Malaysia Brunei 1997-98

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitutional & Parliamentary Information

UNION INTERPARLEMENTAIRE INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION CCoonnssttiittuuttiioonnaall && PPaarrlliiaammeennttaarryy IInnffoorrmmaattiioonn Half-yearly Review of the Association of Secretaries General of Parliaments Preparations in Parliament for Climate Change Conference 22 in Marrakech (Abdelouahed KHOUJA, Morocco) National Assembly organizations for legislative support and strengthening the expertise of their staff members (WOO Yoon-keun, Republic of Korea) The role of Parliamentary Committee on Government Assurances in making the executive accountable (Shumsher SHERIFF, India) The role of the House Steering Committee in managing the Order of Business in sittings of the Indonesian House of Representatives (Dr Winantuningtyastiti SWASANANY, Indonesia) Constitutional reform and Parliament in Algeria (Bachir SLIMANI, Algeria) The 2016 impeachment of the Brazilian President (Luiz Fernando BANDEIRA DE MELLO, Brazil) Supporting an inclusive Parliament (Eric JANSE, Canada) The role of Parliament in international negotiations (General debate) The Lok Sabha secretariat and its journey towards a paperless office (Anoop MISHRA, India) The experience of the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies on Open Parliament (Antonio CARVALHO E SILVA NETO) Web TV – improving the score on Parliamentary transparency (José Manuel ARAÚJO, Portugal) Deepening democracy through public participation: an overview of the South African Parliament’s public participation model (Gengezi MGIDLANA, South Africa) The failed coup attempt in Turkey on 15 July 2016 (Mehmet Ali KUMBUZOGLU) -

Tourism and the Refashioning of the Headhunting Narrative in Sabah

“I Lost My Head in Borneo” “I Lost My Head in Borneo”: their understanding of the joke and thus Tourism and the guard their indigenousness and their status as human beings. I also argue that their use Refashioning of the of their headhunting heritage is a means of Headhunting Narrative in responding to the threats to their identities Sabah, Malaysia posed by the Malaysian state, which, in the process of globalization and nation building, has interpolated them into a Malaysian iden- Flory Ann Mansor Gingging tity, an identity that they seem to resist in Indiana University, Bloomington favor of their regional ones. This paper looks USA at what tourism’s refashioning of the headhunting narrative might suggest about Abstract how Sabah’s indigenous groups respond to their former colonization by the West and Although headhunting is generally believed how they imagine and negotiate their identi- to be no longer practiced in Sabah, Malay- ties within the constraints of membership sia, it is a phenomenon of the past that still within the state of Malaysia.1 exists in the collective consciousness of in- digenous groups, living through the telling and retelling of stories, not just by individu- spent a large part of my growing-up als, but also by the tourism industry. The years in Tamparuli, a small town near headhunting image and theme are ubiqui- the west coast of Sabah, a Malaysian I 2 tous in the tourist literature and campaigns. state in northern Borneo. A river divides They are featured on postcards, brochures, the town proper and the compound on and T-shirts (a particular favorite shows an which my family and I lived, so sojourns orangutan head with the caption “I lost my to the other side—to tamu (weekly mar- head in Borneo”). -

