[2015] NZHC 43 UNDER the Judicature Amendment Act 1972 An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kapiti Coast District / [email protected] / P

APRIL 2019 KAPITI COAST DISTRICT WWW.INTEREST.CO.NZ / [email protected] / P. 09 3609670 KAPITI COAST DISTRICT HOME LOAN AFFORDABILITY REPORT April 2019 Home loan affordability is a measure of the proportion of take-home pay that is needed to make the mortgage payment for a typical household. If that is less than 40%, then a mortgage is considered ‘affordable’. The following are typical assessments for households at three stages of home ownership. FIRST HOME BUYERS 25-29 YOUNG FAMILY 30-34 OLDER FAMILY 35-39 First home buyers earn a medi- Young family buyers earn medi- Older family buyers earn medi- an income for their age group, an incomes in their age bracket, an incomes in their age brack- and buy a first quartile house and buy a median house in et, and buy a median house in in their area. Both parties work their area. One partner works their area. Both partners work full-time. half-time. full-time. Mortgage payment as a Mortgage payment as a Mortgage payment as a percentage of the take home pay percentage of the take home pay percentage of the take home pay Take Home April 19 29.7% Take Home April 19 29.2% Take Home Pay Pay Pay April 19 17.6% April 18 30.3% April 18 26.8% $1,517.11 $1,334.99 $1,856.59 April 18 17.1% per Week April 17 26.9% per Week April 17 29.2% per Week April 17 19.4% April 14 - April 14 26.0% April 14 33.3% This report estimates how affordable it would be for a couple This report estimates how affordable it would be for a couple This report estimates how affordable it would be for a couple where both are aged 25–29 and are working full time, to buy a with a young family to move up the property ladder and buy their who are both aged 35-39 and working full time, to move up the home at the lower quartile price in Kapiti Coast District. -

Making a Community: Filipinos in Wellington

Making a Community: Filipinos in Wellington September 2017 ISBN 978-0-9941409-4-4 (PDF) Making a Community: Filipinos in Wellington About the Author As an American living in New Zealand, I’ve been observing the debate here on immigration and multiculturalism. I arrived in Wellington last year with my Kiwi husband and three-year old son – and while settling in we’ve spent a lot of time discovering the delights of the city and its people. The experience also gave me some perspective on being a migrant far from home. I have a professional interest in South East Asian history, languages and culture - I just completed a PhD on the subject. I speak some Filipino, and am fascinated by the Philippines’ complex history. One of the major phenomena in the Philippines since the 1970s has been the growth of the global Filipino diaspora. That story has often been full of sadness. So I was intrigued by anecdotes of positivity and success from Wellington. Writing about how the migrant Filipino community has settled in New Zealand has been more than just a research project. It has highlighted how migration plays a role in community building. It also has meaning for me and my family’s future here. I really wanted to share some of the stories that I think reflect successful outcomes from immigration over the past thirty years. By Dr Rebecca Townsend 1 Key Points 1. 2. 3. Filipinos comprise 1 percent of Filipinos are a vital part of Most Filipinos in New Zealand are New Zealand’s population – the New Zealand’s dairy, healthcare, not Overseas Filipino Workers third largest Asian ethnic group construction, nursing, aged care, (OFW). -

