2-Łamanie Prace Historyczne Zeszyt 4.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quipment of Georgios Maniakes and His Army According to the Skylitzes Matritensis

ΠΟΡΦΥΡΑ da un’idea di Nicola Bergamo “Saranno come fiori che noi coglieremo nei prati per abbellire l’impero d’uno splendore incomparabile. Come specchio levigato di perfetta limpidezza, prezioso ornamento che noi collocheremo al centro del Palazzo” La prima rivista on-line che tratta in maniera completa il periodo storico dei Romani d’Oriente Anno 2005 Dicembre Supplemento n 4 A Prôtospatharios, Magistros, and Strategos Autokrator of 11th cent. : the equipment of Georgios Maniakes and his army according to the Skylitzes Matritensis miniatures and other artistic sources of the middle Byzantine period. a cura di: Dott. Raffaele D’Amato A Prôtospatharios, Magistros, and Strategos Autokrator of 11th cent. the equipment of Georgios Maniakes and his army according to the Skylitzes Matritensis miniatures and other artistic sources of the middle Byzantine period. At the beginning of the 11th century Byzantium was at the height of its glory. After the victorious conquests of the Emperor Basil II (976-1025), the East-Roman1 Empire regained the sovereignty of the Eastern Mediterranean World and extended from the Armenian Mountains to the Italian Peninsula. Calabria, Puglia and Basilicata formed the South-Italian Provinces, called Themata of Kalavria and Laghouvardhia under the control of an High Imperial Officer, the Katepano. 2But the Empire sought at one time to recover Sicily, held by Arab Egyptian Fatimids, who controlled the island by means of the cadet Dynasty of Kalbits.3 The Prôtospatharios4 Georgios Maniakes was appointed in 1038 by the -

Policy Notes March 2021

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY MARCH 2021 POLICY NOTES NO. 100 In the Service of Ideology: Iran’s Religious and Socioeconomic Activities in Syria Oula A. Alrifai “Syria is the 35th province and a strategic province for Iran...If the enemy attacks and aims to capture both Syria and Khuzestan our priority would be Syria. Because if we hold on to Syria, we would be able to retake Khuzestan; yet if Syria were lost, we would not be able to keep even Tehran.” — Mehdi Taeb, commander, Basij Resistance Force, 2013* Taeb, 2013 ran’s policy toward Syria is aimed at providing strategic depth for the Pictured are the Sayyeda Tehran regime. Since its inception in 1979, the regime has coopted local Zainab shrine in Damascus, Syrian Shia religious infrastructure while also building its own. Through youth scouts, and a pro-Iran I proxy actors from Lebanon and Iraq based mainly around the shrine of gathering, at which the banner Sayyeda Zainab on the outskirts of Damascus, the Iranian regime has reads, “Sayyed Commander Khamenei: You are the leader of the Arab world.” *Quoted in Ashfon Ostovar, Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (2016). Khuzestan, in southwestern Iran, is the site of a decades-long separatist movement. OULA A. ALRIFAI IRAN’S RELIGIOUS AND SOCIOECONOMIC ACTIVITIES IN SYRIA consolidated control over levers in various localities. against fellow Baathists in Damascus on November Beyond religious proselytization, these networks 13, 1970. At the time, Iran’s Shia clerics were in exile have provided education, healthcare, and social as Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi was still in control services, among other things. -

THE REIGN of AL-IHAKIM Bl AMR ALLAH ‘(386/996 - 41\ / \ Q 2 \ % "A POLITICAL STUDY"

THE REIGN OF AL-IHAKIM Bl AMR ALLAH ‘(386/996 - 41\ / \ Q 2 \ % "A POLITICAL STUDY" by SADEK ISMAIL ASSAAD Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London May 1971 ProQuest Number: 10672922 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672922 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT The present thesis is a political study of the reign of al-Hakim Bi Amr Allah the sixth Fatimid Imam-Caliph who ruled between 386-411/ 996-1021. It consists of a note on the sources and seven chapters. The first chapter is a biographical review of al-Hakim's person. It introduces a history of his birth, childhood, succession to the Caliphate, his education and private life and it examines the contradiction in the sources concerning his character. Chapter II discusses the problems which al-Hakim inherited from the previous rule and examines their impact on the political life of his State. Chapter III introduces the administration of the internal affairs of the State. -