20210106111314445 Gohmert V Pence Stay Appl Signed.Pdf

No. __A__________ In the Supreme Court of the United States LOUIE GOHMERT, TYLER BOWYER, NANCY COTTLE, JAKE HOFFMAN, ANTHONY KERN, JAMES R. LAMON, SAM MOORHEAD, ROBERT MONTGOMERY, LORAINE PELLEGRINO, GREG SAFSTEN, KELLI WARD AND MICHAEL WARD, Applicants, v. THE HONORABLE MICHAEL R. PENCE, VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY. Respondent. EMERGENCY APPLICATION TO THE HONORABLE SAMUEL A. ALITO AS CIRCUIT JUSTICE FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT FOR ADMINISTRATIVE STAY AND INTERIM RELIEF PENDING RESOLUTION OF A TIMELY FILED PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI William L. Sessions Sidney Powell* Texas Bar No. 18041500 Texas Bar No. 16209700 SESSIONS & ASSOCIATES, PLLC SIDNEY POWELL, P.C. 14591 North Dallas Parkway, Suite 400 2911 Turtle Creek Blvd., Suite 1100 Dallas, TX 75254 Dallas, TX 72519 Tel: (214) 217-8855 Tel: (214) 628-9514 Fax: (214) 723-5346 Fax: (214) 628-9505 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Lawrence J. Joseph Howard Kleinhendler DC Bar #464777 NY Bar No. 2657120 LAW OFFICE OF LAWRENCE J. JOSEPH HOWARD KLEINHENDLER ESQUIRE 1250 Connecticut Av NW, Ste 700 369 Lexington Ave., 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 New York, New York 10017 Tel: (202) 355-9452 Tel: (917) 793-1188 Fax: (202) 318-2254 Fax: (732) 901-0832 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Counsel for Applicants * Counsel of Record PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING Applicants (plaintiffs-appellants below) are U.S. Rep. Louie Gohmert (TX-1), Tyler Bowyer, Nancy Cottle, Jake Hoffman, Anthony Kern, James R. Lamon, Sam Moorhead, Robert Montgomery, Loraine Pellegrino, Greg Safsten, Kelli Ward, and Michael Ward. Respondent (defendant-appellee below) is the Honorable Michael R. -

1925 Congressional Reoord-Sen Ate 1945

1925 CONGRESSIONAL REOORD-SEN ATE 1945 By Mr. WYANT: A bill (H. R. 11699) granting an increase ance blll (S. 3218) ; to the Committee en the District of of pension to Elizabeth Clark; to the Committee on Invalld Columbia. Pensions. 3471. Also, petition of G. H. Martin and others, protesting Also, a bill (H. R. 11700) gran!ing an increase of pension against the Sunday observance bill· .( S" 3218) ; to the Com· to Mary L. Deemet ; to the Oomm1ttee on Invalid Pensions. mittee on the District of Columbia. By Mr. KNUTSON: Resolution (H. Res. 405) to pay to Walter C. Neilson $1,500 for extra and expert services to the Committee on Pensions by detail from the Bureau of Pensions ; SENATE to the Committee on Accounts. FRIDAY, January 16, 1925 PETITIONS, ETC. (Legislative day of Thursday, Jatntu.a1"1J 15, 1!125) Under clause 1 of Rule XXII, petitions and papers were laid The Senate met in open executive session at 12 o'clock on the Clerk's· desk and referred as follows: meridian, on the expiration of the recess. 3456. By the SPEAKER (by request) : Petition of Federation The PRESIDENT pro tempore. The Ohair lays before the of Citizens' Associations of the District of Columbia, asking for Senate the treaty with Cuba. a more definite proportionate contribution by the Federal Gov l\.lt. CURTIS. M.r. President, I suggest the absence of a ernment and the District of Columbia in appropriations for the quorum. maintenance, upkeep, and development of the Federal territory; The PRESIDENT pro temp01·e. The Clerk will call the to the Committee on the District of Columbia. -

