20210106111314445 Gohmert V Pence Stay Appl Signed.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Little Nazis KE V I N D

20170828 subscribers_cover61404-postal.qxd 8/22/2017 3:17 PM Page 1 September 11, 2017 $5.99 TheThe Little Nazis KE V I N D . W I L L I A M S O N O N T H E C HI L D I S H A L T- R I G H T $5.99 37 PLUS KYLE SMITH: The Great Confederate Panic MICHAEL LIND: The Case for Cultural Nationalism 0 73361 08155 1 www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 1/3/2017 5:38 PM Page 1 !!!!!!!! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! "e Reagan Ranch Center ! 217 State Street National Headquarters ! 11480 Commerce Park Drive, Santa Barbara, California 93101 ! 888-USA-1776 Sixth Floor ! Reston, Virginia 20191 ! 800-USA-1776 TOC-FINAL_QXP-1127940144.qxp 8/23/2017 2:41 PM Page 1 Contents SEPTEMBER 11, 2017 | VOLUME LXIX, NO. 17 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 22 Lucy Caldwell on Jeff Flake The ‘N’ Word p. 15 Everybody is ten feet tall on the BOOKS, ARTS Internet, and that is why the & MANNERS Internet is where the alt-right really lives, one big online 35 THE DEATH OF FREUD E. Fuller Torrey reviews Freud: group-therapy session The Making of an Illusion, masquerading as a political by Frederick Crews. movement. Kevin D. Williamson 37 ILLUMINATIONS Michael Brendan Dougherty reviews Why Buddhism Is True: The COVER: ROMAN GENN Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment, ARTICLES by Robert Wright. DIVIDED THEY STAND (OR FALL) by Ramesh Ponnuru 38 UNJUST PROSECUTION 12 David Bahnsen reviews The Anti-Trump Republicans are not facing their challenges. -

Public Comments

Timestamp Meeting Date Agenda Item First and Last Name Zip Code Representing Comments It is inappropriate to use an obviously biased company for Arizona’s redistricting mapping process. Bernie Sanders and Barack Obama should have zero say in what our maps look like, and these companies are funded by them at the national level. We want you to hire the National Demographics Corporation – Douglas Johnson in order to assure Arizonans of fair representation and elections. The “Independent” Review Council should make amends for ten years of incompetence and corruption. The commissioners met as many as five times at the home of the AZ 4/27/2021 9:12:25 April 27, 2021 Redistricting Marta 85331 Democratic Party’s Executive Director! It is inappropriate to use an obviously biased company for Arizona’s redistricting mapping process. Bernie Sanders and Barack Obama should have zero say in what our maps look like, and these companies are funded by them at the national level. We want you to hire the National Demographics Corporation – Douglas Johnson in order to assure Arizonans of fair representation and elections. The “Independent” Review Council should make amends for ten years of incompetence Redistricting and corruption. The commissioners met as many as five times at the home of the AZ 4/27/2021 9:12:47 April 27, 2021 Company Michael MacBan 85331 Democratic Party’s Executive Director! I would l ke to request that the company to be hired is the National Demographics Corporation – Douglas Johnson, in order to assure Arizonans fair representation and redistricting elections. mapping It would be inappropriate to use a biased company for the redistricting mapping process. -

