Deforestation of Primate Habitat on Sumatra and Adjacent Islands, Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primates of the Southern Mentawai Islands

Primate Conservation 2018 (32): 193-203 The Status of Primates in the Southern Mentawai Islands, Indonesia Ahmad Yanuar1 and Jatna Supriatna2 1Department of Biology and Post-graduate Program in Biology Conservation, Tropical Biodiversity Conservation Center- Universitas Nasional, Jl. RM. Harsono, Jakarta, Indonesia 2Department of Biology, FMIPA and Research Center for Climate Change, University of Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia Abstract: Populations of the primates native to the Mentawai Islands—Kloss’ gibbon Hylobates klossii, the Mentawai langur Presbytis potenziani, the Mentawai pig-tailed macaque Macaca pagensis, and the snub-nosed pig-tailed monkey Simias con- color—persist in disturbed and undisturbed forests and forest patches in Sipora, North Pagai and South Pagai. We used the line-transect method to survey primates in Sipora and the Pagai Islands and estimate their population densities. We walked 157.5 km and 185.6 km of line transects on Sipora and on the Pagai Islands, respectively, and obtained 93 sightings on Sipora and 109 sightings on the Pagai Islands. On Sipora, we estimated population densities for H. klossii, P. potenziani, and S. concolor in an area of 9.5 km², and M. pagensis in an area of 12.6 km². On the Pagai Islands, we estimated the population densities of the four primates in an area of 11.1 km². Simias concolor was found to have the lowest group densities on Sipora, whilst P. potenziani had the highest group densities. On the Pagai Islands, H. klossii was the least abundant and M. pagensis had the highest group densities. Primate populations, notably of the snub-nosed pig-tailed monkey and Kloss’ gibbon, are reduced and threatened on the southern Mentawai Islands. -

A Radiographic Study of Human-Primate Commensalism

Developments in Primatology: Progress and Prospects Series Editor Russell H. Tuttle Department of Anthropology The University of Chicago For further volumes, go to http://www.springer.com/series/5852 Sharon Gursky-Doyen ● Jatna Supriatna Editors Indonesian Primates Editors Sharon Gursky-Doyen Jatna Supriatna Department of Anthropology Conservation International Indonesia Texas A&M University University of Indonesia College Station, TX Jakarta USA Indonesia [email protected] [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-1559-7 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-1560-3 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-1560-3 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London Library of Congress Control Number: 2009942275 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) S.L. Gursky-Doyen dedicates this volume to her parents, Ronnie Bender and Burt Gursky, who after all these years still do not really know what she does, but they proudly display her books on their coffee table; and to her husband Jimmie who taught her what love is. -

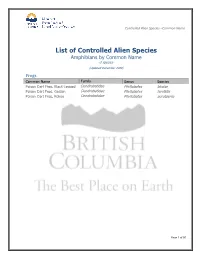

Controlled Alien Species -Common Name

Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Amphibians by Common Name -3 species- (Updated December 2009) Frogs Common Name Family Genus Species Poison Dart Frog, Black-Legged Dendrobatidae Phyllobates bicolor Poison Dart Frog, Golden Dendrobatidae Phyllobates terribilis Poison Dart Frog, Kokoe Dendrobatidae Phyllobates aurotaenia Page 1 of 50 Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Birds by Common Name -3 species- (Updated December 2009) Birds Common Name Family Genus Species Cassowary, Dwarf Cassuariidae Casuarius bennetti Cassowary, Northern Cassuariidae Casuarius unappendiculatus Cassowary, Southern Cassuariidae Casuarius casuarius Page 2 of 50 Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Mammals by Common Name -437 species- (Updated March 2010) Common Name Family Genus Species Artiodactyla (Even-toed Ungulates) Bovines Buffalo, African Bovidae Syncerus caffer Gaur Bovidae Bos frontalis Girrafe Giraffe Giraffidae Giraffa camelopardalis Hippopotami Hippopotamus Hippopotamidae Hippopotamus amphibious Hippopotamus, Madagascan Pygmy Hippopotamidae Hexaprotodon liberiensis Carnivora Canidae (Dog-like) Coyote, Jackals & Wolves Coyote (not native to BC) Canidae Canis latrans Dingo Canidae Canis lupus Jackal, Black-Backed Canidae Canis mesomelas Jackal, Golden Canidae Canis aureus Jackal Side-Striped Canidae Canis adustus Wolf, Gray (not native to BC) Canidae Canis lupus Wolf, Maned Canidae Chrysocyon rachyurus Wolf, Red Canidae Canis rufus Wolf, Ethiopian -

