African-American Leaders in the Field of Science: a Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Washington Carver

George Washington LEVELED BOOK • O Carver A Reading A–Z Level O Leveled Book Word Count: 646 George Washington • R Carver L • O Written by Cynthia Kennedy Henzel Visit www.readinga-z.com www.readinga-z.com for thousands of books and materials. Photo Credits: Front cover: © Corbis; back cover, pages 6, 9: © The Granger Collection, NYC; title page: © Christopher Gannon/Tribune/AP Images; pages 3, 11: © AP Images; page 5 (top): courtesy of George Washington Carver National Monument; page George Washington 5 (bottom): courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [HABS MO,73-DIA.V,1--1]; pages 10, 15: © Bettmann/Corbis; page 12: © Tetra Images/ Carver Alamy; page 14: © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis George Washington Carver Written by Cynthia Kennedy Henzel Level O Leveled Book © Learning A–Z Correlation Written by Cynthia Kennedy Henzel LEVEL O Illustrated by Stephen Marchesi Fountas & Pinnell M All rights reserved. Reading Recovery 20 DRA 28 www.readinga-z.com www.readinga-z.com States Where Carver Lived and Worked Iowa Nebraska Indiana Ohio Illinois Kansas Missouri Kentucky Tennessee Oklahoma Arkansas Mississippi Georgia Alabama Texas Louisiana Florida Carver grew up in Missouri, studied in Kansas and Iowa, and worked in Alabama. Born a Slave George Washington Carver in the lab, 1940 George Washington Carver was born in Table of Contents Missouri in 1864, during the Civil War. Born a Slave ............................................... 4 The Civil War (1861–1865) The Civil War was a fight between two sides of the Learning on His Own .............................. 6 United States, the North and the South. When it began, slavery was legal in fifteen “slave states” in the South and Making a Difference ................................ -

Roger Arliner Young (RAY) Clean Energy Fellowship

Roger Arliner Young (RAY) Errol Mazursky (he/him) Clean Energy Fellowship 2020 Cycle Informational Webinar Webinar Agenda • Story of RAY • RAY Fellows Benefits • Program Structure • RAY Host Organization Benefits • RAY Supervisor Role + Benefits • Program Fee Structure • RAY Timeline + Opportunities to be involved • Q&A Story of RAY: Green 2.0 More info: https://www.diversegreen.org/beyond-diversity/ Story of RAY: “Changing the Face” of Marine Conservation & Advocacy Story of RAY: The Person • Dr. Roger Arliner Young (1889 – November 9, 1964) o American Scientist of zoology, biology, and marine biology o First black woman to receive a doctorate degree in zoology o First black woman to conduct and publish research in her field o BS from Howard University / MS in Zoology from University of Chicago / PhD in Zoology from University of Pennsylvania o Recognized in a 2005 Congressional Resolution celebrating accomplishments of those “who have broken through many barriers to achieve greatness in science” o Learn more about Dr. Young: https://oceanconservancy.org/blog/2017/11/29/little-known-lif e-first-african-american-female-zoologist/ Story of RAY: Our Purpose • The purpose of the RAY Clean Energy Diversity Fellowship Program is to: o Build career pathways into clean energy for recent college graduates of color o Equip Fellows with tools and support to grow and serve as clean energy leaders o Promote inclusivity and culture shifts at clean energy and advocacy organizations Story of RAY: Developing the Clean Energy Fellowship Story of RAY: Our Fellow -

