(Pygathrix Cinerea) at Kon Ka Kinh National Park, Vietnam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primates of the Southern Mentawai Islands

Primate Conservation 2018 (32): 193-203 The Status of Primates in the Southern Mentawai Islands, Indonesia Ahmad Yanuar1 and Jatna Supriatna2 1Department of Biology and Post-graduate Program in Biology Conservation, Tropical Biodiversity Conservation Center- Universitas Nasional, Jl. RM. Harsono, Jakarta, Indonesia 2Department of Biology, FMIPA and Research Center for Climate Change, University of Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia Abstract: Populations of the primates native to the Mentawai Islands—Kloss’ gibbon Hylobates klossii, the Mentawai langur Presbytis potenziani, the Mentawai pig-tailed macaque Macaca pagensis, and the snub-nosed pig-tailed monkey Simias con- color—persist in disturbed and undisturbed forests and forest patches in Sipora, North Pagai and South Pagai. We used the line-transect method to survey primates in Sipora and the Pagai Islands and estimate their population densities. We walked 157.5 km and 185.6 km of line transects on Sipora and on the Pagai Islands, respectively, and obtained 93 sightings on Sipora and 109 sightings on the Pagai Islands. On Sipora, we estimated population densities for H. klossii, P. potenziani, and S. concolor in an area of 9.5 km², and M. pagensis in an area of 12.6 km². On the Pagai Islands, we estimated the population densities of the four primates in an area of 11.1 km². Simias concolor was found to have the lowest group densities on Sipora, whilst P. potenziani had the highest group densities. On the Pagai Islands, H. klossii was the least abundant and M. pagensis had the highest group densities. Primate populations, notably of the snub-nosed pig-tailed monkey and Kloss’ gibbon, are reduced and threatened on the southern Mentawai Islands. -

Title SOS : Save Our Swamps for Peat's Sake Author(S) Hon, Jason Citation

Title SOS : save our swamps for peat's sake Author(s) Hon, Jason SANSAI : An Environmental Journal for the Global Citation Community (2011), 5: 51-65 Issue Date 2011-04-12 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/143608 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University SOS: save our swamps for peatʼs sake JASON HON Abstract The Malaysian governmentʼs scheme for the agricultural intensification of oil palm production is putting increasing pressure on lowland areas dominated by peat swamp forests.This paper focuses on the peat swamp forests of Sarawak, home to 64 per cent of the peat swamp forests in Malaysia and earmarked under the Malaysian governmentʼs Third National Agriculture Policy (1998-2010) for the development and intensification of the oil palm industry.Sarawakʼs tropical peat swamp forests form a unique ecosystem, where rare plant and animal species, such as the alan tree and the red-banded langur, can be found.They also play a vital role in maintaining the carbon balance, storing up to 10 times more carbon per hectare than other tropical forests. Draining these forests for agricultural purposes endangers the unique species of flora and fauna that live in them and increases the likelihood of uncontrollable peat fires, which emit lethal smoke that can pose a huge environmental risk to the health of humans and wildlife.This paper calls for a radical reassessment of current agricultural policies by the Malaysian government and highlights the need for concerted effort to protect the fragile ecosystems of Sarawakʼs endangered -

Colobus Angolensis Palliatus) in an East African Coastal Forest

African Primates 7 (2): 203-210 (2012) Activity Budgets of Peters’ Angola Black-and-White Colobus (Colobus angolensis palliatus) in an East African Coastal Forest Zeno Wijtten1, Emma Hankinson1, Timothy Pellissier2, Matthew Nuttall1 & Richard Lemarkat3 1Global Vision International (GVI) Kenya 2University of Winnipeg, Winnipeg, Canada 3Kenyan Wildlife Services (KWS), Kenya Abstract: Activity budgets of primates are commonly associated with strategies of energy conservation and are affected by a range of variables. In order to establish a solid basis for studies of colobine monkey food preference, food availability, group size, competition and movement, and also to aid conservation efforts, we studied activity of individuals from social groups of Colobus angolensis palliatus in a coastal forest patch in southeastern Kenya. Our observations (N = 461 hours) were conducted year-round, over a period of three years. In our Colobus angolensis palliatus study population, there was a relatively low mean group size of 5.6 ± SD 2.7. Resting, feeding, moving and socializing took up 64%, 22%, 3% and 4% of their time, respectively. In the dry season, as opposed to the wet season, the colobus increased the time they spent feeding, traveling, and being alert, and decreased the time they spent resting. General activity levels and group sizes are low compared to those for other populations of Colobus spp. We suggest that Peters’ Angola black-and-white colobus often live (including at our study site) under low preferred-food availability conditions and, as a result, are adapted to lower activity levels. With East African coastal forest declining rapidly, comparative studies focusing on C. -