An Assessment of Trade in Gibbons and Orang-Utans in Sumatra, Indoesia

AN ASSESSMENT OF TRADE IN GIBBONS AND ORANG-UTANS IN SUMATRA, INDONESIA VINCENT NIJMAN A TRAFFIC SOUTHEAST ASIA REPORT Published by TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia © 2009 TRAFFIC Southeast Asia All rights reserved. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC Southeast Asia as the copyright owner. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC Network, WWF or IUCN. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. Layout by Noorainie Awang Anak, TRAFFIC Southeast Asia Suggested citation: Vincent Nijman (2009). An assessment of trade in gibbons and orang-utans in Sumatra, Indonesia TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia ISBN 9789833393244 Cover: A Sumatran Orang-utan, confiscated in Aceh, stares through the bars of its cage Photograph credit: Chris R. Shepherd/TRAFFIC Southeast Asia An assessment of trade in gibbons and orang-utans in Sumatra, Indonesia Vincent Nijman Cho-fui Yang Martinez -

Research Articles NAT

Research articles NAT. HIST. BULL. SIAM SOC. 61(1): 7–14, 2015 PERSISTENCE OF PRIMATE AND UNGULATE COMMUNITIES ON FORESTED ISLANDS IN LAKE KENYIR IN NORTHERN PENINSULAR MALAYSIA Ding Li Yong 1,2 ABSTRACT As more rivers in Southeast Asia’s forested landscapes are dammed, artificial land-bridge islands are becoming more ubiquitous. While the mammal faunas on these islands are poorly studied, they provide unique opportunities to investigate the impacts of fragmentation and isolation on insular biota. During the course of a 60-day survey of small (<20 ha), medium (20–50 ha) and large (>50 ha) forested islands in Lake Kenyir, Peninsular Malaysia, four primates and three ungulate species were detected on these islands, while the entire complement of six primates were found at nearby mainland sites. Five ungulates were detected on mainland sites. Notably, white-thighed surili (Presbytis siamensis) and white-handed gibbon (Hylobates lar) were found to have persisted on islands as small as 1.1 ha two decades post-isolation, although no ungulates were observed on the three smallest (<10 ha) islands. Observed diversity patterns of primate and ungulate assemblages on forest islands may be the result of patchy, resource-influenced distributions pre-flooding, and differential abilities to disperse across the water matrix post-flooding. Further studies should resample species occurrence, on top of collecting data on abundance, demographics and genetic variability in these isolated mammalian communities. Keywords: dams, isolation, Lake Kenyir, mammals, Peninsular Malaysia, Southeast Asia INTRODUCTION Mammalian communities on tropical land-bridge islands worldwide have been little studied but are increasingly relevant in the light of understanding persistence patterns in small habitat patches as tropical forests become rapidly lost and fragmented globally (RIITTERS ET AL., 2000; GIBSON ET AL., 2013). -

In Mentawai Islands, Indonesia

BIODIVERSITAS ISSN: 1412-033X Volume 21, Number 5, May 2020 E-ISSN: 2085-4722 Pages: 2224-2232 DOI: 10.13057/biodiv/d210551 Distribution survey of Kloss’s Gibbons (Hylobates klosii) in Mentawai Islands, Indonesia ARIF SETIAWAN1,♥, CHRISTIAN SIMANJUNTAK2, ISMAEL SAUMANUK3, DAMIANUS TATEBURUK3, YOAN DINATA2, DARMAWAN LISWANTO2, ANJAR RAFIASTANTO2 1Swaraowa. Kalipenthung, Kalitirto, Berbah, Sleman 55573, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. email: [email protected] 2Fauna and Flora International Indonesia. Jl. Margasatwa Raya, Komplek Margasatwa Baru No. A7, Pondok Labu, Cilandak, Jakarta Selatan 12450, Jakarta, Indonesia 3Malinggai Uma Tradisional Mentawai. Dusun Puro 2, Desa Mailepet, Kecamatan Siberut Selatan, Kepulauan Mentawai 25393, West Sumatra, Indonesia Manuscript received: 6 February 2020. Revision accepted: 26 April 2020. Abstract. Setiawan A, Simanjuntak C, Saumanuk I, Tateburuk D, Dinata Y, Liswanto D, Rafiastanto A. 2020. Distribution survey of Kloss’s Gibbons (Hylobates klosii) in Mentawai Islands, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 21: 2224-2232. The aim of this study was to assess the population density, distribution, habitats, and threats of Kloss’s gibbon (Hylobates klossii) in the Mentawai Islands, Indonesia. In 2011- 2012 we conducted a survey on Siberut Island, outside of the National Park, as well as a short visit to Sipora, North Pagai, and South Pagai. From March to September 2017, we surveyed once again some previous localities on the Siberut and Sipora islands to keep up to date with recent developments on the ground. On Siberut we used an auditory sampling method through fixed point counts, combined with line transects, to estimate the gibbon densities. In total, 113-morning calls were recorded from 13 Listening Points; 75 of these were used for density calculations. -

