Notions on Community, Locality and Changing Space in the Dublin Docklands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Spencer Dock

ARGUABLY THE MOST PROMINENT OFFICE BUILDING IN A LOCATION SYNONYMOUS WATCH THE VIDEO WITH ICONIC DUBLIN LANDMARKS, GLOBAL LEADERS AND A THRIVING LOCAL ECONOMY IRELAND’S LARGEST OFFICE INVESTMENT 2 3 THE HEADLINES FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY ON THE INSTRUCTION OF: The Joint Receiver, REAL ESTATE Luke Charleton & David Hughes of EY Investment & Management • Grade A office building extending to approximately 21,054 sq m (226,624 sq ft) • 100 basement car parking spaces • Let to PwC, the largest professional services firm in Ireland • Long unexpired lease term, in excess of 16.5 years • Passing rent of €11,779,241 per annum • Strong reversionary potential (current passing rent of approximately €50 per sq ft) • Upward only rent reviews (next review April 2017) • Tenant unaffected by the sale www.onespencerdock.com 4 5 A PRIME WATERFRONT LOCATION 6 7 DOCKLANDS TRAIN STATION 3 GARDINER STREET 5 9 CONNOLLY BUS ROUTE MARLBOROUGH TALBOT STREET BUSARAS AMIENS STREET 4 2 MAYOR SQUARE 1 O’CONNELL GPO O’CONNELL STREET IFSC SPENCER DOCK POINT VILLAGE ABBEY STREET NORTH DOCKS CUSTOM HOUSE QUAY DUBLIN BIKES PROPOSED DOCKLANDS DUBLIN BIKES RAPID TRANSIT QUALITY DUBLIN BIKES NORTH WALL QUAY BUS CORRIDOR DUBLIN BIKES BUS ROUTE DUBLIN BIKES DUBLIN BIKES RIVER LIFFEY SAMUEL DUBLIN BIKES BECKETT 6 CITY QUAY TARA STREET DUBLIN BIKES BRIDGE PROPOSED LINK D’OLIER STREET BRIDGE SIR JOHN ROGERSONS QUAY WESTMORELAND MOSS STREET DUBLIN BIKES SOUTH TRINITY DUBLIN BIKES DUBLIN BIKES DOCKS PEARSE STREET TARA STREET DUBLIN BIKES GRAND CANAL DUBLIN BIKES HANOVER QUAY SQUARE -

Tall Buildings in Dublin

ctbuh.org/papers Title: The Need for Vision: Tall Buildings in Dublin Author: Brian Duffy, Associate, Traynor O'Toole Architects Subject: Urban Design Keywords: Development Master Planning Urban Sprawl Vertical Urbanism Publication Date: 2008 Original Publication: CTBUH 2008 8th World Congress, Dubai Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Brian Duffy The Need for Vision: Tall Buildings in Dublin Brian Duffy Associate, Traynor O’Toole Architects – 49 Upper Mount Street, Dublin 2, Ireland Abstract The Celtic Tiger economy in Ireland has dramatically changed the substance of life in Ireland within a very short space of time. Whilst the infrastructure has struggled to keep up, the urban realm has begun the process of rapidly transforming Dublin from a low rise city of urban sprawl, to a densely woven contemporary modern environment. The appetite to build tall is tempered by an apprehensive planning policy, that reflects the cautious mood of the general public. Such apprehension restricts the possibility of creating an of-its-time City that meets it demands sustainably, whilst fulfilling its high aspirations. The paper examines planning policies and how Dublin architects have pursued tall buildings, most typically in the city centre. This is then contrasted with an alternative approach on the edge of the city, where one major landowner and [email protected] design team have proposed an entire masterplanning vision, premised on the inclusion of tall buildings. This untypical approach yields notable success and, in doing so, highlights the need for a more proactive and interactive approach to Biography Briantall building Duffy qualifiedstrategic planningfrom Queens on behalf University of architects, Belfast, developers Northern Ireland, and planners before alike. -

