Radiator Springs:" Industry Dynamics, Sunk Costs, and Spatial Demand Shifts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CODE of COLORADO REGULATIONS 8 CCR 1507-25 Division of State Patrol

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY Division of State Patrol RULES AND REGULATIONS CONCERNING THE PERMITTING, ROUTING & TRANSPORTATION OF HAZARDOUS AND NUCLEAR MATERIALS AND THE INTRASTATE TRANSPORTATION OF AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS IN THE STATE OF COLORADO 8 CCR 1507-25 [Editor’s Notes follow the text of the rules at the end of this CCR Document.] _________________________________________________________________________ AUTHORITY The Chief of the Colorado State Patrol (CSP) is authorized by §42-20-108 (1) and (2) and §§42-20-403, 504, and 508, CRS, to promulgate rules and regulations for the permitting, routing and safe transportation of hazardous and nuclear materials by motor vehicle within the state of Colorado, both in interstate and intrastate transportation. Pursuant to §42-20-108.5, CRS, the Chief of the CSP is authorized to adopt rules and regulations which exempt agricultural products from the hazardous materials rules. APPLICABILITY These rules and regulations shall apply to all persons who transport, ship or cause to be transported or shipped, a hazardous material by motor vehicle over the public roads of this state. COMPLIANCE WITH 8 CCR 1507-1 All commercial vehicles that transport hazardous and/or nuclear materials shall comply with the rules and regulations found at 8 CCR 1507-1, Concerning the Minimum Standards for the Operation of Commercial Vehicles. GENERAL DEFINITIONS Unless otherwise specified, definitions of general applicability throughout these rules are: Enforcement Official: As identified within §42-20-103 (2), CRS, the definition of enforcement official is limited to a peace officer who is an officer of the CSP as described in §§16-2.5-101 and 114, CRS; a certified peace officer who is a certified Port of Entry (POE) officer as described in §§16-2.5-101 and 115, CRS; a peace officer who is an investigating official of the Public Utilities Commission (PUC) transportation section as described in §§16-2.5-101 and 143, CRS; or any peace officer as described in §16-2.5-101, CRS. -

I-25/I-80 Fonsi

Finding of No Significant Impact for the I-25/I-80 Interchange Laramie County, Wyoming WYDOT Project Number I806212 FHWA—WYDOT—EA-20-01 Wyoming Department of Transportation and U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration August 2020 The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) has determined that the Preferred Alternative (which includes full replacement of both the Interstate (I)-25/I-80 and I-25/U.S. Highway 30 (Lincolnway) interchanges, lengthened merge and diverge areas, flyover ramps, auxiliary lanes, braided ramps, widening the curve along eastbound I-80 approaching the interchange, expanding the radius of remaining cloverleaf ramps, and variable message and new static signage) will have no significant impact on the human or natural environment. This Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) is based on the Environmental Assessment for the I-25/I-80 Interchange, Laramie County (FHWA—WYDOT—EA- 20-01) (EA) and subsequent comments received during the public and agency review period, which have been independently evaluated by FHWA. FHWA has determined that the EA adequately and accurately discusses the need, environmental issues, and impacts of the proposed project and appropriate mitigation measures. The EA provides sufficient evidence and analysis for determining that an Environmental Impact Statement is not required. The FHWA takes full responsibility for the accuracy, scope, and content of the EA. Approved by: Bryan Cawley, P.E. Digitally signed by BRYAN R CAWLEY Date: 2020.08.24 12:30:49 -06'00' Division Administrator Date Wyoming Division Federal Highway Administration FINDING OF NO SIGNIFICANT IMPACT Statute of Limitations The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) may publish a notice in the Federal Register, pursuant to 23 United States Code Section 139(l), indicating that one or more federal agencies have taken final action on permits, licenses, or approvals for a transportation project. -

Socioeconomic Assessment for the Tonto National Forest

4. Access and Travel Patterns This section examines historic and current factors affecting access patterns and transportation infrastructure within the four counties surrounding Tonto National Forest (TNF). The information gathered is intended to outline current and future trends in forest access as well as potential barriers to access encountered by various user groups. Primary sources of data on access and travel patterns for the state’s national forests include the Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT), the Arizona Department of Commerce (ADOC), and the circulation elements of individual county comprehensive plans. Indicators used to assess access and travel patterns include existing road networks and planned improvements, trends in vehicle miles traveled (VMT) on major roadways, seasonal traffic flows, and county transportation planning priorities. Additional input on internal access issues has been sought directly from forest planning staff. Various sources of information for the area surrounding TNF cite the difficulty of transportation planning in the region given its vast geographic scale, population growth, pace of development, and constrained transportation funding. In an effort to respond effectively to such challenges, local and regional planning authorities stress the importance of linking transportation planning with preferred land uses. Data show that the area surrounding Tonto National Forest saw relatively large increases in VMT between 1990 and 2000, mirroring the region’s relatively strong population growth over the same period. Information gathered from the Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT) and county comprehensive plans suggest that considerable improvements are currently scheduled for the region’s transportation network, particularly when compared to areas surrounding Arizona’s other national forests. -