LEAF MONKEY, Trachypithecus Auratus Sondaicus, in the PANGANDARAN NATURE RESERVE, WEST JAVA, INDONESIA

BEHAVIOURAL ECOLOGY OF THE SILVER LEAF MONKEY, Trachypithecus auratus sondaicus, IN THE PANGANDARAN NATURE RESERVE, WEST JAVA, INDONESIA by KAREN MARGARETHA KOOL A dissertation submitted to the University of New South Wales for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Science University of New South Wales Sydney, New South Wales Australia March, 1989 SR PT02 Form 2 RETENTION THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES DECLARATION RELATING TO DISPOSITION OF PROJECT REPORT/THESIS This is to certify that I . .1�9.-.C:eo...... MQ;.r.tQ.J:£'\hP..-. .. .J�l.... being a candidate for the degree of 1)!=>.d:o.r.--.of.-.Y.hSos.Of.hy .. am fully aware of the policy of the University relating to the retention and use of higherdegree project reports and theses, namely that the University retains the copies submitted for examination and is free to allow them to be consulted or borrowed. Subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act, 1968, the University may issue a project report or thesis in whole or in part, in photostat or microfilm or other copying medium. In the light of these provisions I declare that I wish to retain my full privileges of copyright and request that neither the whole nor any portion of my project report/thesis be published by the University Librarian and that the Librarian may not authorise the publication of the whole or any part of it, and that I further declare that thispreservation of my copyright privileges shall lapse from the ... :fit.�t ............ day of ...3.o.n ....... 9..r: { ............... 19.�.<:\................. -

The World's 25 Most Endangered Primates, 2006-2008

Primate Conservation 2007 (22): 1 – 40 Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates, 2006 – 2008 Russell A. Mittermeier 1, Jonah Ratsimbazafy 2, Anthony B. Rylands 3, Liz Williamson 4, John F. Oates 5, David Mbora 6, Jörg U. Ganzhorn 7, Ernesto Rodríguez-Luna 8, Erwin Palacios 9, Eckhard W. Heymann 10, M. Cecília M. Kierulff 11, Long Yongcheng 12, Jatna Supriatna 13, Christian Roos 14, Sally Walker 15, and John M. Aguiar 3 1Conservation International, Arlington, VA, USA 2Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust – Madagascar Programme, Antananarivo, Madagascar 3Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation International, Arlington, VA, USA 4Department of Psychology, University of Stirling, Stirling, Scotland, UK 5Department of Anthropology, Hunter College, City University of New York (CUNY), New York, USA 6Department of Biological Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA 7Institute of Zoology, Ecology and Conservation, Hamburg, Germany 8Instituto de Neuroetología, Universidad Veracruzana, Veracruz, México 9Conservation International Colombia, Bogotá, DC, Colombia 10Abteilung Verhaltensforschung & Ökologie, Deutsches Primatenzentrum, Göttingen, Germany 11Fundação Parque Zoológico de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil 12The Nature Conservancy, China Program, Kunming, Yunnan, China 13Conservation International Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia 14 Gene Bank of Primates, Deutsches Primatenzentrum, Göttingen, Germany 15Zoo Outreach Organisation, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India Introduction among primatologists working in the field who had first-hand knowledge of the causes of threats to primates, both in gen- Here we report on the fourth iteration of the biennial eral and in particular with the species or communities they listing of a consensus of 25 primate species considered to study. The meeting and the review of the list of the World’s be amongst the most endangered worldwide and the most in 25 Most Endangered Primates resulted in its official endorse- need of urgent conservation measures. -

