The World's 25 Most Endangered Primates, 2006-2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan Paniscus)

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Editors: Dr Jeroen Stevens Contact information: Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp – K. Astridplein 26 – B 2018 Antwerp, Belgium Email: [email protected] Name of TAG: Great Ape TAG TAG Chair: Dr. María Teresa Abelló Poveda – Barcelona Zoo [email protected] Edition: First edition - 2020 1 2 EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (February 2020) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA APE TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

10 Sota3 Chapter 7 REV11

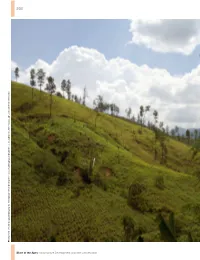

200 Until recently, quantifying rates of tropical forest destruction was challenging and laborious. © Jabruson 2017 (www.jabruson.photoshelter.com) forest quantifying rates of tropical Until recently, Photo: State of the Apes Infrastructure Development and Ape Conservation 201 CHAPTER 7 Mapping Change in Ape Habitats: Forest Status, Loss, Protection and Future Risk Introduction This chapter examines the status of forested habitats used by apes, charismatic species that are almost exclusively forest-dependent. With one exception, the eastern hoolock, all ape species and their subspecies are classi- fied as endangered or critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (IUCN, 2016c). Since apes require access to forested or wooded land- scapes, habitat loss represents a major cause of population decline, as does hunting in these settings (Geissmann, 2007; Hickey et al., 2013; Plumptre et al., 2016b; Stokes et al., 2010; Wich et al., 2008). Until recently, quantifying rates of trop- ical forest destruction was challenging and laborious, requiring advanced technical Chapter 7 Status of Apes 202 skills and the analysis of hundreds of satel- for all ape subspecies (Geissmann, 2007; lite images at a time (Gaveau, Wandono Tranquilli et al., 2012; Wich et al., 2008). and Setiabudi, 2007; LaPorte et al., 2007). In addition, the chapter projects future A new platform, Global Forest Watch habitat loss rates for each subspecies and (GFW), has revolutionized the use of satel- uses these results as one measure of threat lite imagery, enabling the first in-depth to their long-term survival. GFW’s new analysis of changes in forest availability in online forest monitoring and alert system, the ranges of 22 great ape and gibbon spe- entitled Global Land Analysis and Dis- cies, totaling 38 subspecies (GFW, 2014; covery (GLAD) alerts, combines cutting- Hansen et al., 2013; IUCN, 2016c; Max Planck edge algorithms, satellite technology and Insti tute, n.d.-b). -

Body Measurements for the Monkeys of Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea

Primate Conservation 2009 (24): 99–105 Body Measurements for the Monkeys of Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea Thomas M. Butynski¹,², Yvonne A. de Jong² and Gail W. Hearn¹ ¹Bioko Biodiversity Protection Program, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA ²Eastern Africa Primate Diversity and Conservation Program, Nanyuki, Kenya Abstract: Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea, has a rich (eight genera, 11 species), unique (seven endemic subspecies), and threat- ened (five species) primate fauna, but the taxonomic status of most forms is not clear. This uncertainty is a serious problem for the setting of priorities for the conservation of Bioko’s (and the region’s) primates. Some of the questions related to the taxonomic status of Bioko’s primates can be resolved through the statistical comparison of data on their body measurements with those of their counterparts on the African mainland. Data for such comparisons are, however, lacking. This note presents the first large set of body measurement data for each of the seven species of monkeys endemic to Bioko; means, ranges, standard deviations and sample sizes for seven body measurements. These 49 data sets derive from 544 fresh adult specimens (235 adult males and 309 adult females) collected by shotgun hunters for sale in the bushmeat market in Malabo. Key Words: Bioko Island, body measurements, conservation, monkeys, morphology, taxonomy Introduction gordonorum), and surprisingly few such data exist even for some of the more widespread species (for example, Allen’s Comparing external body measurements for adult indi- swamp monkey Allenopithecus nigroviridis, northern tala- viduals from different sites has long been used as a tool for poin monkey Miopithecus ogouensis, and grivet Chlorocebus describing populations, subspecies, and species of animals aethiops). -