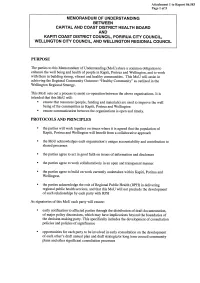

Memorandum of Understanding Between

Attachment 1 to Report 06.583 Page 1 of 5 MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING BETWEEN CAPITAL AND COAST DISTRICT HEALTH BOARD AND KAPITI COAST DISTRICT COUNCIL, PORIRUA CITY COUNCIL, WELLINGTON CITY COUNCIL, AND WELLINGTON REGIONAL COUNCIL PURPOSE The parties to this Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) share a common obligation to enhance the well being and health of people in Kapiti, Porirua and Wellington, and to work with them in building strong, vibrant and healthy communities. This MoU will assist in achieving the Regional Community Outcome: "Healthy Community" as outlined in the Wellington Regional Strategy. This MoU sets out a process to assist co-operation between the above organisations. It is intended that this MoU will: • ensure that resources (people, funding and materials) are used to improve the well being of the communities in Kapiti, Porirua and Wellington • ensure communication between the organisations is open and timely. PROTOCOLS AND PRINCIPLES • the parties will work together on issues where it is agreed that the population of Kapiti, Porirua and Wellington will benefit from a collaborative approach • the MoU acknowledges each organisation's unique accountability and contribution to shared processes • the parties agree to act in good faith on issues of information and disclosure • the parties agree to work collaboratively in an open and transparent manner • the parties agree to build on work currently undertaken within Kapiti, Porirua and Wellington. • the parties acknowledge the role of Regional Public Health (RPH) in delivering regional public health services, and that this MoU will not preclude the development of such relationships by each party with RPH As signatories of this MoU each party will ensure: • early notification to affected parties through the distribution of draft documentation, of major policy discussions, which may have implications beyond the boundaries of the decision-making party. -

Kapiti Coast District Council and Other Councils, Including Population Forecasts

Housing and Business Development Capacity Assessment Kāpiti Coast District Council November 2019 Housing and Business Land Capacity Assessment 229 230 Housing and Business Land Capacity Assessment Contents Executive Summary 232 5.0 Infrastructure 270 Background 233 5.1 Three Waters 270 Residential demand 233 5.2 Local Road Network 271 Residential capacity 233 5.3 State Highway Network 272 Business demand 234 5.4 Public Transport 272 Business capacity 234 5.5 Open Space 273 Infrastructure capacity 234 5.6 Education 273 1.0 Introduction 237 6.0 Relationship between Housing and Business Land 274 2.0 Existing Policy Context 238 7.0 Monitoring 275 2.1 Kāpiti Coast District Plan 238 7.1 Historic Development Activity 275 2.2 Development Management Strategy 2007 238 7.2 Market Indicators 278 2.3 Infrastructure Strategy 2018-2048 238 7.3 Price Efficiency Indicators 285 2.4 Roads of National Significance and Town Centres Transformation 239 8.0 Conclusion 293 3.0 Residential Demand and Capacity 240 9.0 Next Actions 294 3.1 Historic urban growth and settlement 240 3.2 Current growth and settlement trends 240 3.3 Future Housing Demand 241 3.4 Housing Development Capacity 248 3.5 Housing Feasibility, Realisation and Sufficiency 251 4.0 Business Demand and Capacity 258 4.1 Business Development Context 258 4.2 Current Economic and Business Drivers 259 4.3 Future Business Demand 260 4.4 Business Development Capacity 264 4.5 Business Feasibility, Realisation and Sufficiency 266 Housing and Business Land Capacity Assessment 231 Executive Summary This report presents the results from the Wellington Region Housing and Business Development Capacity Assessment (HBA) for the Kāpiti Coast District Council. -

The Case of Kapiti Coast District Council

THE NEW ZEALAND MEDICAL JOURNAL Journal of the New Zealand Medical Association Getting an outdoor smokefree policy: the case of Kapiti Coast District Council Leigh Halkett, George Thomson Abstract Aim To explore how a smokefree parks policy was conceived, accepted and developed by and for Kapiti Coast District Council (KCDC). Method Thirteen people involved in the smokefree parks policy process for KCDC were interviewed in person during November–December 2008. Supporting documentation and websites were accessed and reviewed. Results In September 2008 the KCDC agreed to adopt a smokefree parks and playground policy, following an initiative from a smokefree coalition of several public health organisations. The policy was developed collaboratively by this coalition with input from the council, and was supported by key local organisations. The KCDC appears to have adopted a smokefree outdoor areas (SFOA) policy because of demonstrated public support, the relative simplicity and low cost of the policy, the success of similar policies elsewhere, and because of the alignment with desired community outcomes. The challenges included finding funding and allocating staff time for this project. There were also concerns with how the policy would be enforced. Conclusions A collaborative approach amongst health and community groups for achieving SFOA policies works well. The experience with council SFOA policies has considerable impact on the adoption of similar policies by other councils. To maximise this influence, information about the policies needs to be spread nationally by the health and local government sectors. Legislative efforts to reduce smoking and the exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS) in New Zealand have included the Smoke-free Environments Act 1990 (SEA) and the Smoke-free Environments Amendment Act 2003 (SEAA). -

