'Il;Nit 8 Nature of Regional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page-6-Editorial.Qxd

SUNDAY, APRIL 11, 2021 DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU Excelsiordaily Established 1965 Emperor Lalitaditya Muktapida of Kashmir Founder Editor S.D. Rohmetra Autar Mota MARTAND SUN TEMPLE Lalitaditya established many cities and towns . " If I had sent against you the King of King Lalitaditya built the Martand Sun These could be listed as under:- Kashmir on whose royal threshold the other Celebrations at CRPF alitaditya Muktapida (r.c. 724 CE-760 Temple in Kashmir on the plateau near Mattan 1. Sunishchita-pura. rulers of Hind had placed their heads, who sways CE) was a powerful Kayastha ruler of the town in South Kashmir. The location of the tem- 2. Darpita-pura. the whole of Hind, even the countries of Makran LKarkota dynasty of Kashmir . Kalhana , ple proves the skill and expertise of Kashmiri 3. Phala-pura. and Turan, whose chains a great many noblemen commando's house the 12th century chronicler ,calls him universal artisans of the period. It is said that from this M. A. Stein has identified this place with near and grandees have willingly placed on their monarch or the conqueror of the world, crediting on of the soil and a courageous CoBRA com- temple, one could see the entire Lidder valley present-day Shadipura town in Kashmir. knees." him with far-reaching conquests from Central and the Shikhara of the demolished 4. Parnotsa. The king of Kashmir referred to here is none mando of the CRPF, constable Rakeshwar Asia to shores of Arbian sea in India. According Vijeyshawara Shrine near the present-day M. A. Stein has identified this place as pres- other than Lalitaditya. -

Traditional Knowledge Systems and the Conservation and Management of Asia’S Heritage Rice Field in Bali, Indonesia by Monicavolpin (CC0)/Pixabay

ICCROM-CHA 3 Conservation Forum Series conservation and management of Asia’s heritage conservation and management of Asia’s Traditional Knowledge Systems and the Systems Knowledge Traditional ICCROM-CHA Conservation Forum Series Forum Conservation ICCROM-CHA Traditional Knowledge Systems and the conservation and management of Asia’s heritage Traditional Knowledge Systems and the conservation and management of Asia’s heritage Rice field in Bali, Indonesia by MonicaVolpin (CC0)/Pixabay. Traditional Knowledge Systems and the conservation and management of Asia’s heritage Edited by Gamini Wijesuriya and Sarah Court Forum on the applicability and adaptability of Traditional Knowledge Systems in the conservation and management of heritage in Asia 14–16 December 2015, Thailand Forum managers Dr Gamini Wijesuriya, Sites Unit, ICCROM Dr Sujeong Lee, Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA), Republic of Korea Forum advisors Dr Stefano De Caro, Former Director-General, ICCROM Prof Rha Sun-hwa, Administrator, Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA), Republic of Korea Mr M.R. Rujaya Abhakorn, Centre Director, SEAMEO SPAFA Regional Centre for Archaeology and Fine Arts Mr Joseph King, Unit Director, Sites Unit, ICCROM Kim Yeon Soo, Director International Cooperation Division, Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA), Republic of Korea Traditional Knowledge Systems and the conservation and management of Asia’s heritage Edited by Gamini Wijesuriya and Sarah Court ISBN 978-92-9077-286-6 © 2020 ICCROM International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property Via di San Michele, 13 00153 Rome, Italy www.iccrom.org This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution Share Alike 3.0 IGO (CCBY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo). -

