Russia's Arctic Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Sea Route Cargo Flows and Infrastructure- Present State And

Northern Sea Route Cargo Flows and Infrastructure – Present State and Future Potential By Claes Lykke Ragner FNI Report 13/2000 FRIDTJOF NANSENS INSTITUTT THE FRIDTJOF NANSEN INSTITUTE Tittel/Title Sider/Pages Northern Sea Route Cargo Flows and Infrastructure – Present 124 State and Future Potential Publikasjonstype/Publication Type Nummer/Number FNI Report 13/2000 Forfatter(e)/Author(s) ISBN Claes Lykke Ragner 82-7613-400-9 Program/Programme ISSN 0801-2431 Prosjekt/Project Sammendrag/Abstract The report assesses the Northern Sea Route’s commercial potential and economic importance, both as a transit route between Europe and Asia, and as an export route for oil, gas and other natural resources in the Russian Arctic. First, it conducts a survey of past and present Northern Sea Route (NSR) cargo flows. Then follow discussions of the route’s commercial potential as a transit route, as well as of its economic importance and relevance for each of the Russian Arctic regions. These discussions are summarized by estimates of what types and volumes of NSR cargoes that can realistically be expected in the period 2000-2015. This is then followed by a survey of the status quo of the NSR infrastructure (above all the ice-breakers, ice-class cargo vessels and ports), with estimates of its future capacity. Based on the estimated future NSR cargo potential, future NSR infrastructure requirements are calculated and compared with the estimated capacity in order to identify the main, future infrastructure bottlenecks for NSR operations. The information presented in the report is mainly compiled from data and research results that were published through the International Northern Sea Route Programme (INSROP) 1993-99, but considerable updates have been made using recent information, statistics and analyses from various sources. -

Russia and the Eurasian Republics THIS REGION Spans the Continents of Europe and Asia

390-391 U5 CH14 UO TWIP-860976 3/15/04 5:21 AM Page 390 Unit Workers on the statue Russians in front of Motherland Calls, St. Basil’s Cathedral, Volgograd Moscow 224 390-391 U5 CH14 UO TWIP-860976 3/15/04 5:22 AM Page 391 RussiaRussia andand the the EurasianEurasian f you had to describe Russia RepublicsRepublics Iin one word, that word would be BIG! Russia is the largest country in the world in area. Its almost 6.6 million square miles (17 million sq. km) are spread across two continents—Europe and Asia. As you can imagine, such a large country faces equally large challenges. In 1991 Russia emerged from the Soviet Union as an independent country. Since then it has been struggling to unite its many ethnic groups, set up a demo- cratic government, and build a stable economy. ▼ Siberian tiger in a forest NGS ONLINE in eastern Russia www.nationalgeographic.com/education 225 392-401 U5 CH14 RA TWIP-860976 3/15/04 5:28 AM Page 392 REGIONAL ATLAS Focus on: Russia and the Eurasian Republics THIS REGION spans the continents of Europe and Asia. It includes Russia—the world’s largest country—and the neigh- boring independent republics of Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. Russia and the Eurasian republics cover about 8 million square miles (20.7 million sq. km). This is greater than the size of Canada, the United States, and Mexico combined. The Caspian Sea is actually a salt lake that lies at the base of the Caucasus Mountains in The Land Russia’s southwest. -

