with the support of different organizations across the country. -

Nytårsrejsen Til Filippinerne – 2014

Nytårsrejsen til Filippinerne – 2014. Martins Dagbog Dorte og Michael kørte os til Kastrup, og det lykkedes os at få en opgradering til business class - et gammelt tilgodebevis fra lidt lægearbejde på et Singapore Airlines fly. Vi fik hilst på vore 16 glade gamle rejsevenner ved gaten. Karin fik lov at sidde på business class, mens jeg sad på det sidste sæde i økonomiklassen. Vi fik julemad i flyet - flæskesteg med rødkål efterfulgt af ris á la mande. Serveringen var ganske god, og underholdningen var også fin - jeg så filmen "The Hundred Foot Journey", som handlede om en indisk familie, der åbner en restaurant lige overfor en Michelin-restaurant i en mindre fransk by - meget stemningsfuld og sympatisk. Den var instrueret af Lasse Hallström. Det tog 12 timer at flyve til Singapore, og flyet var helt fuldt. Flytiden mellem Singapore og Manila var 3 timer. Vi havde kun 30 kg bagage med tilsammen (12 kg håndbagage og 18 kg i en indchecket kuffert). Jeg sad ved siden af en australsk student, der skulle hjem til Perth efter et halvt år i Bergen. Hans fly fra Lufthansa var blevet aflyst, så han havde måttet vente 16 timer i Københavns lufthavn uden kompensation. Et fly fra Air Asia på vej mod Singapore forulykkede med 162 personer pga. dårligt vejr. Miriams kuffert var ikke med til Manilla, så der måtte skrives anmeldelse - hun fik 2200 pesos til akutte fornødenheder. Vi vekslede penge som en samlet gruppe for at spare tid og gebyr - en $ var ca. 45 pesos. Vi kom i 3 minibusser ind til Manila Hotel, hvor det tog 1,5 time at checke os ind på 8 værelser. -

Hall's Manila Bibliography

05 July 2015 THE RODERICK HALL COLLECTION OF BOOKS ON MANILA AND THE PHILIPPINES DURING WORLD WAR II IN MEMORY OF ANGELINA RICO de McMICKING, CONSUELO McMICKING HALL, LT. ALFRED L. McMICKING AND HELEN McMICKING, EXECUTED IN MANILA, JANUARY 1945 The focus of this collection is personal experiences, both civilian and military, within the Philippines during the Japanese occupation. ABAÑO, O.P., Rev. Fr. Isidro : Executive Editor Title: FEBRUARY 3, 1945: UST IN RETROSPECT A booklet commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Liberation of the University of Santo Tomas. ABAYA, Hernando J : Author Title: BETRAYAL IN THE PHILIPPINES Published by: A.A. Wyn, Inc. New York 1946 Mr. Abaya lived through the Japanese occupation and participated in many of the underground struggles he describes. A former confidential secretary in the office of the late President Quezon, he worked as a reporter and editor for numerous magazines and newspapers in the Philippines. Here he carefully documents collaborationist charges against President Roxas and others who joined the Japanese puppet government. ABELLANA, Jovito : Author Title: MY MOMENTS OF WAR TO REMEMBER BY Published by: University of San Carlos Press, Cebu, 2011 ISBN #: 978-971-539-019-4 Personal memoir of the Governor of Cebu during WWII, written during and just after the war but not published until 2011; a candid story about the treatment of prisoners in Cebu by the Kempei Tai. Many were arrested as a result of collaborators who are named but escaped punishment in the post war amnesty. ABRAHAM, Abie : Author Title: GHOST OF BATAAN SPEAKS Published by: Beaver Pond Publishing, PA 16125, 1971 This is a first-hand account of the disastrous events that took place from December 7, 1941 until the author returned to the US in 1947. -

Flipping the Script: Gabriela Silang's Legacy Through Stagecraft

Dominican Scholar Humanities & Cultural Studies | Senior Liberal Arts and Education | Theses Undergraduate Student Scholarship 5-2020 Flipping the Script: Gabriela Silang’s Legacy through Stagecraft Leeann Francisco Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2020.HCS.ST.02 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Francisco, Leeann, "Flipping the Script: Gabriela Silang’s Legacy through Stagecraft" (2020). Humanities & Cultural Studies | Senior Theses. 2. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2020.HCS.ST.02 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberal Arts and Education | Undergraduate Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Humanities & Cultural Studies | Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Flipping the Script: Gabriela Silang’s Legacy through Stagecraft By Leeann Francisco A culminating thesis submitted to the faculty of Dominican University of California in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Humanities Dominican University of California San Rafael, CA May 2020 ii Copyright © Francisco 2020. All rights reserved iii ABSTRACT Flipping the Script: Gabriela Silang’s Legacy through Stagecraft is a chronicle of the scriptwriting and staging process for Bannuar, a historical adaptation about the life of Gabriela Silang (1731-1763) produced by Dominican University of California’s (DUC) Filipino student club (Kapamilya) for their annual Pilipino Cultural Night (PCN). The 9th annual show was scheduled for April 5, 2020. Due to the limitations of stagecraft, implications of COVID-19, and shelter-in-place orders, the scriptwriters made executive decisions on what to omit or adapt to create a well-rounded script. -