Constitutional & Parliamentary Information

UNION INTERPARLEMENTAIRE INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION CCoonnssttiittuuttiioonnaall && PPaarrlliiaammeennttaarryy IInnffoorrmmaattiioonn Half-yearly Review of the Association of Secretaries General of Parliaments Preparations in Parliament for Climate Change Conference 22 in Marrakech (Abdelouahed KHOUJA, Morocco) National Assembly organizations for legislative support and strengthening the expertise of their staff members (WOO Yoon-keun, Republic of Korea) The role of Parliamentary Committee on Government Assurances in making the executive accountable (Shumsher SHERIFF, India) The role of the House Steering Committee in managing the Order of Business in sittings of the Indonesian House of Representatives (Dr Winantuningtyastiti SWASANANY, Indonesia) Constitutional reform and Parliament in Algeria (Bachir SLIMANI, Algeria) The 2016 impeachment of the Brazilian President (Luiz Fernando BANDEIRA DE MELLO, Brazil) Supporting an inclusive Parliament (Eric JANSE, Canada) The role of Parliament in international negotiations (General debate) The Lok Sabha secretariat and its journey towards a paperless office (Anoop MISHRA, India) The experience of the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies on Open Parliament (Antonio CARVALHO E SILVA NETO) Web TV – improving the score on Parliamentary transparency (José Manuel ARAÚJO, Portugal) Deepening democracy through public participation: an overview of the South African Parliament’s public participation model (Gengezi MGIDLANA, South Africa) The failed coup attempt in Turkey on 15 July 2016 (Mehmet Ali KUMBUZOGLU) -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 167 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 6, 2021 No. 4 House of Representatives The House met at noon and was and our debates, that You would be re- OFFICE OF THE CLERK, called to order by the Speaker pro tem- vealed and exalted among the people. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, pore (Mr. SWALWELL). We pray these things in the strength Washington, DC, January 5, 2021. of Your holy name. Hon. NANCY PELOSI, f Speaker, House of Representatives, Amen. DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER Washington, DC. PRO TEMPORE f DEAR MADAM SPEAKER: Pursuant to the permission granted in Clause 2(h) of Rule II The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- THE JOURNAL of the Rules of the U.S. House of Representa- fore the House the following commu- tives, I have the honor to transmit a sealed nication from the Speaker: The SPEAKER pro tempore. Pursu- envelope received from the White House on ant to section 5(a)(1)(A) of House Reso- January 5, 2021 at 5:05 p.m., said to contain WASHINGTON, DC, January 6, 2021. lution 8, the Journal of the last day’s a message from the President regarding ad- I hereby appoint the Honorable ERIC proceedings is approved. ditional steps addressing the threat posed by SWALWELL to act as Speaker pro tempore on applications and other software developed or f this day. controlled by Chinese companies. With best wishes, I am, NANCY PELOSI, PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE Speaker of the House of Representatives. -

Post-Election Day Scenarios October 27, 2020

HealthyElections.org Post-Election Day Scenarios October 27, 2020 Abstract: Confronted with likely delays in counting an unprecedented number of mail-in ballots, close vote counts in key battleground states, the prospect of allegations of election fraud, and an intensely polarized political climate, the United States faces the possibility of highly contested election results on and after November 3. This paper explores some unlikely but conceivable scenarios that could emerge, such as a state legislature's appointment of a slate of electors before the state’s popular vote is fully counted, a Congress faced with two conicting slates of electors from the same state, and the death of a presidential candidate. These G oogle Slides correspond to the content of this memo and might be useful for a presentation covering the material. Authors : Maia Brockbank, Joven Hundal, Zahavah Levine, Anastasiia Malenko, and Alissa Vuillier Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Introduction 2 November 4 - December 13: Post-Election Day Scenarios 2 Scenario 1: State Legislature Appoints Electors Before Popular Vote is Certied 2 December 14 - January 6: Reporting Votes to Congress 4 Scenario 2: State Misses Deadline to Send Its Slate to Electoral College 4 Scenario 3: Faithless Electors Defect and Change Election Outcome 5 January 6 -19: Congressional Counting of Electoral Votes 5 Scenario 4: Congress Faces Two Conicting Electoral Slates from a State 6 Scenario 5: No Candidate Receives a Majority of Electoral Votes 9 January 20: Inauguration Day 10 Scenario 6: No Clear Winner on Inauguration Day 10 Scenario 7: Judicial Intervention Determines Election Outcome 10 A Presidential Candidate Dies 11 Scenario 8: A Presidential Candidate Dies Before or After Election Day 11 Introduction The 2020 presidential election has already emerged as one of the most hotly contested in American history. -