African American History & Culture

IN September 2016 BLACK AMERICAsmithsonian.com Smithsonian WITH CONTRIBUTIONS FROM: REP. JOHN LEWIS BLACK TWITTER OPRAH WINFREY A WORLD IN SPIKE LEE CRISIS FINDS ANGELA Y. DAVIS ITS VOICE ISABEL WILKERSON LONNIE G. BUNCH III HEADING NATASHA TRETHEWEY NORTH BERNICE KING THE GREAT ANDREW YOUNG MIGRATION TOURÉ JESMYN WARD CHANGED WENDEL A. WHITE EVERYTHING ILYASAH SHABAZZ MAE JEMISON ESCAPE FROM SHEILA E. BONDAGE JACQUELINE WOODSON A LONG-LOST CHARLES JOHNSON SETTLEMENT JENNA WORTHAM OF RUNAWAY DEBORAH WILLIS SLAVES THOMAS CHATTERTON WILLIAMS SINGING and many more THE BLUES THE SALVATION DEFINING MOMENT OF AMERICA’S ROOTS MUSIC THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY & CULTURE OPENS IN WASHINGTON, D.C. SMITHSONIAN.COM SPECIAL�ADVERTISING�SECTION�|�Discover Washington, DC FAMILY GETAWAY TO DC FALL�EVENTS� From outdoor activities to free museums, your AT&T�NATION’S�FOOTBALL� nation’s capital has never looked so cool! CLASSIC�® Sept. 17 Celebrate the passion and tradition of IN�THE� the college football experience as the Howard University Bisons take on the NEIGHBORHOOD Hampton University Pirates. THE�NATIONAL�MALL NATIONAL�MUSEUM�OF� Take a Big Bus Tour around the National AFRICAN�AMERICAN�HISTORY�&� Mall to visit iconic sites including the CULTURE�GRAND�OPENING Washington Monument. Or, explore Sept. 24 on your own to find your own favorite History will be made with the debut of monument; the Martin Luther King, Jr., the National Mall’s newest Smithsonian Lincoln and World War II memorials Ford’s Th eatre in museum, dedicated to the African are great options. American experience. Penn Quarter NATIONAL�BOOK�FESTIVAL� CAPITOL�RIVERFRONT Sept. -

Famous African Americans

African American Leaders African American Leaders Martin Luther King Jr. was an African American leader who lived from 1929 to 1968. He worked to help people be treated fairly and equally. We remember him with a national holiday. Look inside to learn about other African Americans who have made a difference in the history of the United States. Lyndon B. Johnson Library Rev. Martin Luther King Famous African Americans Look at our scrapbook of some African American leaders who have changed history. Rosa Parks fought for civil rights for African Americans. Civil rights make sure people are treated equally under the law. In 1955, she was arrested in Alabama for not giving up her bus seat to a white man. ReadWorks.org Copyright © 2006 Weekly Reader Corporation. All rights reserved. Used by permission.Weekly Reader is a registered trademark of Weekly Reader Corporation. African American Leaders Jackie Robinson batted his way into history. In 1947, he became the first African American to play major-league baseball. Condoleezza Library of Congress Rice is the first Jackie Robinson African American woman to be the U.S. Secretary of State. In this important job, she helps the President work with the governments of other countries. World Almanac for Kids Condoleezza Rice George Washington Carver was a famous inventor who found more than 300 uses for peanuts. He discovered that peanuts could be used to make soap, glue, and paint. A Special Speech In 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous "I Have a Dream" speech. He spoke in Washington, D.C., in front ReadWorks.org Copyright © 2006 Weekly Reader Corporation. -

Racial Literacy Curriculum Parent/Guardian Companion Guide

Pollyanna Racial Literacy Curriculum PARENT/GUARDIAN COMPANION GUIDE ©2019 Pollyanna, Inc. – Parent/Guardian Companion Guide | Monique Vogelsang, Primary Contributor CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Why is important to learn about and discuss race? 1 What is the Racial Literacy Curriculum? 1 How is the Curriculum Structured? 2 What is the Parent/Guardian Companion Guide? 2 How is the Companion Guide Structured? 3 Quick Notes About Terminology 3 UNITS The Physical World Around Us 5 A Celebration of (Skin) Colors We Are Part of a Larger Community 9 Encouraging Kindness, Social Awareness, and Empathy Diversity Around the World 13 How Geography and Our Daily Lives Connect Us Stories of Activism 17 How One Voice Can Change a Community (and Bridge the World) The Development of Civilization 24 How Geography Gave Some Populations a Head Start (Dispelling Myths of Racial Superiority) How “Immigration” Shaped the Racial and 29 Cultural Landscape of the United States The Persecution, Resistance, and Contributions of Immigrants and Enslaved People The Historical Construction of Race and 36 Current Racial Identities Throughout U.S. Society The Danger of a Single Story What is Race? 48 How Science, Society, and the Media (Mis)represent Race Please note: This document is strictly private, confidential Race as Primary “Institution” of the U.S. 55 and should not be copied, distributed or reproduced in How We May Combat Systemic Inequality whole or in part, nor passed to any third party outside of your school’s parents/guardians, without the prior consent of Pollyanna. PAGE ii ©2019 Pollyanna, Inc. – Parent/Guardian Companion Guide | Monique Vogelsang, Primary Contributor INTRODUCTION Why is it important to learn about and discuss race? Educators, sociologists, and psychologists recommend that we address concepts of race and racism with our children as soon as possible. -