Spanish Colonialism in the Philippines

Spanish colonialism in The Philippines Portugese explorer Ferdinand Magellan successfully led the European expedition to Philippines in the service of the King of Spain. On 31 March 1521 at Limasawa Island, Southern Leyte, as stated in Pigafetta's Primo Viaggio Intorno El Mondo (First Voyage Around the World), Magellan solemnly planted a cross on the summit of a hill overlooking the sea and claimed for the king of Spain possession of the islands he had seen, naming them Archipelago of Saint Lazarus . The invasion of Philippines by foreign powers however didn’t begin in earnest until 1564. After Magellan's voyage, subsequent expeditions were dispatched to the islands. Four expeditions were sent: Loaisa (1525), Cabot (1526), Saavedra (1527), Villalobos (1542), and Legazpi (1564) by Spain. The Legazpi expedition was the most successful as it resulted in the discovery of the tornaviaje or return trip to Mexico across the Pacific by Andrés de Urdaneta . This discovery started the Manila galleon trade 1, which lasted two and a half centuries. In 1570, Martín de Goiti having been dispatched by Legazpi to Luzon 2, conquered the Kingdom of Maynila (now Manila ). Legazpi then made Maynila the capital of the Philippines and simplified its spelling to Manila . His expedition also renamed Luzon Nueva Castilla . Legazpi became the country's first governor-general. The archipelago was Spain's outpost in the orient and Manila became the capital of the entire Spanish East Indies . The colony was administered through the Viceroyalty of New Spain (now Mexico) until 1821 when Mexico achieved independence from Spain. After 1821, the colony was governed directly from Spain. -

Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914

Allegiance and Identity: Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914 by M. Carmella Cadusale Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2016 Allegiance and Identity: Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914 M. Carmella Cadusale I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: M. Carmella Cadusale, Student Date Approvals: Dr. L. Diane Barnes, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. David Simonelli, Committee Member Date Dr. Helene Sinnreich, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT Filipino culture was founded through the amalgamation of many ethnic and cultural influences, such as centuries of Spanish colonization and the immigration of surrounding Asiatic groups as well as the long nineteenth century’s Race of Nations. However, the events of 1898 to 1914 brought a sense of national unity throughout the seven thousand islands that made the Philippine archipelago. The Philippine-American War followed by United States occupation, with the massive domestic support on the ideals of Manifest Destiny, introduced the notion of distinct racial ethnicities and cemented the birth of one national Philippine identity. The exploration on the Philippine American War and United States occupation resulted in distinguishing the three different analyses of identity each influenced by events from 1898 to 1914: 1) The identity of Filipinos through the eyes of U.S., an orientalist study of the “us” versus “them” heavily influenced by U.S. -

The Thirteenth Minnesota and the Mock Battle of Manila by Kyle Ward on the Evening of February 15, 1898, There Was an Explosion Within the U.S.S

winter16allies_Layout 1 1/20/2016 4:20 PM Page 1 Winter, 2016 Vol. XXIV, No. 1 The Thirteenth Minnesota and the mock battle of Manila By Kyle Ward On the evening of February 15, 1898, there was an explosion within the U.S.S. Maine, which was stationed in Havana Harbor outside the Cuban capital city. Had it happened anywhere else in the world, this event proba- bly would not have had such huge implications, but be- cause it happened when and where it did, it had a major impact on the course of American history. And although it happened 2,000 miles from Minnesota, it had a huge impact on Minnesotans as well. The sinking of the USS Maine, which killed 266 crew members, was like the last piece of a vast, complex puzzle that, once pressed into place, completed the pic- ture and caused the United States and the nation of Spain to declare war against one another. Their diplomatic hos- tilities had been going on for a number of years, primarily due to Cuban insurgents trying to break away from their long-time colonial Spanish masters. Spain, for its part, The battle flags of the Thirteenth Minnesota, flown at camp in San Francisco, California. (All photos for this story are from the was trying to hold on to the last remnants of its once collection of the Minnesota Historical Society.) great empire in the Western Hemisphere. Many Americans saw a free Cuba as a potential region for investment and growth, while others sided with April 23, 1898, President William McKinley, a Civil War the Cubans because it reminded them of their own na- veteran, asked for 125,000 volunteers from the states to tion’s story of a small rebel army trying to gain independ- come forward and serve their nation. -

5 Filipino Heroines Who Changed Philippine History

REMARKABLE FILIPINO WOMEN HEROES LINK : https://cnnphilippines.com/life/culture/2017/06/07/5-filipino-heroines.html 5 Filipino heroines who changed Philippine history Manila (CNN Philippines Life) — When asked to give at least three names of Philippine heroes, who are the first people that come to mind? Of course Jose Rizal is a given as the national hero. And then there’s Andres Bonifacio, Emilio Aguinaldo, and Emilio Jacinto. Perhaps even throw in Antonio Luna thanks to successful historical film “Heneral Luna” (2015). The Philippines does not have an official list of national heroes. While there has been an attempt to come up with one, legislators deferred finalizing a list to avoid a deluge of proclamations and debates “involving historical controversies about heroes.” Still, textbooks and flashcards don’t hesitate to ingrain their names in our minds. It’s interesting how these historical figures all breed the same familiarity as superheroes, with students already knowing their names and achievements by heart by the time they reach high school. Thinking about the personalities, you can’t help but notice a pattern: they’re mostly men who fit into the typical hero mold of machismo and valor. While history books often devote entire chapters to the adventures and achievements of male heroes, our female heroines are often bunched into one section, treated as footnotes or afterthoughts despite also fighting for the nation’s freedom. In time for Independence Day, CNN Philippines Life lists five brave Filipino heroines whose actions deserve to be remembered. These women are more than just tokens for female representation.