Makingmyownichigenkin.Pdf (1.357Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of California Santa Cruz the Vietnamese Đàn

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ THE VIETNAMESE ĐÀN BẦU: A CULTURAL HISTORY OF AN INSTRUMENT IN DIASPORA A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in MUSIC by LISA BEEBE June 2017 The dissertation of Lisa Beebe is approved: _________________________________________________ Professor Tanya Merchant, Chair _________________________________________________ Professor Dard Neuman _________________________________________________ Jason Gibbs, PhD _____________________________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................................................. v Chapter One. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Geography: Vietnam ............................................................................................................................. 6 Historical and Political Context .................................................................................................... 10 Literature Review .............................................................................................................................. 17 Vietnamese Scholarship .............................................................................................................. 17 English Language Literature on Vietnamese Music -

Freebern, Charles L., 1934

THE MUSIC OF INDIA, CHINA, JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Freebern, Charles L., 1934- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 06:04:40 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290233 This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-6670 FREEBERN, Charles L., 1934- IHE MUSIC OF INDIA, CHINA/JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS. [Appendix "Pronounciation Tape Recording" available for consultation at University of Arizona Library]. University of Arizona, A. Mus.D., 1969 Music University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan CHARLES L. FREEBERN 1970 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED • a • 111 THE MUSIC OP INDIA, CHINA, JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS by Charles L. Freebern A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 9 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA. GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Charles L, Freebern entitled THE MUSIC OF INDIA, CHINA, JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts &• 7?)• as. in? Dissertation Director fca^e After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Connnittee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:" _ ^O^tLUA ^ AtrK. -

UNIVERSITY of HAWAUN'wtytwln ~A~~7,0 CATALOG Z LIBRARY

• v, 44 /YlO.J- UNIVERSITY OF HAWAUN'WtYtWlN ~A~~7,0 CATALOG z LIBRARY en a: w Forty-fourth Annual SUMMER SESSION 1970 Catalog of Courses r • UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII BULLETIN VOL XLIX, NUMBER 2, MARCH 1970 The University of Hawaii Bulletin is pUblished in December, March, and twice in June by the University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S.A. Entered as second-class matter at the post office at Honolulu, Hawaii, November 14, 1921, under Act of Congress of August 24, 1912. PRICE 25 CENTS PLUS POSTAGE \ 1970 SUMMER CALENDAR JUNE SM T W T F S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 JULy SMT W TF S .. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 AUGUST S M T W T F S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 2 SEPTEMBER SMTW T F S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 FIRST TERM ~JUNE IS-JULY 24. ~ June 10, 12, Wednesday, Friday .. Registration for UH students \.-.. and residents of Hawaii June IS, Monday _. -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

Traditional Japanese Musical Instruments 1 Traditional Japanese Musical Instruments

Traditional Japanese musical instruments 1 Traditional Japanese musical instruments Traditional Japanese musical instruments comprise a wide range of string, wind, and percussion instruments. String Plucked • Biwa (琵琶) - pear-shaped lute • Ichigenkin (kanji: 一絃琴) - one-string zither • Koto (琴, 箏) - long zither • Junanagen (十七絃) - 17-stringed zither • Taishogoto (大正琴) - zither with metal strings and keys • Kugo (箜篌) - an angled harp used in ancient times and recently revived • Sanshin (三線) - three-string banjo from Okinawa • Shamisen (三味線) - A banjo-like lute with three strings, the shamisen was brought to Japan from China in the 16th century. Popular in Edo's pleasure districts, the shamisen was often used in Kabuki theater. Made from red sandalwood and ranging from 1.1 to 1.4 meters long, the Kitagawa Utamaro, "Flowers of Edo: Young Woman's shamisen has ivory pegs, strings made from twisted silk, Narrative Chanting to the Shamisen", ca. 1880 and a belly covered in cat or dog skin. The strings, which are of different thickness, are plucked or struck with a tortoise shell pick. • Yamatogoto (大和琴) - ancient long zither; also called wagon (和琴) • Tonkori (トンコリ) - plucked instrument used by the Ainu of Hokkaidō Bowed - bowed lute with three (or, more rarely, four) strings and a skin-covered body Wind Flutes Japanese flutes are called Fue. there are eight different flutes • Hocchiku (法竹) - vertical bamboo flute • Nohkan (能管) - transverse bamboo flute used for noh theater • Ryūteki (龍笛) - transverse bamboo flute used for gagaku • Kagurabue (神楽笛) -

