Ontogeny of Positional Behavior in Captive Silvered Langurs (Trachypithecus Cristatus)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keshav Ravi by Keshav Ravi

by Keshav Ravi by Keshav Ravi Preface About the Author In the whole world, there are more than 30,000 species Keshav Ravi is a caring and compassionate third grader threatened with extinction today. One prominent way to who has been fascinated by nature throughout his raise awareness as to the plight of these animals is, of childhood. Keshav is a prolific reader and writer of course, education. nonfiction and is always eager to share what he has learned with others. I have always been interested in wildlife, from extinct dinosaurs to the lemurs of Madagascar. At my ninth Outside of his family, Keshav is thrilled to have birthday, one personal writing project I had going was on the support of invested animal advocates, such as endangered wildlife, and I had chosen to focus on India, Carole Hyde and Leonor Delgado, at the Palo Alto the country where I had spent a few summers, away from Humane Society. my home in California. Keshav also wishes to thank Ernest P. Walker’s Just as I began to explore the International Union for encyclopedia (Walker et al. 1975) Mammals of the World Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List species for for inspiration and the many Indian wildlife scientists India, I realized quickly that the severity of threat to a and photographers whose efforts have made this variety of species was immense. It was humbling to then work possible. realize that I would have to narrow my focus further down to a subset of species—and that brought me to this book on the Endangered Mammals of India. -

Nonhuman Primates

Zoological Studies 42(1): 93-105 (2003) Dental Variation among Asian Colobines (Nonhuman Primates): Phylogenetic Similarities or Functional Correspondence? Ruliang Pan1,2,* and Charles Oxnard1 1School of Anatomy and Human Biology, University of Western Australia, Crawley, Perth, WA 6009, Australia 2Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100080, China (Accepted August 27, 2002) Ruliang Pan and Charles Oxnard (2003) Dental variation among Asian colobines (nonhuman primates): phy- logenetic similarities or functional correspondence? Zoological Studies 42(1): 93-105. In order to reveal varia- tions among Asian colobines and to test whether the resemblance in dental structure among them is mainly associated with similarities in phylogeny or functional adaptation, teeth of 184 specimens from 15 Asian colobine species were measured and studied by performing bivariate (allometry) and multivariate (principal components) analyses. Results indicate that each tooth shows a significant close relationship with body size. Low negative and positive allometric scales for incisors and molars (M2s and M3s), respectively, are each con- sidered to be related to special dental modifications for folivorous preference of colobines. Sexual dimorphism in canine eruption reported by Harvati (2000) is further considered to be associated with differences in growth trajectories (allometric pattern) between the 2 sexes. The relationships among the 6 genera of Asian colobines found greatly differ from those proposed in other studies. Four groups were detected: 1) Rhinopithecus, 2) Semnopithecus, 3) Trachypithecus, and 4) Nasalis, Pygathrix, and Presbytis. These separations were mainly determined by differences in molar structure. Molar sizes of the former 2 groups are larger than those of the latter 2 groups. -

Interim Report

Interim Report Distribution, ecology and habitat use of the Himalayan gray langur Semnopithecus ajax in Jammu and Kashmir, India. Background Himalayan gray langur, Semnopithecus ajax, is considered endangered due to its endemicity to Himalayan region and its declining population size (Groves and Molur, 2008). This primate was formerly considered a subspecies of Semnopithecus entellus (Brandon-Jones 2004, Brandon-Jones and others 2004; and Napier 1985). However, recent studies confirm its status as a species, Semnopithecus ajax (Groves 2001; Ashalakshmi 2015). Due to pre- existing confusion in taxonomy, its current distribution and conservation status are poorly understood. An assessment of (1) geographical distribution and population status, (2) conservation status, and (3) habitat use and feeding ecology are the need of the hour to develop conservation action plans for this species, across its natural range. The very first sighting record of this species was likely from Sikkim at 2700m in 1855 (Hooker 1855). Later it has been recorded in various other parts of Himalayas, e.g., in Nepal (Bishop 1975), Himachal Pradesh (Sugiyama 1976), Pakistan (Roberts 1997) and Kashmir (Lawrence 1895; Brandon-Jones 2004; Molur 2008). In this study, I propose to assess the geographical distribution, status, habitat use and feeding ecology of Himalayan gray langur in Kashmir. Kashmir (32° N, 72° E; Jammu & Kashmir state), in north western India, is an oval-shaped valley surrounded with a chain of mountains ranging from 1600m to 5000m and above. The valley has a mix of forests, orchards, croplands, and human habitation. Due to altitudinal variation, there is variation in temperature and vegetation type. -

