Lorraine Cole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of the January 25, 2010, Meeting of the Board of Regents

MINUTES OF THE JANUARY 25, 2010, MEETING OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS ATTENDANCE This scheduled meeting of the Board of Regents was held on Monday, January 25, 2010, in the Regents’ Room of the Smithsonian Institution Castle. The meeting included morning, afternoon, and executive sessions. Board Chair Patricia Q. Stonesifer called the meeting to order at 8:31 a.m. Also present were: The Chief Justice 1 Sam Johnson 4 John W. McCarter Jr. Christopher J. Dodd Shirley Ann Jackson David M. Rubenstein France Córdova 2 Robert P. Kogod Roger W. Sant Phillip Frost 3 Doris Matsui Alan G. Spoon 1 Paul Neely, Smithsonian National Board Chair David Silfen, Regents’ Investment Committee Chair 2 Vice President Joseph R. Biden, Senators Thad Cochran and Patrick J. Leahy, and Representative Xavier Becerra were unable to attend the meeting. Also present were: G. Wayne Clough, Secretary John Yahner, Speechwriter to the Secretary Patricia L. Bartlett, Chief of Staff to the Jeffrey P. Minear, Counselor to the Chief Justice Secretary T.A. Hawks, Assistant to Senator Cochran Amy Chen, Chief Investment Officer Colin McGinnis, Assistant to Senator Dodd Virginia B. Clark, Director of External Affairs Kevin McDonald, Assistant to Senator Leahy Barbara Feininger, Senior Writer‐Editor for the Melody Gonzales, Assistant to Congressman Office of the Regents Becerra Grace L. Jaeger, Program Officer for the Office David Heil, Assistant to Congressman Johnson of the Regents Julie Eddy, Assistant to Congresswoman Matsui Richard Kurin, Under Secretary for History, Francisco Dallmeier, Head of the National Art, and Culture Zoological Park’s Center for Conservation John K. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

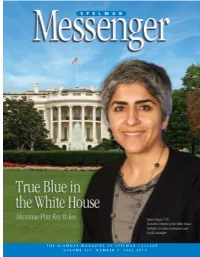

FALL 2010 a Choice to Change the World

THE ALUMNAE MAGAZINE OF SPELMAN COLLEGE VOLUME 121 NUMBER 1 FALL 2010 A Choice to Change the World SPELMAN Messenger EDITOR Jo Moore Stewart COPY EDITOR Janet M. Barstow GRAPHIC DESIGN Garon Hart EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Eloise A. Alexis, C’86 Joyce Davis Tomika DePriest, C’89 Kassandra Kimbriel Jolley Renita Mathis Sharon E. Owens, C’76 Kenique Penn, C’2000 WRITERS Tomika DePriest, C’89 Renita Mathis Lorraine Robertson Angela Brown Terrell PHOTOGRAPHERS Spelman College Archives Curtis McDowell, Professional Photography Julie Yarbrough, C’91 The Spelman Messenger is published twice a year (Fall and Spring) by Spelman College, 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., Atlanta, Georgia 30314- 4399, free of charge for alumnae, donors, trustees and friends of the College. Recipients wishing to change the address to which the Spelman Messenger is sent should notify the editor, giving both old and new addresses. Third-class postage paid at Atlanta, Georgia. Publication No. 510240 CREDO The Spelman Messenger, founded in 1885, is dedicated to participating in the ongoing education of our readers through enlightening articles designed to promote lifelong learning. The Spelman Messenger is the alumnae magazine of Spelman College and is committed to educating, serving and empowering Black women. SPELMAN VOLUME 121, NUMBER 1 Messenger FALL 2010 ON THE COVER Kiran Ahuja, C’93 PHOTO OF KIRAN AHUJA COURTESY OF U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION 8 True Blue in the White House BY TOMIKA DEPRIEST, C’89 Contents 12 Alumnae on Capitol Hill BY RENITA MATHIS 31 Reunion 2010 2 Voices 4 Books & Papers 18 Alumnae Notes 35 In Memoriam It is not the strongest of the species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change. -