Hussain Ali Tahtooh

3=;;5?3819 ?591A8=<@ 25AC55< A75 1?12 C=?94 1<4 8<481 !)?4 1<4 *A7%.A7 1<4 '&A7 35<AB?85@" 7VTTDLP 1NL ADKUQQK 1 AKHTLT @VEOLUUHG IQS UKH 4HJSHH QI >K4 DU UKH BPLWHSTLUZ QI @U$ 1PGSHXT '.-, 6VNN OHUDGDUD IQS UKLT LUHO LT DWDLNDENH LP ?HTHDSFK0@U1PGSHXT/6VNNAHYU DU/ KUUR/%%SHTHDSFK#SHRQTLUQSZ$TU#DPGSHXT$DF$VM% >NHDTH VTH UKLT LGHPULILHS UQ FLUH QS NLPM UQ UKLT LUHO/ KUUR/%%KGN$KDPGNH$PHU%'&&()%(.++ AKLT LUHO LT RSQUHFUHG EZ QSLJLPDN FQRZSLJKU COMMII' hAl1 J1:IATroNH 1IITWEJN THE ARAB WORLD AND INDIA (.IRI) AN]) 4Th / 9111 AND 10TH CENTURIES) By ' Hussahi All. Tahtooh fl.I., Baghdad M.A., Mosul A llIofll!3 nulitnitted fo! the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the lJiilveislty of St. Andrews. • AiiIro'n December 1986. AI3STRACT 1:1,13 t)IeIlent woik Is mainly concerned with the commercial relations I)etweon the Arab world and India In the 3rd and 4th / 9th and 10th centurIes. The thesis consists of an Introduction and five chapters. The lntwdiictloit contains a brief survey of the historical background to the A,iih-Iiidkin trade links In the period prior to the period of the research. lt also Includes the reasons for choosing the subject, and the t1I[ficiiltles with which the research was faced. The intro(1(I(II Iin niso conta his the methods of the research and a study of the ma lit S ( 3LIt (iCS (1iipter One deals with the Arab provinces, the main kingdoms of India, Iho political situation in the Arab world and India, and its effecis iiii the Enhliject. -

Sona Grigoryan Supervisor: Aziz Al-Azmeh

Doctoral Dissertation POETICS OF AMBIVALENCE IN AL-MA‘ARRĪ’S LUZŪMĪYĀT AND THE QUESTION OF FREETHINKING by Sona Grigoryan Supervisor: Aziz Al-Azmeh Submitted to the Medieval Studies Department, Central European University, Budapest In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Medieval Studies CEU eTD Collection Budapest 2018 TABLE OF CONTENT Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................. iv List of Abbreviations................................................................................................................................. v Some Matters of Usage ............................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Al-Ma‘arrī-an Intriguing Figure ........................................................................................................ 1 2. The Aim and Focus of the Thesis ....................................................................................................... 4 3. Working Material ............................................................................................................................ 13 CHAPTER 1. AL-MA‘ARRĪ AND HIS CONTEXT ............................................................................... 15 1.1. Historical Setting -

HISTORY of the MIDDLE EAST a Research Project of Fairleigh Dickinson University By