Animation Building June 15, 2012

MERCHandise Shopping opportunity JUNE 15, 2012 Anim Ation Building DISNEY CALIFORNIA ADventure® park © Disney/Pixar 3 7-11 12-1 6 ZONE1 commemorative dated collection 1 1 UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE POSTCARD CANCELLATION $3.95 Limit TWO (2) per Guest 2 2 BRONZE MAGNUM COIN Edition Size: 250 Dimensions: 2.5” diameter $75 Limit ONE (1) per Guest 4 3 EmbS OS ED WATCH $89.95 Limit ONE (1) per Guest 4 TumbER L $16.95 Limit TWO (2) per Guest BKAC 5 BA SEBALL CAP 5 $21.95 Limit TWO (2) per Guest FRONT 6 C ANVAS TOTE $34.95 Limit TWO (2) per Guest 6 7-11 L ADIES COMMEMORATIVE TEE $31.95 S (7), M (8), L (9), XL (10), XXL (11) Limit TWO (2) of each size per Guest 12-16 COMMEMORATIVE TEE (ADULT) $27.95 S (12), M (13), L (14), XL (15), XXL (16) Limit TWO (2) of each size per Guest 17 WALT & MICKEY “STORYTELLERS” STATUE Edition Size: 250 Dimensions: 91/4” H x 5” W x 3” D (with base) $195 17 Limit ONE (1) per Guest Paid admission is required to enter Disney Theme Parks. All events and information are subject to cancellation or change without notice including but not limited to dates, times, artwork, release dates, edition sizes and retails sizes. ©Disney/Pixar 1 5 ZONE2 PINS 1 “ I WAS THERE” – DISNEY CALIFORNIA ADVENTURE® PARK Edition size: 5,000 $13.95 Limit ONE (1) per Guest 2 “ I WAS THERE” – CARS LAND Edition Size: 2,000 $13.95 Limit ONE (1) per Guest 2 3 D ISNEY CALIFORNIA ADVENTURE® PARK COMMEMORATIVE Edition Size: 2,500 $13.95 6 Limit ONE (1) per Guest 4 WALT & MICKEY PORTRAIT Edition Size: 1,000 $15.95 Limit ONE (1) per Guest 5 WALT DEDICATION Edition Size: 2,000 $13.95 3 7 Limit ONE (1) per Guest 6 CDARS LAN GRAND OpENING Edition Size: 2,000 $13.95 Limit ONE (1) per Guest 7 R ADIATOR SPRING RACERS GRAND OpENING 8 Edition Size: 2,000 $11.95 Limit ONE (1) per Guest 8 Lu IGI’S FLYING TIRES G RAND OpENING Edition Size: 2,000 $11.95 4 Limit ONE (1) per Guest 9 9 MATER’S JUNKYARD JAMBOREE G RAND OpENING Edition Size: 2,000 $11.95 Limit ONE (1) per Guest Paid admission is required to enter Disney Theme Parks. -

Appendix L: Design Guidelines: I-5 NCC Project

Appendix L: Design Guidelines: I-5 NCC Project Appendix L: Design Guidelines: I-5 NCC Project I-5 North Coast Corridor Project Final EIR/EIS page L-1 Appendix L: Design Guidelines: I-5 NCC Project I-5 North Coast Corridor Project Final EIR/EIS page L-2 Design Guidelines Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project September 2013 Prepared by: Caltrans District 11 | T.Y. Lin International | Safdie Rabines Architects | Estrada Land Planning Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project – Design Guidelines Design Guidelines Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project Prepared by: Caltrans District 11 4050 Taylor Street San Diego, CA 92110 T.Y. Lin International 404 Camino del Rio South, Suite 700 San Diego, CA 92108 | 619.692.1920 Safdie Rabines Architects 925 Ft. Stockton Drive San Diego, CA 92123 | 619.297.6153 Estrada Land Planning 755 Broadway Circle, Suite 300 San Diego, CA 92101 | 619.236.0143 Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project – Design Guidelines Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project – Design Guidelines Table of Contents Design Guidelines Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project Table of Contents I. Project Background D. Design Themes....................17 vi. Typical Freeway Undercrossing. 36 vii. Typical Bridge Details. 37 A. Introduction....................1 i. Corridor Theme Elements. 17 ii. Corridor Theme Priorities. 19 - Southern Bluff Theme....................38 B. Purpose.......................1 - Coastal Mesa Theme.....................39 iii. Corridor Theme Units. 20 C. Components & Products. 1 - Northern Urban Theme. 40 - Southern Bluff Theme....................21 D. The Proposed Project. 2 - Coastal Mesa Theme.....................22 B. Walls.............................41 E. Previous Relevant Documents. 3 - Northern Urban Theme. 23 i. Theme Unit Specific Wall Concepts. -