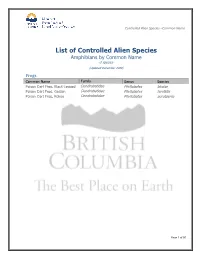

Controlled Alien Species -Common Name

Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Amphibians by Common Name -3 species- (Updated December 2009) Frogs Common Name Family Genus Species Poison Dart Frog, Black-Legged Dendrobatidae Phyllobates bicolor Poison Dart Frog, Golden Dendrobatidae Phyllobates terribilis Poison Dart Frog, Kokoe Dendrobatidae Phyllobates aurotaenia Page 1 of 50 Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Birds by Common Name -3 species- (Updated December 2009) Birds Common Name Family Genus Species Cassowary, Dwarf Cassuariidae Casuarius bennetti Cassowary, Northern Cassuariidae Casuarius unappendiculatus Cassowary, Southern Cassuariidae Casuarius casuarius Page 2 of 50 Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Mammals by Common Name -437 species- (Updated March 2010) Common Name Family Genus Species Artiodactyla (Even-toed Ungulates) Bovines Buffalo, African Bovidae Syncerus caffer Gaur Bovidae Bos frontalis Girrafe Giraffe Giraffidae Giraffa camelopardalis Hippopotami Hippopotamus Hippopotamidae Hippopotamus amphibious Hippopotamus, Madagascan Pygmy Hippopotamidae Hexaprotodon liberiensis Carnivora Canidae (Dog-like) Coyote, Jackals & Wolves Coyote (not native to BC) Canidae Canis latrans Dingo Canidae Canis lupus Jackal, Black-Backed Canidae Canis mesomelas Jackal, Golden Canidae Canis aureus Jackal Side-Striped Canidae Canis adustus Wolf, Gray (not native to BC) Canidae Canis lupus Wolf, Maned Canidae Chrysocyon rachyurus Wolf, Red Canidae Canis rufus Wolf, Ethiopian -

2007 Primate Teacher

Guide to South Asian Primates for Teachers and Students of All Ages Lorises Langurs Macaques Gibbons Compiled and Edited by Sally Walker and Sanjay Molur Illustrations by Stephen Nash Guide to South Asian Primates for Teachers and Students of All Ages Sally Walker & Sanjay Molur (Compilers & Editors) Compiled from Status of South Asian Primates. Report of the Conservation Assessment and Management Plan CAMP Workshop 2003, recent notes on primates taxonomy from several sources and practical action suggestion for kids Published by: Zoo Outreach Organisation and Primate Specialist Group – South Asia in collaboration with Wildlife Information & Liaison Development Society Copyright:© Zoo Outreach Organisation 2007 This publication can be reproduced for educational and non-commercial purposes without prior permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior permission (in writing) of the copyright holder. ISBN: 81-88722-20-0 Citation: Walker, S. & S. Molur (Compilers & Editors) 2007. Guide to South Asian Primates for Teachers and Students of All Ages. Zoo Outreach Organisation, PSG South Asia and WILD, Coimbatore, India. Illustrations by: Stephen Nash Sponsored by: Margot Marsh Biodiversity Foundation Primate Action Fund/ Conservation International Compiled by: Sally Walker and Sanjay Molur from the book Molur et al. (2003). Status of South Asian Primates, Report of the Conservation Assessment and Management Plan CAMP Workshop, Coimbatore, 2003 Proofreading by: R. Marimuthu; Typesetting by: Latha Ravikumar The international boundaries of India reproduced in this book are neither purported to be correct nor authentic by the Survey of India directives. -