Expiry Notice

Expiry Notice 19 January 2018 London Stock Exchange Derivatives Expiration prices for IOB Derivatives Please find below expiration prices for IOB products expiring in January 2018: Underlying Code Underlying Name Expiration Price AFID AFI DEVELOPMENT PLC 0.1800 ATAD PJSC TATNEFT 58.2800 FIVE X5 RETAIL GROUP NV 39.2400 GAZ GAZPROM NEFT 23.4000 GLTR GLOBALTRANS INVESTMENT PLC 9.9500 HSBK JSC HALYK SAVINGS BANK OF KAZAKHSTAN 12.4000 HYDR PJSC RUSHYDRO 1.3440 KMG JSC KAZMUNAIGAS EXPLORATION PROD 12.9000 LKOD PJSC LUKOIL 67.2000 LSRG LSR GROUP 2.9000 MAIL MAIL.RU GROUP LIMITED 32.0000 MFON MEGAFON 9.2000 MGNT PJSC MAGNIT 26.4000 MHPC MHP SA 12.8000 MDMG MD MEDICAL GROUP INVESTMENTS PLC 10.5000 MMK OJSC MAGNITOGORSK IRON AND STEEL WORKS 10.3000 MNOD MMC NORILSK NICKEL 20.2300 NCSP PJSC NOVOROSSIYSK COMM. SEA PORT 12.9000 NLMK NOVOLIPETSK STEEL 27.4000 NVTK OAO NOVATEK 128.1000 OGZD GAZPROM 5.2300 PLZL POLYUS PJSC 38.7000 RIGD RELIANCE INDUSTRIES 28.7000 RKMD ROSTELEKOM 6.9800 ROSN ROSNEFT OJSC 5.7920 SBER SBERBANK 18.6900 SGGD SURGUTNEFTEGAZ 5.2450 SMSN SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS CO 1148.0000 SSA SISTEMA JSFC 4.4200 SVST PAO SEVERSTAL 16.8200 TCS TCS GROUP HOLDING 19.3000 TMKS OAO TMK 5.4400 TRCN PJSC TRANSCONTAINER 8.0100 VTBR JSC VTB BANK 1.9370 Underlying code Underlying Name Expiration Price D7LKOD YEAR 17 DIVIDEND LUKOIL FUTURE 3.2643 YEAR 17 DIVIDEND MMC NORILSK NICKEL D7MNOD 1.8622 FUTURE D7OGZD YEAR 17 DIVIDEND GAZPROM FUTURE 0.2679 D7ROSN YEAR 17 DIVIDEND ROSNEFT FUTURE 0.1672 D7SBER YEAR 17 DIVIDEND SBERBANK FUTURE 0.3980 D7SGGD YEAR 17 DIVIDEND SURGUTNEFTEGAZ FUTURE 0.1000 D7VTBR YEAR 17 DIVIDEND VTB BANK FUTURE 0.0414 Members are asked to note that reports showing exercise/assignments should be available by approx. -

Siberia and the Russian Far East in the 21St Century: Scenarios of the Future

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 11 (2017 10) 1669-1686 ~ ~ ~ УДК 332.1:338.1(571) Siberia and the Russian Far East in the 21st Century: Scenarios of the Future Valerii S. Efimov and Alla V. Laptevа* Siberian Federal University 79 Svobodny, Krasnoyarsk, 660041, Russia Received 07.09.2017, received in revised form 07.11.2017, accepted 14.11.2017 The article presents a study of variants of possible future for Siberia and Russian Far East up until 2050. The authors consider the global trends that are likely to determine the situation of Russia and the Siberian macro-region in the long term. It is shown that the demand for natural resources of Siberia and Russian Far East will be determined by the economic development of Asian countries, the processes of urbanization and the growth of urban “middle class”. When determining possible scenarios, the authors use a method of conceptual scenario planning that was developed under the framework of foresight technology. Three groups of scenario factors became the basis for determining scenarios: external constant conditions, external variable factors, internal variable factors. Combinations of scenario factors set the field for the possible variants of the future of Siberia and Russian East. The article describes four key scenarios: “Broad international cooperation”, “Exclusive partnership”, “Optimization of the country”, “Retention of territory”. For each of them the authors provide “the image of the future” (including the main features of international cooperation, economic and social development), as well as the quantitative estimation of population and GDP dynamics: • “Broad international cooperation” – the population of Russia will increase by 15.7 % from 146.5 million in 2015 to 169.5 million in 2050; Russia’s GDP will grow by 3.4 times – from 3.8 trillion dollars (PPP) in 2015 to 12.8 trillion dollars in 2050. -