Mclean Area Branch AAUW of Virginia

McLean Area Branch AAUW of Virginia April 2012 Volume XLI Number 7 May Dinner Speaker tite for a future branch field trip. Johnnetta Cole Director After beginning her college studies at Fisk University and Smithsonian National completing her undergraduate studies at Oberlin College, Museum of African Art Johnnetta Cole earned a mas- ter’s degree and a doctoral degree in anthropology from Northwestern University. Cole has a long and distin- When was the last time guished career, making history as the first you visited the Muse- African American woman to serve as presi- um of African Art on dent of Spelman College in Georgia in the Mall? Even know where it is? Why is 1987. During her presidency Spelman was African art important to American culture named the number one liberal arts college in and especially to women? the South. Among her many awards is the AAUW Achievement Award, presented at It will be McLean branch’s great fortune the national convention in 1991. Recipient and honor to hear Johnnetta Cole, the muse- of 55 honorary degrees, she is Professor um’s director, at our May 15th dinner. She Emerita of Emory University where she was will tell us why the Smithsonian created this Presidential Distinguished Professor of museum, its important role in American art Anthropology. She was the first African and culture, and why we should all support (Continued on page 8) INSIDE its work. Her talk likely will whet our appe- Branch 2012–13 Officer Candidates 4 April Meeting goes viral in cyberspace. Public Policy 5 Bullying Bullying, including sexual harassment, has AAUW VA Conference 6 Not Just Fun and Games long been an unfortunate part of the climate Connections 6–7 in middle and high schools in the United MPA’s 50th 8 State, even in our own Fairfax County. -

African American Women Administrators in Higher Education

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2004 African American women administrators in higher education: exploring the challenges and experiences at Louisiana public colleges and universities Germaine Monquenette Becks-Moody Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Becks-Moody, Germaine Monquenette, "African American women administrators in higher education: exploring the challenges and experiences at Louisiana public colleges and universities" (2004). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2074. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2074 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN ADMINISTRATORS IN HIGHER EDUCATION: EXPLORING THE CHALLENGES AND EXPERIENCES AT LOUISIANA PUBLIC COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Educational Leadership, Research, and Counseling by Germaine Monquenette Becks-Moody B.P.A, Grambling State University, 1990 M.P.A, Louisiana State University, 1992 December, 2004 Acknowledgements Thanks to the 10 women who took time from busy schedules to make this project a success. Although I can only acknowledge them by pseudonyms, I would like to thank Ruby, Lynn, Marie, Jean, Victoria, Rosa, Lisa, Patricia, Bernice, and Kara for their valuable time and willingness to share their stories. -

Higher Education's Worldly Wisdom

Higher Education’s Worldly Wisdom: Global Reach and What We Teach Executive Summary Yale School of Management, Evans Hall • January 30, 2018 LEADERSHIP PARTNERS Table of Contents Welcome & Overview 4 Jeffrey A. Sonnenfeld, Senior Associate Dean, Yale School of Management Peter Salovey, 23rd President, Yale University Meeting or Missing the Mission: American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ Commission on the Future of 6 Undergraduate Education OPENING Ron Pressman, CEO, Institutional Financial Services, TIAA Joseph E. Aoun, 7th President, Northeastern University; Author, Robot-Proof: Higher Education in the Age of Artificial Intelligence COMMENTS John D. Simon, 14th President, Lehigh University Valerie Smith, 15th President, Swarthmore College Joanne Berger-Sweeney, 22nd President, Trinity College Kimberly W. Benston, President, Haverford College David A. Greene, 20th President, Colby College David A. Thomas, 12th President, Morehouse College Jake B. Schrum, 21st President, Emory & Henry College John J. Petillo, President, Sacred Heart University Phyllis Worthy Dawkins, 18th President, Bennett College Roslyn Clark Artis, 14th President, Benedict College RESPONSES Robert S. Murley, Chairman, Educational Testing Service Richard D. Legon, President, Association of Governing Boards of Colleges & Universities Michael K. Thomas, President & CEO, New England Board of Higher Education Meredith Rosenberg, Practice Leader–Digital Education, Russell Reynolds Associates Political Axes and Punitive Taxes: Funding, Support, and Public Trust 8 OPENING John A. Perez, 68th Speaker, California Assembly; Board of Regents, UC System John B. King Jr., 10th U.S. Secretary of Education; President & CEO, The Education Trust Donna E. Shalala, 18th U.S. Secretary of Health Human Services; President, University of Miami (2001- 2015) COMMENTS Mark P. Becker, 7th President, Georgia State University Raynard S. -

Throughout Her Extraordinary Life, Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole Has Not Only