Gibbon Classification : the Issue of Species and Subspecies

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1988 Gibbon classification : the issue of species and subspecies Erin Lee Osterud Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons, and the Genetics and Genomics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Osterud, Erin Lee, "Gibbon classification : the issue of species and subspecies" (1988). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3925. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5809 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Erin Lee Osterud for the Master of Arts in Anthropology presented July 18, 1988. Title: Gibbon Classification: The Issue of Species and Subspecies. APPROVED BY MEM~ OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Marc R. Feldesman, Chairman Gibbon classification at the species and subspecies levels has been hotly debated for the last 200 years. This thesis explores the reasons for this debate. Authorities agree that siamang, concolor, kloss and hoolock are species, while there is complete lack of agreement on lar, agile, moloch, Mueller's and pileated. The disagreement results from the use and emphasis of different character traits, and from debate on the occurrence and importance of gene flow. GIBBON CLASSIFICATION: THE ISSUE OF SPECIES AND SUBSPECIES by ERIN LEE OSTERUD A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ANTHROPOLOGY Portland State University 1989 TO THE OFFICE OF GRADUATE STUDIES: The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Erin Lee Osterud presented July 18, 1988. -

Primates of the Southern Mentawai Islands

Primate Conservation 2018 (32): 193-203 The Status of Primates in the Southern Mentawai Islands, Indonesia Ahmad Yanuar1 and Jatna Supriatna2 1Department of Biology and Post-graduate Program in Biology Conservation, Tropical Biodiversity Conservation Center- Universitas Nasional, Jl. RM. Harsono, Jakarta, Indonesia 2Department of Biology, FMIPA and Research Center for Climate Change, University of Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia Abstract: Populations of the primates native to the Mentawai Islands—Kloss’ gibbon Hylobates klossii, the Mentawai langur Presbytis potenziani, the Mentawai pig-tailed macaque Macaca pagensis, and the snub-nosed pig-tailed monkey Simias con- color—persist in disturbed and undisturbed forests and forest patches in Sipora, North Pagai and South Pagai. We used the line-transect method to survey primates in Sipora and the Pagai Islands and estimate their population densities. We walked 157.5 km and 185.6 km of line transects on Sipora and on the Pagai Islands, respectively, and obtained 93 sightings on Sipora and 109 sightings on the Pagai Islands. On Sipora, we estimated population densities for H. klossii, P. potenziani, and S. concolor in an area of 9.5 km², and M. pagensis in an area of 12.6 km². On the Pagai Islands, we estimated the population densities of the four primates in an area of 11.1 km². Simias concolor was found to have the lowest group densities on Sipora, whilst P. potenziani had the highest group densities. On the Pagai Islands, H. klossii was the least abundant and M. pagensis had the highest group densities. Primate populations, notably of the snub-nosed pig-tailed monkey and Kloss’ gibbon, are reduced and threatened on the southern Mentawai Islands. -

Controlled Animals

Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Policy Division Controlled Animals Wildlife Regulation, Schedule 5, Part 1-4: Controlled Animals Subject to the Wildlife Act, a person must not be in possession of a wildlife or controlled animal unless authorized by a permit to do so, the animal was lawfully acquired, was lawfully exported from a jurisdiction outside of Alberta and was lawfully imported into Alberta. NOTES: 1 Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column. 2 Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule. 3 This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal. Part 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 1. AMERICAN OPOSSUMS (Family Didelphidae) Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana 2. SHREWS (Family Soricidae) Long-tailed Shrews Genus Sorex Arboreal Brown-toothed Shrew Episoriculus macrurus North American Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Old World Water Shrews Genus Neomys Ussuri White-toothed Shrew Crocidura lasiura Greater White-toothed Shrew Crocidura russula Siberian Shrew Crocidura sibirica Piebald Shrew Diplomesodon pulchellum 3. -