IDEN=ERS Asia

b0C1' 1EIPi REsU ED 11; 241 !_;0 009 AUTHOE H twkin,,John N. 1-0:1ource Handbo kfo Ti Htudie! A off Curr oulum nt irSi1Jr P-sohool through Grade Twelve. IN3TITOTION CailiEornia Univ., Los Anqoles. Committeeot Compatativ and I flt mu tional St udie Prii DATE 76 NOTE 194p. AlimiA 31-E FRom c,Arriculum ceT1t, ncjoi 2(.,Hall Hilgatd AvcAtiq, Cd1 forniz 90024 papcidcic; P72,1PM HC NoL Availabl ft DEJC Anotated Bib_ ographies; *Area Studies; Studies; Bibliographies; Books; *Cros Ci1ltl1Ll Studies; Cultural Differences; CurriculumE aluatioll; Elementary Secondary Education; Yilms; iniTtrp f5Z Foreign Culture; *Instructional Materials; International Studies; Maps; Me surementIns ill,n Periodicals; Phonograph Records; *Resource Slides; Social Studies; Tape Recordings; Transparencies IDEN=ERS Asia AB TPACT This handbook is an annotated bibliogr41 of 1,586 instruct oval riiaterials for teaching about Asia. Existig materials are identified that can be used by precollegiate teachers of all subject areas. The handbook is arranged by grade levelspreschoolto grade 3, grades 4-6, junior high, senior high,and ungraded. Withi each section, materials are divided by geographicregion and listed alphabetically according to their instructionalformats. "The region divisions include East Asia, South Asia, SoutheastAsia, and Pacific Islands. Types of materials include multimedia, books, films, filmstrips, slides, maps and transparencies, records andtapes, aad posters and study prints. Bibliographies,miscellaneous resources, and selected journals are litc,.(1 separately. Entries contain title, date, description, price, and publisher. Some annotationsprovide an evaluation of the material's cross-cultural instructionalvalue- A list of publishers and distributors is included forordering materials. The handbook concludes with two model evaluationforms vhich nay assist teachers in selecting materialson tile basis their cross-cultural value and forpurposes of general assesment. -

Library of Congress Medium of Performance Terms for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue anzhad USE clarinet BT double reed instrument USE imzad a-jaeng alghōzā Appalachian dulcimer USE ajaeng USE algōjā UF American dulcimer accordeon alg̲hozah Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE accordion USE algōjā dulcimer, American accordion algōjā dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, dulcimer, Kentucky garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. dulcimer, lap piano accordion UF alghōzā dulcimer, mountain BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah dulcimer, plucked NT button-key accordion algōzā Kentucky dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn mountain dulcimer accordion band do nally lap dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi plucked dulcimer with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī BT plucked string instrument UF accordion orchestra ngoze zither BT instrumental ensemble pāvā Appalachian mountain dulcimer accordion orchestra pāwā USE Appalachian dulcimer USE accordion band satāra arame, viola da acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute USE viola d'arame UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā arará folk bass guitar USE algōjā A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT guitar alpenhorn BT drum acoustic guitar USE alphorn arched-top guitar USE guitar alphorn USE guitar acoustic guitar, electric UF alpenhorn archicembalo USE electric guitar alpine horn USE arcicembalo actor BT natural horn archiluth An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE archlute required for the performance of a musical USE alphorn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic archiphone form. alto (singer) A microtonal electronic organ first built in 1970 in the Netherlands. BT performer USE alto voice adufo alto clarinet BT electronic organ An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE tambourine archlute associated with Western art music and is normally An extended-neck lute with two peg boxes that aenas pitched in E♭. -

ĐÀN BẦU – TRADITIONAL VIETNAMESE INSTRUMENT (Monochord)