(West-Sumatra, Indonesia) Towards Primate Hunting and Conse

:ŽƵƌŶĂůŽĨdŚƌĞĂƚĞŶĞĚdĂdžĂͮǁǁǁ͘ƚŚƌĞĂƚĞŶĞĚƚĂdžĂ͘ŽƌŐͮϮϲKĐƚŽďĞƌϮϬϭϰͮϲ;ϭϭͿ͗ϲϯϴϵʹϲϯϵϴ Ù㮽 <ÄÊó½¦͕ãã®ãçÝÄÖÙã®ÝÊ¥½Ê½ÖÊÖ½ÊÄ ^®Ùçã/ݽÄ;tÝãͲ^çÃãÙ͕/ÄÊÄÝ®ͿãÊóÙÝÖÙ®Ãã «çÄã®Ä¦ÄÊÄÝÙòã®ÊÄ /^^EϬϵϳϰͲϳϵϬϳ;KŶůŝŶĞͿ /^^EϬϵϳϰͲϳϴϵϯ;WƌŝŶƚͿ DĂƌĐĞůYƵŝŶƚĞŶϭ͕&ĂƌƋƵŚĂƌ^ƟƌůŝŶŐϮ͕^ƚĞĨĂŶ^ĐŚǁĂƌnjĞϯ͕zŽĂŶŝŶĂƚĂϰΘ<ĞŝƚŚ,ŽĚŐĞƐϱ 1,5 ZĞƉƌŽĚƵĐƟǀĞŝŽůŽŐLJhŶŝƚ͕'ĞƌŵĂŶWƌŝŵĂƚĞĞŶƚĞƌ͕'ŽĞƫŶŐĞŶϯϳϬϳϳ͕'ĞƌŵĂŶLJ KWE^^ 1,5 ^ŝďĞƌƵƚŽŶƐĞƌǀĂƟŽŶWƌŽŐƌĂŵŵĞ͕WŽůĂDĂƐ͕WĂĚĂŶŐϮϱϭϮϮ͕/ŶĚŽŶĞƐŝĂ Ϯ͕ϰ&ĂƵŶĂΘ&ůŽƌĂ/ŶƚĞƌŶĂƟŽŶĂů͕/ŶĚŽŶĞƐŝĂWƌŽŐƌĂŵŵĞ͕:ĂŬĂƌƚĂϭϮϱϱϬ͕/ŶĚŽŶĞƐŝĂ ϯĞƉĂƌƚŵĞŶƚŽĨŐƌŝĐƵůƚƵƌĂůĐŽŶŽŵŝĐƐĂŶĚZƵƌĂůĞǀĞůŽƉŵĞŶƚ͕hŶŝǀĞƌƐŝƚLJŽĨ'ŽĞƫŶŐĞŶ͕'ŽĞƫŶŐĞŶϯϳϬϳϯ͕'ĞƌŵĂŶLJ 1ŵĂƌĐĞů͘ƋƵŝŶƚĞŶͲĚƉnjΛŐŵdž͘ĚĞ;ĐŽƌƌĞƐƉŽŶĚŝŶŐĂƵƚŚŽƌͿ͕ϮĨ͘ƐƟƌůŝŶŐϰϵΛŐŵĂŝů͘ĐŽŵ͕ ϯƐ͘ƐĐŚǁĂƌnjĞΛĂŐƌ͘ƵŶŝͲŐŽĞƫŶŐĞŶ͘ĚĞ͕ϰLJŽĂŶϳĚŝŶĂƚĂΛŐŵĂŝů͘ĐŽŵ͕5ŬŚŽĚŐĞƐΛĚƉnj͘ĞƵ ďƐƚƌĂĐƚ͗dŚĞDĞŶƚĂǁĂŝƌĐŚŝƉĞůĂŐŽ;tĞƐƚͲ^ƵŵĂƚƌĂ͕/ŶĚŽŶĞƐŝĂͿŚĂƌďŽƵƌƐĂǁĞĂůƚŚŽĨĞŶĚĞŵŝĐĂŶŝŵĂůƐĂŶĚƉůĂŶƚƐŝŶĐůƵĚŝŶŐƐŝdžƵŶŝƋƵĞ ƉƌŝŵĂƚĞƐƉĞĐŝĞƐ͕ĂůůƚŚƌĞĂƚĞŶĞĚďLJŚĂďŝƚĂƚůŽƐƐĂŶĚŚƵŶƟŶŐ͘ůƚŚŽƵŐŚŚƵŶƟŶŐŝƐŬŶŽǁŶƚŽďĞǁŝĚĞƐƉƌĞĂĚ͕ůŝƩůĞƐLJƐƚĞŵĂƟĐǁŽƌŬŚĂƐďĞĞŶ ĐĂƌƌŝĞĚŽƵƚƚŽĞdžĂŵŝŶĞŝƚƐƐĐĂůĞĂŶĚŝŵƉĂĐƚŽŶDĞŶƚĂǁĂŝDzƐƉƌŝŵĂƚĞƉŽƉƵůĂƟŽŶƐ͘,ĞƌĞǁĞƌĞƉŽƌƚĂŶŝƐůĂŶĚͲǁŝĚĞƐƵƌǀĞLJĐĂƌƌŝĞĚŽƵƚŽŶ ^ŝďĞƌƵƚ͕ƚŚĞĂƌĐŚŝƉĞůĂŐŽ͛ƐůĂƌŐĞƐƚŝƐůĂŶĚ͕ƚŽĂƐƐĞƐƐŚƵŶƟŶŐďĞŚĂǀŝŽƵƌǁŝƚŚƌĞƐƉĞĐƚƚŽƚŚĞĨŽƵƌůŽĐĂůůLJͲŽĐĐƵƌƌŝŶŐƉƌŝŵĂƚĞƐƉĞĐŝĞƐ͕ĂƐǁĞůůĂƐ ƚŚĞĂƫƚƵĚĞƐŽĨŝŶĚŝŐĞŶŽƵƐŝŶŚĂďŝƚĂŶƚƐƚŽƌĞƐŽƵƌĐĞƵƟůŝnjĂƟŽŶ͘&ĂĐĞͲƚŽͲĨĂĐĞŝŶƚĞƌǀŝĞǁƐǁĞƌĞĐŽŶĚƵĐƚĞĚŝŶŵŝĚͲϮϬϭϮǁŝƚŚϯϵϬƌĞƐƉŽŶĚĞŶƚƐ ĨƌŽŵϱϬǀŝůůĂŐĞƐƵƐŝŶŐĂƐƚƌƵĐƚƵƌĞĚƋƵĞƐƟŽŶŶĂŝƌĞ͘KǀĞƌĂůů͕ĐĂ͘ŽŶĞƋƵĂƌƚĞƌŽĨƚŚĞƌĞƐƉŽŶĚĞŶƚƐ;ϮϰйͿĂƌĞƐƟůůĂĐƟǀĞŚƵŶƚĞƌƐ͕ŐĞŶĞƌĂůůLJ ƚĂƌŐĞƟŶŐ Simias concolor;ϳϳйͿ͕Macaca siberu;ϳϭйͿĂŶĚWƌĞƐďLJƟƐƐŝďĞƌƵ;ϲϴйͿ͖Hylobates klossiiŝƐƌĂƌĞůLJŚƵŶƚĞĚ;ϯйͿ͘DŽƐƚůLJ͕ĂƐŝŶŐůĞ ĂŶŝŵĂůŝƐĐĂƉƚƵƌĞĚƉĞƌŚƵŶƚ͕ǁŝƚŚĂǀĞƌĂŐĞŶƵŵďĞƌƐƉĞƌƚŚƌĞĞŵŽŶƚŚƐƌĂŶŐŝŶŐĨƌŽŵϭ͘ϵʹϮ͘ϯŝŶĚŝǀŝĚƵĂůƐ;ĨŽƌS. -