7 Gibbon Song and Human Music from An

Gibbon Song and Human Music from an 7 Evolutionary Perspective Thomas Geissmann Abstract Gibbons (Hylobates spp.) produce loud and long song bouts that are mostly exhibited by mated pairs. Typically, mates combine their partly sex-specific repertoire in relatively rigid, precisely timed, and complex vocal interactions to produce well-patterned duets. A cross-species comparison reveals that singing behavior evolved several times independently in the order of primates. Most likely, loud calls were the substrate from which singing evolved in each line. Structural and behavioral similarities suggest that, of all vocalizations produced by nonhuman primates, loud calls of Old World monkeys and apes are the most likely candidates for models of a precursor of human singing and, thus, human music. Sad the calls of the gibbons at the three gorges of Pa-tung; After three calls in the night, tears wet the [traveler's] dress. (Chinese song, 4th century, cited in Van Gulik 1967, p. 46). Of the gibbons or lesser apes, Owen (1868) wrote: “... they alone, of brute Mammals, may be said to sing.” Although a few other mammals are known to produce songlike vocalizations, gibbons are among the few mammals whose vocalizations elicit an emotional response from human listeners, as documented in the epigraph. The interesting questions, when comparing gibbon and human singing, are: do similarities between gibbon and human singing help us to reconstruct the evolution of human music (especially singing)? and are these similarities pure coincidence, analogous features developed through convergent evolution under similar selective pressures, or the result of evolution from common ancestral characteristics? To my knowledge, these questions have never been seriously assessed. -

Online Appendix for “The Impact of the “World's 25 Most Endangered

Online appendix for “The impact of the “World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates” list on scientific publications and media” Table A1. List of species included in the Top25 most endangered primate list from the list of 2000-2002 to 2010-2012 and used in the scientific publication analysis. There is the year of their first mention in the Top25 list and the consecutive mentions in the following Top25 lists. Species names are the current species names (based on IUCN) and not the name used at the time of the Top25 list release. First Second Third Fourth Fifth Sixth Species mention mention mention mention mention mention Ateles fusciceps 2006 Ateles hybridus 2006 2008 2010 Ateles hybridus brunneus 2004 Brachyteles hypoxanthus 2000 2002 2004 Callicebus barbarabrownae 2010 Cebus flavius 2010 Cebus xanthosternos 2000 2002 2004 Cercocebus atys lunulatus 2000 2002 2004 Cercocebus galeritus galeritus 2002 Cercocebus sanjei 2000 2002 2004 Cercopithecus roloway 2002 2006 2008 2010 Cercopithecus sclateri 2000 Eulemur cinereiceps 2004 2006 2008 Eulemur flavifrons 2008 2010 Galagoides rondoensis 2006 2008 2010 Gorilla beringei graueri 2010 Gorilla beringei beringei 2000 2002 2004 Gorilla gorilla diehli 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 Hapalemur aureus 2000 Hapalemur griseus alaotrensis 2000 Hoolock hoolock 2006 2008 Hylobates moloch 2000 Lagothrix flavicauda 2000 2006 2008 2010 Leontopithecus caissara 2000 2002 2004 Leontopithecus chrysopygus 2000 Leontopithecus rosalia 2000 Lepilemur sahamalazensis 2006 Lepilemur septentrionalis 2008 2010 Loris tardigradus nycticeboides -

Proposal for Inclusion of the Chimpanzee

CMS Distribution: General CONVENTION ON MIGRATORY UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.1 25 May 2017 SPECIES Original: English 12th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Manila, Philippines, 23 - 28 October 2017 Agenda Item 25.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF THE CHIMPANZEE (Pan troglodytes) ON APPENDIX I AND II OF THE CONVENTION Summary: The Governments of Congo and the United Republic of Tanzania have jointly submitted the attached proposal* for the inclusion of the Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) on Appendix I and II of CMS. *The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CMS Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF CHIMPANZEE (Pan troglodytes) ON APPENDICES I AND II OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS A: PROPOSAL Inclusion of Pan troglodytes in Appendix I and II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. B: PROPONENTS: Congo and the United Republic of Tanzania C: SUPPORTING STATEMENT 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class: Mammalia 1.2 Order: Primates 1.3 Family: Hominidae 1.4 Genus, species or subspecies, including author and year: Pan troglodytes (Blumenbach 1775) (Wilson & Reeder 2005) [Note: Pan troglodytes is understood in the sense of Wilson and Reeder (2005), the current reference for terrestrial mammals used by CMS). -