ĐÀN BẦU – TRADITIONAL VIETNAMESE INSTRUMENT (Monochord) Ngo Tra My – Ta Quang Dong 1. An overview of the history and cultural background of the Đàn Bầu Đàn Bầu is a typical musical instrument in the system of Vietnamese traditional instruments. It is also considered one of the most unique instruments in the world because of its simple structure, special performing style and sound produced from the harmonics of the string combined with the use of the rod/handle to tense or loosen the intrument’s single string, creating different pitches with attractive and unique timbre that is close to the tone of Vietnamese laguage. There have been no research documents identifying the exact time of the appearance of the Đàn Bầu. According to some historical records, the Đàn Bầu has been present in Viet Nam since at least 1770. In the book "Đại Nam Thực Lục Tiền Biên" (Annals of Dai Nam – Prequel record), written in 1770, there is a passage that states: "Duc [a Vietnamense scholar who lived in XVIII century. -- Ed.] is good at studying and poetry and super at numerology and music. Legend has it that the Nam cam instrument (also known as the Đàn Bầu) is invented by Duc ... ". In the “Kiến Văn Tiểu Lục ” wrtitten in 1777 by Le Quy Don, there is a passage that states “At the parties of Tap Hien palace, men often play as kép (actor) while women play as đào (actress). They are sitting on the both side of the ground with 10 people each. There are also many kinds of instrument such as the Tỳ Bà (pear-shaped lute), the Tranh (zither), the Đàn Bầu”. -

Arbeitshilfe AH-001 "Liste Der Normierten Besetzungsangaben"

Arbeitsstelle für Standardisierung (AfS) Stand: 13. Oktober 2020 Arbeitshilfe Liste der normierten Besetzungsangaben Besetzung als Element nach RDA 6.15 Besetzung als Ergänzung für Sucheinstiege nach RDA 6.28 Besetzung als Teil des bevorzugten Titels für Werke für eine allgemeine oder eine bestimmte Besetzung nach RDA 6.14.2.8.2 Einleitung Die vorliegende Liste enthält die für D-A-CH normierten Begriffe für die Besetzung nach RDA 6.15 und die Verwendung für den normierten Sucheinstieg nach RDA 6.28. Die Spalten der Tabelle enthalten: A. Besetzung nach Informationsquelle B. Besetzungsangabe nach RDA 6.15 C. Verwendung im normierten Sucheinstieg nach RDA 6.28 D. Verwendungshinweise und Erläuterungen Arbeitshilfe AH-001 1 | 28 Allgemeine Verwendungshinweise Die Liste der Besetzungsangaben kann niemals vollständig sein. Als Besetzung im normierten Sucheinstieg und als Datenelement nach RDA 6.15 können daher auch Instrumente erfasst werden, z. B. seltene Volksmusikin- strumente, die nicht auf der Liste stehen, soweit sie nicht dem Sinn der Liste widersprechen. Wenn sich ein bestimmtes Instrument nicht auf der Liste befindet, bedeutet das also nicht, dass stattdessen ein unbestimmtes Instrument erfasst werden müsste. Die Schreibweise der Instrumente und Besetzungsangaben soll sich an der Dudenschreibweise orientieren. Das ist in der vorliegenden Liste noch nicht voll- ständig vollzogen. Die Besetzung als Ergänzung im Sucheinstieg weicht nur insoweit von der Besetzung nach RDA 6.15 ab, als Ausnahmen gemäß RDA 6.28 zutreffen. Die Spalte C berücksichtigt somit die einzige D-A-CH-relevante Ausnahme RDA 6.28.1.9.1 g) für den normierten Sucheinstieg, nach der bei Instrumenten die Bezeichnung der Tonart oder die Stimmlage wegzulassen sind. -