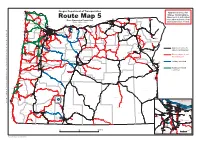

Route Map 5 Ä H339 Æ

ASTORIA Oregon Department of Transportation Warrenton H104 Svensen Approved routes for Mayger 30 Westport ¤£ Clatskanie Æ 101 Olney Ä Rainier ¤£ H105 Triples Combinations. Æ Gearhart C L A T S O PÄ 47 Prescott SEASIDE Goble H332 202 Mist 73300 Movement is authorized 395 Umapine Necanicum Cold ¤£2 Jewell ¤£ Springs Jct. C O L U M B I A Æ Ä MP 9.76 Umatilla Jct. Milton-Freewater Flora Ä Æ Æ Cannon Beach Route Map 5 Ä H339 Æ H103 Pittsburg Irrigon Ä only under authority of an Columbia City Æ Over-Dimension Permit Unit Ä Elsie 47 730 Holdman 53 ST. HELENS ¤£ Helix 11 Vernonia Boardman 0 207 26 7 30 82 Athena Æ ¤£ Ä Over-Dimension Permit. ¤£ Revised March 2020 HERMISTON 3 ¨¦§ H Heppner Jct. Æ Ä H334 Weston Scappoose Stanfield 3 Nehalem 3 Adams 204 Manzanita HOOD Permission not granted to 5 RIVER cross RR crossing at MP 102.40 30 37 Æ 84 30 Echo Ä Wheeler Buxton £ in Hood River 84 ¤£ Arlington H W A L L O W A ¤ 3 Cascade ¨¦§ Biggs § MP 13.22 ¨¦ 26 Locks Jct. Rufus 3 Æ Rockaway Celilo Blalock Ä H320 1 Æ T I L L A M O O K ¤£ Mosier Ä 82 Beach Banks North H281 PENDLETON Plains PORTLAND Æ Ä Minam Imnaha Odell Wallowa Æ Ä 74 Garibaldi Wasco 207 W A S H I N G T O N The Elgin . Bay City Troutdale Multnomah Æ CorneliusÄ Fairview Dalles t Forest HILLSBORO H O O D H282 206 i 6 Grove Falls G I L L I A M Wood 84 Oceanside Beaverton R I V E R U M A T I L L A Summerville m H131 Village Ione r 8 ¨¦§ Lostine Æ Parkdale 197 Ä Gresham Moro 0 e Tillamook M U L T N O M A H MP 83.00 ¤£ 30 Imbler 5 Netarts ENTERPRISE Æ Ä Pilot 3 Æ Ä £ Æ Ä ¤ p Æ Ä Rock H Gaston Tigard -

Last Link of I-90 Ends 30-Year Saga by Peggy Reynolds, Seattle Times, 9 Sept 1993

Last Link Of I-90 Ends 30-Year Saga By Peggy Reynolds, Seattle Times, 9 Sept 1993 Erica Clibborn's red convertible will be one of the first cars Sunday across the new Lacey V. Murrow Floating Bridge, last link in a project that started before Erica was born. The University of Washington junior, who will be going home to Mercer Island for Sunday dinner, was born in 1973, the year a federal court sent the Seattle-area stretch of Interstate 90 back to square one. By then, I-90 already reached most of the 3,063 miles from Boston to south Bellevue, and the final major segment had been in the works for 10 years. It would be another 20 years before that last 7 miles would be finished. That completion will be marked this weekend with an array of public events, and Clibborn and other drivers should be able to go across the eastbound span by 5 p.m. Sunday. That opening means that I-90 survived the anti-government sentiment of the late 1960s, the mass-transit worship of the '70s and the budget cutbacks of the '80s - even while other urban interstate projects were biting the dust in New York, Chicago, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Washington, San Francisco and Portland. Nevertheless, whether or not I-90 was really needed was subject to debate at all levels. It attracted a formidable enemies list, and was rescued regularly by a cast of hundreds. Without any one of its friends in local governments, on the state Transportation Commission, in the Legislature and in Congress, I-90 could have ended in south Bellevue instead of making it to its junction with Interstate 5 in Seattle. -