Congressional Record-Senate. 2673

1880. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. 2673 Helfferich & Sons, and of George C. Buchanan and others, of Ken Mr. DAWES. The same joint resolution which passed the House tucky and Ohio, for the passage of the bill (H. R. No. 4812) amending must have passed the Senate. There could not have been two reso the internal-revenue laws-to the Committee on Ways and Means. lutions. That may be a mistake of the RECORD, but it oa.nnot be Also, the petitions of G. Holterhoff, of Schmidlapp & Co., of otherwise than the same resolution. There may have been a mistake .Amann & Co., of Cincinnati, Ohio, for a revision of the revenue laws in copying. relative to the tax on whisky-t o the same committee. Mr. BECK. I do not know the fact; I have not verified it . ~ Also, the petition of the Iron Molders' Union of Lorain, Ohio, for Mr. DAWES. I wish to call the at tention of the Senator from Ken the passage of House bill 4327-to the Committee on the Judiciary. tucky to a little error in the RECORD as reported. I did not inquire Also, the petition of Charles N. Parat and others, for the removal of the Senator, as I am reported there, whether he was opposed to of the duty on foreign newspapers and periodicals-to the Committee the resolution; I inquired of the Senator if he objected to the word on Ways and Means. ' "nation." I am reported as inquiring of the Senator if he was op Also, the petition of James Morrison & Co. -

A History of Southeast Asia

ARTHUR AHISTORYOF COTTERELL SOUTHEAST AHISTORYOF ASIA SOUTHE A HISTORY OF OF HISTORY About the Author A History of Southeast Asia is a sweeping and wide-ranging SOUTHEAST Arthur Cotterell was formerly principal of Kingston narration of the history of Southeast Asia told through historical College, London. He has lived and travelled widely anecdotes and events. in Asia and Southeast Asia, and has devoted ASIA much of his life to writing on the region. In 1980, Superbly supported by over 200 illustrations, photographs and he published !e First Emperor of China, whose maps, this authoritative yet engagingly written volume tells the account of Qin Shi Huangdi’s remarkable reign was history of the region from earliest recorded times until today, translated into seven languages. Among his recent covering present-day Myanmar, !ailand, Cambodia, Laos, AS books are Western Power in Asia: Its Slow Rise and Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, the Philippines, Indonesia Swift Fall 1415–1999, and Asia: A Concise History, and East Timor. T A published in 2011, the "rst ever coverage of the entire continent. “Arthur Cotterell writes in a most entertaining way by putting a human face on the history of Asia. Far too often, “Arthur Cotterell writes in a most entertaining history books are dry and boring and it is refreshing SIA way by putting a human face on the history of Asia.” to come across one which is so full of life. - to be changed” – Peter Church, OAM, author of A Short History of South East Asia, on Arthur Cotterell – Professor Bruce Lockhart -

Uhm Ma 3222 R.Pdf

Ui\i1VEi~.'3!TY OF HA\/VAI'I LIBRARY PLANNING KADAZANDUSUN (SABAH, MALAYSIA): LABELS, IDENTITY, AND LANGUAGE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2005 By Trixie M. Tangit Thesis Committee: AndrewD. W. Wong, Chairperson Kenneth L. Rehg Michael L. Fonnan © 2005, Trixie M. Tangit 111 For the Kadazandusun community in Sabah, Malaysia and for the beloved mother tongue IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to take this opportunity to record my gratitude and heartfelt thanks to all those who have helped. me to accomplish my study goals throughout the M.A. program. Firstly, my thanks and appreciation to the participants who have contributed to this study on the Kadazandusun language: In particular, I thank Dr. Benedict Topin (from the Kadazan Dusun Cultural Association (KDCA», Ms. Evelyn Annol (from the Jabatan Pendidikan Negeri Sabab/ Sabah state education department (JPNS», and Ms. Rita Lasimbang (from the Kadazandusun Language Foundation (KLF». I also take this opportunity to thank Mr. Joe Kinajil, ex-JPNS coordinator (retired) ofthe Kadazandusun language program in schools, for sharing his experiences in the early planning days ofthe Kadazandusun language and for checking language data. I also wish to record my sincere thanks to Ms. Pamela Petrus Purser and Mr. Wendell Gingging for their kind assistance in checking the language data in this thesis. Next, my sincere thanks and appreciation to the academic community at the Department ofLinguistics, University ofHawai'i at Manoa: In particular, mahalo nui loa to my thesis committee for their feedback, support, and advice. -

