Federal Distribution Formulas Should Be Changed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Florida Traveler's Guide

Florida’s Major Highway Construction Projects: April - June 2018 Interstate 4 24. Charlotte County – Adding lanes and resurfacing from south of N. Jones 46. Martin County – Installing Truck Parking Availability System for the south- 1. I-4 and I-75 interchange -- Hillsborough County – Modifying the eastbound Loop Road to north of US 17 (4.5 miles) bound Rest Area at mile marker 107, three miles south of Martin Highway / and westbound I-4 (Exit 9) ramps onto northbound I-75 into a single entrance 25. Charlotte County – Installing Truck Parking Availability System for the SR 714 (Exit 110), near Palm City; the northbound Rest Area at mile marker point with a long auxiliary lane. (2 miles) northbound and southbound Weigh Stations at mile marker 158 106, four miles south of Martin Highway /SR 714 (Exit 110) near Palm City; the southbound Weigh-in-Motion Station at mile marker 113, one mile south of 2. Polk County -- Reconstructing the State Road 559 (Ex 44) interchange 26. Lee County -- Replacing 13 Dynamic Message Signs from mile marker 117 to mile marker 145 Becker Road (Exit 114), near Palm City; and the northbound Weigh-in-Motion 3. Polk County -- Installing Truck Parking Availability System for the eastbound Station at mile marker 92, four miles south of Bridge Road (Exit 96), near 27. Lee County – Installing Truck Parking Availability System for the northbound and westbound Rest Areas at mile marker 46. Hobe Sound and southbound Rest Areas at mile marker 131 4. Polk County -- Installing a new Fog/Low Visibility Detection System on 47. -

Federal Register/Vol. 65, No. 233/Monday, December 4, 2000

Federal Register / Vol. 65, No. 233 / Monday, December 4, 2000 / Notices 75771 2 departures. No more than one slot DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION In notice document 00±29918 exemption time may be selected in any appearing in the issue of Wednesday, hour. In this round each carrier may Federal Aviation Administration November 22, 2000, under select one slot exemption time in each SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION, in the first RTCA Future Flight Data Collection hour without regard to whether a slot is column, in the fifteenth line, the date Committee available in that hour. the FAA will approve or disapprove the application, in whole or part, no later d. In the second and third rounds, Pursuant to section 10(a)(2) of the than should read ``March 15, 2001''. only carriers providing service to small Federal Advisory Committee Act (Pub. hub and nonhub airports may L. 92±463, 5 U.S.C., Appendix 2), notice FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: participate. Each carrier may select up is hereby given for the Future Flight Patrick Vaught, Program Manager, FAA/ to 2 slot exemption times, one arrival Data Collection Committee meeting to Airports District Office, 100 West Cross and one departure in each round. No be held January 11, 2000, starting at 9 Street, Suite B, Jackson, MS 39208± carrier may select more than 4 a.m. This meeting will be held at RTCA, 2307, 601±664±9885. exemption slot times in rounds 2 and 3. 1140 Connecticut Avenue, NW., Suite Issued in Jackson, Mississippi on 1020, Washington, DC, 20036. November 24, 2000. e. Beginning with the fourth round, The agenda will include: (1) Welcome all eligible carriers may participate. -

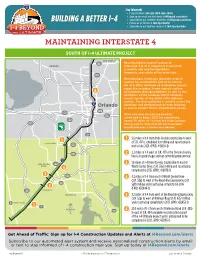

View Or Download a Handout

Stay Informed: » Project Hotline: 844-ULT-INFO (858-4636) » Sign up for email and text alerts at i4Beyond.com/alerts BUILDING A BETTER I-4 » Subscribe to our monthly newsletter at i4Beyond.com/news » Follow us on Twitter at fdot.tips/twitter » Subscribe to our YouTube channel at fdot.tips/youtube MAINTAINING INTERSTATE 4 SOUTH OF I-4 ULTIMATE PROJECT Longwood 434 Resurfacing the asphalt surface of Apopka Interstate 4 (I-4) is important to maintain a smooth ride and the durability, longevity, and safety of the interstate. 436 Resurfacing is necessary when the asphalt surface has reached the end of its service life or if other methods of restoration cannot repair the roadway. A new asphalt surface 6 will improve driving conditions as well as the aesthetics of the roadway. FDOT conducts annual surveys of the entire state highway system. The data collected is used to assess the Orlando condition and performance of each roadway as well as predict future rehabilitation needs. 50 408 408 Once two new resurfacing projects scheduled to begin 2021 are completed, 435 nearly 70 miles of I-4 from the Polk-Osceola 429 county line to Interstate 95 will have been resurfaced over a seven-year period. 441 5 1 5.6 miles of I-4 from Polk-Osceola county line to west Doctor Phillips of S.R. 417 is scheduled for milling and resurfacing in 482 mid to late 2021. (FPID: 443958-1) 528 2 2.2 miles of I-4 west of S.R. 417 to the Osceola County line is in good shape and not currently programmed. -