FY2020 Financial Results

Norilsk Nickel 2020 Financial Results Presentation February 2021 Disclaimer The information contained herein has been prepared using information available to PJSC MMC Norilsk Nickel (“Norilsk Nickel” or “Nornickel” or “NN”) at the time of preparation of the presentation. External or other factors may have impacted on the business of Norilsk Nickel and the content of this presentation, since its preparation. In addition all relevant information about Norilsk Nickel may not be included in this presentation. No representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the accuracy, completeness or reliability of the information. Any forward looking information herein has been prepared on the basis of a number of assumptions which may prove to be incorrect. Forward looking statements, by the nature, involve risk and uncertainty and Norilsk Nickel cautions that actual results may differ materially from those expressed or implied in such statements. Reference should be made to the most recent Annual Report for a description of major risk factors. There may be other factors, both known and unknown to Norilsk Nickel, which may have an impact on its performance. This presentation should not be relied upon as a recommendation or forecast by Norilsk Nickel. Norilsk Nickel does not undertake an obligation to release any revision to the statements contained in this presentation. The information contained in this presentation shall not be deemed to be any form of commitment on the part of Norilsk Nickel in relation to any matters contained, or referred to, in this presentation. Norilsk Nickel expressly disclaims any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the contents of this presentation. -

The Russia You Never Met

The Russia You Never Met MATT BIVENS AND JONAS BERNSTEIN fter staggering to reelection in summer 1996, President Boris Yeltsin A announced what had long been obvious: that he had a bad heart and needed surgery. Then he disappeared from view, leaving his prime minister, Viktor Cher- nomyrdin, and his chief of staff, Anatoly Chubais, to mind the Kremlin. For the next few months, Russians would tune in the morning news to learn if the presi- dent was still alive. Evenings they would tune in Chubais and Chernomyrdin to hear about a national emergency—no one was paying their taxes. Summer turned to autumn, but as Yeltsin’s by-pass operation approached, strange things began to happen. Chubais and Chernomyrdin suddenly announced the creation of a new body, the Cheka, to help the government collect taxes. In Lenin’s day, the Cheka was the secret police force—the forerunner of the KGB— that, among other things, forcibly wrested food and money from the peasantry and drove some of them into collective farms or concentration camps. Chubais made no apologies, saying that he had chosen such a historically weighted name to communicate the seriousness of the tax emergency.1 Western governments nod- ded their collective heads in solemn agreement. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank both confirmed that Russia was experiencing a tax collec- tion emergency and insisted that serious steps be taken.2 Never mind that the Russian government had been granting enormous tax breaks to the politically connected, including billions to Chernomyrdin’s favorite, Gazprom, the natural gas monopoly,3 and around $1 billion to Chubais’s favorite, Uneximbank,4 never mind the horrendous corruption that had been bleeding the treasury dry for years, or the nihilistic and pointless (and expensive) destruction of Chechnya. -

Fertility and Women Life Expectancy in Krasnoyarsk Territory: Social and Economic Transition and Intraregional Demographic Response

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 11 (2016 9) 2742-2755 ~ ~ ~ УДК [314.1/.4+612.663]-055.2(571.51) Fertility and Women Life Expectancy in Krasnoyarsk Territory: Social and Economic Transition and Intraregional Demographic Response Marina E. Rublevaa*, Vladimir F. Mazharovb,c, Vladimir L. Gavrikova and Rem G. Khleboprosa,d a Siberian Federal University 79 Svobodny, Krasnoyarsk, 660041, Russia b Research Institute for Complex Problems of Hygiene and Occupational Diseases Novokuznetsk-Krasnoyarsk c Krasnoyarsk State Medical University named after Prof. V.F. Voino-Yasenetsky 1 Partizan Zheleznyak Str., Krasnoyarsk, 660022, Russia d International Scientific Research Center for Extreme Conditions of Organism Krasnoyarsk Scientific Center SB RAS 50 Akademgorodok, Krasnoyarsk, 660036, Russia Received 06.07.2016, received in revised form 28.08.2016, accepted 07.10.2016 Demographic processes are often studied one-dimensionally, i.e. the processes are described through dynamics of one demographic parameter. Meanwhile, relationships between different demographic parameters are of general interest. Tolstikhina et al. (Tolstikhina, Gavrikov, Khlebopros, Okhonin, 2013) showed that fertility and life expectancy are negatively correlated among countries of the world. The same relationship of fertility and life expectancy has been studied by us in this research at an intraregional level through the example of Krasnoyarsk Territory. The demographic data from 1995 to 2013 have been used to describe dynamics of the relationship. The main method used was weighted fitting of the data by a linear function, with weights being the population of the territory administrative regions. No statistically significant relationship between the fertility and female life expectancy has been found in 1995, i.e. -