INDIGENOUS GROUPS of SABAH: an Annotated Bibliography of Linguistic and Anthropological Sources

INDIGENOUS GROUPS OF SABAH: An Annotated Bibliography of Linguistic and Anthropological Sources Part 1: Authors Compiled by Hans J. B. Combrink, Craig Soderberg, Michael E. Boutin, and Alanna Y. Boutin SIL International SIL e-Books 7 ©2008 SIL International Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2008932444 ISBN: 978-155671-218-0 Fair Use Policy Books published in the SIL e-Books series are intended for scholarly research and educational use. You may make copies of these publications for research or instructional purposes (under fair use guidelines) free of charge and without further permission. Republication or commercial use of SILEB or the documents contained therein is expressly prohibited without the written consent of the copyright holder(s). Series Editor Mary Ruth Wise Volume Editor Mae Zook Compositor Mae Zook The 1st edition was published in 1984 as the Sabah Museum Monograph, No. 1. nd The 2 edition was published in 1986 as the Sabah Museum Monograph, No. 1, Part 2. The revised and updated edition was published in 2006 in two volumes by the Malaysia Branch of SIL International in cooperation with the Govt. of the State of Sabah, Malaysia. This 2008 edition is published by SIL International in single column format that preserves the pagination of the 2006 print edition as much as possible. Printed copies of Indigenous groups of Sabah: An annotated bibliography of linguistic and anthropological sources ©2006, ISSN 1511-6964 may be obtained from The Sabah Museum Handicraft Shop Main Building Sabah Museum Complex, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, -

Our Readers Author Thanks Send Us Your Feedback

328 SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to postal submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/privacy. Helen van Lindere, Jeremy Clark, Peter Hogge OUR READERS and my guides Bian Rumai, Esther Abu, Many thanks to the travellers who used Jeffry Simun, Susan Pulut and Syria Lejau the last edition and wrote to us with help- (Gunung Mulu National Park); Apoi Ngimat, ful hints, useful advice and interesting Jaman Riboh, Joanna Joy, Rebita Lupong, anecdotes: Antonio Almeida, Alexandra Bardswell, Tamara Rian John Pasan Lamulun, Stephen and Tine, Bedeaux, Neesha Copley, Augusto Garolla, and Stu Roach (Bario); Mr Lim (Chong Teah), Paul Gurn, Lloyd Jones, Laurel -

Global Parliamentary Report: Global Parliamentary Report: the Changing Naturerepresentation of Parliamentary IPU - UNDP

GLOBAL PARLIAMENTARY Better parliaments, stronger democracies. REPORT The changing nature of parliamentary representation Global Parliamentary Report: The changing nature of parliamentary changing nature representation The Global Parliamentary Report: IPU - UNDP. 2012 IPU - UNDP. Inter-Parliamentary Union ❙ United Nations Development Programme Lead author: Greg Power Assistant to the lead author: Rebecca A. Shoot Translation: Sega Ndoye (French), Peritos Traductores, S.C. (Spanish), Houria Qissi (Arabic) Cover design and layout: Kimberly Koserowski, First Kiss Creative LLC Printing: Phoenix Design Aid A/S Sales: United Nations Publications Photo credits: Cover Illustration: James Smith, pg. 9: UN Photo/Albert Gonzalez Farran, pg. 24: UK Parliament copyright, pg. 42: UNDP/Afghanistan, pg. 58: Fabián Rivadeneyra, pg. 72: Assemblée nationale 2012 April 2012 Copyright © UNDP and IPU All rights reserved Printed in Denmark Sales No.: E.11.III.B.19 ISBN: 978-92-1-126317-6 (UNDP) ISBN: 978-92-9142-532-7 (IPU) eISBN: 978-92-1-054990-5 Inter-Parliamentary Union United Nations Development Programme 5 chemin du Pommier Democratic Governance Group CH-1218 Le Grand-Saconnex Bureau for Development Policy Geneva, Switzerland 304 East 45th Street, 10th Floor Telephone: +41 22 919 41 50 New York, NY, 10017, USA Fax: +41 22 919 41 60 Telephone: +1 (212) 906 5000 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +1 (212) 906 5857 www.ipu.org www.undp.org This publication results from the partnership between UNDP and IPU. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations, UNDP or IPU. Better parliaments, stronger democracies. GLOBAL PARLIAMENTARY REPORT The changing nature of parliamentary representation Inter-Parliamentary Union ❙ United Nations Development Programme April 2012 ADVISORY BOARD ■ Mr. -