The Placenta of the Colobinae Nghi™N C¯U V“ Nhau Thai Còa Nh„M Khÿ

Vietnamese Journal of Primatology (2008) 2, 33-39 The placenta of the Colobinae Kurt Benirschke University of California San Diego, Department of Pathology, USA 8457 Prestwick Drive La Jolla, CA 92037, USA <[email protected]> Key words: Colobinae, langurs, placenta, bilobed, hemochorial Summary Leaf-eating monkeys have a hemomonochorial placenta that is usually composed of two lobes and these are connected by large fetal vessels. In general, the placenta is similar to that of the rhesus monkey ( Macaca mulatta ) and, like that species, occasional placentas possess only a single lobe. This paper describes the structure, weights and cord lengths of all colobine monkeys examined by the author to date and it provides an overview of the placentation of langurs in general. Nghi™n c¯u v“ nhau thai cÒa nh„m khÿ ®n l∏ T„m tæt ô nh„m khÿ ®n l∏ (leaf-eating monkeys) nhau thai th≠Íng Æ≠Óc tπo bÎi hai thÔy, vµ hai thÔy nµy nËi vÌi nhau bÎi nh˜ng mπch m∏u lÌn tı bµo thai. Nh◊n chung, c†u tπo nhau thai cÒa nh„m nµy giËng Î nh„m khÿ vµng (Macaca mulatta ). Vµ cÚng nh≠ Î khÿ vµng, thÿnh tho∂ng nhau thai chÿ c„ mÈt thÔy. Trong nghi™n c¯u nµy t∏c gi∂ m´ t∂ c†u tπo, c©n n∆ng cÚng nh≠ chi“u dµi nhau thai cÒa c∏c loµi thuÈc nh„m khÿ ®n l∏. Qua Æ„ cung c†p th´ng tin toµn di÷n v“ c†u tπo nhau thai cÒa c∏c loµi khÿ ®n l∏. -

OPTIMAL FORAGING on the ROOF of the WORLD: a FIELD STUDY of HIMALAYAN LANGURS a Dissertation Submitted to Kent State University

OPTIMAL FORAGING ON THE ROOF OF THE WORLD: A FIELD STUDY OF HIMALAYAN LANGURS A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Kenneth A. Sayers May 2008 Dissertation written by Kenneth A. Sayers B.A., Anderson University, 1996 M.A., Kent State University, 1999 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2008 Approved by ____________________________________, Dr. Marilyn A. Norconk Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee ____________________________________, Dr. C. Owen Lovejoy Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee ____________________________________, Dr. Richard S. Meindl Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee ____________________________________, Dr. Charles R. Menzel Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Accepted by ____________________________________, Dr. Robert V. Dorman Director, School of Biomedical Sciences ____________________________________, Dr. John R. D. Stalvey Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................... viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .....................................................................................x Chapter I. PRIMATES AT THE EXTREMES ..................................................1 Introduction: Primates in marginal habitats ......................................1 Prosimii .............................................................................................2 -

On Douc Langurs (Pygathrix Spp.)