Parramore and the Interstate 4: a World Torn Asunder (1880-1980) Yuri K

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses Summer 2015 Parramore and the Interstate 4: A World Torn Asunder (1880-1980) Yuri K. Gama Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the African American Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Recommended Citation Gama, Yuri K., "Parramore and the Interstate 4: A World Torn Asunder (1880-1980)" (2015). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 71. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/71 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgments 04 Abstract 06 Introduction 07 Chapter I: Social Black History and Racial Segregation 14 1865 to 1920 14 1920 to 1945 21 1945 to 1970 30 Chapter II: History of American Urban Sprawl 38 Transportation Development 42 Housing Development 49 Chapter III: Racial Segregation in Florida 60 1860 - 1920 60 1920 – 1950 67 2 1950 – 1980 71 Chapter IV: The Highway System and the I-4 Construction 78 United States’ Roads and Highways 78 Wartime and Postwar Defense Expenditures in a Growing Florida 86 Florida’s Roads and Highways 89 Orlando and Interstate 4 91 Chapter V: Parramore and the I-4 98 Racial Segregation and Parramore’s Foundation 98 Uneven Development and Parramore’s Decline 108 Parramore and the Social Impact of I-4 (1957-1980) 113 Conclusion 122 Bibliography 134 Appendix A 162 Appendix B 163 3 Dedicated to all those who struggle against any form of racial oppression and social inequality. -

FDOT and NTPEP Pavement Marking Materials Test Decks Project Overview

Florida Department of Transportation FDOT and NTPEP Pavement Marking Materials Test Decks Project Overview FDOT Office State Materials Office Report Number EXP-I-4 Authors Nikita L. Reed Date of Publication March 2017 Florida Department of Transportation About NTPEP The National Transportation Product Evaluation Program (NTPEP) provides product evaluation and plant inspection services. Product evaluation ensures that products that are commonly used by state Departments of Transportation (DOTs) are tested in accordance with national standards. This collaboration between NTPEP, state DOTs, and product manufacturers reduces duplication of effort by DOTs and provides a single source of testing for manufacturers. To learn more, visit www.ntpep.org. Project Overview The primary purpose for pavement marking materials, also known as traffic striping, is delineation of traffic which is critical to motorist safety. Traffic striping, like all paints, will eventually deteriorate. There are several factors that contribute to how quickly this process occurs such as (1) the type of road the striping was used on, (2) the traffic volume on the road, (3) weather conditions and (4) the quality of the product itself. Re- striping a road after pavement markings have lost their effectiveness has a financial cost and can be disruptive to the traveling public. The materials that work best are those that are long-lasting and most effective in helping drivers to stay in their lanes while traveling during the day, nighttime and wet conditions. In October 2009, FDOT became part of a rotating group of state highway agencies that perform field testing to evaluate the performance of pavement marking materials (PMM) for NTPEP. -