Jhajjar Through Ages

1 1 Jhajjar Through Ages *Dr. Jagdish Rahar Abstract Jhajjar is 35 KMs. to the south of Rohtak and 55 KMs. west of Delhi. The name of district is said to be derived from its supported founder, One Chhaju and Chhaju Nagar converted into Jhajjar. Another derivation connects the name with a natural fountain called Jhar Nagar. A third derivation is from Jhajjar, a water vessel, because the surface drainage of the country for miles runs into the town as into a sense. Introduction : Unfortunately, the archeologists have paid little attention to the region of the present study, therefore, the detailed information ancient people of Jhajjar (Haryana) region is not known. However, now an attempt has been made to throw welcome light on the ancient cultures of Jhajjar on the basis of information collected from explorations and as well as from the excavations conducted in the different parts of Haryana. Seed of Colonization: Pre-Harappan : The archeological discoveries proved beyond doubt that the region under present study was inhabited for the first time in the middle of the third millennium B.C. by a food producing farming and pastoral community known as ‘Pre-Harappan’. During the course of village to village survey of this region, six sites were discovered by the researcher which speaks of Pre- Harappan culture namely Mahrana, Kemalgarh, SilaniKesho, Raipur, Silana II, Surha.1 All these sites have cultural identity with Kalibangan-I1, Siswal2, Banwali3, Mitathal-I4 and Balu-A5, where Pre-Harappan peoples in the middle of the third millennium B.C. mode their settlements.. Terracotta bangles were also used as the ornaments. -

Ancient History Notes

History – : is a record of people, places and events of the past, Lothal – Ghaggar – Kathiyawar (GJ) arranged in chronological order. Their lifestyles, occupations, Kalibanga – Ghaggar – Ganganagar (RJ) customs etc. Banwali – Saraswati – Hissar (HR) Pre – history – : the period of before writing was invented. It is Dholavira – Luni – Kutch (GJ) studied & reconstructed with the help of archaeological remains such as bones, coins, tools jewellery, ruins of building etc. Area – 13 lakhs sq. km app. Cuneiform was the world’s first written language by the Sumerians Shape – triangular created it over 5000 years ago, into a slab of wet clay and then baked 1920 – excavation of IVC took place under Sir John Marshall. It is hard in a kiln. spread over Punjab, Haryana, Sindh, Baluchistan, Rajasthan, Guj. & The early writing was on rocks, stone walls, pillars, clay. fringes of western UP. Sources of history 1921 Harappa (Modern site) was discovered in the province of a) monuments & objects – old buildings, tools, weapons, pottery, western Punjab on the bank of river Ravi by Dayaram Sahni. In statues, ornaments, seals toys paintings etc. Montgomri dist. of Pakistan. b) coins – which display their empires, economics conditions, trade 1922 Mohen Jo Daro was excavated by R.D. Banerjee on the bank of art & religion of that era. river Indus. In Larkan district of Pakistan. c) inscriptions – written during the reign of great kings and are still Lothal (GJ) – dockyard, Harappa – graveyard intact in their original form. (R – 37), Mohan jo Daro – big granary store, bronze dancing girl (23 Literary sources – handwritten records of the past known as cm), statue of priest & shiva, swimming pool (39x23x8) ft. -

Lalitaditya, the Alexander of India B

Lalitaditya, The Alexander of India B. L. Razdan e was the ever undefeated king who blasted the myth that King of Kashmir who tasted Indians were never able to capture Hvictory everywhere he went. any foreign lands. Chinese, the Turkish and the Tibetan This great son of India who legends referred to him as a great hailed from Kashmir was none conqueror. He was the first Indian other than Lalitaditya Muktapida of king who gave a befitting reply to Karkota dynasty, the mightiest the invading Arabs; one of the few Indian king of his times and beyond. Indian kings who was able to Believed to be the youngest of the capture Central Asia. A Kashmiri three sons of Kashmiri king king, his influence spread even to Durlabhaka (alias Pratapaditya), South India and played an Lalitaditya ascended the throne in important role in the foundation of 724 AD at a time when the Karkota the Rashtrakuta empire there, dynasty ruled over the present day which became one of the most Jammu & Kashmir, Punjab and powerful kingdoms to have ever Haryana. Lalitaditya not only existed in South India. He was the stopped the Arabs from entering Bhavan’s Journal, 31 May, 2020 u 63 India but also conquered parts of around 7th century A.D. Lalitadatiya Iran and extended his kingdom having found a natural ally in China, upto Tibet and China. His made a smart diplomatic move by successful efforts to protect aligning with the latter and took Kashmir and India is something advantage of the advanced Chinese which the Indian nation cannot military technologies that helped and should never forget. -