Vietnamese Journal of Primatology (2010) 4, 57-68 The Pedicinus species (Insecta, Phthiraptera, Anoplura, Pedicinidae) on douc langurs (Pygathrix spp.) Eberhard Mey Museum of Natural History at the State Museum Heidecksburg, Schloßbezirk 1, D-07407 Rudolstadt, Germany. <[email protected]> Key words: Pygathrix spp., lice, Pedicinus, new species, Vietnam Summary All three species of Southeast-Asian douc langurs (Pygathrix spp.) harbor a host-specific species of Pedicinus (Neopedicinus). Using freshly collected material of known provenance, these were identified as Pedicinus tongkinensis Mey, 1994 ex Pygathrix nemaeus, Pedicinus atratulus nov. spec. ex Pygathrix nigripes, and Pedicinus curtipenitus nov. spec. ex Pygathrix cinerea. The three species described here are closely related to each other and belong to the newly created “ancoratus species group” within the subgenus Neopedicinus. Loài Pedicinus (Insecta, Phthiraptera, Anoplura, Pedicinidae) trên các loài Chà vá (Pygathrix spp.) ở Đông Nam Á Tóm tắt Cả ba loài chà vá (Pygathrix spp.) của Đông Nam Á là nơi trú ngụ của một loài ký sinh Pedicinus (Neopedicinus). Sử dụng vật liệu được thu thập tươi từ nguồn gốc đã biết, các loài này được xác định là Pedicinus tongkinensis Mey, 1994 ex Pygathrix nemaeus, Pedicinus atratulus nov. spec. ex Pygathrix nigripes, và Pedicinus curtipenitus nov. spec. ex Pygathrix cinerea. Ba loài được mô tả ở đây có quan hệ gần gũi với nhau và thuộc về “nhóm loài ancoratus” mới được tạo ra trong giống phụ Neopedicinus. Introduction The colobine genus of the douc langurs Pygathrix E. Geoffroy St.-Hilaire, 1812 is endemic to Indochina. Three monotypic species are distinguished (Roos & Nadler, 2001, Nadler et al., 2003, Nadler, 2007). -

Ontogeny of Positional Behavior in Captive Silvered Langurs (Trachypithecus Cristatus)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KnowledgeBank at OSU Ontogeny of Positional Behavior in Captive Silvered Langurs (Trachypithecus cristatus) A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for graduation with research distinction in Anthropological Science in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Amy Eakins The Ohio State University March 2010 Project Advisor: Professor W. Scott McGraw, Department of Anthropology ABSTRACT Compared to most other mammalian groups, primates are known for the great diversity of positional behavior they exhibit. Their positional repertoire is not static through time, but rather changes with age. As primates age and body size increases, the manner in which animals navigate their environment responds to shifting biomechanical, nutritional, socio-behavioral and reproductive factors. In this study, I examined positional behavior in a colony of captive colobine monkeys, hypothesizing that locomotor and postural diversity will increase with age due to changing physiological and ecological processes. I predicted that as animals mature, their positional diversity will increase as they become more adept at negotiating their three- dimensional environments. I examined age effects on positional behavior in silvered langurs (Trachypithecus cristatus) housed at the Columbus Zoo. Data were collected from January – August 2009 using instantaneous focal animal sampling on a breeding group containing four adults, two juveniles, and one infant. During each scan I recorded the focal animal’s identity, maintenance activity, substrate, and postural (19 categories) or locomotor (12 categories) behavior. Chi-square tests were performed on the data set of 4504 scans. -

Social Organization of Shortridge's Capped Langur (Trachypithecus

ZOOLOGICAL RESEARCH Social organization of Shortridge’s capped langur (Trachypithecus shortridgei) at the Dulongjiang Valley in Yunnan, China Ying-Chun LI1, †, Feng LIU1, †, Xiao-Yang HE2, Chi MA3, Jun SUN2, Dong-Hui LI2, Wen XIAO3, *, Liang-Wei CUI1,4, * 1 Forestry Faculty, Southwest Forestry University, Kunming, Yunnan 650224, China 2 Nujiang Administration Bureau, Gaoligongshan National Nature Reserve, Liuku, Yunnan 673100, China 3 Institute of Eastern-Himalaya Biodiversity Research, Dali University, Dali, Yunnan 671003, China 4 College of Life Sciences, Northwest University, Xi’an, 710069, China ABSTRACT organization can be categorized into solitary, pair-living and group-living speceis (Kappeler & van Schaik 2002). Solitary Non-human primates often live in socially stable individuals typically forage alone (Boinski & Garber, 2000) and groups characterized by bonded relationships their activities are desynchronized with each other both spatially among individuals. Social organization can be used and temporally (Charles-Dominique, 1978). Except for orangutan, to evaluate living conditions and expansion potential. most solitary primate species are nocturnal (Kappeler & van Bisexual group size, ratio of males to females and Schaik, 2002). Pair-living species refer to couples of one adult group composition are essential elements male and one adult female (Kappeler, 1999), such as gibbons. determining the type of social organization. Although Most primates live in bisexual groups (van Schaik & Kappeler, the first report on Shortridge’s capped langurs 1997), which are much more stable compared with other (Trachypithecus shortridgei) was in the 1970s, until mammals, and consist of more than two adults. Group living now, the species only inhabits forests of the primates displayed a diversity with respect to the size, sex ratio Dulongjiang valley in northwest Yunnan, China, with and temporal stabitliy of compositioin. -