ThroughoutJUMPING her extraordinary life, Dr. JohnnettaAT B.THE Cole has not onlySUN reached for the sun but has shone that light on others BY JACKIE KRENTZMAN African Art, she has dedicated her life to bringing others—especially “Life’s most persistent those from marginalized communities—out of the shadows. and urgent question is, Her family may have been affluent, but that provided little buffer living in the Deep South in the Jim Crow era. “I didn’t have to go ‘what are you doing to the back of the bus,” she says. “I was always driven around in a for others?’” private car. But when I got out of that car, or even while in it, I ran — Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. into the horrific expressions of racial discrimination around me.” Her family, she says, distilled in her a set of bedrock values. r. Johnnetta B. Cole, the director of the Smith- One of those values, although it didn’t have a name at the time, sonian National Museum of African Art, grew was gender equity, which played out in ways large and small. Her up in a prosperous African American family in mother was a college professor—and her father was a better cook Jacksonville, Florida. Her great-grandfather than her mother. It was her father, not her mother or her sister, was the state’s first black millionaire. Her fa- who would braid her hair. “He was gentler,” explains Cole. ther was a successful insurance executive and Cole considers her parents and her great-grandfather Abraham her mother an English professor at a nearby Lincoln Lewis her role models. -

The Ebony Seven: a Presidential Blueprint for Private Black College Achievement of Global Competitiveness

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 The bE ony Seven: A Presidential Blueprint for Private Black College Achievement of Global Competitiveness Walter T. Tillman Jr. Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Tillman Jr., Walter T., "The bonE y Seven: A Presidential Blueprint for Private Black College Achievement of Global Competitiveness" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2557. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2557 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE EBONY SEVEN: A PRESIDENTIAL BLUEPRINT FOR PRIVATE BLACK COLLEGE ACHIEVEMENT OF GLOBAL COMPETITIVENESS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Education by Walter T. Tillman, Jr. B.A., Dillard University, 1998 M.Ed., University of New Orleans, 2001 December 2014 ©2014 Walter T. Tillman, Jr. All rights reserved. ii This dissertation is dedicated to the three individuals whose impact on my life made me the man that I am today and the leader and scholar I aspire to be – my late parents, Josephine and Walter T. Tillman, Sr. and my late babysitter Murt Marshall. Momma: for doing all you knew to do and giving all you had or could find for my siblings and me to have exponential opportunities, I dedicate this work. -

2014 Annual Report

CHANGING THE ATMOSPHERE 2014 ANNUAL REPORT Advancing Knowledge, Solving Human Problems EXECUTIVE BOARD AND COMMITTEES AAA 2014 Practicing/ AAA Treasurer-Ex Officio Committee on Ethics Executive Board Professional Seat Edmund T Hamann Pamela Stone Elizabeth Briody (2013–16) (2012–15) President Cultural Keys LLC University of Nebraska, Committee for Monica Heller (2013–15) Lincoln Human Rights University of Toronto, Student Seat Eric Johnson Ontario Institute for Studies Karen G Williams (2012–15) AAA Committees In Education The Graduate Center of the and Chairs Committee on Minority City University of New York Issues in Anthropology President-Elect/Vice Annual Meeting Shalini Shankar President Undesignated #1 Executive Program Alisse Waterston (2013–15) Cheryl Mwaria (2012–15) Committee Committee on Gender John Jay College of the City Hofstra University Mary Gray Equity in Anthropology University of New York Rachel Watkins Rebecca Galemba Undesignated #2 Secretary Mark Aldenderfer (2013–16) Audit Committee Committee on Practicing Margaret Buckner (2012–15) University of California, Cheryl Mwaria Applied and Public Missouri State University Merced Interest Anthropology Awards Committee Mary Butler Archaeology Seat Undesignated #3 Bernard Perley Sandra Lopez Varella Fran Mascia-Lees (2011–14) Committee on (2011–14) Rutgers University Association Operations Labor Relations Facultad de Filosofia Committee y Letras, Universidad Christine Walley Undesignated #4 Karen Nakamura NacionalAutonoma Rayna Rapp de Mexico Committee on (2012–15) Anthropological -