Part C.10 Landscapes for List of Outstanding Landscapes and the Planning Maps)

APPENDIX 3 Operative Kāpiti Coast District Plan Objectives and Policies Proposed Kāpiti Coast District Plan Objectives and Policies S149(G)3 Key Issues Report – Kāpiti Coast District Council C.1: RESIDENTIAL ZONE C.1 RESIDENTIAL ZONE Over 90% of the district's population live on less than 4% of the land. This land comprises the residential environment. To accommodate this population there has been considerable investment made in buildings, services (water, gas, wastewater disposal) roading and amenity facilities (shops and schools). This represents a significant physical resource which needs to be managed to enable people and communities to meet their needs and to minimise any adverse effects of activities on both the natural and physical environment. The management of this resource can be achieved within the District Plan through controls in the design of subdivision, use and development. The objectives and policies set out below in C.1.1 are intended to address the significant resource management issues identified in B.2. The related subdivision and development issues in B.8 are addressed in C.7. C.1.1 Objectives & Policies OBJECTIVE 1.0 - GENERAL ENSURE THAT THE LOW DENSITY, QUIET CHARACTER OF THE DISTRICT’S RESIDENTIAL ENVIRONMENTS IS MAINTAINED AND THAT ADVERSE EFFECTS ON THE AMENITY VALUES THAT CONSTITUTE THIS CHARACTER AND MAKE THE RESIDENTIAL ENVIRONMENTS SAFE, PLEASANT AND HEALTHY PLACES FOR RESIDENTS ARE AVOIDED, REMEDIED OR MITIGATED. The residential environments within the Kapiti Coast District generally have a low density character, typified by low building heights and density and a high proportion of public and private open space. -

EPA Board of Enquiry Hon Sir John Hanley David Bunting, Environment

EPA Board of Enquiry Hon Sir John Hanley David Bunting, Environment Commissioner Glenice Paine Mark Appledoorn Intro My name is Ruben Blok and I live at 79 Belvedere Ave, Waikanae. I am a Business Intelligence consultant with a private local firm and I create analytic reporting solutions for major private and public sector organisations throughout the Australasia. I am usually not too worried about government decisions but given my field of expertise and what I have witnessed with this project something very wrong is happening here and the information does simply not add up. I oppose the NZTA Makays to Peka Peka proposal and would like to tell you my experience and explain my findings. Lead Up We moved from Auckland to Kapiti (originally to Raumati South) in 2007 to start a family and fell in love with the community and surroundings. The combination of bush, beach, and lifestyle was an easy decision. We heard about KCDCs initial proposal to create a new alternate road and bridge to Waikanae I quite liked the idea. It seems a little crazy that you can almost walk to Waikanae from Paraparaumu Beach faster than you can drive (we tested it the other day). A year or two later we received the notification from NZTA that as part of the Roads of National Significance project they were planning to upgrade the existing SH1 to future proof the national grid. We again quite optimistic when we saw the proposals (WO and EO only) and chose option EO, upgrade the existing SH1, as it had minimal impact on the existing community leaving SH1 as close to its original location as possible. -

MONDAY 17 May TIME Individual/ Orgainisation Speaker for Organisation Submission Number 9:30 A.M