Mission Statement We Will Develop Dublin Docklands Into a World-Class

Presentation to Delegation from Stockholm 25th April, 2007 Paul Maloney, CEO 1. THE DOCKLANDS PROJECT BACK IN 1987 • Population at 16,000 • Dereliction • Economic deprivation • Educational disadvantage 1. THE DOCKLANDS PROJECT CUSTOM HOUSE DOCKS / IFSC 1997 22.0 hectares 1. THE DOCKLANDS PROJECT STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES Accelerating physical rollout Achieving architectural legacy Fulfilling the potential of the Docklands Realising quality of life Creating a sense of place Physical Development…. 2. PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT DOCKLANDS NORTH LOTTS Commercial Space Completed 17,288m2 2002 Permitted 62,402m2 Housing units 2007 Completed 343 Permitted 1,606 2. PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT GRAND CANAL DOCK Commercial Space 2 2002 Completed 55,412m Permitted 184,018m2 Housing units 2007 Completed 910 Permitted 1,516 2. PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT NEW TENANTS MOVING INTO DOCKLANDS ESRI Dillon Eustace O2 Mason Hayes Curran PWC Mason Hayes Curran McCann Fitzgerald Google Beauchamps Fortis Bank Google PFPC Irish Taxation Institute Anglo Irish Bank MOPS O’Donnell Sweeney Arups U2 Tower Arups 2. PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT POINT VILLAGE Point Village 2. PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT PLANNING IN NORTH LOTTS Proposed new Masterplan 2. PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT POOLBEG PENINSULA New City Quarter • Over 100 acres • Public transport infrastructure • Urban sustainable development • Amenities, cultural & community interventions Review of Heights and Densities 2. PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT STREETSCAPES Price Waterhouse Coopers McCann Fitzgerald Forbe’s Quay Google Architectural Legacy… 3. Architectural Legacy Dublin’s Architectural Gateway U2 Tower The WatchTower 3. Architectural Legacy SAMUEL BECKETT BRIDGE 3. Architectural Legacy NATIONAL CONFERENCE CENTRE AT SPENCER DOCK 3. Architectural Legacy chq - CONSERVATION 3. Architectural Legacy ROYAL CANAL LINEAR PARK 3. Architectural Legacy GRAND CANAL SQUARE/LIBESKIND THEATRE Realising Quality of Life… 4. -

Eastside Docklands - Construction and Unemployment Changing the Narrative

2020 Construction and Unemployment Changing the Dublin Narrative Eastside + Docklands Local Employment Services A project of St. Andrew’s Resource Centre + Inner City Renewal Group Report on Dublin City Construction Skills Project 2020 Eastside Docklands - Construction and Unemployment Changing the Narrative Employment and Unemployment Trends in Ireland and Impact on Young Workers Increase in Since 2017 Ireland has continued to experience The scale of youth unemployment, and proportion of long- a strengthening labour market, with further its potential for long-term damage to the term unemployed improvements in the number of labour market employment prospects of individuals, highlights indicators. In 2017, the unemployment level the need for policies to actively address youth 2007 declined by 37,000, while the unemployment and young people unemployed. This report rate declined by 1.7% to an annual average deals with the impact on a specified area and of 6.7%. client cohorts. As the thinking about how best 27% to address the issue the youth and Long term The unemployment rate in Ireland is still higher unemployment rates in specific communities than in the period from 2002-2007.1 In Ireland were considered. by 2018, there were 36,000 more people unemployed (and 23,000 more long-term unemployed), than there had been in 2005, with evidence that the employment rate is still far Long Term Unemployed from recovering from the impact of the financial As the development of the project continued 2010 crisis. As is noted by Ciarán Nugent of NERI, this the figures were stark. While the wider lack of recovery in the unemployment figures unemployment rate has declined by 1.7%, it is is due, for the most part, to the collapse of of note that the rate for long term unemployed employment for younger cohorts, particularly declined by only 0.8% to 2.5% in quarter 4 for young men. -