Navigating Crucial Conversation for Chapters

Welcome! We are please to present to you one of the Sigma Leadership Academy’s first Signature Program – Navigating Crucial Conversations. This training session, was developed in partnership with Phillip Edge, Faculty Member of the Academy. The main goal of this session is to assist our members with their achievement for greater success in the workplace and Fraternity life through meaningful development. Two hours does not lend itself to addressing all skills necessary for personal and professional success. This session is interactive and insightful for Sigmas and other participants alike. We hope you find this training a powerful and valuable tool in advancing your skills. Our expectations for today’s session are for you to engage fully‐using your head and your heart. Secondly, we expect you to provide candid feedback on today’s session and provide recommendations for future sessions. On behalf of the Faculty and Staff of the Sigma Leadership Academy, Thank you! Enjoy the Session! John E. White Academy’s Director Empowering Regional Directors through Effective Communications‐ –Navigating Crucial Conversations -1- Empowering Regional Directors through Effective Communications –Navigating Crucial Conversations A Sigma Leadership Academy Signature Learning Lab Learning how to create and communicate in an atmosphere where you and others feel safe giving and receiving constructive feedback is important skill for leaders today. During this learning lab we will introduce ways to navigate potentially damaging curial conversations and scenarios. We will learn how written and unwritten rules in the workplace impacts career growth. We will introduce ways to seal allies and solutions that enable you to remove potential restraints that impede the growth of our Fraternity. -

African American Scientists

AFRICAN AMERICAN SCIENTISTS Benjamin Banneker Born into a family of free blacks in Maryland, Banneker learned the rudiments of (1731-1806) reading, writing, and arithmetic from his grandmother and a Quaker schoolmaster. Later he taught himself advanced mathematics and astronomy. He is best known for publishing an almanac based on his astronomical calculations. Rebecca Cole Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Cole was the second black woman to graduate (1846-1922) from medical school (1867). She joined Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, the first white woman physician, in New York and taught hygiene and childcare to families in poor neighborhoods. Edward Alexander Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Bouchet was the first African American to Bouchet graduate (1874) from Yale College. In 1876, upon receiving his Ph.D. in physics (1852-1918) from Yale, he became the first African American to earn a doctorate. Bouchet spent his career teaching college chemistry and physics. Dr. Daniel Hale Williams was born in Pennsylvania and attended medical school in Chicago, where Williams he received his M.D. in 1883. He founded the Provident Hospital in Chicago in 1891, (1856-1931) and he performed the first successful open heart surgery in 1893. George Washington Born into slavery in Missouri, Carver later earned degrees from Iowa Agricultural Carver College. The director of agricultural research at the Tuskegee Institute from 1896 (1865?-1943) until his death, Carver developed hundreds of applications for farm products important to the economy of the South, including the peanut, sweet potato, soybean, and pecan. Charles Henry Turner A native of Cincinnati, Ohio, Turner received a B.S. -