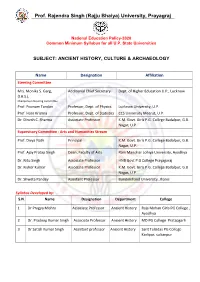

Prof. Rajendra Singh (Rajju Bhaiya) University, Prayagraj

Prof. Rajendra Singh (Rajju Bhaiya) University, Prayagraj National Education Policy-2020 Common Minimum Syllabus for all U.P. State Universities SUBJECT: ANCIENT HISTORY, CULTURE & ARCHAEOLOGY Name Designation Affiliation Steering Committee Mrs. Monika S. Garg, Additional Chief Secretary Dept. of Higher Education U.P., Lucknow (I.A.S.), Chairperson Steering Committee Prof. Poonam Tandan Professor, Dept. of Physics Lucknow University, U.P. Prof. Hare Krishna Professor, Dept. of Statistics CCS University Meerut, U.P. Dr. Dinesh C. Sharma Associate Professor K.M. Govt. Girls P.G. College Badalpur, G.B. Nagar, U.P. Supervisory Committee - Arts and Humanities Stream Prof. Divya Nath Principal K.M. Govt. Girls P.G. College Badalpur, G.B. Nagar, U.P. Prof. Ajay Pratap Singh Dean, Faculty of Arts Ram Manohar Lohiya University, Ayodhya Dr. Nitu Singh Associate Professor HNB Govt P.G College Prayagaraj Dr. Kishor Kumar Associate Professor K.M. Govt. Girls P.G. College Badalpur, G.B. Nagar, U.P. Dr. Shweta Pandey Assistant Professor Bundelkhand University, Jhansi Syllabus Developed by: S.N. Name Designation Department College 1 Dr Pragya Mishra Associate Professor Ancient History Raja Mohan Girls PG College , Ayodhya 2 Dr. Pradeep Kumar Singh Associate Professor Ancient History MD PG College Pratapgarh 3 Dr Satish Kumar Singh Assistant professor Ancient History Sant Tulsidas PG College Kadipur, sultanpur Prof. Rajendra Singh (Rajju Bhaiya) University, Prayagraj Semester-wise Titles of the Papers Year Sem. Course Course Title Theory/ Maximum Maximum -

PRE-Mix December 2020

PRE-Mix (Compilations of the Multiple Choice Questions) For the Month Of December 2020 Visit our website www.sleepyclasses.com or our YouTube channel for entire GS Course FREE of cost Also Available: Prelims Crash Course || Prelims Test Series T.me/SleepyClasses Table of Contents 1. Geography ...........................................................................................................1 2. History & Culture .............................................................................................19 3. Polity & Governance .......................................................................................37 4. Economy ..............................................................................................................56 5. Environment & Ecology .................................................................................75 6. Science & Technology .....................................................................................93 www.sleepyclasses.com Call 6280133177 T.me/SleepyClasses 1. Geography Click on the links given below to watch the following questions on YouTube • Video 1 • Video 2 • Video 3 • Video 4 1. Shahtoot dam, recently heard in news, is in A. Pakistan B. Afghanistan C. India D. Bhutan Answer: B Explanation • India will be constructing the Shahtoot Dam on Kabul River in Afghanistan and that the Governments of two nations have recently concluded an agreement for the same. • The dam's construction would provide safe drinking water to two million residents of Kabul city which is the Afghan -

