Desecheo National Wildlife Refuge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two New Scorpions from the Puerto Rican Island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae)

Two new scorpions from the Puerto Rican island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae) Rolando Teruel, Mel J. Rivera & Carlos J. Santos September 2015 — No. 208 Euscorpius Occasional Publications in Scorpiology EDITOR: Victor Fet, Marshall University, ‘[email protected]’ ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Michael E. Soleglad, ‘[email protected]’ Euscorpius is the first research publication completely devoted to scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones). Euscorpius takes advantage of the rapidly evolving medium of quick online publication, at the same time maintaining high research standards for the burgeoning field of scorpion science (scorpiology). Euscorpius is an expedient and viable medium for the publication of serious papers in scorpiology, including (but not limited to): systematics, evolution, ecology, biogeography, and general biology of scorpions. Review papers, descriptions of new taxa, faunistic surveys, lists of museum collections, and book reviews are welcome. Derivatio Nominis The name Euscorpius Thorell, 1876 refers to the most common genus of scorpions in the Mediterranean region and southern Europe (family Euscorpiidae). Euscorpius is located at: http://www.science.marshall.edu/fet/Euscorpius (Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia 25755-2510, USA) ICZN COMPLIANCE OF ELECTRONIC PUBLICATIONS: Electronic (“e-only”) publications are fully compliant with ICZN (International Code of Zoological Nomenclature) (i.e. for the purposes of new names and new nomenclatural acts) when properly archived and registered. All Euscorpius issues starting from No. 156 (2013) are archived in two electronic archives: Biotaxa, http://biotaxa.org/Euscorpius (ICZN-approved and ZooBank-enabled) Marshall Digital Scholar, http://mds.marshall.edu/euscorpius/. (This website also archives all Euscorpius issues previously published on CD-ROMs.) Between 2000 and 2013, ICZN did not accept online texts as "published work" (Article 9.8). -

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY of the PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer Issued by THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Washington, D. C., U.S.A. July 1981 VIRGIN ISLANDS CULEBRA PUERTO RlCO Fig. 1. Map of the Puerto Rican Island Shelf. Rectangles A - E indicate boundaries of maps presented in more detail in Appendix I. 1. Cayo Santiago, 2. Cayo Batata, 3. Cayo de Afuera, 4. Cayo de Tierra, 5. Cardona Key, 6. Protestant Key, 7. Green Key (st. ~roix), 8. Caiia Azul ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN 251 ERRATUM The following caption should be inserted for figure 7: Fig. 7. Temperature in and near a small clump of vegetation on Cayo Ahogado. Dots: 5 cm deep in soil under clump. Circles: 1 cm deep in soil under clump. Triangles: Soil surface under clump. Squares: Surface of vegetation. X's: Air at center of clump. Broken line indicates intervals of more than one hour between measurements. BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwolel, Richard Levins2 and Michael D. Byer3 INTRODUCTION There has been a recent surge of interest in the biogeography of archipelagoes owing to a reinterpretation of classical concepts of evolution of insular populations, factors controlling numbers of species on islands, and the dynamics of inter-island dispersal. The literature on these subjects is rapidly accumulating; general reviews are presented by Mayr (1963) , and Baker and Stebbins (1965) . Carlquist (1965, 1974), Preston (1962 a, b), ~ac~rthurand Wilson (1963, 1967) , MacArthur et al. (1973) , Hamilton and Rubinoff (1963, 1967), Hamilton et al. (1963) , Crowell (19641, Johnson (1975) , Whitehead and Jones (1969), Simberloff (1969, 19701, Simberloff and Wilson (1969), Wilson and Taylor (19671, Carson (1970), Heatwole and Levins (1973) , Abbott (1974) , Johnson and Raven (1973) and Lynch and Johnson (1974), have provided major impetuses through theoretical and/ or general papers on numbers of species on islands and the dynamics of insular biogeography and evolution. -

Us Caribbean Regional Coral Reef Fisheries Management Workshop

Caribbean Regional Workshop on Coral Reef Fisheries Management: Collaboration on Successful Management, Enforcement and Education Methods st September 30 - October 1 , 2002 Caribe Hilton Hotel San Juan, Puerto Rico Workshop Objective: The regional workshop allowed island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to identify successful coral reef fishery management approaches. The workshop provided the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force with recommendations by local, regional and national stakeholders, to develop more effective and appropriate regional planning for coral reef fisheries conservation and sustainable use. The recommended priorities will assist Federal agencies to provide more directed grant and technical assistance to the U.S. Caribbean. Background: Coral reefs and associated habitats provide important commercial, recreational and subsistence fishery resources in the United States and around the world. Fishing also plays a central social and cultural role in many island communities. However, these fishery resources and the ecosystems that support them are under increasing threat from overfishing, recreational use, and developmental impacts. This workshop, held in conjunction with the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force Meeting, brought together island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel to compare methods that have been successful, including regulations that have worked, effective enforcement, and education to reach people who can really effect change. These efforts were supported by Federal fishery managers and scientists, Puerto Rico Sea Grant, and drew on the experience of researchers working in the islands and Florida. The workshop helped develop approaches for effective fishery management strategies in the U.S. Caribbean and recommended priority actions to the U.S. -