HISTORY OF THE MIDDLE EAST a Research Project of Fairleigh Dickinson University by Amanuel Ajawin Amer Al-Hajri Waleed Al-Saiyani Hamad Al-Zaabi Baya Bensmail Clotilde Ferry Feridun Kul Gabriela Garcia Zina Ibrahem Lorena Giminez Jose Manuel Mendoza-Nasser Abdelghani Merabet Alice Mungwa Isabelle Rakotoarivelo Seddiq Rasuli Antonio Nico Sabas Coumba Santana Ashley Toth Fabrizio Trezza Sharif Ahmad Waheedi Mohammad Fahim Yarzai Mohammad Younus Zaidullah Zaid Editor: Ahmad Kamal Published by: Fairleigh Dickinson University 1000 River Road Teaneck, NJ 07666 USA January 2012 ISBN: 978-1-4507-9087-1 The opinions expressed in this book are those of the authors alone, and should not be taken as necessarily reflecting the views of Fairleigh Dickinson University, or of any other institution or entity. © All rights reserved by the authors No part of the material in this book may be reproduced without due attribution to its specific author. THE AUTHORS Amanuel Ajawin, a Diplomat from Sudan Amer Al-Hajri, a Diplomat from Oman Waleed Al-Saiyani, a Graduate Student from Yemen Hamad Al-Zaabi, a Diplomat from the UAE Baya Bensmail, a Diplomat from Algeria Clotilde Ferry, a Graduate Student from Monaco Ahmad Kamal, a Senior Fellow at the United Nations Feridun Kul, a Graduate Student from Afghanistan Gabriela Garcia, a Diplomat from Ecuador Lorena Giminez, a Diplomat from Venezuela Zina Ibrahem, a Civil Servant from Iraq Jose Manuel Mendoza, a Graduate Student from Honduras Abdelghani Merabet, a Graduate Student from Algeria Alice Mungwa, a Graduate Student -

GREEK MANUSCRIPTS in the EARLY ABBASID EMPIRE: Fiction

345 GREEK MANUSCRIPTS IN THE EARLY ABBASID EMPIRE 346 same institution were attached astronomical observatories (…), one in Baghdâd, another one in Damascus”. In the same article the author adds, that “it appears in fact that the library so constituted, and often called Khizânat al-Ìikma, already existed in the time of al-Rashîd and the Barmakids who had begun to have Greek works translated. Al-Ma'mûn may only have given a new impetus to this movement which was later to exert a considerable influence on the development of Islamic thought and culture”.2) The Cambridge History of Islam does not speak of an ear- lier existence of the Bayt- or Khizânat al-Îikma. It speaks of the “Bayt al-Îikma of the Caliph al-Ma'mûn with its many Greek manuscripts” and of 833 as the year in which this insti- tution of learning had been founded by him. It relates that Al- Ma'mûn had sent the Christian scholar Îunayn ibn IsÌâq “to accompany the mission to Byzantium in search of good man- uscripts” and consequently had “gathered around him an excellent team of translators”. Again, in another passage, the Bayt al-Îikma is called “the central institute for translations GREEK MANUSCRIPTS set up by the Abbasid Caliph Al-Ma'mûn”.3) IN THE EARLY ABBASID EMPIRE: In assessing its accessibility to readers, several authors Fiction and Facts about their Origin, described the “House of Wisdom” as a public library or even Translation and Destruction as “the first public library in Islam”4) or rather as one of the academies “open to all those who were qualified to benefit The Abbasid Caliph Al-Ma'mûn (who reigned in Baghdad from them”5) According to Heffening and Pearson6) “the first from 813-833) emerges from ancient sources and modern public libraries [in Islam] formed a fundamental part of the studies as the key-figure in the translation process from Greek first academies known as bayt al-Ìikma”. -

