African American Women Administrators in Higher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of the January 25, 2010, Meeting of the Board of Regents

MINUTES OF THE JANUARY 25, 2010, MEETING OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS ATTENDANCE This scheduled meeting of the Board of Regents was held on Monday, January 25, 2010, in the Regents’ Room of the Smithsonian Institution Castle. The meeting included morning, afternoon, and executive sessions. Board Chair Patricia Q. Stonesifer called the meeting to order at 8:31 a.m. Also present were: The Chief Justice 1 Sam Johnson 4 John W. McCarter Jr. Christopher J. Dodd Shirley Ann Jackson David M. Rubenstein France Córdova 2 Robert P. Kogod Roger W. Sant Phillip Frost 3 Doris Matsui Alan G. Spoon 1 Paul Neely, Smithsonian National Board Chair David Silfen, Regents’ Investment Committee Chair 2 Vice President Joseph R. Biden, Senators Thad Cochran and Patrick J. Leahy, and Representative Xavier Becerra were unable to attend the meeting. Also present were: G. Wayne Clough, Secretary John Yahner, Speechwriter to the Secretary Patricia L. Bartlett, Chief of Staff to the Jeffrey P. Minear, Counselor to the Chief Justice Secretary T.A. Hawks, Assistant to Senator Cochran Amy Chen, Chief Investment Officer Colin McGinnis, Assistant to Senator Dodd Virginia B. Clark, Director of External Affairs Kevin McDonald, Assistant to Senator Leahy Barbara Feininger, Senior Writer‐Editor for the Melody Gonzales, Assistant to Congressman Office of the Regents Becerra Grace L. Jaeger, Program Officer for the Office David Heil, Assistant to Congressman Johnson of the Regents Julie Eddy, Assistant to Congresswoman Matsui Richard Kurin, Under Secretary for History, Francisco Dallmeier, Head of the National Art, and Culture Zoological Park’s Center for Conservation John K. -

Roger Arliner Young (RAY) Clean Energy Fellowship

Roger Arliner Young (RAY) Errol Mazursky (he/him) Clean Energy Fellowship 2020 Cycle Informational Webinar Webinar Agenda • Story of RAY • RAY Fellows Benefits • Program Structure • RAY Host Organization Benefits • RAY Supervisor Role + Benefits • Program Fee Structure • RAY Timeline + Opportunities to be involved • Q&A Story of RAY: Green 2.0 More info: https://www.diversegreen.org/beyond-diversity/ Story of RAY: “Changing the Face” of Marine Conservation & Advocacy Story of RAY: The Person • Dr. Roger Arliner Young (1889 – November 9, 1964) o American Scientist of zoology, biology, and marine biology o First black woman to receive a doctorate degree in zoology o First black woman to conduct and publish research in her field o BS from Howard University / MS in Zoology from University of Chicago / PhD in Zoology from University of Pennsylvania o Recognized in a 2005 Congressional Resolution celebrating accomplishments of those “who have broken through many barriers to achieve greatness in science” o Learn more about Dr. Young: https://oceanconservancy.org/blog/2017/11/29/little-known-lif e-first-african-american-female-zoologist/ Story of RAY: Our Purpose • The purpose of the RAY Clean Energy Diversity Fellowship Program is to: o Build career pathways into clean energy for recent college graduates of color o Equip Fellows with tools and support to grow and serve as clean energy leaders o Promote inclusivity and culture shifts at clean energy and advocacy organizations Story of RAY: Developing the Clean Energy Fellowship Story of RAY: Our Fellow -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

African American Scientists

AFRICAN AMERICAN SCIENTISTS Benjamin Banneker Born into a family of free blacks in Maryland, Banneker learned the rudiments of (1731-1806) reading, writing, and arithmetic from his grandmother and a Quaker schoolmaster. Later he taught himself advanced mathematics and astronomy. He is best known for publishing an almanac based on his astronomical calculations. Rebecca Cole Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Cole was the second black woman to graduate (1846-1922) from medical school (1867). She joined Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, the first white woman physician, in New York and taught hygiene and childcare to families in poor neighborhoods. Edward Alexander Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Bouchet was the first African American to Bouchet graduate (1874) from Yale College. In 1876, upon receiving his Ph.D. in physics (1852-1918) from Yale, he became the first African American to earn a doctorate. Bouchet spent his career teaching college chemistry and physics. Dr. Daniel Hale Williams was born in Pennsylvania and attended medical school in Chicago, where Williams he received his M.D. in 1883. He founded the Provident Hospital in Chicago in 1891, (1856-1931) and he performed the first successful open heart surgery in 1893. George Washington Born into slavery in Missouri, Carver later earned degrees from Iowa Agricultural Carver College. The director of agricultural research at the Tuskegee Institute from 1896 (1865?-1943) until his death, Carver developed hundreds of applications for farm products important to the economy of the South, including the peanut, sweet potato, soybean, and pecan. Charles Henry Turner A native of Cincinnati, Ohio, Turner received a B.S. -