Forest Inventory and Analysis National Core Field Guide

National Core Field Guide, Version 5.1 October, 2011 FOREST INVENTORY AND ANALYSIS NATIONAL CORE FIELD GUIDE VOLUME I: FIELD DATA COLLECTION PROCEDURES FOR PHASE 2 PLOTS Version 5.1 National Core Field Guide, Version 5.1 October, 2011 Changes from the Phase 2 Field Guide version 5.0 to version 5.1 Changes documented in change proposals are indicated in bold type. The corresponding proposal name can be seen using the comments feature in the electronic file. • Section 8. Phase 2 (P2) Vegetation Profile (Core Optional). Corrected several figure numbers and figure references in the text. • 8.2. General definitions. NRCS PLANTS database. Changed text from: “USDA, NRCS. 2000. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 1 January 2000). National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA 70874-4490 USA. FIA currently uses a stable codeset downloaded in January of 2000.” To: “USDA, NRCS. 2010. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 1 January 2010). National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA 70874-4490 USA. FIA currently uses a stable codeset downloaded in January of 2010”. • 8.6.2. SPECIES CODE. Changed the text in the first paragraph from: “Record a code for each sampled vascular plant species found rooted in or overhanging the sampled condition of the subplot at any height. Species codes must be the standardized codes in the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) PLANTS database (currently January 2000 version). Identification to species only is expected. However, if subspecies information is known, enter the appropriate NRCS code. For graminoids, genus and unknown codes are acceptable, but do not lump species of the same genera or unknown code. -

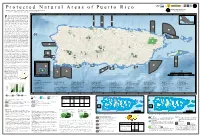

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

Guide to Theecological Systemsof Puerto Rico

United States Department of Agriculture Guide to the Forest Service Ecological Systems International Institute of Tropical Forestry of Puerto Rico General Technical Report IITF-GTR-35 June 2009 Gary L. Miller and Ariel E. Lugo The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and national grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD).To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Authors Gary L. Miller is a professor, University of North Carolina, Environmental Studies, One University Heights, Asheville, NC 28804-3299. -

Rhesus Macaque Eradication to Restore the Ecological Integrity of Desecheo National Wildlife Refuge, Puerto Rico

C.C. Hanson, T.J. Hall, A.J. DeNicola, S. Silander, B.S. Keitt and K.J. Campbell Hanson, C.C.; T.J. Hall, A.J. DeNicola, S. Silander, B.S. Keitt and K.J. Campbell. Rhesus macaque eradication to restore the ecological integrity of Desecheo National Wildlife Refuge, Puerto Rico Rhesus macaque eradication to restore the ecological integrity of Desecheo National Wildlife Refuge, Puerto Rico C.C. Hanson¹, T.J. Hall¹, A.J. DeNicola², S. Silander³, B.S. Keitt¹ and K.J. Campbell1,4 ¹Island Conservation, 2100 Delaware Ave. Suite 1, Santa Cruz, California, 95060, USA. <chad.hanson@ islandconservation.org>. ²White Buff alo Inc., Connecticut, USA. ³U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Caribbean Islands› NWR, P.O. Box 510 Boquerón, 00622, Puerto Rico. 4School of Geography, Planning & Environmental Management, The University of Queensland, St Lucia 4072, Australia. Abstract A non-native introduced population of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) was targeted for removal from Desecheo Island (117 ha), Puerto Rico. Macaques were introduced in 1966 and contributed to several plant and animal extirpations. Since their release, three eradication campaigns were unsuccessful at removing the population; a fourth campaign that addressed potential causes for previous failures was declared successful in 2017. Key attributes that led to the success of this campaign included a robust partnership, adequate funding, and skilled fi eld staff with a strong eradication ethic that followed a plan based on eradication theory. Furthermore, the incorporation of modern technology including strategic use of remote camera traps, monitoring of radio-collared Judas animals, night hunting with night vision and thermal rifl e scopes, and the use of high-power semi-automatic fi rearms made eradication feasible due to an increase in the probability of detection and likelihood of removal. -