Ledroit Park Historic Walking Tour Written by Eric Fidler, September 2016

LeDroit Park Historic Walking Tour Written by Eric Fidler, September 2016 Introduction • Howard University established in 1867 by Oliver Otis Howard o Civil War General o Commissioner of the Freedman’s Bureau (1865-74) § Reconstruction agency concerned with welfare of freed slaves § Andrew Johnson wasn’t sympathetic o President of HU (1869-74) o HU short on cash • LeDroit Park founded in 1873 by Amzi Lorenzo Barber and his brother-in-law Andrew Langdon. o Barber on the Board of Trustees of Howard Univ. o Named neighborhood for his father-in-law, LeDroict Langdon, a real estate broker o Barber went on to develop part of Columbia Heights o Barber later moved to New York, started the Locomobile car company, became the “asphalt king” of New York. Show image S • LeDroit Park built as a “romantic” suburb of Washington, with houses on spacious green lots • Architect: James McGill o Inspired by Andrew Jackson Downing’s “Architecture of Country Houses” o Idyllic theory of architecture: living in the idyllic settings would make residents more virtuous • Streets named for trees, e.g. Maple (T), Juniper (6th), Larch (5th), etc. • Built as exclusively white neighborhood in the 1870s, but from 1900 to 1910 became almost exclusively black, home of Washington’s black intelligentsia--- poets, lawyers, civil rights activists, a mayor, a Senator, doctors, professors. o stamps, the U.S. passport, two Supreme Court cases on civil rights • Fence war 1880s • Relationship to Howard Theatre 531 T Street – Originally build as a duplex, now a condo. Style: Italianate (low hipped roof, deep projecting cornice, ornate wood brackets) Show image B 525 T Street – Howard Theatre performers stayed here. -

Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions Revised September 13, 2018 B C D 1 CATEGORY QUESTION ANSWER

Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions Revised September 13, 2018 B C D 1 CATEGORY QUESTION ANSWER What national organization was founded on President National Association for the Arts Advancement of Colored People (or Lincoln’s Birthday? NAACP) 2 In 1905 the first black symphony was founded. What Sports Philadelphia Concert Orchestra was it called? 3 The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in what Sports 1852 4 year? Entertainment In what state is Tuskegee Institute located? Alabama 5 Who was the first Black American inducted into the Pro Business & Education Emlen Tunnell 6 Football Hall of Fame? In 1986, Dexter Gordan was nominated for an Oscar for History Round Midnight 7 his performance in what film? During the first two-thirds of the seventeenth century Science & Exploration Holland and Portugal what two countries dominated the African slave trade? 8 In 1994, which president named Eddie Jordan, Jr. as the Business & Education first African American to hold the post of U.S. Attorney President Bill Clinton 9 in the state of Louisiana? Frank Robinson became the first Black American Arts Cleveland Indians 10 manager in major league baseball for what team? What company has a successful series of television Politics & Military commercials that started in 1974 and features Bill Jell-O 11 Cosby? He worked for the NAACP and became the first field Entertainment secretary in Jackson, Mississippi. He was shot in June Medgar Evers 12 1963. Who was he? Performing in evening attire, these stars of The Creole Entertainment Show were the first African American couple to perform Charles Johnson and Dora Dean 13 on Broadway. -

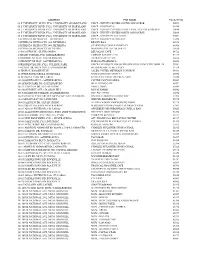

FSE Permit Numbers by Address

ADDRESS FSE NAME FACILITY ID 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER SOUTH CONCOURSE 50891 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - FOOTNOTES 55245 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER EVENT LEVEL STANDS & PRESS P 50888 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER NORTH CONCOURSE 50890 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY PLAZA LEVEL 50892 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, -, BETHESDA HYATT REGENCY BETHESDA 53242 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, 000, BETHESDA BROWN BAG 66933 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, 000, BETHESDA STARBUCKS COFFEE COMPANY 66506 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, BETHESDA MORTON'S THE STEAK HOUSE 50528 1 DISCOVERY PL, SILVER SPRING DELGADOS CAFÉ 64722 1 GRAND CORNER AVE, GAITHERSBURG CORNER BAKERY #120 52127 1 MEDIMMUNE WAY, GAITHERSBURG ASTRAZENECA CAFÉ 66652 1 MEDIMMUNE WAY, GAITHERSBURG FLIK@ASTRAZENECA 66653 1 PRESIDENTIAL DR, FY21, COLLEGE PARK UMCP-UNIVERSITY HOUSE PRESIDENT'S EVENT CTR COMPLEX 57082 1 SCHOOL DR, MCPS COV, GAITHERSBURG FIELDS ROAD ELEMENTARY 54538 10 HIGH ST, BROOKEVILLE SALEM UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 54491 10 UPPER ROCK CIRCLE, ROCKVILLE MOM'S ORGANIC MARKET 65996 10 WATKINS PARK DR, LARGO KENTUCKY FRIED CHICKEN #5296 50348 100 BOARDWALK PL, GAITHERSBURG COPPER CANYON GRILL 55889 100 EDISON PARK DR, GAITHERSBURG WELL BEING CAFÉ 64892 100 LEXINGTON DR, SILVER SPRING SWEET FROG 65889 100 MONUMENT AVE, CD, OXON HILL ROYAL FARMS 66642 100 PARAMOUNT PARK DR, GAITHERSBURG HOT POT HERO 66974 100 TSCHIFFELY -