Lorraine Cole

Lorraine Cole: Good afternoon, everyone on behalf of the Offices of Minority and Women Inclusion known as OMWI, welcome to our webinar, Beyond Words, Race, Work, and Allyship amid the George Floyd tragedy. This program is a collaboration between the OMWI directors at the eight federal financial agencies. Lora McCray, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau; Claire Lam, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation; Sharron Levine, Federal Housing Finance Agency; Sheila Clark, Federal Reserve Board; Monica Davy, National Credit Union Administration; Joyce Cofield, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency; Pamela Gibbs, Securities and Exchange Commission; and me Lorraine Cole, US Department of the Treasury. We thank you for being among the 8,500 people joining us this afternoon. Before we begin, we have an invitation and a request for you. First, we invite you to submit questions throughout the session. Use the Q and A tab at the bottom of the screen. Be sure to indicate who your question is directed to. Later in the conversation, Monica will provide audience questions to our speakers. Of course, we won't be able to get to every question, but all questions will be compiled as a resource for other discussions. Secondly, at the end of the session, we ask that you give us your feedback. Use the survey tab at the bottom of your screen to respond to a few quick items. Now, it's my privilege to introduce our speakers. They are two of the nation's preeminent thought leaders on social change, Dr. Johnnetta Betsch Cole and Mr. Howard Ross. When Dr. Johnnetta Cole was featured on the cover of Diversity Woman magazine, the editors put one word next to her name: nonpareil. -

Black History, 1877-1954

THE BRITISH LIBRARY AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY AND LIFE: 1877-1954 A SELECTIVE GUIDE TO MATERIALS IN THE BRITISH LIBRARY BY JEAN KEMBLE THE ECCLES CENTRE FOR AMERICAN STUDIES AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY AND LIFE, 1877-1954 Contents Introduction Agriculture Art & Photography Civil Rights Crime and Punishment Demography Du Bois, W.E.B. Economics Education Entertainment – Film, Radio, Theatre Family Folklore Freemasonry Marcus Garvey General Great Depression/New Deal Great Migration Health & Medicine Historiography Ku Klux Klan Law Leadership Libraries Lynching & Violence Military NAACP National Urban League Philanthropy Politics Press Race Relations & ‘The Negro Question’ Religion Riots & Protests Sport Transport Tuskegee Institute Urban Life Booker T. Washington West Women Work & Unions World Wars States Alabama Arkansas California Colorado Connecticut District of Columbia Florida Georgia Illinois Indiana Kansas Kentucky Louisiana Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Mississippi Missouri Nebraska Nevada New Jersey New York North Carolina Ohio Oklahoma Oregon Pennsylvania South Carolina Tennessee Texas Virginia Washington West Virginia Wisconsin Wyoming Bibliographies/Reference works Introduction Since the civil rights movement of the 1960s, African American history, once the preserve of a few dedicated individuals, has experienced an expansion unprecedented in historical research. The effect of this on-going, scholarly ‘explosion’, in which both black and white historians are actively engaged, is both manifold and wide-reaching for in illuminating myriad aspects of African American life and culture from the colonial period to the very recent past it is simultaneously, and inevitably, enriching our understanding of the entire fabric of American social, economic, cultural and political history. Perhaps not surprisingly the depth and breadth of coverage received by particular topics and time-periods has so far been uneven. -

J. HAYLEY GILLESPIE, Ph.D. Department of Biology, Texas State University, [email protected]

J. HAYLEY GILLESPIE, Ph.D. Department of Biology, Texas State University, [email protected] EDUCATION 2011 University of Texas at Austin (PhD), Ecology, Evolution & Behavior, advisor Dr. Camille Parmesan Dissertation: The ecology of the endangered Barton Springs salamander (Eurycea sosorum). 2005 University of Utah, graduate training in Stable Isotope Analysis (SIRFER lab) (Salt Lake, Utah) 2003 Austin College (BA), Biology (cum laude), minors: Fine Art & Environmental Studies (Sherman, TX) Senior Thesis Art Exhibition: Full Circle, an exhibition about environmental consciousness. TEACHING EXPERIENCE 2017-present Full Time Lecturer, Department of Biology (Modern Biology for non-majors; class size 500), Texas State University (San Marcos, TX) 2017 Visiting Professor of Biology, Huston-Tillotson University Adult Degree Program (Austin, TX) 2016-2017 Visiting Professor of Biology (general biology, and conservation biology courses), Southwestern University (Georgetown, TX) 2016 Visiting Professor of Biology (environmental biology course), Huston-Tillotson University (Austin, TX) 2014-present Informal Class Instructor (Ecology for Everyone, Natural History of Austin, Designing Effective Scientific Presentations), Art.Science.Gallery. (Austin, TX) 2013 Visiting Professor/Artist in Residence in Scientific Literacy, Skidmore College (Saratoga Springs, NY) 2013 Visiting Professor of Biology (ecology course), Southwestern University (Georgetown, TX) 2004-2010 Teaching Assistantships at the University of Texas at Austin (Austin, TX) • 4 semesters of Field Ecology Laboratory with Dr. Lawrence Gilbert at Brackenridge Field Laboratory • 3 semesters of Conservation Biology with Dr. Camille Parmesan • 6 semesters of Introductory Biology for majors with various professors 2003-2004 Middle School Science Teacher / curriculum developer, St. Alcuin Montessori School (Dallas, TX) Spring 2002 Undergraduate Ecology Teaching Assistant with Dr. -

Board of Historic Resources Quarterly Meeting 18 March 2021 Sponsor

Board of Historic Resources Quarterly Meeting 18 March 2021 Sponsor Markers – Diversity 1.) Central High School Sponsor: Goochland County Locality: Goochland County Proposed Location: 2748 Dogtown Road Sponsor Contact: Jessica Kronberg, [email protected] Original text: Central High School Constructed in 1938, Central High School served as Goochland County’s African American High School during the time of segregation. Built to replace the Fauquier Training School which burned down in 1937, the original brick structure of Central High School contained six classrooms on the 11-acre site. The school officially opened its doors to students on December 1, 1938 and housed grades eight through eleven. The 1938 structure experienced several additions over the years. In 1969, after desegregation, the building served as the County’s integrated Middle School. 86 words/ 563 characters Edited text: Central High School Central High School, Goochland County’s only high school for African American students, opened here in 1938. It replaced Fauquier Training School, which stood across the street from 1923, when construction was completed with support from the Julius Rosenwald Fund, until it burned in 1937. Central High, a six-room brick building that was later enlarged, was built on an 11-acre site with a grant from the Public Works Administration, a New Deal agency. Its academic, social, and cultural programs were central to the community. After the county desegregated its schools under federal court order in 1969, the building became a junior high school. 102 words/ 647 characters Sources: Goochland County School Board Minutes Fauquier Training/Central High School Class Reunion 2000. -

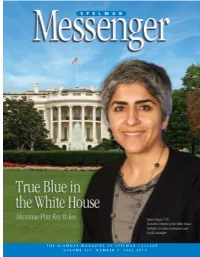

FALL 2010 a Choice to Change the World

THE ALUMNAE MAGAZINE OF SPELMAN COLLEGE VOLUME 121 NUMBER 1 FALL 2010 A Choice to Change the World SPELMAN Messenger EDITOR Jo Moore Stewart COPY EDITOR Janet M. Barstow GRAPHIC DESIGN Garon Hart EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Eloise A. Alexis, C’86 Joyce Davis Tomika DePriest, C’89 Kassandra Kimbriel Jolley Renita Mathis Sharon E. Owens, C’76 Kenique Penn, C’2000 WRITERS Tomika DePriest, C’89 Renita Mathis Lorraine Robertson Angela Brown Terrell PHOTOGRAPHERS Spelman College Archives Curtis McDowell, Professional Photography Julie Yarbrough, C’91 The Spelman Messenger is published twice a year (Fall and Spring) by Spelman College, 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., Atlanta, Georgia 30314- 4399, free of charge for alumnae, donors, trustees and friends of the College. Recipients wishing to change the address to which the Spelman Messenger is sent should notify the editor, giving both old and new addresses. Third-class postage paid at Atlanta, Georgia. Publication No. 510240 CREDO The Spelman Messenger, founded in 1885, is dedicated to participating in the ongoing education of our readers through enlightening articles designed to promote lifelong learning. The Spelman Messenger is the alumnae magazine of Spelman College and is committed to educating, serving and empowering Black women. SPELMAN VOLUME 121, NUMBER 1 Messenger FALL 2010 ON THE COVER Kiran Ahuja, C’93 PHOTO OF KIRAN AHUJA COURTESY OF U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION 8 True Blue in the White House BY TOMIKA DEPRIEST, C’89 Contents 12 Alumnae on Capitol Hill BY RENITA MATHIS 31 Reunion 2010 2 Voices 4 Books & Papers 18 Alumnae Notes 35 In Memoriam It is not the strongest of the species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change. -