1 Overview of Saudi–Iranian Relations 1

Notes 1 Overview of Saudi–Iranian Relations 1. Saudi Arabia and Iran share at least three joint oilfields, each known by its Persian or Arabic name, respectively: Esfandiar/Al Louloua, Foroozan/Marjan, and Farzad/Hasbah. Arash/Al Dorrah is shared between Iran, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia. The three states have yet to reach an agreement over the demarca- tion of the maritime boundary in the northern Persian Gulf that affects the field. Iran’s share of the Esfandiar and Foroozan fields has dropped to levels that make their further development uneconomic, in part due to Saudi ability to extract faster from the fields. Saudi Arabia and Iran signed an agreement to develop the Farzad/Hasbah A gas field in January 2012, and were scheduled to sign a second agreement to develop the Farzad B gas field and Arash/Al Dorrah oilfield, pend- ing the removal of international sanctions against Iran. In 2014, they contested their respective shares in the Arash/Al Dorrah. 2 . British administration in the Persian Gulf began in 1622, when the British fleet helped the Persian Safavid king, Shah Abbas, expel the Portuguese from Hormuz island. The period of the British Residency of the Persian Gulf as an official colonial subdivision extended from 1763 to 1971. 3 . Interview with Abdulaziz Sager, chairman of Gulf Research Center, Riyadh, November 30, 2011. 4 . Alinaqi Alikhani, yad dasht ha-yi asaddollah alam , jeld shesh, 1355–1356 [The Diaries of Alam], vol. 6, 1975–1976 (tehran: entesharat maziar va moin, 1377), pp. 324–325; 464. When the shah insists that the United States should under- stand that it cannot make Iran “a slave [puppet] government,” Alam informs him that the Americans have tried to make contact with different groups in Iranian society—alluding to dissidents. -

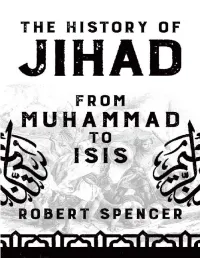

The History of Jihad: from Muhammad to ISIS

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR THE HISTORY OF JIHAD “Robert Spencer is one of my heroes. He has once again produced an invaluable and much-needed book. Want to read the truth about Islam? Read this book. It depicts the terrible fate of the hundreds of millions of men, women and children who, from the seventh century until today, were massacred or enslaved by Islam. It is a fate that awaits us all if we are not vigilant.” —Geert Wilders, member of Parliament in the Netherlands and leader of the Dutch Party for Freedom (PVV) “From the first Arab-Islamic empire of the mid-seventh century to the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the story of Islam has been the story of the rise and fall of universal empires and, no less importantly, of never quiescent imperialist dreams. In this tour de force, Robert Spencer narrates the transformation of the concept of jihad, ‘exertion in the path of Allah,’ from a rallying cry for the prophet Muhammad’s followers into a supreme religious duty and the primary vehicle for the expansion of Islam throughout the ages. A must-read for anyone seeking to understand the roots of the Manichean struggle between East and West and the nature of the threat confronted by the West today.” —Efraim Karsh, author of Islamic Imperialism: A History “Spencer argues, in brief, ‘There has always been, with virtually no interruption, jihad.’ Painstakingly, he documents in this important study how aggressive war on behalf of Islam has, for fourteen centuries and still now, befouled Muslim life. He hopes his study will awaken potential victims of jihad, but will they—will we—listen to his warning? Much hangs in the balance.” —Daniel Pipes, president, Middle East forum and author of Slave Soldiers and Islam: The Genesis of a Military System “Robert Spencer, one of our foremost analysts of Islamic jihad, has now written a historical survey of the doctrine and practice of Islamic sanctified violence. -

Byzantine Military Tactics in Syria and Mesopotamia in the Tenth Century

Byzantine Military Tactics in Syria and Mesopotamia in the Tenth Century 5908_Theotokis.indd i 14/09/18 11:38 AM 5908_Theotokis.indd ii 14/09/18 11:38 AM BYZANTINE MILITARY TACTICS IN SYRIA AND MESOPOTAMIA IN THE TENTH CENTURY A Comparative Study Georgios Theotokis 5908_Theotokis.indd iii 14/09/18 11:38 AM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Georgios Theotokis, 2018 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/ 13 JaghbUni Regular by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 3103 3 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 3105 7 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 3106 4 (epub) The right of Georgios Theotokis to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 5908_Theotokis.indd iv 14/09/18 11:38 AM Contents Acknowledgements vi List of Rulers vii Map 1 Anatolia and Upper Mesopotamia viii Map 2 Armenian Themes and Pri ncipalities ix Introduction 1 1 The ‘Grand Strategy’ of the Byzantine Empire 23 2 Byzantine and Arab Strategies and Campaigning Tactics in Cilicia and Anatolia (Eighth–Tenth Centuries) 52 3 The Empire’s Foreign Policy in the East and the Key Role of Armenia (c. -