Redalyc.A Study of the Dry Forest Communities in the Dominican

Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências ISSN: 0001-3765 [email protected] Academia Brasileira de Ciências Brasil GARCÍA-FUENTES, ANTONIO; TORRES-CORDERO, JUAN A.; RUIZ-VALENZUELA, LUIS; LENDÍNEZ-BARRIGA, MARÍA LUCÍA; QUESADA-RINCÓN, JUAN; VALLE- TENDERO, FRANCISCO; VELOZ, ALBERTO; LEÓN, YOLANDA M.; SALAZAR- MENDÍAS, CARLOS A study of the dry forest communities in the Dominican Republic Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, vol. 87, núm. 1, marzo, 2015, pp. 249-274 Academia Brasileira de Ciências Rio de Janeiro, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=32738838023 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências (2015) 87(1): 249-274 (Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences) Printed version ISSN 0001-3765 / Online version ISSN 1678-2690 http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765201520130510 www.scielo.br/aabc A study of the dry forest communities in the Dominican Republic ANTONIO GARCÍA-FUENTES1, JUAN A. TORRES-CORDERO1, LUIS RUIZ-VALENZUELA1, MARÍA LUCÍA LENDÍNEZ-BARRIGA1, JUAN QUESADA-RINCÓN2, FRANCISCO VALLE-TENDERO3, ALBERTO VELOZ4, YOLANDA M. LEÓN5 and CARLOS SALAZAR-MENDÍAS1 1Departamento de Biología Animal, Biología Vegetal y Ecología, Facultad de Ciencias Experimentales, Universidad de Jaén, Campus Las Lagunillas, s/n, 23071 Jaén, España 2Departamento de Ciencias Ambientales, Facultad de Ciencias Ambientales y Bioquímica, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Avda. Carlos III, s/n, 45071 Toledo, España 3Departamento de Botánica, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Granada, Campus de Fuentenueva, Avda. -

Mission to the Caribbean-Final Report

THE STATUS OF CACTOBLASTIS CACTORUM (LEPIDOPTERA: PYRALIDAE) IN THE CARIBBEAN AND THE LIKELIHOOD OF ITS SPREAD TO MEXICO Report* to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Joint FAO/IAEA Division of Nuclear Techniques in Food and Agriculture and the Plant Health General Directorate, Mexico (DGSVB/SAGARPA) as part of the TC Project MEX/5/029 Helmuth G. Zimmermann¹, Mayra Pérez Sandi y Cuen² and Arturo Bello Rivera³ ¹Helmuth Zimmermann & Associates, Pretoria, South Africa. ² Consultant to SAGARPA, Mexico D.F. ³SAGARPA, Plant Health, Mexico D.F. © IAEA 2005 The islands surveyed during this mission included: Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Antigua, Montserrat, St. Kitts, Jamaica and Grand Cayman (funded by the IAEA). *This report also includes information and conclusions by the second author (Mayra Perez Sandi) who visited and surveyed the following islands in the Lesser Antilles: Guadeloupe, Dominique, Trinidad and Tobago, Chacachacare, Grenada, St. Vicent, Bequia, Barbados, St. Lucia, Martinique and Chevalier. This part of the survey was funded by PRONATURA NORESTE, FMCN Y USAID. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The cactus moth, Cactoblastis cactorum (Berg) , which has become the textbook example of successful biological weed control of invasive Opuntia species in many countries, including some Caribbean islands, is now threatening not only the lucrative cactus pear industry in Mexico, but also the rich diversity of all Opuntia species in most of the North American mainland. Already threatened species in Mexico could go extinct. The moth is now present on most Caribbean islands as a consequence of mostly deliberate or accidental introductions by man, or through natural spread. Although there is convincing evidence that Cactoblastis reached Florida inadvertently conveyed by the nursery trade, there also exists the slight possibility of natural spread and by means of cyclonic weather events. -