Influential Black Biologists

INFLUENTIAL BLACK BIOLOGISTS Lesson Plan Adaptable for all ages and abilities A NOTE TO EDUCATORS AND PARENTS Please take care to review any content before sharing with your students, especially from the external links provided, to make sure it is age appropriate. OBJECTIVES • To learn about influential Black biologists who advanced their field and added to scientific knowledge • To understand the importance of diversity in science • To provide inspiration for future biologists • To provide links to careers advice and guidance WARM-UP As a warm-up exercise, get your pupils to think about as many scientists as they can in one minute. Either have them write this down or do it as a group discussion. How many Scientists on their lists are Black? Discuss with your pupils whether the scientists they came up with represents the make-up of society. Why do they think this is the case? Depending on the age and level of your students, you may wish to draw on points raised in some of the following articles for this discussion: • What is racism - and what can be done about it? (CBBC Newsround) White men still dominate in UK academic science (Nature) • White men’s voices still dominate public science. Here’s how to change this (The Conversation) • The Ideology of Racism: Misusing Science to Justify Racial Discrimination (United Nations) Use the wordsearch (on page 5) provided to start a discussion around which of these Biologists your pupils have or have not heard about. What topics did these scientists research? Which scientific topics sound the most and least interesting to each of the pupil and why? 1/4 RESEARCH Using the “suggested list of people to research further” (on page 4) and the “wordsearch” (on page 5) as a starting point, get your students to select an interesting biologist who inspires them, or who has made a notable discovery. -

Mclean Area Branch AAUW of Virginia

McLean Area Branch AAUW of Virginia April 2012 Volume XLI Number 7 May Dinner Speaker tite for a future branch field trip. Johnnetta Cole Director After beginning her college studies at Fisk University and Smithsonian National completing her undergraduate studies at Oberlin College, Museum of African Art Johnnetta Cole earned a mas- ter’s degree and a doctoral degree in anthropology from Northwestern University. Cole has a long and distin- When was the last time guished career, making history as the first you visited the Muse- African American woman to serve as presi- um of African Art on dent of Spelman College in Georgia in the Mall? Even know where it is? Why is 1987. During her presidency Spelman was African art important to American culture named the number one liberal arts college in and especially to women? the South. Among her many awards is the AAUW Achievement Award, presented at It will be McLean branch’s great fortune the national convention in 1991. Recipient and honor to hear Johnnetta Cole, the muse- of 55 honorary degrees, she is Professor um’s director, at our May 15th dinner. She Emerita of Emory University where she was will tell us why the Smithsonian created this Presidential Distinguished Professor of museum, its important role in American art Anthropology. She was the first African and culture, and why we should all support (Continued on page 8) INSIDE its work. Her talk likely will whet our appe- Branch 2012–13 Officer Candidates 4 April Meeting goes viral in cyberspace. Public Policy 5 Bullying Bullying, including sexual harassment, has AAUW VA Conference 6 Not Just Fun and Games long been an unfortunate part of the climate Connections 6–7 in middle and high schools in the United MPA’s 50th 8 State, even in our own Fairfax County. -

Ronald E. the African American Presence in Physics

Editor: Ronald E. The African American Presence in Physics A compilation of materials related to an exhibit prepared by the National Society of Black Physicists as part of its contribution to the American Physical Society's Centennial Celebration. Editor Ronald E. Mickens Historian, The National Society of Black Physicists March 1999 Atlanta, Georgia Copyright 1999 by Ronald E. Mickens The African American Presence in Physics The African American Presence in Physics Acknowledgments The preparation of this document was supported by funds provided by the following foundations and government agencies: The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation; Corning, Inc.; NASA - Lewis Research Center; The Dibner Fund; the Office of Naval Research; the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center; and the William H. Gates Foundation. Research and production for this document and the related exhibit and brochure were conducted by Horton Lind Communication, Atlanta. Disclaimer Neither the United States government, the supporting foundations nor the NSBP or any of their employees, makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability for responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product or process disclosed, or represents that its 0 does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government, the supporting foundations, or the NSBP. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, the supporting foundations, nor the NSBP and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. in The African American Presence in Physics Contents Foreword vi Part I "Can History Predict the Future?" Kenneth R.