Sdz Docklands Study Maps

1 DRAFT SDZ DOCKLANDS STUDY MAPS PUBLIC REALM MASTERPLAN FOR THE NORTH LOTTS & GRAND CANAL DOCK SDZ PLANNING SCHEME 2014 2 Public Realm Masterplan North Lotts & Grand Canal Dock Dublin City Council working group Deirdre Scully (planner) Jeremy Wales (architect) Jason Frehill (planner) Seamus Storan (engineer) Peter Leonard (parks) REDscape Landscape & Urbanism with Howley Hayes, Scott Cawley, Build Cost, O Connor Sutton Team REDscape Landscape & Urbanism: Howley Hayes Architects (heritage) : Fergal Mc Namara. Patrick Mc Cabe, landscape architect Scott Cawley Ecologists: (ecology) Paul Scott. David Habets, landscape designer O Connor Sutton Cronin Engineers: (PSDP) Anthony Horan. Joanne Coughlan, landscape architect Build Cost Quantity Surveyors: Liam Langan. Antoine Fourrier, landscape designer Andreas Mulder, urban designer Cover image: Perspective of the liffey, North Lotts and Grand Canal Dock. Legal This report contains several images and graphics based on creative representations. No legal rights can be given to these representations. All images have been accredited. Where the source is not clear, all efforts have been made to clarify the source. Date: January 2016 Dublin City Council Prepared by REDscape Landscape & Urbanism. 77 Sir John Rogerson’s Quay, Dublin 2. www.redscape.ie 3 Content Parks, squares, play areas Public transport Pedestrian routes Bicycle Routes Car road hierarchy Transport connections Underground infrastructure Tree structure Cultural and community facilities Water activities and facilities Creative hubs Urban development North Lotts shadow study North Lotts underground infrastructure 4 Public Realm Masterplan public green spaces North Lotts & Grand Canal Dock square & plaza football ptich proposed public green spaces 8 - 20+ y/o proposed square & plaza playground open air sport Play Ground Mariners Port Station Square Middle Park 2 - 7 y/o Point Square Pocket Park Source : Comhairle Cathrach Bhaile Átha Cliath - Dublin City Council, Maps & Figures,North Lotts & Grand Canal Dock Planning Scheme, 5th November 2013, Fig. -

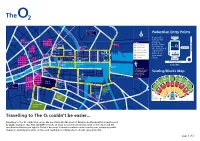

Travelling to the O2 Couldn't Be Easier

Colour palette Primary colour Pantone CMYK RGB Websafe Gardiner St Upper Port land Five Clontarf Road ll Row hi Lamps Ea r Dart Station s Pedestrian Entry Points t W ROY 1km / 14min walk all Rd l Summe A L unne CANAL T rt Please take B t o S P per 20 27 116 145 note of the Up Parnel B A B A PMS 2747 C100 M094 Y000 K029 R000 G000 B102 Hex 000066 27C 29 31 31 32B Seville Plac B Gardiner St 40 40 120 123 A A Amiens East Rd LEGEND entrance l Sq East 42 42B 43 51 53 St Connolly A points. These Secondary colours 53 53 142 ll Rd Dorset St 90 127 129 130 142 e Rail / Dart Line A Station t Wall Rd 11 11 B s Parnell Docklands correlate to Lower Wa A Ea LUAS Red Line PMS 2768 C095 M081 Y000 K059 R025 G034 B079 Hex 000033 13 13 14 Station the designated A 93 151 O’Connell St 16 16 19 LUAS Sheriff St Upper LUAS Green Line Sheriff St Lwr East A A entry point 40C 48 123 PMS 2945 C100 M038 Y000 K015 R000 G088 B150 Hex 003399 Mayor Pedestrian Route Taxi Rank printed on 747748 Square Commons St The Guild St Bus Route Stop Busáras your event PMS 2925 C087 M023 Y000 K000 R000 G144 B208 Hex 3399CC 2 3 4 5 Spire Mayor St Lower 4 5 Car Park Parnell St A A chq Convention ticket. B A 7 7 8 10 10 A Castleforbes Rd D 7 B 7 8 53 PMS 2915 C060 M011 Y000 K000 R101 G180 B228 Hex 66CCFF D New Wapping St A Centre 14A 16 16 19 38 151 A A D A C North Wall Quay 38C 46B 46E 48 58 Quay 93 90 North Wall Quay North Wall Quay C Abbey St Lower House A Custom PMS 290 C016 M000 Y000 K000 R190 G217 B237 Hex * C Capel St 63 121 122 145 746 38 38 Sean O’Casey Samuel Beckett 151 Foot-Bridge -

Docklands Going Wrong?

Docklands Going Wrong? Prof. Andrew MacLaran Department of Geography, Trinity College Dublin [email protected] Dr. Sinéad Kelly, Department of Geography, Maynooth University [email protected] Economic base • Declining industrial land uses, 1966-85 – Closures – Suburbanisation of manufacturing & warehousing Population & housing • Long-term pop. decline – 1911 pop 240,000 – 1979 pop 104,000 • Remaining population – Low level of skills – High unemployment – Small hh. & elderly • Poor housing (1974) – 40% lack bath – 25% blgs in poor condition – Poorly maintained local- authority dwellings 1985: 600 cleared sites & derelict buildings in the CBD itself (metered parking area) Combined area of 160 acres (65ha.) Derelict land & vacant buildings 1985 Docklands: on the eastern edge of the CBD Disused wet docks; derelict land; eyesore industries; scrap metal dealing; live animal exports; truck haulage yards; surface car parking etc. But did give some employment relevant to the low skills levels of local residents Pamplona ? Unemployment • Changing cargo-handling (pallets & containers) required only 10% of original labour force • Unemployment (mid 1980s) – Inner-city @ 35% – Sheriff Street @ 83% (social housing) Sheriff Street (social housing) Urban Renewal Act (1986) & Finance Act (1987) • Created a package of incentives aimed at encouraging development • Aims: – To stimulate private sector interest in inner-city renewal – To boost employment construction sector which had an unemployment rate of 45% • Strategic alliances forged between urban planners -