Taltheilei Houses, Lithics, and Mobility

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2012-09-06 Taltheilei houses, lithics, and mobility Pickering, Sean Joseph Pickering, S. J. (2012). Taltheilei houses, lithics, and mobility (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27975 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/177 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Taltheilei Houses, Lithics, and Mobility by Sean J. Pickering A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2012 © Sean J. Pickering 2012 Abstract The precontact subsistence-settlement strategy of Taltheilei tradition groups has been interpreted by past researchers as representing a high residential mobility forager system characterized by ephemeral warm season use of the Barrenlands environment, while hunting barrenground caribou. However, the excavation of four semi-subterranean house pits at the Ikirahak site (JjKs-7), in the Southern Kivalliq District of Nunavut, has challenged these assumptions. An analysis of the domestic architecture, as well as the morphological and spatial attributes of the excavated lithic artifacts, has shown that some Taltheilei groups inhabited the Barrenlands environment during the cold season for extended periods of time likely subsisting on stored resources. -

Russia: the Impact of Climate Change to 2030: Geopolitical Implications

This paper does not represent US Government views. This page is intentionally kept blank. This paper does not represent US Government views. This paper does not represent US Government views. Russia: The Impact of Climate Change to 2030: Geopolitical Implications Prepared jointly by CENTRA Technology, Inc., and Scitor Corporation The National Intelligence Council sponsors workshops and research with nongovernmental experts to gain knowledge and insight and to sharpen debate on critical issues. The views expressed in this report do not reflect official US Government positions. CR 2009-16 September 2009 This paper does not represent US Government views. This paper does not represent US Government views. This page is intentionally kept blank. This paper does not represent US Government views. This paper does not represent US Government views. Scope Note Following the publication in 2008 of the National Intelligence Assessment on the National Security Implications of Global Climate Change to 2030, the National Intelligence Council (NIC) embarked on a research effort to explore in greater detail the national security implications of climate change in six countries/regions of the world: India, China, Russia, North Africa, Mexico and the Caribbean, and Southeast Asia and the Pacific Island States. For each country/region we have adopted a three-phase approach. • In the first phase, contracted research explores the latest scientific findings on the impact of climate change in the specific region/country. For Russia, the Phase I effort was published as a NIC Special Report: Russia: Impact of Climate Change to 2030, A Commissioned Research Report (NIC 2009-04, April 2009). • In the second phase, a workshop or conference composed of experts from outside the Intelligence Community (IC) determines if anticipated changes from the effects of climate change will force inter- and intra-state migrations, cause economic hardship, or result in increased social tensions or state instability within the country/region. -

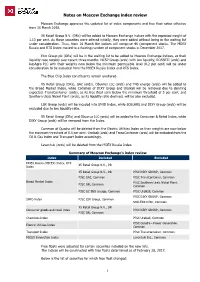

Notes on Moscow Exchange Index Review

Notes on Moscow Exchange index review Moscow Exchange approves the updated list of index components and free float ratios effective from 16 March 2018. X5 Retail Group N.V. (DRs) will be added to Moscow Exchange indices with the expected weight of 1.13 per cent. As these securities were offered initially, they were added without being in the waiting list under consideration. Thus, from 16 March the indices will comprise 46 (component stocks. The MOEX Russia and RTS Index moved to a floating number of component stocks in December 2017. En+ Group plc (DRs) will be in the waiting list to be added to Moscow Exchange indices, as their liquidity rose notably over recent three months. NCSP Group (ords) with low liquidity, ROSSETI (ords) and RosAgro PLC with their weights now below the minimum permissible level (0.2 per cent) will be under consideration to be excluded from the MOEX Russia Index and RTS Index. The Blue Chip Index constituents remain unaltered. X5 Retail Group (DRs), GAZ (ords), Obuvrus LLC (ords) and TNS energo (ords) will be added to the Broad Market Index, while Common of DIXY Group and Uralkali will be removed due to delisting expected. TransContainer (ords), as its free float sank below the minimum threshold of 5 per cent, and Southern Urals Nickel Plant (ords), as its liquidity ratio declined, will be also excluded. LSR Group (ords) will be incuded into SMID Index, while SOLLERS and DIXY Group (ords) will be excluded due to low liquidity ratio. X5 Retail Group (DRs) and Obuvrus LLC (ords) will be added to the Consumer & Retail Index, while DIXY Group (ords) will be removed from the Index. -