The Socioecology, and the Effects of Human Activity on It, of the Annamese Silvered Langur ( Trachypithecus Margarita ) in Northeastern Cambodia

The Socioecology, and the Effects of Human Activity on It, of the Annamese Silvered Langur ( Trachypithecus margarita ) in Northeastern Cambodia Álvaro González Monge A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University School of Archaeology and Anthropology Submitted in March, 2016 Copyright by Álvaro González Monge, 2016 All Rights Reserved Statement of originality The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original and my own work, except where acknowledged. This material has not been submitted either in whole or in part, for a degree at this or other university Álvaro González Monge In memoriam: GANG HU JOAQUIM JOSEP VEÀ BARÓ Acknowledgements This project wouldn’t have successfully arrived at its conclusion without the help of an astounding amount of people. I wanted to thank many more but I think two and a half pages of this must be testing for many. I’m forever indebted to my academic supervisors, for steering me towards meaningful research and pointing out my endless flaws with endless patience, for the encouragement and heaps of valuable feedback. Whatever useful information in this thesis is largely due to them: Professor Colin Groves, for accepting me as a student which I think is one of the highest honors that can be given to a person in our field of work, and his unquenchable thirst for all mammalian bits of information I brought to his attention. Dr. Alison Behie, for her patience in greatly helping me focus on the particular topics treated in this thesis and her invaluable feedback on my research. -

Final Report of Douc Langur

Final Report Prepared by Long Thang Ha A field survey for the grey-shanked douc langurs (Pygathrix cinerea ) in Vietnam December/2004 Cuc Phuong, Vietnam A field survey on the grey-shanked douc langurs Project members Project Advisor: Tilo Nadler Project Manager Frankfurt Zoological Society Endangered Primate Rescue Centre Cuc Phuong National Park Nho Quan District Ninh Binh Province Vietnam 0084 (0) 30 848002 [email protected] Project Leader: Ha Thang Long Project Biologist Endangered Primate Rescue Centre Cuc Phuong National Park Nho Quan District Ninh Binh Province Vietnam 0084 (0) 30 848002 [email protected] [email protected] Project Member: Luu Tuong Bach Project Biologist Endangered Primate Rescue Centre Cuc Phuong National Park Nho Quan District Ninh Binh Province Vietnam 0084 (0) 30 848002 [email protected] Field Staffs: Rangers in Kon Cha Rang NR And Kon Ka Kinh NP BP Conservation Programme, 2004 2 A field survey on the grey-shanked douc langurs List of figures Fig.1: Distinguished three species of douc langurs in Indochina Fig.2: Map of surveyed area Fig.3: An interview in Kon Cha Rang natural reserve area Fig.4: A grey-shanked douc langur in Kon Cha Rang natural reserve area Fig.5: Distribution of grey-shanked douc in Kon Cha Rang, Kon Ka Kinh and buffer zone Fig.6: A grey-shanked douc langur in Kon Ka Kinh national park Fig.7: Collecting faeces sample in the field Fig.8: A skull of a douc langur collected in Ngut Mountain, Kon Ka Kinh NP Fig.9: Habitat of douc langur in Kon Cha Rang Fig.10: Habitat of douc langur in Kon Ka Kinh Fig.11: Stuffs of douc langurs in Son Lang village Fig.12: Traps were collected in the field Fig.13: Logging operation in the buffer zone area of Kon Cha Rang Fig.14: A civet was trapped in Kon Ka Kinh Fig.15: Illegal logging in Kon Ka Kinh Fig.16: Clear cutting for agriculture land Fig.17: Distribution of the grey-shanked douc langur before survey Fig.18: Distribution of the grey-shanked douc langur after survey Fig.19: Percentage of presence/absence in the surveyed transects.