MONDAY 17 May TIME Individual/ Orgainisation Speaker for Organisation Submission Number 9:30 a.m. - 9:45 a.m. 9:45 a.m. - 10:00 a.m. KCA Lyn Sleath 21LTP -12 + 21 10:00 a.m. - 10:15 a.m. Raumati Village Business Association Bede Laracy 21 LTP - 08 10:15 a.m. - 10:30 a.m. John Robinson EHQ - 01 10:30 a.m. - 10:45 a.m. Marco Zeeman EHQ - 10 10:45 a.m. - 11:00 a.m. Georgia Choveaux EHQ - 16 11:00 a.m. - 11:15 a.m. MORNING TEA BREAK 11:15 a.m. - 11:30 a.m. E Tu Otaki Shelley Warwick/someone else 21LTP - 22 11:30 a.m. - 11:45 a.m. KEAG Shelley Warwick/ Ruth Halliday 21 LTP - 23 & 21 LTP - 26 11:45 a.m. - 12:00 p.m. Kapiti College Tony Kane 21LTP74 12:00 p.m. - 12:15 p.m. Waik Community Board James Westbury EHQ - 29 12:15 p.m. - 12:30 p.m. Adrian Gregory EHQ-58 12:30 p.m. - 1:30 p.m. LUNCH BREAK 1:30 p.m. - 1:45 p.m. John Le Harivel EHQ - 13 1:45 p.m. - 2:00 p.m. Peter Ryan EHQ - 09 2:00 p.m. - 2:15 p.m. Nga Manu Matu Booth 21LTP - 11 2:15 p.m. - 2:30 p.m. Kapiti Climate Change Action Dawn Brook 21LTP - 56 2:30 p.m. - 2:45 p.m. Rachel Barwell 21LTP - 54 2:45 p.m. - 3:00 p.m. Shaun Johnson EHQ - 06 3:00 p.m. -

Final Client Report

Final Client Report Prepared for Kapiti Coast District Council September 2005 A Study of the Rural Productive Potential in the Northern Part of the Kapiti Coast District Alec Mackay, AgResearch, Palmerston North Brent Clothier, Hort Research, Palmerston North Tessa Mills, Hort Research, Palmerston North Murray Jessen, Landcare Research, Palmerston North Peter Newsome, Landcare Research, Palmerston North Janice Willoughby, Landcare Research, Palmerston North Jeff Reid, Crop and Food Research, Palmerston North Jeremy Neild, PGG Wrightson Consulting, Feilding A Study of the Rural Productive Potential in the Northern Part of the Kapiti Coast District Prepared for Kapiti Coast District Council September 2005 Alec Mackay, AgResearch, Palmerston North Brent Clothier, Hort Research, Palmerston North Tessa Mills, Hort Research, Palmerston North Murray Jessen, Landcare Research, Palmerston North Peter Newsome, Landcare Research, Palmerston North Janice Willoughby, Landcare Research, Palmerston North Jeff Reid, Crop and Food Research, Palmerston North Jeremy Neild, PGG Wrightson Consulting, Feilding DISCLAIMER: While all reasonable endeavour has been made to ensure the accuracy of the investigations and the information contained in this report, AgResearch expressly disclaims any and all liabilities contingent or otherwise that may arise from the use of the information. COPYRIGHT : All rights are reserved worldwide. No part of this publication may be copied, photocopied, reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form -

Private Plan Change Request to Kapiti Coast District Plan

PRIVATE PLAN CHANGE REQUEST TO KAPITI COAST DISTRICT PLAN AIRPORT ZONE: PROHIBITED ACTIVITIES Prepared for KAPITI COAST AIRPORT HOLDINGS LIMITED By RUSSELL McVEAGH February 2016 3015556 THE RESOURCE MANAGEMENT ACT 1991 REQUEST FOR CHANGE TO THE KAPITI COAST DISTRICT PLAN BY KAPITI COAST AIRPORT HOLDINGS LIMITED KAPITI COAST AIRPORT HOLDINGS LIMITED ("KCAHL"), has requested changes to the Operative Kapiti Coast District Plan under Clause 21 of Part 2 of the First Schedule to the Resource Management Act ("RMA" or "Act"), as set out below. The subject of this application is the classification of certain prohibited activities in the Airport Zone of the Operative Kapiti Cost District Plan ("District Plan"). The changes sought to the District Plan are to remove prohibited activity status in relation to the specified activities as follows: 1. Amend Rule D.9.1.6(i) to provide that noise sensitive activities outside of the Air Noise Boundary not specifically provided for as a permitted activity are classified as a discretionary activity. 2. Amend Rule D.9.1.6(ii) to provide for one only Department Store to be classified as a non- complying activity. 3. Amend Rule D.9.1.6(iii) to provide for one only supermarket to be classified as a discretionary activity. 4. Amend Rule D.9.1.6(iv) to provide that more than one store of between 151m2 and 1,500m2 gross floor area that retails groceries or non-specified food lines to be classified as a discretionary activity. 5. Any consequential amendments to the District Plan that may be necessary to achieve the purpose of this private plan change request. -