Gia-Lai-Electricity-Joint-Stock-Company

2018 ANNUAL REPORT ABBREVIATIONS AGM : Annual General Meeting BOD : Board Of Directors BOM : Board Of Management CAGR : Compounded Annual Growth Rate CEO : Chief Executive Officer COD : Commercial Operation Date CG : Corporate Governance CIT : Corporate Income Tax COGS : Cost Of Goods Sold EBIT : Earnings Before Interest and Taxes EBITDA : Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation And Amortization EGM : Extraordinary General Meeting EHSS : Enviroment - Health - Social Policy - Safety EPC : Engineering Procurement and Construction EVN : Viet Nam Electricity FiT : Feed In Tariff FS : Financial Statement GEC : Gia Lai Electricity Joint Stock Company HR : Human Resources JSC : Joint Stock Company LNG : Liquefied Natural Gas M&A : Mergers and Acquisitions MOIT : Ministry Of Industry and Trade NPAT : Net Profit After Taxes SG&A : Selling, General And Administration PATMI : Profit After Tax and Minority Interests PBT : Profit Before Tax PPA : Power Purchase Agreement R&D : Research and Development ROAA : Return On Average Assets ROAE : Return On Average Equity YOY : Year On Year GEC's Head Office 2 2018 ANNUAL REPORT www.geccom.vn 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS CÔNG TY CP ĐIN GIA LAI 02 ABBREVIATIONS 04 TABLE OF CONTENTS 06 REMARKABLE FIGURES 10 COMMITMENTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES 12 Vision - Mission - Core value 13 17 sustainable development goals of United Nations 18 Commitments to the truth and fairness the 2018 Annual Report 20 Interview with Chairman of the Board 24 Profile of the Board of Directors 28 Letter to Shareholders from the CEO 32 Profile -

A Note on Responses of Juvenile Javan Lutungs (Trachypithecus Auratus Mauritius) Against Attempted Predation by Crested Goshawks (Accipter Trivirgatus)

人と自然 Humans and Nature 25: 105−110 (2014) Report A note on responses of juvenile Javan lutungs (Trachypithecus auratus mauritius) against attempted predation by crested goshawks (Accipter trivirgatus) Yamato TSUJI 1*, Hiroyoshi HIGUCHI 2 and Bambang SURYOBROTO 3 1 Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University, Inuyama, Japan 2 Graduate School of Media and Governance, Keio University, Fujisawa, Japan 3 Bogor Agricultural University, Java West, Indonesia Abstract On October 31st, 2013, we unexpectedly observed attempted predation of two juvenile Javan lutungs (Trachypithecus auratus mauritius) by adult crested goshawks (Accipter trivirgatus), in Pangandaran Nature Reserve, West Java, Indonesia. The goshawks flew over a group of feeding lutungs, attempting attacks only on juvenile lutungs from the rear, while emitting tweeting calls. The attacks involved two different birds (probably a pair) in turn from different directions. The attacks by the goshawks were repeated six times during our observation period (between 13:51 and 13:58), but none of the attempts was successful. During the attacks, no other lutungs in the group showed any anti-predator behavior (such as emitting alarm calls or escaping) against the goshawks perhaps because their body weight (6-10 kg) was much larger than that of goshawk (0.4-0.6 kg). To our knowledge, this is the first detailed report of hunting-related behavior to primates by this raptor species. Key words: Accipter trivirgatus, crested goshawk, Javan lutung, Pangandaran, predation, Trachypithecus auratus mauritius Introduction primates has been conducted for over 50 years. However, with the exception of Philippine eagles Predation is considered to be a principal selective (Pithecophaga jefferyi) and hawk-eagles (Spizaetus force leading to the evolution of behavioral traits spp.), reports on the predation of primates by raptors and social systems in primates (van Schaik, 1983; in Asia are limited (Ferguson-Lee and Christie, 2001; Hart, 2007), although there are few case studies on Hart, 2007; Fam and Nijman, 2011). -