Leo the Deacon

The History of Leo the Deacon Byzantine Military Expansion in the Tenth Century Introduction, translation, and annotations by Alice-Mary Talbot and Denis F. Sullivan Dumbarton Oaks Studies XLI THE HISTORY OF LEO THE DEACON THE HISTORY OF LEO THE DEACON Byzantine Military Expansion in the Tenth Century Introduction, translation, and annotations by Alice-Mary Talbot and Denis F. Sullivan with the assistance of George T. Dennis and Stamatina McGrath Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. © 2005 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University Washington, D.C. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Leo, the Deacon, b. ca. 950. [ History. English] The History of Leo the Deacon : Byzantine military expansion in the tenth century / introduction, translation, and annotations by Alice-Mary Talbot and Denis F. Sullivan ; with the assistance of George T. Dennis and Stamatina McGrath. p. cm. History translated into English from the original Greek; critical matter in English. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-88402-306-0 1. Byzantine Empire—History, Military—527-1081. I. Talbot, Alice-Mary Maffry. II. Sullivan, Denis. III.Title. DF543.L46 2005 2005003088 Contents Preface and Acknowledgments vii Abbreviations χ Introduction A The Byzantine Empire in the Tenth Century: Outline of Military and Political Events 1 Β The Byzantine Military in the Tenth Century 4 C Biography of Leo the Deacon 9 D Leo as a "Historian" 11 Ε Manuscript Tradition of the History 50 -

In Studies in Byzantine Sigillography, I, Ed. N. Oikonomides (Washington, D.C., 1987), Pp

Notes I. SOURCES FOR EARLY MEDIEVAL BYZANTIUM 1. N. Oikonomides, 'The Lead Blanks Used for Byzantine Seals', in Studies in Byzantine Sigillography, I, ed. N. Oikonomides (Washington, D.C., 1987), pp. 97-103. 2. John Lydus, De Magistratibus, in Joannes Lydus on Powers, ed. A. C. Bandy (Philadelphia, Penn., 1983), pp. 160-3. 3. Ninth-century deed of sale (897): Actes de Lavra, 1, ed. P. Lemerle, A. Guillou and N. Svoronos (Archives de l'Athos v, Paris, 1970), pp. 85-91. 4. For example, G. Duby, La societe aux xi' et xii' sii!cles dans la region maconnaise, 2nd edn (Paris, 1971); P. Toubert, Les structures du Latium medieval, 2 vols (Rome, 1973). 5. DAI, cc. 9, 46, 52, pp. 56-63, 214-23, 256-7. 6. De Cer., pp. 651-60, 664-78, 696-9. 7. See S. D. Goitein, A Mediterranean Society, 5 vols (Berkeley, Cal., 1967- 88), I, pp. 1-28. , 8. ]. Darrouzes, Epistoliers byzantins du x' sii!cle (Archives de I' orient Chretien VI, Paris, 1960), pp. 217-48. 9. Photius, Epistulae et Amphilochia, ed. B. Laourdas and L. G. Westerink, 6 vols (Leipzig, 1983-8), pope: nrs 288, 290; III, pp. 114-20, 123-38, qaghan of Bulgaria: nrs 1, 271, 287; 1, pp. 1-39; II, pp. 220-1; III, p. 113-14; prince of princes of Armenia: nrs 284, 298; III, pp. 1-97, 167-74; katholikos of Armenia: nr. 285; III, pp. 97-112; eastern patriarchs: nrs 2, 289; 1, pp. 39-53; III, pp. 120-3; Nicholas I, patriarch of Constantinople, Letters, ed.