Yamalia English Language Teachers’ Association

Yamalia English Language Teachers’ Association YAMALIA – THE BACK OF BEYOND A Series of English Lessons in Yamalia Studies Edited by Eugene Kolyadin Yelena Gorshkova Oxana Sokolenko Irina Kolyadina Based on teaching materials created by Alevtina Andreyeva (Salemal), Svetlana Bochkaryova (Salekhard), Natalia Bordzilovskaya (Noyabrsk), Natalia Derevyanko (Noyabrsk), Yelena Gorshkova (Gubkinsky), Olga Grinkevich (Muravlenko), Tamara Khokhlova (Noyabrsk), Anzhelika Khokhlyutina (Muravlenko), Irina Kolyadina (Gubkinsky), Yulia Rudakova (Nadym), Irina Rusina (Noyabrsk), Diana Saitova (Nadym), Yulia Sibulatova (Nadym), Natalia Soip (Nadym), Yelena Ten (Nadymsky district), Natalya Togo (Nyda), Olga Yelizarova (Noyabrsk), Alfiya Yusupova (Muravlenko), Irina Zinkovskaya (Nadym) Phonetic and Listening Comprehension tapescripts sounded by Svetlana Filippova, Associate Professor, Nizhny Novgorod Dobrolyubov State Linguistics University Gubkinsky Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug 2015 2 Yamalia English Language Teachers’ Association Yamalia – the Back of Beyond. A Series of English Lessons in Yamalia Studies: Сборник учебно-методических материалов для проведения учебных занятий по регионоведению Ямало-Ненецкого автономного округа на английском языке в 8 – 11 классах средних общеобразовательных организаций / Под ред. Е.А. Колядина, Е.А. Горшковой, И.А. Колядиной, О.Б. Соколенко. – Губкинский, 2015. – 82 c. – На англ. яз. Yamalia – the Back of Beyond 3 FOREWORD1 The booklet you are holding in your hands now is a fruit of collaboration of tens of Yamalia teachers of English from different parts of the okrug. The main goal of the authors’ team was to summarise the best practices developed by the okrug educators as well as their expertise in teaching regional studies and disseminate that all around Yamalia. We think that it is a brilliant idea to arm our teachers with ready-made though flexible to adaptation lessons to teach students to different aspects of life in our lands in English. -

Helicobacter Pylori's Historical Journey Through Siberia and the Americas

Helicobacter pylori’s historical journey through Siberia and the Americas Yoshan Moodleya,1,2, Andrea Brunellib,1, Silvia Ghirottoc,1, Andrey Klyubind, Ayas S. Maadye, William Tynef, Zilia Y. Muñoz-Ramirezg, Zhemin Zhouf, Andrea Manicah, Bodo Linzi, and Mark Achtmanf aDepartment of Zoology, University of Venda, Thohoyandou 0950, Republic of South Africa; bDepartment of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, University of Ferrara, 44121 Ferrara, Italy; cDepartment of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Ferrara, 44121 Ferrara, Italy; dDepartment of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Research Institute for Physical-Chemical Medicine, 119435 Moscow, Russia; eDepartment of Diagnostic and Operative Endoscopy, Pirogov National Medical and Surgical Center, 105203 Moscow, Russia; fWarwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, United Kingdom; gLaboratorio de Bioinformática y Biotecnología Genómica, Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas, Unidad Profesional Lázaro Cárdenas, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, 11340 Mexico City, Mexico; hDepartment of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, United Kingdom; and iDepartment of Biology, Division of Microbiology, Friedrich Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg, 91058 Erlangen, Germany Edited by Daniel Falush, University of Bath, Bath, United Kingdom, and accepted by Editorial Board Member W. F. Doolittle April 30, 2021 (received for review July 22, 2020) The gastric bacterium Helicobacter pylori shares a coevolutionary speakers). However, H. pylori’s presence, diversity, and structure history with humans that predates the out-of-Africa diaspora, and in northern Eurasia are still unknown. This vast region, hereafter the geographical specificities of H. pylori populations reflect mul- Siberia, extends from the Ural Mountains in the west to the tiple well-known human migrations. We extensively sampled H.