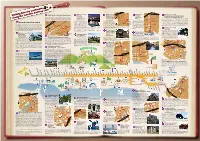

Hanshinensen Map 英語 2

Nishinomiya Sta. Seidou Elementary School 【Mikage Station】 【Ashiya Station】 Ashiya Sta. 【Nishinomiya 【Amagasaki Station】 21 【Daikai Station】Nofuku Temple (Hyogo Daibutsu) 17 11 Ashiya 6 1 Visiting Literary Landmarks Mt. Rokko Tanizaki Junichiro National Route 43 Station】 Nishinomiya Amagasaki Chuo Shopping Arcade & Nofuku Temple is depicted in The Tale of the Heike※, a literary classic. City Hall Shrine Tel:078-894-2210 Ashiya River It is also well known as a temple where Taira no Kiyomori shaved Memorial Museum of Nishinomiya Sanwa Hondori Shopping Arcade along the Hanshin Railway Line National Route 43 There are about 600 stores lining this extensive network of his head and entered the priesthood. The temple houses Hyogo Rokko Cable Car Literature, Ashiya Ashiya City Marina Library Opened in 1945, the marina Hamawaki old classic shopping arcades covering the area stretching Daibutsu, one of Japan's three traditional Great Buddhas in Japan. Tel:078-861-5288 Tel:0797-23-5852 Ashiya Park Junior High Hamawaki The night view of Kobe is one Opened in 1988, the has long been known as a School Elementary School from Amagasaki Station to Deyashiki Station, with a Tanizaki combined length of 2 km. It is said that a shopping arcade in 【Sumaura-Koen Station】Sumaura Park Mizuki of the three greatest night museum houses and Ashiya City Junichiro center of marine sports in 26 Museum of Art an animated cartoon version of The Melancholy of Haruhi Elementary Daikai Sta. views in Japan, along with exhibits various valuable Memorial the Kansai region. It is said The park is famous as a place where the Battle of School and History Museum of Nishinomiya Kofu Yogai Suzumiya was modeled after these arcades, which have those of Hakodate and items related to that a yacht harbor depicted Kindergarten Ichi-no-Tani, one of the fiercest battles of the Genpei War, Literature, High School Nagasaki. -

World of Sound Catalog #2

WORLD OF SOUND CATALOG #2 ORGANIZED IN ORDER BASED ON RECORD LABEL Smithsonian Folkways Recordings ◊ Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology (A.R.C.E.) ◊ Collector Records ◊ Consignment ◊ Cook Records ◊ Dyer-Bennet Records ◊ Fast Folk Musical Magazine ◊ Folkways Records ◊ International Library of African Music (I.L.A.M.) ◊ Monitor Records ◊ Minority Owned Record Enterprises (M.O.R.E.) ◊ Paredon Records ◊ Smithsonian Folkways Special Series *Note – CD price is included here but other formats may also be available including Downloads, Cassette and Vinyl. Published 3/2/2011 Smithsonian Folkways Recordings CATALOG NO. ALBUM TITLE ALBUM ARTIST YEAR CD PRICE* SFW40000 Folkways: The Original Vision Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly 2005 $15.00 SFW40002 Musics of the Soviet Union Various Artists 1989 $15.00 SFW40003 Happy Woman Blues Lucinda Williams 1990 $15.00 SFW40004 Country Songs, Old and New The Country Gentlemen 1990 $15.00 SFW40005 Jean Ritchie and Doc Watson at Folk City Jean Ritchie and Doc Watson 1990 $15.00 SFW40006 Cajun Social Music Various Artists 1990 $15.00 SFW40007 Woody Guthrie Sings Folk Songs Woody Guthrie 1989 $15.00 SFW40008 Broadside Tapes 1 Phil Ochs 1989 $15.00 SFW40009 Freight Train and Other North Carolina Folk Songs and Tunes Elizabeth Cotten 1989 $15.00 SFW40010 Lead Belly Sings Folk Songs Lead Belly 1989 $15.00 Sonny Terry and Brownie SFW40011 Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry Sing 1990 $15.00 McGhee SFW40012 The Doc Watson Family The Doc Watson Family 1990 $15.00 SFW40013 Family Songs and Stories from the North -

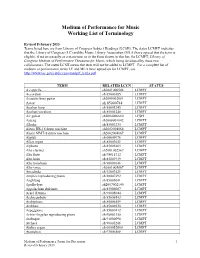

Medium of Performance for Music: Working List of Terminology

Medium of Performance for Music Working List of Terminology Revised February 2013 Terms listed here are from Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH). The status LCMPT indicates that the Library of Congress (LC) and the Music Library Association (MLA) have agreed that the term is eligible, if not necessarily as a main term or in the form shown in this list, for LCMPT, Library of Congress Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music, which being developed by these two collaborators. The status LCSH means the term will not be added to LCMPT. For a complete list of medium of performance terms LC and MLA have agreed on for LCMPT, see http://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/medprf_lcmla.pdf.