Florida Traveler's Guide

Florida’s Major Highway Construction Projects: April - June 2018 Interstate 4 24. Charlotte County – Adding lanes and resurfacing from south of N. Jones 46. Martin County – Installing Truck Parking Availability System for the south- 1. I-4 and I-75 interchange -- Hillsborough County – Modifying the eastbound Loop Road to north of US 17 (4.5 miles) bound Rest Area at mile marker 107, three miles south of Martin Highway / and westbound I-4 (Exit 9) ramps onto northbound I-75 into a single entrance 25. Charlotte County – Installing Truck Parking Availability System for the SR 714 (Exit 110), near Palm City; the northbound Rest Area at mile marker point with a long auxiliary lane. (2 miles) northbound and southbound Weigh Stations at mile marker 158 106, four miles south of Martin Highway /SR 714 (Exit 110) near Palm City; the southbound Weigh-in-Motion Station at mile marker 113, one mile south of 2. Polk County -- Reconstructing the State Road 559 (Ex 44) interchange 26. Lee County -- Replacing 13 Dynamic Message Signs from mile marker 117 to mile marker 145 Becker Road (Exit 114), near Palm City; and the northbound Weigh-in-Motion 3. Polk County -- Installing Truck Parking Availability System for the eastbound Station at mile marker 92, four miles south of Bridge Road (Exit 96), near 27. Lee County – Installing Truck Parking Availability System for the northbound and westbound Rest Areas at mile marker 46. Hobe Sound and southbound Rest Areas at mile marker 131 4. Polk County -- Installing a new Fog/Low Visibility Detection System on 47. -

I-90 Tolling Update

I-90 Tolling Update John White Director of Tolled Corridors Development Paula Hammond Steve Reinmuth Secretary of Transportation Chief of Staff Seattle City Council January 28, 2012 I-90 is part of the Cross-Lake Washington Corridor • Represents two major east-west “Cross- Lake” travel corridors: I-90 and SR 520. • WSDOT is tolling SR 520 as part of a multi- faceted financing strategy to help generate enough revenue to fund replacement of the structurally-vulnerable bridge. • A new 520 bridge will give Cross-Lake WA travelers a safer, more reliable trip. 2 Funding for the SR 520 Program Construction Unfunded Program cost estimate (Oct. 2012): $4.13 billion What’s funded: $2.72 billion (includes sales tax deferral) • Pontoon construction in Grays Harbor. • The floating bridge and landings. • Eastside transit and HOV improvements. • The north half of the west approach bridge. Updated November 2012 Costs and Funding for Replacing SR 520 Bridge SR 520 program cost estimate $4.128 B Funding received to date $2.724 B State and local funding (Nickel and TPA) $0.55 B Federal funding $0.12 B SR 520 Account (tolling and future federal funds) $1.91 B Toll proceeds • TIFIA $300M • Triple pledge bonds $550M • First tier toll $159M • PAYGO $74M Federal proceeds • GARVEE $825M Deferred sales tax $0.14 B Unfunded need $1.404 B Program cost estimate based on 2012 CEVP - updated 10/25/12 4 Early Indicators of 520 Toll Success • Meeting or beating traffic forecasts. • Meeting revenue forecasts. • Most people are paying with Good To Go! accounts. – More than 384,000 active Good To Go! accounts. -