The Maukharis of Kanauj

AJMR Asian Journal of Multidimensional Research A Publication of TRANS Asian Research Journals Vol.2 Issue 6, June 2013, ISSN 2278-4853 THE MAUKHARIS OF KANAUJ Dr. Moirangthem Pramod* *Assistant Professor, G. G. D. S. D. College, Chandigarh, India. INTRODUCTION With the coming of kumāragupta III on the throne of Magadha, the weakness of the imperial Gupta had become a known fact to all. Taking advantage of the situation some feudatories of the Guptas raised their heads to grab the political power in north India to establish their own independent kingdoms. Among these feudatories, the Maukharies of kanauj was one of them. This branch of the Maukharis is known from the seals and inscriptions discovered from the modern districts of Farrukhabad, Gorakhpur, Jaunpur and Barabanki of Uttar Pradesh, Patna district of Bihar, Nimad district of Madhya Pradesh and from the literary work like Bāṇa‟s Harshacharita. As most of the seals and inscriptions of this Maukhari family are discovered from the above mentioned district of Uttar Pradesh, their seat of power should be roughly placed in this part of the state. Even though, we do not have any hard facts about the capital of this ruling family, it is generally agreed that Kanauj (ancient Kānyakubja) must have been the center of their rule.1 Harivarman is described as the progenitor of the Kanauj branch of Maukharis. In the inscriptions and seals which we have discovered till now, he is given the simple title, Mahārāja indicative of his feudatory position. It is very likely that he was the contemporary of Kṛishṇagupta, the founder of the Later Gupta dynasty. -

The Early Ristory of the H Uns and Their Inroads in India and Persia

The Early Ristory of the H uns and Their Inroads in India and Persia. (Read on 28th August 1916.) I. During the present war, we have been often hearing of the a ncient Huns, because some of the ways of fighting of our Introduction. enemies have been compared to those of these people. Again, the German Emperor himself had once referred to them in his speech before his troops when he sent them under the command of his brother to China to fight ;tgainst the Boxers. H e had tlius addressed them :-" When you meet the foe you.will defeat him. No quarter will be given, no prisoners will be taken. Let all who fall into your ha nds be at your mercy. Just as Huns, a thousand years ago, under the leadership of Attila, gained a reputation in virtue of which they still live in historic tradition, so may the na me of Germany become known in such a manner in China that no Chinama n will ever again da re even to look askance at a German." Well-nigh all the countries, where war is being waged at present, were, at one time or another, the fields of the war-like activities of the Huns . Not only that, but the history of almost all the nations, engag .ed in the present war, have, at one time or another, been affected by the hi story of the Huns. The early ancestors of almost all of them had fought with the Huns. The writer of the article on Huns in the Encyclopredia Brita nnica 1 says, that " the authentic history of the Huns in When does the Europe practically begins about the year 372 History of the Huns A.D., when under a leader named Balamir (or .begin ? Ba la mber) they began a westward movement from their setUements in the steppes lying to the north of the Caspian." Thoug h their strictly a uthentic history may be said to begin with the Christian era, or two or three centuries later, their semi-authentic history began a very long time before that. -

J825js4q5pzdkp7v9hmygd2f801.Pdf

INDEX S. NO. CHAPTER PAGE NO. 1. ANCIENT INDIA - 1 a. STONE AGE b. I. V. C c. PRE MAURYA d. MAURYAS e. POST MAURYAN PERIOD f. GUPTA AGE g. GUPTA AGE h. CHRONOLOGY OF INDIAN HISTORY 2. MEDIVAL INDIA - 62 a. EARLY MEDIEVAL INDIA MAJOR DYNASTIES b. DELHI SULTANATE c. VIJAYANAGAR AND BANMAHI d. BHAKTI MOVEMENT e. SUFI MOVEMENT f. THE MUGHALS g. MARATHAS 3. MODERN INDIA - 191 a. FAIR CHRONOLOGY b. FAIR 1857 c. FAIR FOUNDATION OF I.N.C. d. FAIR MODERATE e. FAIR EXTREMISTS f. FAIR PARTITION BENGAL g. FAIR SURAT SPLIT h. FAIR HOME RULE LEAGUES i. FAIR KHILAFAT j. FAIR N.C.M k. FAIR SIMON COMMISSION l. FAIR NEHRU REPORT m. FAIR JINNAH 14 POINT n. FAIR C.D.M o. FAIR R.T.C. p. FAIR AUGUST OFFER q. FAIR CRIPPS MISSION r. FAIR Q.I.M. s. FAIR I.N.A. t. FAIR RIN REVOLT u. FAIR CABINET MISSION v. MOUNTBATTEN PLAN w. FAIR GOVERNOR GENERALS La Excellence IAS Ancient India THE STONE AGE The age when the prehistoric man began to use stones for utilitarian purpose is termed as the Stone Age. The Stone Age is divided into three broad divisions-Paleolithic Age or the Old Stone Age (from unknown till 8000 BC), Mesolithic Age or the Middle Stone Age (8000 BC-4000 BC) and the Neolithic Age or the New Stone Age (4000 BC-2500 BC). The famous Bhimbetka caves near Bhopal belong to the Stone Age and are famous for their cave paintings. The art of the prehistoric man can be seen in all its glory with the depiction of wild animals, hunting scenes, ritual scenes and scenes from day-to-day life of the period. -