Philippines's Constitution of 1987

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 constituteproject.org Philippines's Constitution of 1987 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 Table of contents Preamble . 3 ARTICLE I: NATIONAL TERRITORY . 3 ARTICLE II: DECLARATION OF PRINCIPLES AND STATE POLICIES PRINCIPLES . 3 ARTICLE III: BILL OF RIGHTS . 6 ARTICLE IV: CITIZENSHIP . 9 ARTICLE V: SUFFRAGE . 10 ARTICLE VI: LEGISLATIVE DEPARTMENT . 10 ARTICLE VII: EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT . 17 ARTICLE VIII: JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT . 22 ARTICLE IX: CONSTITUTIONAL COMMISSIONS . 26 A. COMMON PROVISIONS . 26 B. THE CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION . 28 C. THE COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS . 29 D. THE COMMISSION ON AUDIT . 32 ARTICLE X: LOCAL GOVERNMENT . 33 ARTICLE XI: ACCOUNTABILITY OF PUBLIC OFFICERS . 37 ARTICLE XII: NATIONAL ECONOMY AND PATRIMONY . 41 ARTICLE XIII: SOCIAL JUSTICE AND HUMAN RIGHTS . 45 ARTICLE XIV: EDUCATION, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, ARTS, CULTURE, AND SPORTS . 49 ARTICLE XV: THE FAMILY . 53 ARTICLE XVI: GENERAL PROVISIONS . 54 ARTICLE XVII: AMENDMENTS OR REVISIONS . 56 ARTICLE XVIII: TRANSITORY PROVISIONS . 57 Philippines 1987 Page 2 constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 • Source of constitutional authority • General guarantee of equality Preamble • God or other deities • Motives for writing constitution • Preamble We, the sovereign Filipino people, imploring the aid of Almighty God, in order to build a just and humane society and establish a Government that shall embody our ideals and aspirations, promote the common good, conserve and develop our patrimony, and secure to ourselves and our posterity the blessings of independence and democracy under the rule of law and a regime of truth, justice, freedom, love, equality, and peace, do ordain and promulgate this Constitution. -

United States V. Rayburn House Office Building, Room 2113: a Midnight Raid on the Constitution Or Business As Usual?

Catholic University Law Review Volume 57 Issue 1 Fall 2007 Article 9 2007 United States v. Rayburn House Office Building, Room 2113: A Midnight Raid on the Constitution or Business as Usual? Brian Reimels Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Brian Reimels, United States v. Rayburn House Office Building, Room 2113: A Midnight Raid on the Constitution or Business as Usual?, 57 Cath. U. L. Rev. 293 (2008). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol57/iss1/9 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE UNITED STATES V. RAYBURN HOUSE OFFICE BUILDING, ROOM 2113: A MIDNIGHT RAID ON THE CONSTITUTION OR BUSINESS AS USUAL? Brian Reimels' "If men were angels, no government would be necessary."' A leather briefcase, cold hard cash (literally), and a telecommunications initiative in Africa only scratch the surface of one of Washington, D.C.'s most recent scandals. Bribery and quid pro quo, commonplace terms to describe the political landscape inside the Capital Beltway, have sparked movements to clean up the so-called "culture of corruption."2 But few cases have so enflamed the passions of constitutional scholars, congressmen, and the Justice Department than that of U.S. Representative William Jefferson.3 The Saturday night raid + J.D. Candidate, May 2008, The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law; B.A., Temple University. -

Can the President Cancel Or Postpone the General Election? ______

CAN THE PRESIDENT CANCEL OR POSTPONE THE GENERAL ELECTION? ____________________________________________________________ Summary: Unlike the primaries, which are governed by state law and take place on different dates across the country, federal law—which only Congress can change—sets November 3rd as the date of the general election. The president has no authority to change this date. The Constitution also significantly limits the ability of Congress to delay choosing the next president, even if it wants to—as under no circumstance can any president’s term be extended past noon on January 20th without amending the Constitution. ➢ The U.S. Constitution and Federal Law Require That the Election Be Completed by Early January Presidential elections in the United States are governed by a combination of the U.S. Constitution and federal, state, and local laws. The overall timing of the general presidential election is governed primarily by federal law, but also constrained by the Constitution.1 The actual mechanics of conducting the election are governed primarily by state and local law. The president is technically chosen by the Electoral College, which is composed of electors from each state.2 The Constitution provides that each state “shall appoint” its electors for president “in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct.” U.S. Const. art. II, § 1, cl. 2. That means that the fifty states and the District of Columbia have the ability, through their legislatures, to decide how to choose the electors who will participate in the Electoral College. All states have chosen to do so based on the popular vote—in other words, whichever candidate wins the most votes in the state on Election Day generally also wins the state’s electors.3 1 See the Appendix for a more detailed timeline. -