Line C Connolly to the Point Depot Chapter Page

Dublin Light Rail Environmental impact Statement Line C Connolly to The Point Depot Chapter Page 1: Introduction 3 2: Public Consultation 12 3: Consideration of Alternative Routes 21 4: Luas Red Line Extension: Project Description 34 5: Planning and Land Use Context 43 6: Socio Economic Context 53 7: Traffic and Transportation 62 8: Ecological Resources 85 9: Soil 90 10: Water 95 11: Noise and Vibration 99 12: Electromagnetic Effects 113 13: Air Quality and Climate 116 14: Landscape and Visual 126 15: Cultural Heritage 149 16: Impact Interactions 161 17: Statement of Assessment 167 Annex A: Landscape Insertion Plans 168 Annex B: RPA Consultation Newsletter 174 Annex C: Supporting Information on Climate and Air Quality 176 1 Availability of the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) Copies of the EIS including the Non Technical Summary are available for inspection and pur- chase at the following locations: Railway Procurement Agency Parkgate Business Centre, Parkgate Street, Dublin 8. Dublin Transportation Office 69 – 71 St. Stephens Green, Hainault House, Dublin 2. The EIS is also available to download (free of charge) through the RPA website: www.rpa.ie Copies of this EIS can be purchased for a sum of ¤15.00 each; A CD version of the EIS can be purchased for a sum of ¤5.00; Photomontage showing proposed Luas Stop on Mayor Street Copies of the Non Technical Summary of this EIS may be purchased for a sum of ¤3.00 each at the above locations. 2 INTRODUCTION • to identify measures that should be taken to mit- sultants, ERM takes responsibility for the informa- igate potential adverse impacts; tion and recommendations contained in this EIS 1.1 OBJECTIVES OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT document. -

Sir John Rogerson's Quay, Dublin 2

SIR JOHN ROGERSON’S QUAY, DUBLIN 2 THE DOCKLANDS RE-IMAGINED 80,000 sq ft of exceptional office space, blending original warehouse features with spectacular modern architecture and design. Overlooking the water and located in the centre of Dublin’s docklands, home to the most successful and innovative global companies. 1 WHERE GLASS MEETS WATER A reflective design connecting innovation with history, the Tropical Fruit Warehouse is a truly unique office environment which has been crafted to maximise views over the River Liffey and Dublin’s skyline. 2 3 ‘A SENSE OF FLOATING ABOVE THE RIVER’ PAUL O’BRIEN, HENRY J LYONS ARCHITECTS ‘ The unique context of the site provided an opportunity to create an architectural set-piece – a contrast of old and new. The resulting design is a composition consisting of interconnecting rectangular buildings, a grounded historical warehouse building beneath, and a modern, cantilevered floating structure above. The modern building is an uncompromising design of a ‘twin skin’ full glass box envelope, with a view out over the bridge. Externally, the glass box facades create the sense of a transparent ‘jewel’ floating above the heavier masonry facades of the historic warehouse below. Internally, the views out of the floors give a sense of floating above the river.’ 4 5 HISTORIC TIMELINE Marine School Founded for the education of the orphans and children of distressed seamen, the Marine School sat on River God Keystones 1766 the site of the Tropical Fruit Warehouse. The two granite figureheads representing Anna Livia and Atlantic that hang over the doors of the Tropical Fruit Warehouse are the original keystones taken from the old Carlisle Bridge (the structure predating O’Connell Bridge) in 1870. -