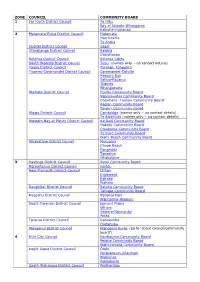

CB List by Zone and Council

ZONE COUNCIL COMMUNITY BOARD 1 Far North District Council Te Hiku Bay of Islands-Whangaroa Kaikohe-Hokianga 2 Matamata-Piako District Council Matamata Morrinsville Te Aroha Opotiki District Council Coast Otorohanga District Council Kawhia Otorohanga Rotorua District Council Rotorua Lakes South Waikato District Council Tirau (names only – no contact details) Taupo District Council Turangi- Tongariro Thames-Coromandel District Council Coromandel-Colville Mercury Bay Tairua-Pauanui Thames Whangamata Waikato District Council Huntly Community Board Ngaruawahia Community Board Onewhero -Tuakau Community Board Raglan Community Board Taupiri Community Board Waipa District Council Cambridge (names only – no contact details) Te Awamutu (names only – no contact details) Western Bay of Plenty District Council Katikati Community Board Maketu Community Board Omokoroa Community Board Te Puke Community Board Waihi Beach Community Board Whakatane District Council Murupara Ohope Beach Rangitaiki Taneatua Whakatane 3 Hastings District Council Rural Community Board Horowhenua District Council Foxton New Plymouth District Council Clifton Inglewood Kaitake Waitara Rangitikei District Council Ratana Community Board Taihape Community Board Ruapehu District Council National Park Waimarino-Waiouru South Taranaki District Council Egmont Plains Eltham Hawera-Normanby Patea Tararua District Council Dannevirke Eketahuna Wanganui District Council Wanganui Rural (go to ‘about council/community board’) 4 Hutt City Council Eastbourne Community Board Petone Community Board -

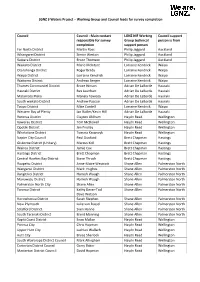

LGNZ 3 Waters Working Group and Council Leads for Survey Completion

LGNZ 3 Waters Project – Working Group and Council leads for survey completion Council Council - Main contact LGNZ NIF Working Council support responsible for survey Group technical person is from completion support person Far North District Martin Ross Philip Jaggard Auckland Whangarei District Simon Weston Philip Jaggard Auckland Kaipara District Bruce Thomson Philip Jaggard Auckland Waikato District Marie McIntyre Lorraine Kendrick Waipa Otorohanga District Roger Brady Lorraine Kendrick Waipa Waipa District Lorraine Kendrick Lorraine Kendrick Waipa Waitomo District Andreas Senger Lorraine Kendrick Waipa Thames Coromandel District Bruce Hinson Adrian De LaBorde Hauraki Hauraki District Rex Leonhart Adrian De LaBorde Hauraki Matamata Piako Manaia Tewiata Adrian De LaBorde Hauraki South waikato District Andrew Pascoe Adrian De LaBorde Hauraki Taupo District Mike Cordell Lorraine Kendrick Waipa Western Bay of Plenty Ian Butler/Kevin Hill Adrian De LaBorde Hauraki Rotorua District Clayton Oldham Haydn Read Wellington Kawerau District Tom McDowell Haydn Read Wellington Opotiki District Jim Findlay Haydn Read Wellington Whakatane District Tomasz Krawczyk Haydn Read Wellington Napier City Council Paul Dunford Brett Chapman Hastings Gisborne District (Unitary) Marcus Koll Brett Chapman Hastings Wairoa District Jamie Cox Brett Chapman Hastings Hastings District Brett Chapman Brett Chapman Hastings Central Hawkes Bay District Steve Thrush Brett Chapman Hastings Ruapehu District Anne-Maire Westcott Shane Allen Palmerston North Wanganui District