Federal Register/Vol. 65, No. 233/Monday, December 4, 2000

Federal Register / Vol. 65, No. 233 / Monday, December 4, 2000 / Notices 75771 2 departures. No more than one slot DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION In notice document 00±29918 exemption time may be selected in any appearing in the issue of Wednesday, hour. In this round each carrier may Federal Aviation Administration November 22, 2000, under select one slot exemption time in each SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION, in the first RTCA Future Flight Data Collection hour without regard to whether a slot is column, in the fifteenth line, the date Committee available in that hour. the FAA will approve or disapprove the application, in whole or part, no later d. In the second and third rounds, Pursuant to section 10(a)(2) of the than should read ``March 15, 2001''. only carriers providing service to small Federal Advisory Committee Act (Pub. hub and nonhub airports may L. 92±463, 5 U.S.C., Appendix 2), notice FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: participate. Each carrier may select up is hereby given for the Future Flight Patrick Vaught, Program Manager, FAA/ to 2 slot exemption times, one arrival Data Collection Committee meeting to Airports District Office, 100 West Cross and one departure in each round. No be held January 11, 2000, starting at 9 Street, Suite B, Jackson, MS 39208± carrier may select more than 4 a.m. This meeting will be held at RTCA, 2307, 601±664±9885. exemption slot times in rounds 2 and 3. 1140 Connecticut Avenue, NW., Suite Issued in Jackson, Mississippi on 1020, Washington, DC, 20036. November 24, 2000. e. Beginning with the fourth round, The agenda will include: (1) Welcome all eligible carriers may participate. -

OCF Disney BG 7375.Indd

DISNEYLAND RESORT EXPANSION questions for Disneyland President George A. Kalogridis 10We caught up with Disneyland Resort President George A. Kalogridis to get some insight into the thought behind this enormous expansion project, as well as some challenges and surprises over the last fi ve years. Here’s what he had to share. 1. Why did Disney make such a large investment to 6. You previously said that one of change Disney California Adventure? the things that had been missing from Disney Since opening in 2001, Disney California Adventure has California Adventure was nighttime entertainment? been the second most-visited theme park in the Western True. The park didn’t have a nighttime spectacular and United States, behind only Disneyland. Though many of World of Color has provided that one last memory as guests the highest-rated attractions are in California Adventure, leave our park. World of Color has entertained more than our guests told us they didn’t have the same emotional 5.5 million guests in just two years, and it has resulted in connection that they had to Disneyland. They wanted more increased park operating hours each evening… along with heart, more fantasy and more immersive experiences. sparking the addition of our nightly family dance parties. 2. How will you connect guests emotionally to Disney 7. What’s the concept behind the family dance parties? California Adventure? We created GlowFest to keep our guests engaged before As guests enter, they will be transported to the 1920s Los and after World of Color shows. We used the concept to Angeles that greeted Walt Disney when he arrived as a create ElecTRONica, a tribute to the movie TRON. -

What Would You Do If You Met a Fairy

Disney•Pixar’s CARS Blu-ray™ Fact Sheet Film Synopsis: From the acclaimed creators of Toy Story, The Incredibles and Finding Nemo comes Disney•Pixar’s Cars, a high-octane adventure comedy that shows life is about the journey, not the finish line. Enjoy this landmark classic on both Disney Blu-ray™ hi-def and DVD in this sensational 2-Disc Blu-ray Combo Pack releasing on April 12, 2011. Hotshot rookie race car Lightning McQueen (Owen Wilson) is living life in the fast lane until he hits a detour on the way to the most important race of his life. Stranded in Radiator Springs, a forgotten town on the old Route 66, he meets Sally (Bonnie Hunt), Mater (Larry The Cable Guy), Doc Hudson (Paul Newman), and a variety of quirky characters who help him discover that there’s more to life than trophies and fame. U.S. Release Date: April 12, 2011 (Direct Prebook: February 15; Distributor Prebook: March 2) Rating: “G” Feature Run Time: Approximately 117-minutes Release Format: Blu-ray Combo Pack (Blu-ray + DVD) Suggested Retail Pricing: 2-Disc Blu-ray Combo Pack = $39.99 U.S. / $44.99 Canada Bonus Features: Carfinder Game Deleted Scenes Mater and the Ghostlight Short Radiators Springs Featurettes One Man Band Short Inspiration for Cars Cine-Explore Voice Talent: Owen Wilson (Wedding Crashers, Little Fockers) as Lightning McQueen; Paul Newman (Road To Perdition, The Sting) as Doc Hudson; Bonnie Hunt (TV’s “The Bonnie Hunt Show,” The Green Mile) as Sally Carrera; Larry the Cable Guy (TV’s “Only in America with Larry the Cable Guy; Larry the Cable Guy: Health Inspection) as Mater; Cheech Marin (The Perfect Game; TV’s “Nash Bridges”) as Ramone; Tony Shalhoub (TV’s “Monk,” “Wings”) as Luigi; George Carlin (Dogma, Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure) as Fillmore; Michael Keaton (The Other Guys, Batman, Toy Story 3) as Chick Hicks; Mario Andretti (Champion Racecar Driver) as himself; Bob Costas (TV Sportscaster) as Bob Cutlass; Dale Earnhardt, Jr.