Amaranthaceae

FLORA DE COLOMBIA MONOGRAFÍA NO. 23 AMARANTHACEAE CARLOS ALBERTO AGUDELO-H. Herbario HUQ, Universidad del Quindío, Armenia, Colombia. [email protected] Editores: JULIO BETANCUR GLORIA GALEANO JAIME AGUIRRE-C. INSTITUTO DE CIENCIAS NATURALES FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE COLOMBIA BOGOTÁ, D. C., COLOMBIA 2008 ©INSTITUTO DE CIENCIAS NATURALES UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE COLOMBIA APARTADO 7495, BOGOTÁ, COLOMBIA ©CARLOS ALBERTO AGUDELO-H. EDITORES: Julio Betancur Gloria Galeano Jaime Aguirre-C. ASISTENTES EDITORIALES: Laura Clavijo Alejandro Zuluaga DIAGRAMACIÓN: Liliana P. Aguilar-G. IMPRESIÓN: ARFO Editores e Impresores Ltda. Cra 15 No. 54 - 32 [email protected] Bogotá, Colombia ISSN 0120-4351 CÍTESE COMO: Agudelo-H., C. A. Amaranthaceae. Flora de Colombia No. 23. Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Bogotá D. C. Colombia. 138 p. Impreso en Colombia - Printed in Colombia, Bogotá, septiembre de 2008 Agudelo-H.: Amaranthaceae 3 DE LOS EDITORES DE FLORA DE COLOMBIA Nos complace entregar a la comunidad científica el número veintitrés de la Serie Flora de Colombia, el cual contiene el tratamiento de la familia Amaranthaceae para el país. La familia Amaranthaceae contiene cerca de 70 géneros y un millar de especies que se distribuyen por casi todo el planeta, exceptuando la región ártica, pero está más diversificada hacia las regiones tropicales. En América tropical está representada por 20 géneros y 300 especies aproximadamente, algunas de las cuales son introducidas y se comportan como malezas. Sin embargo, otras tantas especies se utilizan como plantas ornamentales o como fuente de medicamentos a nivel local. En este tratamiento para Colombia se presentan 14 géneros y 49 especies, por lo que esperamos que esta obra sea de gran utilidad para el conocimiento de esta importante familia en Colombia y los países vecinos, y que se convierta en una herramienta útil para la identificación y conocimiento de las especies. -

Digenetic Trematodes of Marine Fishes of the Western and Southwestern Coasts of Puerto Rico

Proc. Helminthol. Soc. Wash. 52(1), 1985, pp. 85-94 Digenetic Trematodes of Marine Fishes of the Western and Southwestern Coasts of Puerto Rico WILLIAM G. DYER,' ERNEST H. WILLIAMS, JR.,2 AND LUCY BUNKLEY WiLLiAMS2 1 Department of Zoology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois 62901 and 2 Department of Marine Science, University of Puerto Rico, Mayaguez, Puerto Rico 00708 ABSTRACT: A comprehensive study was made in coastal waters of western and southwestern Puerto Rico from 1974 to 1984 to inventory the digenetic flukes of marine fishes. A total of 1,019 fishes representing 76 families, 155 genera, and 252 species were examined. Nineteen families of digenetic flukes representing 52 genera and 66 species were recorded, including 11 digenea not previously known from Puerto Rico. Four new host records were established. Most infections were of a single species and although prevalence and intensity were low, host specificity was high. Major contributions to knowledge of the di- The 66 species of flukes detected represented 19 genetic flukes of marine fishes of Puerto Rico families and 52 genera (Table 1). Of the 70 species stem from the early studies of Cable (1954a, b, of fishes that were infected, 56 (80%) harbored 1956a, b), LeZotte (1954), and the more recent 1 species of digenetic fluke, 8 species (11.4%) 2, comprehensive report by Siddiqi and Cable and 2 species (2.9%) with 3 to a maximum of 5 (1960). species of flukes. Fish negative for digeneans are Between April 1974 and January 1984 addi- listed in Appendix 1. tional data were obtained from examining 1,019 The intensity of a given species ranged from marine fishes representing 69 families of bony 1 to 100 flukes per host. -

Q2 2005 Online Version

B/W Logo THETHE FIELDFIELD NATURALISNATURALISTT QuarterlyQuarterly BulletinBulletin ofof thethe TrinidadTrinidad andand TobagoTobago FieldField Naturalists’Naturalists’ ClubClub April- June Nos.2/2005 The Other Side of Caura Valley Jo-Anne Nina Sewlal and Christopher K. Starr The image that first springs to mind of most people when they hear the name “Caura Valley” is that of a “river lime”. Well river limes are not the main events in Caura Valley. The Nepuyo Carib Amerindians, who originally occupied Caura Valley, gave the valley its name which means “heavily wooded area.” So it comes as no surprise that this area is also fre- quented by hunters. Forested areas also make good sites to look for spiders and insects as well as provide a pleasing backdrop for a nature hike or walk. This collection of short descriptions is intended to give readers an idea of the potential of the Caura Valley as a destination for exploring nature, whether you enjoy long hikes or short nature rambles. Like all valleys in the Northern Range, the Caura Valley has many smaller side valleys. One such valley is Tucaragua Valley which we decided to explore in late January. This small side valley is located 7km up the Caura Royal Road. The ac- tual trail starts approximately 1km up the Tucaragua Valley Road. After crossing a stream one enters a wide, well maintained dirt road. This road is similar to that which leads to the Maracas waterfall after one leaves the parking lot. Here we observed a swarm of midges using an abandoned spider web as a resting site and, nests of the solitary wasp Trypoxylon manni dotted along the earth banks.