Black History, 1877-1954

THE BRITISH LIBRARY AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY AND LIFE: 1877-1954 A SELECTIVE GUIDE TO MATERIALS IN THE BRITISH LIBRARY BY JEAN KEMBLE THE ECCLES CENTRE FOR AMERICAN STUDIES AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY AND LIFE, 1877-1954 Contents Introduction Agriculture Art & Photography Civil Rights Crime and Punishment Demography Du Bois, W.E.B. Economics Education Entertainment – Film, Radio, Theatre Family Folklore Freemasonry Marcus Garvey General Great Depression/New Deal Great Migration Health & Medicine Historiography Ku Klux Klan Law Leadership Libraries Lynching & Violence Military NAACP National Urban League Philanthropy Politics Press Race Relations & ‘The Negro Question’ Religion Riots & Protests Sport Transport Tuskegee Institute Urban Life Booker T. Washington West Women Work & Unions World Wars States Alabama Arkansas California Colorado Connecticut District of Columbia Florida Georgia Illinois Indiana Kansas Kentucky Louisiana Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Mississippi Missouri Nebraska Nevada New Jersey New York North Carolina Ohio Oklahoma Oregon Pennsylvania South Carolina Tennessee Texas Virginia Washington West Virginia Wisconsin Wyoming Bibliographies/Reference works Introduction Since the civil rights movement of the 1960s, African American history, once the preserve of a few dedicated individuals, has experienced an expansion unprecedented in historical research. The effect of this on-going, scholarly ‘explosion’, in which both black and white historians are actively engaged, is both manifold and wide-reaching for in illuminating myriad aspects of African American life and culture from the colonial period to the very recent past it is simultaneously, and inevitably, enriching our understanding of the entire fabric of American social, economic, cultural and political history. Perhaps not surprisingly the depth and breadth of coverage received by particular topics and time-periods has so far been uneven. -

Knowing Doing

KNOWING OING &D. C S L EWI S I N S TITUTE PROFILE IN FAITH George Washington Carver (1860-1943): “… the greatest of these is love” (1 Corinthians 13:13) by David B. Calhoun, Ph.D. Professor Emeritus of Church History Covenant Theological Seminary, St. Louis, Missouri This article originally appeared in the Summer 2013 issue of Knowing & Doing. Missouri Kansas n the southwestern corner of the troubled bor- Seeking more schooling and der state of Missouri, Moses Carver and his wife, a livelihood, George wandered ISusan, farmed 240 acres near the tiny settlement through the state of Kansas, tak- of Diamond Grove. They owned slaves, including ing classes and working in vari- a young woman named Mary who had at least two ous jobs. He opened a laundry sons, the youngest named George. When George was in one town and made enough an infant, probably in 1864, he and his mother were money to buy some real estate, stolen away and resold in a neighboring state. Mary which he sold for a profit. He David B. Calhoun, Ph.D. was never seen again, but George, small and frail, was went to business school and worked as a stenographer. found. Mr. Carver paid for the baby’s return, giving He was accepted at Highland College, in northeastern up his finest horse. Kansas, but when he arrived and administrators saw The Carvers cared for George, and he stayed with his race, they refused him admittance. As he did in all them after the war. George was bright and eager to the disappointments of his life, he “trusted God and learn.