I-4 Florida's Regional Advanced Mobility Elements Project

I-4 Florida’s Regional Advanced Mobility Elements Project FDOT Connected and Automated Vehicles Program I-4 FRAME Project 1 2 3 4 5 What Why Where How When I-4 Florida’s Regional Advanced Mobility Elements Project FDOT Connected and Automated Vehicles Program 1 What is the I-4 Florida’s Regional Advanced Mobility Elements Project? The Florida Department of Transportation’s (FDOT) vision is to promote safety, mobility and innovation. FDOT developed the I-4 FRAME project to make your trip more reliable and safer. I-4 FRAME through Connected Vehicle (CV) and Intelligent Transportation System (ITS) technologies will leverage vehicle-to-infrastructure and vehicle-to-vehicle technologies to reduce crashes and improve mobility. How I-4 Florida’s Regional Advanced Mobility Elements Project FDOT Connected and Automated Vehicles Program 2 Why do we need the I-4 FRAME Project? Interstate-4 (I-4) is a vital artery for economic activities in Florida, connecting the east and west coasts and the Tampa Bay and Orlando metropolitan regions. Orlando received 75 million annual visitors in 2018 & is America’s most visited destination. More than 150,700 vehicles traveling daily I-4 experiences severe mobility issues due to frequent crashes and recurring congestion. Between 2016 and 2018, 45 fatal crashes and 2,081 injury crashes. For the Traffic Homicide investigation the average I-4 closure is 4 hours. How I-4 averaged two lane-closure events per day One full directional closure every 11 days in 2018. I-4 Florida’s Regional Advanced Mobility Elements Project FDOT Connected and Automated Vehicles Program 2 Why do we need the I-4 FRAME project? Crash Severity 2016 2017 2018 Total Fatality 16 12 17 45 Injury 642 712 727 2,081 Property Damage Only 1,586 1,936 1,771 5,293 Grand Total 2,244 2,660 2,515 7,419 Location of major incidents that close down I-4 on a regular basis. -

Advancing Racial Equity Through Highway Reconstruction

VANDERBILT LAW REVIEW ________________________________________________________________________ VOLUME 73 OCTOBER 2020 NUMBER 5 ________________________________________________________________________ ARTICLES “White Men’s Roads Through Black Men’s Homes”*: Advancing Racial Equity Through Highway Reconstruction Deborah N. Archer** Racial and economic segregation in urban communities is often understood as a natural consequence of poor choices by individuals. In reality, racially and economically segregated cities are the result of many factors, * “White men’s roads through black men’s homes” was the mantra of a coalition led by Reginald M. Booker and Sammie Abbott in opposition to highway development in Washington, D.C. See Harry Jaffe, The Insane Highway Plan that Would Have Bulldozed DC’s Most Charming Neighborhoods, WASHINGTONIAN (Oct. 21, 2015), https://www.washingtonian.com/2015/10/21/the- insane-highway-plan-that-would-have-bulldozed-washington-dcs-most-charming-neighborhoods/ [https://perma.cc/6YCR-PKKR] (discussing the campaign to halt the building of highways in Washington, D.C.). ** Associate Professor of Clinical Law and Co-Faculty Director of the Center on Race, Inequality, and the Law, New York University School of Law. I thank Rachel Barkow, Richard Buery, Audrey McFarlane, Michael Pinard, Russell Robinson, Sarah Schindler, Tony Thompson, Kele Williams, and Katrina Wyman for helpful comments on earlier drafts. I also appreciate the insights I received from participants of faculty workshops at Brooklyn Law School and the University of Miami School of Law and participants at the 2019 Clinical Law Review Workshop at NYU Law School. I am grateful to Nelson Castano, Anna Applebaum, Michael Milov-Cordoba, and Rachel Sommer for their research assistance and to Sarah Jaramillo for her constant support of my research. -

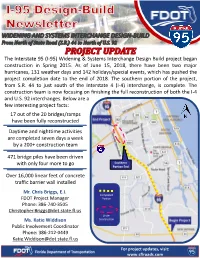

(I-95) Widening & Systems Interchange Design Build Project

The Interstate 95 (I-95) Widening & Systems Interchange Design Build project began construction in Spring 2015. As of June 15, 2018, there have been two major hurricanes, 131 weather days and 142 holidays/special events, which has pushed the project completion date to the end of 2018. The southern portion of the project, from S.R. 44 to just south of the Interstate 4 (I-4) interchange, is complete. The construction team is now focusing on finishing the full reconstruction of both the I-4 and U.S. 92 interchanges. Below are a few interesting project facts: 17 out of the 20 bridges/ramps have been fully reconstructed Daytime and nighttime activities are completed seven days a week by a 200+ construction team 471 bridge piles have been driven with only four more to go Southern Portion End Over 16,000 linear feet of concrete traffic barrier wall installed Mr. Chris Briggs, E.I. Completed FDOT Project Manager Portion Phone: 386-740-3505 [email protected] Under Ms. Katie Widdison Construction Public Involvement Coordinator Phone: 386-212-0449 [email protected] For project updates, visit: www.cflroads.com 2015 2018 1. Spruce Creek is 200 feet wide in this location 2. The new bridges are approximately 1,160 feet long 3. Boat access remained unaffected throughout construction 4. A 10-foot shoulder was built on both the inside and the outside of each new bridge to allow for emergency stops 5. Traffic was shifted to the new bridges in April 2017 For project updates, visit: www.cflroads.com 2015 2018 1. -