Az-Rep-20-2921

December 11, 2020 VIA EMAIL Representative Warren Petersen Arizona State Capitol Complex 1700 W Washington St., Rm. 208 Phoenix, AZ 85007 [email protected] Re: Public Records Request Dear Representative Petersen, Pursuant to the Arizona Public Records Law, A.R.S. §§ 39-121 et seq., American Oversight makes the following request for records. On November 30, 2020, members of the Arizona State Legislature met with President Trump’s personal lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, for an unofficial hearing in which participants aired unsubstantiated allegations regarding the integrity of the presidential election.1 Many of these same legislators have since called for a special session to directly appoint representatives to the Electoral College.2 American Oversight seeks records with the potential to shed light on whether or to what extent Arizona officials are acting at the behest of external political actors. Requested Records American Oversight requests that your office promptly produce the following records: All text message chains/conversations, or message chains/conversations on messaging applications similar in form to text messages (such as Signal, WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, Twitter DMs, etc.), between (a) Speaker Warren Petersen or his Chief of Staff, Michael Hunter, and (b) any of the external parties listed below. 1 Ryan Randazzo & Maria Polletta, Arizona GOP Lawmakers Hold Meeting on Election Outcome with Trump Lawyer Rudy Giuliani, Ariz. Republic (updated Nov. 30, 2020, 9:02 PM), https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/politics/elections/2020/11/30/republican- lawmakers-arizona-hold-meeting-rudy-giuliani/6468171002/. 2 Maria Polletta, ‘Cowardly’ Say Some Arizona Republicans of Leaders Following Closure of Legislature, Ariz. -

The Expulsion Powers of Congress: Justiciable Or Not

North Dakota Law Review Volume 46 Number 3 Article 6 1969 The Expulsion Powers of Congress: Justiciable or Not Terry C. Holter Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/ndlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Holter, Terry C. (1969) "The Expulsion Powers of Congress: Justiciable or Not," North Dakota Law Review: Vol. 46 : No. 3 , Article 6. Available at: https://commons.und.edu/ndlr/vol46/iss3/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Dakota Law Review by an authorized editor of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EXPULSION POWERS OF CONGRESS: JUSTICIABLE OR NOT This inquiry is concerned ultimately with one question. If either House of the United States Congress, purporting to act under Article 1, Section 5, of the United States Constitution, were to expel a mem- ber, would that member be able to seek judicial redress in a court of law? Or, to put the question differently, would such expulsion ever, under any circumstances, present a justiciable controversy? There appears to be no precedent on this particular issue, although at least two cases have referred to the question in a collateral man- ner.1 One thing is certain; when Congress moves to exclude a Mem- 2 ber-elect while purporting to act under its constitutional powers, there are some instances when an attempted exclusion will pre- sent a justiciable controversy.3 A most cursory examination of Powell v. -

Counting Ballots Until All Valid Votes Have Been Tallied

Nos. 20A53, 20A54 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ______________ JOSEPH B. SCARNATI III, ET AL., Applicants, v. KATHY BOOCKVAR, SECRETARY OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, ET AL., Respondents. _________ REPUBLICAN PARTY OF PENNSYLVANIA, Applicant, v. KATHY BOOCKVAR, SECRETARY OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, ET AL., Respondents. __________ On Applications to Stay the Mandate of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ________________ RESPONSE OF THE PENNSYLVANIA DEMOCRATIC PARTY RESPONDENTS ________ Lazar M. Palnick Clifford B. Levine 1216 Heberton Street Counsel of Record Pittsburgh, PA 15206 Alex M. Lacey (412) 661-3633 Dentons Cohen & Grigsby P.C. 625 Liberty Avenue Kevin Greenberg A. Michael Pratt Pittsburgh, PA 15222-3152 Adam Roseman (412) 297-4900 Greenberg Traurig, LLP [email protected] 1717 Arch Street, Suite 400 Philadelphia, PA 19103 (215) 988-7818 Counsel for Respondents Pennsylvania Democratic Party, Nilofer Nina Ahmad, Danilo Burgos, Austin Davis, Dwight Evans, Isabella Fitzgerald, Edward Gainey, Manuel M. Guzman, Jr., Jordan A. Harris, Arthur Haywood, Malcolm Kenyatta, Patty H. Kim, Stephen Kinsey, Peter Schweyer, Sharif Street, and Anthony H. Williams RULE 29.6 STATEMENT Pursuant to Rule 29.6 of the Rules of this Court, Respondent Pennsylvania Democratic Party states that it has no parent corporation and that there is no publicly held company that owns 10% or more of its stock. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page RULE 29.6 STATEMENT ............................................................................................................. -

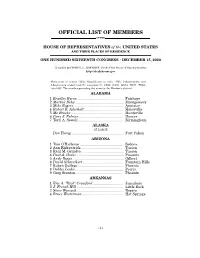

Official List of Members

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS • DECEMBER 15, 2020 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (233); Republicans in italic (195); Independents and Libertarians underlined (2); vacancies (5) CA08, CA50, GA14, NC11, TX04; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Bradley Byrne .............................................. Fairhope 2 Martha Roby ................................................ Montgomery 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................