Treaty of New Echota

INDIAN- AFFAIRS. LAWS AN-D TREATIES. V,:-1. II. (TREATIES.) COMPILED AND EDITED .,BY CHARLES J. KAPPLER, LL. M., CLERK TO THE SENATE COMMITTEE ON INDIAN AFFAIRS. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1904. TREATY ·WITH THE CHEROKEE, 1835. 439 In presence of~ R. B. Mason, major of dragoons, Augustine A. Chouteau, G. Birch, major, U. S. Army, .John Hambly, United States interpreter Francis Lee, captain, Seventh Infantry, to the Creeks, Samuel G. I. DeCamp, surgeon, George Herron, W. Seawdl, lieutenant and aid de camp; Leonard C. McPhail, assistant surgeon, secretary to the commissioners, U.S. Army, Thomas B. Ballard, Robert M. French. ! TREATY WITH THE CHEROKEE, 1835. Articles of a treaty, concluded at New Echota in the State of Georqia _ Dec. 29• 1~-~ on the 2.9th day of Deer. 1835 by General William Carroll and John 7 stat., 478· a z z • • z f z TT • d S d Proclamation May F.. DCnermer,wrn commissioners on tne part (!, tne unite tates an 23, 1836. ' the Chiefs I£ead Men and People of the Oherolcee tribe of Indians. WHEREAS the Cherokees are anxious to make some arrangements Preamble with the Government of the United States whereby the difficulties they have experienced by a residence within the settled parts of the United States under the jurisdiction and laws of the State Governments may be terminated and adjusted; and with a view to reuniting their people in one body and securing a permanent home for themselves and their posterity in the country selected by their forefathers without the ter ritorial limifa of the State sovereignties, and where they can establish and enjoy a government of their choice and perpetuate such a state of society as may be most consonant with their views, habits and condi tion; and as may tend to their individual comfort and their advance ment in civilization. -

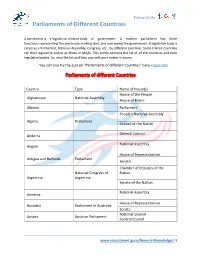

Parliaments of Different Countries

Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries A parliament is a legislative, elected body of government. A modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government. A legislative body is called as a Parliament, National Assembly, Congress, etc., by different countries. Some Islamic countries call their legislative bodies as Shora or Majlis. This article contains the list of all the countries and their legislative bodies. So, read the list and help yourself score better in exams. You can also try the quiz on “Parliaments of different Countries” here – Quiz Link Parliaments of different Countries Country Type Name of house(s) House of the People Afghanistan National Assembly House of Elders Albania Parliament People's National Assembly Algeria Parliament Council of the Nation General Council Andorra National Assembly Angola House of Representatives Antigua and Barbuda Parliament Senate Chamber of Deputies of the National Congress of Nation Argentina Argentina Senate of the Nation National Assembly Armenia House of Representatives Australia Parliament of Australia Senate National Council Austria Austrian Parliament Federal Council www.recruitment.guru/General-Knowledge/|1 Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries Azerbaijan National Assembly House of Assembly Bahamas, The Parliament Senate Council of Representatives Bahrain National Assembly Consultative Council National Parliament Bangladesh House of Assembly Barbados Parliament Senate House of Representatives National Assembly