Vakataka Inscriptions

STRUCTURE OF THE GUPTA AND VAKATAKA POLITY: AN EPIGRAPHICAL STUDY ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OP / JBottor of ^l)iIo!Sopl)p HISTORY BY MEENAKSHI SHARMA Under the Supervision of Prof. B.L. BHADANI (Chairman & Coordinator) CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AUGARH MUSUM UNIVERSITY AUGARH (INDIA) 18 May 2010 ABSTRACT In the present thesis an attempt has been made to give an updated comprehensive study of the polity under the Gupta and the Vakataka empires on the basis of epigraphical material of this period. The general plan of treatment which h^s been followed in this work is as under: * > . Chapter-I deals with the extent .'of the" Gupta empire and its geographical and political conditions under different Gupta kirigs. It describes the political atmosphere which led to the rise and foundation of the Gupta kingdom which later on developed into an empire of great magnitude. While making a precise and concise account of the conquests of Gupta rulers, this chapter focuses at the political agendas and strategies applied by them in order to extend the empire. It is shown that Gupta empire in its glorious days included not only considerable territories of the western and northern India and eastern parts of south India but also colonies in the Far East. The empire was largely constituted by states ruled by different subordinate rulers also called feudatories, important among them were the Valkhas, the Maukharies, the later Guptas, the Parivrajakas, the Uchchakalpas, the Aulikaras and the Maitrakas. These feudatories contributed in the disintegration of the Gupta empire. -

Department of Ancient Indian History and Archaeology, University of Lucknow, Lucknow

Department of Ancient Indian History and Archaeology, University of Lucknow, Lucknow B.A. Semester- I Paper I : Political History of Ancient India (from C 600 B.C. to C 187 B.C.) Unit I 1. Literary and Archaeological sources of Ancient Indian history. 2. Foreign accounts a s a source of Ancient Indian history 3. Political condition of northern India in sixth century BC-Sixteen Mahajanpadas and ten republican states. 4. Administrative system of republican states of sixth century BC 5. Achaemenian invasion of India. Unit II 1. Rise of Madadha-Bimbisara, Afatasatur and the Saisunaga dynasty. 2. Alexander’s invasion of India and its impact. 3. The Nanda dynasty-origin, Mahapadmananda. 4. Causes of downfall of Nanda dynasty. 5. The Mauryan dynasty- sources of study and origin of the Mauryas. Unit III 1. Chandragupta 2. Bindusara 3. Asoka- conquests and extent of empire 4. Policy of dhamma of Asoka 5. Foreign policy of Asoka Unit IV 1. Estimate of Asoka 2. Successors of Asoka 3. Mauryan administration 4. Decline and downfall of the Mauryan dynasty. Suggested readings: 1.Barua, B.M.-Asoka and His Times 2.Bhandarkar, D.R.-Asoka 3.Chattopadhyaya, S- Bimbisara to Asoka-The Rule of the Achaeminids in India. 4.Dikshitar, V.R.R.-The Mauryan Polity. 5.Mookerji, R.K.-Asoka -Hindu Civilisation -Chandragupta Maurya and his Times. 6.Pandey, R.B.-Prachin Bharat. 7.Pandey, V.C.-A New History of Ancient India. 8.Raychaudhuri, H.C.- Political History of Ancient India 9.Sastri K.A.N.- A Comprehensive History of India. - The Age of the Nandas and the Mauryas.