Hilton Orlando/Altamonte Springs Directions

HILTON ORLANDO/ALTAMONTE SPRINGS DIRECTIONS FROM AIRPORT TAKE STATE ROAD 436 NORTH FOR APPROXIMATELY 3 MILES. ON RIGHT WILL BE ENTRANCE TO STATE ROAD 408 WEST TO INTERSTATE 4. TAKE INTERSTATE 4 EAST TO EXIT 48 (STATE ROAD 436) TURN RIGHT OFF EXIT, STAY IN RIGHT LANE, GO TO THE FIRST TRAFFIC LIGHT AND TURN RIGHT. HOTEL IS ¼ MILE DOWN ON RIGHT. FROM EAST COAST VIA 528 TAKE 528 WEST TO 417 NORTH, THEN 408 WEST TO INTERSTATE 4. TAKE INTERSTATE 4 EAST TO EXIT 48. (STATE ROAD 436) TURN RIGHT OFF EXIT, STAY IN RIGHT LANE, GO TO THE FIRST TRAFFIC LIGHT AND TURN RIGHT. HOTEL IS ¼ MILE DOWN ON RIGHT. FROM TAMPA AND DISNEY AREA TAKE INTERSTATE 4 EAST TO EXIT 48 (STATE ROAD 436). TURN RIGHT OFF EXIT, STAY IN RIGHT LANE, GO TO THE FIRST TRAFFIC LIGHT AND TURN RIGHT. HOTEL IS ¼ MILE DOWN ON RIGHT. FROM DAYTONA BEACH TAKE INTERSTATE 4 WEST TO EXIT 48 (STATE ROAD 436). TURN LEFT OFF EXIT, GO OVER BRIDGE, AND GET IN FAR RIGHT LANE. GO ONE BLOCK TO FIRST TRAFFIC LIGHT AND TURN RIGHT. HOTEL IS ¼ MILE DOWN ON RIGHT. FROM GAINESVILLE/OCALA TAKE INTERSTATE 75 SOUTH TO THE FLORIDA TURNPIKE (THERE IS A TOLL). TAKE THE FLORIDA TURNPIKE SOUTH TO STATE ROAD 408 (EXIT #265 EAST/WEST EXPRESSWAY) GO EAST. TAKE STATE ROAD 408 TO INTERSTATE 4 EAST TO EXIT 48 (STATE ROAD 436). TURN RIGHT TO EXIT, STAY IN RIGHT LANE, FIRST LIGHT TURN RIGHT. HOTEL IS ¼ MILE DOWN ON RIGHT. FROM MIAMI TAKE FLORIDA TURNPIKE NORTH (THERE IS A TOLL) TO EXIT 259 INTERSTATE 4 EAST. -

Interstate Methodology and Data Everquote Analyzed Interstate

Interstate Methodology and Data EverQuote analyzed interstate fatalities using raw data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Fatality Analysis Report System from the last six years (2010–2015) and found fatality rates based on the highway lengths. We also compared that to data from EverQuote’s safe-driving app, EverDrive. That data represents over 6 million trips and 80 million miles of driving. Phone use is measured by a driver’s phone motion while driving. While it’s difficult to say for sure what impacts these crashes, there are some commonalities between the most lethal interstates, including high traffic volume, risky driving habits and a lack of distracted driving legislation. Distracted driving fatalities increased 8.8% in 2015 and distraction is believed to be responsible for 10% of all fatal crashes. For the first six months of 2016, traffic fatalities were also up 10.4% compared to the first half of last year. EverDrive data shows that US drivers are distracted by their phones on 31% of all drives: ● 11% of drives have a distraction of one minute or longer while driving in a moving vehicle ● 29% of distractions occur at speeds over 56 mph The average number of times per trip that drivers use their phones nationwide is 1.1. Drivers are, on average, driving .4 miles distracted every 11 miles. You can find that information in our “Confused State of Distracted Driving Report” and Infographic Florida: Three of the most dangerous interstate highways run through the state of Florida (I-4, I-95, I-10). Our EverDrive data found that Florida drivers use their phone on average 1.4 phone uses per trip and the state ranks 2nd worst nationally for phone use while driving. -