Colobus Angolensis Palliatus) in an East African Coastal Forest

African Primates 7 (2): 203-210 (2012) Activity Budgets of Peters’ Angola Black-and-White Colobus (Colobus angolensis palliatus) in an East African Coastal Forest Zeno Wijtten1, Emma Hankinson1, Timothy Pellissier2, Matthew Nuttall1 & Richard Lemarkat3 1Global Vision International (GVI) Kenya 2University of Winnipeg, Winnipeg, Canada 3Kenyan Wildlife Services (KWS), Kenya Abstract: Activity budgets of primates are commonly associated with strategies of energy conservation and are affected by a range of variables. In order to establish a solid basis for studies of colobine monkey food preference, food availability, group size, competition and movement, and also to aid conservation efforts, we studied activity of individuals from social groups of Colobus angolensis palliatus in a coastal forest patch in southeastern Kenya. Our observations (N = 461 hours) were conducted year-round, over a period of three years. In our Colobus angolensis palliatus study population, there was a relatively low mean group size of 5.6 ± SD 2.7. Resting, feeding, moving and socializing took up 64%, 22%, 3% and 4% of their time, respectively. In the dry season, as opposed to the wet season, the colobus increased the time they spent feeding, traveling, and being alert, and decreased the time they spent resting. General activity levels and group sizes are low compared to those for other populations of Colobus spp. We suggest that Peters’ Angola black-and-white colobus often live (including at our study site) under low preferred-food availability conditions and, as a result, are adapted to lower activity levels. With East African coastal forest declining rapidly, comparative studies focusing on C. -

World's Most Endangered Primates

Primates in Peril The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018 Edited by Christoph Schwitzer, Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands, Federica Chiozza, Elizabeth A. Williamson, Elizabeth J. Macfie, Janette Wallis and Alison Cotton Illustrations by Stephen D. Nash IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG) International Primatological Society (IPS) Conservation International (CI) Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Published by: IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Copyright: ©2017 Conservation International All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Inquiries to the publisher should be directed to the following address: Russell A. Mittermeier, Chair, IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, VA 22202, USA. Citation (report): Schwitzer, C., Mittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B., Chiozza, F., Williamson, E.A., Macfie, E.J., Wallis, J. and Cotton, A. (eds.). 2017. Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA. 99 pp. Citation (species): Salmona, J., Patel, E.R., Chikhi, L. and Banks, M.A. 2017. Propithecus perrieri (Lavauden, 1931). In: C. Schwitzer, R.A. Mittermeier, A.B. Rylands, F. Chiozza, E.A. Williamson, E.J. Macfie, J. Wallis and A. Cotton (eds.), Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018, pp. 40-43. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA. -

Mandrillus Leucophaeus Poensis)

Ecology and Behavior of the Bioko Island Drill (Mandrillus leucophaeus poensis) A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Jacob Robert Owens in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2013 i © Copyright 2013 Jacob Robert Owens. All Rights Reserved ii Dedications To my wife, Jen. iii Acknowledgments The research presented herein was made possible by the financial support provided by Primate Conservation Inc., ExxonMobil Foundation, Mobil Equatorial Guinea, Inc., Margo Marsh Biodiversity Fund, and the Los Angeles Zoo. I would also like to express my gratitude to Dr. Teck-Kah Lim and the Drexel University Office of Graduate Studies for the Dissertation Fellowship and the invaluable time it provided me during the writing process. I thank the Government of Equatorial Guinea, the Ministry of Fisheries and the Environment, Ministry of Information, Press, and Radio, and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism for the opportunity to work and live in one of the most beautiful and unique places in the world. I am grateful to the faculty and staff of the National University of Equatorial Guinea who helped me navigate the geographic and bureaucratic landscape of Bioko Island. I would especially like to thank Jose Manuel Esara Echube, Claudio Posa Bohome, Maximilliano Fero Meñe, Eusebio Ondo Nguema, and Mariano Obama Bibang. The journey to my Ph.D. has been considerably more taxing than I expected, and I would not have been able to complete it without the assistance of an expansive list of people. I would like to thank all of you who have helped me through this process, many of whom I lack the space to do so specifically here.