The Politics of Success: an HBCU Leadership Paradigm

THE POLITICS OF SUCCESS : AN HBCU LEADERSHI P PARADIGM A Monograph by Barbara R. Hatton for “Documenting the Perspectives of Past HBCU Presidents” An Oral History Project Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library THE POLITICS OF SUCCESS : AN HBCU LEADERSHI P PARADIGM Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library © 2012 Robert W. Woodruff Library of the Atlanta University Center, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical including photocopying and recording, or by any storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publisher, Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library 111 James P. Brawley Drive SW Atlanta, GA 30314. Cover and Layout Design: Charles Lowder Printing: BCP Digital Printing THE POLITICS OF SUCCESS : An HBCU LEADERSHI P PARADIGM A Monograph by Barbara R. Hatton for “Documenting the Perspectives of Past HBCU Presidents” Loretta Parham, Project Director Karen Jefferson, Project Coordinator & Editor An Oral History Project of the Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library In Collaboration with the HBCU With Funding from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation November 2012 Table Of Contents PREFACE 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 6 PROLOGUE The HBCU Leadership Paradigm: Facing the Odds 7 The HBCU Leadership Legacy: Overcoming the Odds 11 RETROSPECTIVES OF PAST PRESIDENTS 20 Exemplars and Mentors Of HBCU Presidents 21 Leadership In Public HBCUs 24 Leadership In Private HBCUs 32 EPILOGUE 38 REFERENCES 40 HBCU Leadership Photo Gallery 43 APPENDICES I. Selected Quotes From The Interviews 56 II. The Council Of Past HBCU Presidents, 2011-2012 108 III. -

Skeletal Biology Final Report: the New York

THE NEW YORK AFRICAN BURIAL GROUND SKELETAL BIOLOGY FINAL REPORT VOLUME I Section I: Background of the New York African Burial Ground Project Section II: Origins and Arrival of Africans in Colonial New York Section III: Life and Death in Colonial New York Edited by Michael L. Blakey and Lesley M. Rankin-Hill THE AFRICAN BURIAL GROUND PROJECT HOWARD UNIVERSITY WASHINGTON, DC FOR THE UNITED STATES GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION NORTHEASTERN AND CARIBBEAN REGION December 2004 Howard University’s New York African Burial Ground Project was funded by the U.S. General Services Administration Under Contract No. GS-02P-93-CUC-0071 ╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬ Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the editor(s) and/or the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. General Services Administration or Howard University. ii Table of Contents List of Tables v List of Figures ix Contributors to the Skeletal Biology Component, The African Burial Ground xv Project Acknowledgements xviii Section I: Background of the New York African Burial Ground Project 1 Introduction 2 (M.L. Blakey) 2 History and Comparison of Bioarchaeological Studies in the African 38 Diaspora (M.L. Blakey) 3 Theory: An Ethical Epistemology of Publicly Engaged Biocultural 98 Research (M.L. Blakey) 4 Laboratory Organization, Methods, and Processes 116 (M.L. Blakey, M.E. Mack, K. Shujaa, and R. Watkins) Section II: Origins and Arrival of Africans in Colonial New York 5 Origins of the New York African Burial Ground Population: Biological 150 Evidence of Lineage and Population Affiliation using Genetics, Craniometrics, and Dental Morphology (F.L.C. -

Johnnetta B. Cole, Educator and Humanitarian to Headline Two Dr

University of Dayton eCommons News Releases Marketing and Communications 12-18-2006 Johnnetta B. Cole, Educator and Humanitarian to Headline Two Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Events Jan. 15-16 Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/news_rls Recommended Citation "Johnnetta B. Cole, Educator and Humanitarian to Headline Two Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Events Jan. 15-16" (2006). News Releases. 9501. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/news_rls/9501 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marketing and Communications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in News Releases by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. IJ"A(I) Dec. 18, 2006 UNIVERSITY o Contact: Teri Rizvi [email protected] 93 7-229-3241 DAYTON NEWS RELEASE (Editor's Note: To request a photo, contact Teri Rizvi at 937-229-3241. Johnnetta B. Cole will be available to meet with the media at 6:15 p.m. on Monday, Tan. 15, at the Mandalay Banquet Center.) JOHNNETIA B. COLE, EDUCATOR AND HUMANITARIAN, TO HEADLINE TWO DR. MARTIN .LUTHER KING JR. EVENTS JAN. 15-16 DAYTON, Ohio - Johnnetta Betsch Cole, a human rights champion and the only person to ever preside over two historically black colleges for women, will headline two community events honoring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s legacy Jan. 15-16. Cole will address "How Must We Honor the Life and Work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.?" at 6:30p.m., Monday, Jan. 15, at the Dr.