Florida Department of Transportation/Florida's Turnpike

Florida Department of Transportation/Florida’s Turnpike Enterprise RON DESANTIS Turkey Lake Service Plaza | Mile Post 263 | Bldg. #5315 KEVIN J. THIBAULT, P.E. GOVERNOR P.O. Box 613069, Ocoee, Florida 34761 SECRETARY For Immediate Release Contact: Maria Parada April 2, 2021 (407) 264-3069 | [email protected] Central and West Central Florida Weekly Lane Closures and Work Zone Advisory OCOEE, Fla. – Florida’s Turnpike Enterprise announces lane closures and work zone information for construction and maintenance projects in Central Florida beginning Sunday, April 4. Motorists should drive with caution through work zones and adhere to posted detour signs and speed limits. Please pay special attention to the closures noted in red. Regularly scheduled construction and maintenance-related lane closures on Florida’s Turnpike operated roads are suspended for the Good Friday & Easter holiday from 6 a.m. Friday, April 2, to 10 p.m. Sunday, April 4, unless otherwise indicated below. CENTRAL TURNPIKE MAINLINE/SR 91 (Mileposts 188 to 240) OSCEOLA COUNTY ALL-ELECTRONIC TOLLING (AET) CONVERSION PROJECT PHASE 8 ON CENTRAL TURNPIKE MAINLINE/SR 91 FROM THE LANTANA TOLL PLAZA TO THE THREE LAKES TOLL PLAZA (MILEPOSTS 88-236) Northbound and southbound Florida’s Turnpike/SR 91 from north of Canoe Creek Service Plaza to Three Lakes Toll Plaza (Milepost 236) Overnight single lane closure, 10 p.m. Sunday, April 4, to 6 a.m. Monday, April 5. Overnight single lane closures, 8:30 p.m. to 6 a.m., Monday, April 5, and nightly through Thursday, April 8. PROJECT DESCRIPTION: Work consists of providing all labor, materials, equipment, and incidentals necessary for the conversion of Central Turnpike Mainline/SR 91 to an All-Electronic Tolling (AET) collection system from milepost 88 to milepost 236. -

INTERSTATE 4 - FLORIDA Florida Department of Transportation District 5 State Highway Maintenance

INTERSTATE 4 - FLORIDA Florida Department of Transportation District 5 State Highway Maintenance DBi Services has provided performance-based asset maintenance services for FDOT Districts 5 and 1 in Volusia, Seminole, Orange, Osceola and Polk Counties along the I-4 Corridor since 2012. This project consists of 740 lane miles of limited access interstate and 120 raised structures. Included in the I-4 contract are operations and maintenance of two of the oldest rest areas in the state, as well as oversight of four Florida Department of Corrections (DoC) maintenance crews. In 2014 FDOT began construction of the I-4 Ultimate Public Private Partnership Project, which consists of a 21-mile stretch of roadway in the center of DBi Services’ project areas. This effectively splits our projects into two very distinct parts. As a result, we have to maintain close coordination with the construction contractor regarding road closures and incident response. Project Highlights Incident and Emergency response is an integral part of this contract. DBi Services is responsible for 24/7/365 accident and emergency response throughout the project corridor including coordination of resources working with the FDOT traffic control centers, as well as all police agencies and Traffic Incident Management Systems (TIMS). DBi Services has the knowledge and experience to respond to multiple accidents at the same time. On January 31, 2014 at 2:10 pm the Regional Traffic Management Center recorded 10 single different accidents on I-4 from Lake Mary to SR 434 and requested assistance from DBi Services. Our incident responders arrived within 30 minutes and the roadway was clear with traffic flowing by 3:05 pm.