Archaeology & Historical Public Realm Survey.Pdf

SDZ Docklands Archaeology & Historical Public 1 Realm Survey DRAFT DOCKLANDS SDZ : ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORICAL PUBLIC REALM SURVEY PUBLIC REALM MASTERPLAN FOR THE NORTH LOTTS & GRAND CANAL DOCK SDZ PLANNING SCHEME 2014 2 Public Realm Masterplan North Lotts & Grand Canal Dock Content Dublin City Council working group Deirdre Scully (planner) Docklands SDZ: Archaeology (2012) by Ruth Johnson PhD FSA MIAI Jeremy Wales (architect) Jason Frehill (planner) Historical Public Realm Survey (2016) by Howley Hayes Architects Seamus Storan (engineer) Ruth Johnson (archaeologist) REDscape Landscape & Urbanism with Team REDscape Landscape & Urbanism: Howley Hayes Architects (heritage) : Fergal Mc Namara. Patrick Mc Cabe, landscape architect Scott Cawley Ecologists: (ecology) Paul Scott. David Habets, landscape designer O Connor Sutton Cronin Engineers: (PSDP) Anthony Horan. Joanne Coughlan, landscape architect Build Cost Quantity Surveyors: Liam Langan. Antoine Fourrier, landscape designer Andreas Mulder, urban designer Cover image: Perspective of the liffey, North Lotts and Grand Canal Dock. This report contains several images and graphics based on creative representations. No legal rights can be given to these representations. All images have been accredited. Where the source is not clear, all efforts have been made to clarify the source. Date: December 2012 and January 2016 Dublin City Council Prepared by Ruth Johnson (DCC) and Howley Hayes Architects in collaboration with REDscape Landscape & Urbanism. 77 Sir John Rogerson’s Quay, Dublin 2. Ruth -

Hanover Qy Units.Indd

For Sale by Private Treaty (Available in one or more lots) 3 Retail Investment Properties Hanover Quay, Grand Canal Harbour, Dublin 2 (Tenants Not Affected) www.hanoverquaydublin.com Lot 1 – Herbstreet - Units H3 & H4 Lot 2 – Vacant – Unit H2 Lot 3 – Bakers Coffee Company – Units H1 & H5 Lot 4 – The Entire Hanover Quay, Grand Canal Harbour, Dublin 2 Location Dublin South Docklands has undergone substantial rejuvenation including new modern office blocks, residential, retail and cultural developments. The location provides ease of access to public transport facilities including the DART and the Luas red line located on the North Docks and serving The Point Depot to Tallaght and Saggart via the IFSC. The North Docks and the IFSC are easily accessible via the Samuel Beckett. The nearest DART Station is Grand Canal Dock, approximately five minutes walk from the property. Nearby amenities include the Bord Gais EnergyPORTLAND Theatre, ROW the National Convention Centre on the North Docks and the new Marker Hotel. SEVILLE PLACE GARDNER ST LWR AMIENS STREET CONNOLLY MARLBOROUGH ST PARNELL STREET SHERIFF ST LWR O‘CONNELL STREET IFSC To Port Tunnel DART Line SHERRIF STREET CONNOLLY TALBOT ST COMMON ST Luas Red Docklands Line Busaras GEORGES DOCK Gibson BUSÁRAS MAYORS SQUARE IFSC SPENCER DOCK Hotel PARNELL STREET Custom ST Car Clarion National THE POINT CAPEL ST House Jurys Inn HENRY Park College of National Conference CUSTOM HOUSE QUAY Hotel Ireland GUILD ST Centre O2 NORTH WALL QUAY EAST WALL ROAD MARY STREET Luas Red Line EDEN QUAY RIVER LIFFEY -

Changing Cityscapes and the Process of Contemporary Gentrification

NUI MAYNOOTH OllaceU ha kEiranfin Mi H uad OLLSCOIL NA hEIREANN MA NUAD THE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Changing Cityscapes and the Process of Contemporary Gentrification: An examination of the transformation of Ringsend within the context of post-industrial growth in Dublin A thesis submitted by Mary Benson B.A. for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology Department, Faculty of Arts, Research Supervisors: Dr. Mary Corcoran & Professor Michel Peillon Head of Department: Professor Sean O Riain October 2006 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many people. In particular I would like to thank the following: My supervisor Dr. Mary Corcoran, whose belief in me and my work has been a constant throughout this research. I am deeply grateful for your knowledge, advice, support and friendship. Professor Michel Peillon, my second supervisor, whose critical comments on my work were gratefully received. Professor Sean O Riain for your insights and advice. All those who took part in this research for sharing your insights and memories with me. The landscape of Ringsend for revealing so much. To Tach for always being there. Thank you for your love and understanding. To my friends for never letting me lose sight of the ‘big picture’ and for putting up with me for all these years. Finally, this PhD. would not have been possible without the love and support of my family: Michael (Dad), Catherine (Mum), Carol, Philip, Geraldine, Daniel, Jordan, Geòrgie, Sarah, Sean, Liam and Jack. Thank you all for being just who you are. In loving memory of Ann who thought me always to smile.