Biological Richness of Gunung Slamet, Central Java, and the Need for Its Protection

Biological richness of Gunung Slamet, Central Java, and the need for its protection C HRISTIAN D EVENISH,ACHMAD R IDHA J UNAID,ANDRIANSYAH,RIA S ARYANTHI S. (BAS) VAN B ALEN,FAJAR K APRAWI,GANJAR C AHYO A PRIANTO R ICHARD C. STANLEY,OLIVER P OOLE,ANDREW O WEN N. J. COLLAR and S TUART J. MARSDEN Abstract Designating protected areas remains a core strategy we discuss different options for improving the protection in biodiversity conservation. Despite high endemism, mon- status of Gunung Slamet, including designation as a tane forests across the island of Java are under-represented National Park or Essential Ecosystem. in Indonesia’s protected area network. Here, we document Keywords Conservation planning, Garrulax rufifrons the montane biodiversity of Gunung Slamet, an isolated slamatensis, Gunung Slamet, Hylobates moloch, Indonesia, volcano in Central Java, and provide evidence to support Java, species distribution models, threatened species its increased protection. During September–December , we surveyed multiple sites for birds, primates, terrestrial Supplementary material for this article is available at mammals, reptiles, amphibians and vegetation. Survey doi.org/./S methods included transects, camera traps and targeted searches at six sites, at altitudes of –, m. We used species distribution models for birds and mammals of con- servation concern to identify priority areas for protection. Introduction We recorded bird species ( globally threatened), n the face of the current global extinction crisis mammals (five globally threatened) and reptiles and I(Bradshaw et al., ; Ceballos et al., ), it is vital amphibians (two endemic). Our species distribution models to establish protected areas that can serve as biological reser- showed considerable cross-taxon congruence between im- voirs for species and ecological processes (Chape et al., ; ’ portant areas on Slamet s upper slopes, generally above Jenkins & Joppa, ; Le Saout et al., ; Venter et al., , m. -

Primate Research and Conservation in Malaysia

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by The University of North Carolina at Greensboro Archived version from NCDOCKS Institutional Repository http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/asu/ Primate Research And Conservation In Malaysia By: Susan Lappan and Nadine Ruppert Abstract Malaysia is inhabited by ≥25 nonhuman primate species from five families, one of the most diverse primate faunas on earth. Unfortunately, most Malaysian primates are threatened with extinction due to habitat loss, degradation, and fragmentation, hunting and the synergies among these processes. Here, we review research on primates and issues related to their conservation in Malaysia. Despite the charisma and cultural importance of primates, the importance of primates in ecological processes such as seed dispersal, and the robust development of biodiversity- related sciences in Malaysia, relatively little research specifically focused on wild primates has been conducted in Malaysia since the 1980s. Forest clearing for plantation agriculture has been a primary driver of forest loss and fragmentation in Malaysia. Selective logging also has primarily negative impacts on primates, but these impacts vary across primate taxa, and previously-logged forests are important habitats for many Malaysian primates. Malaysia is crossed by a dense road network, which fragments primate habitats, facilitates further human encroachment into forested areas and causes substantial mortality due to road kills. Primates in Malaysia are hunted for food or as pests, trapped for translocation due to wildlife-human conflict and hunted and trapped for illegal trade as pets. Further research on the distribution, abundance, ecology and behavioural biology of Malaysian primates is needed to inform effective management plans. -

1 Classification of Nonhuman Primates

BLBS036-Voevodin April 8, 2009 13:57 Part I: Introduction to Primatology and Virology COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL BLBS036-Voevodin April 8, 2009 13:57 BLBS036-Voevodin April 8, 2009 13:57 1 Classification of Nonhuman Primates 1.1 Introduction that the animals colloquially known as monkeys and 1.2 Classification and nomenclature of primates apes are primates. From the zoological standpoint, hu- 1.2.1 Higher primate taxa (suborder, infraorder, mans are also apes, although the use of this term is parvorder, superfamily) usually restricted to chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, 1.2.2 Molecular taxonomy and molecular and gibbons. identification of nonhuman primates 1.3 Old World monkeys 1.2. CLASSIFICATION AND NOMENCLATURE 1.3.1 Guenons and allies OF PRIMATES 1.3.1.1 African green monkeys The classification of primates, as with any zoological 1.3.1.2 Other guenons classification, is a hierarchical system of taxa (singu- 1.3.2 Baboons and allies lar form—taxon). The primate taxa are ranked in the 1.3.2.1 Baboons and geladas following descending order: 1.3.2.2 Mandrills and drills 1.3.2.3 Mangabeys Order 1.3.3 Macaques Suborder 1.3.4 Colobines Infraorder 1.4 Apes Parvorder 1.4.1 Lesser apes (gibbons and siamangs) Superfamily 1.4.2 Great apes (chimpanzees, gorillas, and Family orangutans) Subfamily 1.5 New World monkeys Tribe 1.5.1 Marmosets and tamarins Genus 1.5.2 Capuchins, owl, and squirrel monkeys Species 1.5.3 Howlers, muriquis, spider, and woolly Subspecies monkeys Species is the “elementary unit” of biodiversity.