World's Most Endangered Primates

Primates in Peril The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018 Edited by Christoph Schwitzer, Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands, Federica Chiozza, Elizabeth A. Williamson, Elizabeth J. Macfie, Janette Wallis and Alison Cotton Illustrations by Stephen D. Nash IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG) International Primatological Society (IPS) Conservation International (CI) Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Published by: IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Copyright: ©2017 Conservation International All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Inquiries to the publisher should be directed to the following address: Russell A. Mittermeier, Chair, IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, VA 22202, USA. Citation (report): Schwitzer, C., Mittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B., Chiozza, F., Williamson, E.A., Macfie, E.J., Wallis, J. and Cotton, A. (eds.). 2017. Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA. 99 pp. Citation (species): Salmona, J., Patel, E.R., Chikhi, L. and Banks, M.A. 2017. Propithecus perrieri (Lavauden, 1931). In: C. Schwitzer, R.A. Mittermeier, A.B. Rylands, F. Chiozza, E.A. Williamson, E.J. Macfie, J. Wallis and A. Cotton (eds.), Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018, pp. 40-43. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA. -

Habitat Suitability of Proboscis Monkey (Nasalis Larvatus) in Berau Delta, East Kalimantan, Indonesia

BIODIVERSITAS ISSN: 1412-033X Volume 21, Number 11, November 2020 E-ISSN: 2085-4722 Pages: 5155-5163 DOI: 10.13057/biodiv/d211121 Habitat suitability of Proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus) in Berau Delta, East Kalimantan, Indonesia TRI ATMOKO1,2,♥, ANI MARDIASTUTI3♥♥, M. BISMARK4, LILIK BUDI PRASETYO3, ♥♥♥, ENTANG ISKANDAR5, ♥♥♥♥ 1Research and Development Institute for Natural Resources Conservation Technology. Jl. Soekarno-Hatta Km 38, Samboja, Samarinda 75271, East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Tel.: +62-542-7217663, Fax.: +62-542-7217665, ♥email: [email protected], [email protected]. 2Program of Primatology, Institut Pertanian Bogor. Jl. Lodaya II No. 5, Bogor 16151, West Java, Indonesia 3Department of Forest Resource Conservation and Ecotourism, Faculty of Forestry and Environment, Institut Pertanian Bogor. Jl. Lingkar Akademik, Kampus IPB Dramaga, Bogor16680, West Java, Indonesia. Tel.: +62-251-8621677, ♥♥email: [email protected], ♥♥♥[email protected] 4Forest Research and Development Center. Jl. Gunung Batu No 5, Bogor 16118, West Java, Indonesia 5Primate Research Center, Institut Pertanian Bogor. Jl. Lodaya II No. 5, Bogor 16151, West Java, Indonesia. Tel./fax.: +62-251-8320417, ♥♥♥♥email: [email protected] Manuscript received: 1 October 2020. Revision accepted: 13 October 2020. Abstract. Atmoko T, Mardiastuti A, Bismark M, Prasetyo LB, Iskandar E. 2020. Habitat suitability of Proboscis Monkey (Nasalis larvatus) in Berau Delta, East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 21: 5155-5163. Habitat suitability of Proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus) in Berau Delta, East Kalimantan, Indonesia. The proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus) is an endemic species to Borneo's island and is largely confined to mangrove, riverine, and swamp forests. Most of their habitat is outside the conservation due to degraded and habitat converted. -

Bioko Red Colobus Piliocolobus Pennantii Pennantii (Waterhouse, 1838) Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea (2004, 2006, 2010, 2012)

Bioko Red Colobus Piliocolobus pennantii pennantii (Waterhouse, 1838) Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea (2004, 2006, 2010, 2012) Drew T. Cronin, Gail W. Hearn & John F. Oates Bioko red colobus (Piliocolobus pennantii pennantii) (Illustration: Stephen D. Nash) Pennant’s red colobus monkey Piliocolobus pennantii is P. p. pennantii is threatened by bushmeat hunting, presently regarded by the IUCN Red List as comprising most notably since the early 1980s when a commercial three subspecies: P. pennantii pennantii of Bioko, P. p. bushmeat market appeared in the town of Malabo epieni of the Niger Delta, and P. p. bouvieri of the Congo (Butynski and Koster 1994). Following the discovery Republic. Some accounts give full species status to of offshore oil in 1996, and the subsequent expansion all three of these monkeys (Groves 2007; Oates 2011; of Equatorial Guinea’s economy, rising urban demand Groves and Ting 2013). P. p. pennantii is currently led to increased numbers of primate carcasses in the classified as Endangered (Oates and Struhsaker 2008). bushmeat market (Morra et al. 2009; Cronin 2013). In November 2007, a primate hunting ban was enacted Piliocolobus pennantii pennantii may once have occurred on Bioko, but it lacked any realistic enforcement and over most of Bioko, but it is now probably limited to an contributed to a spike in the numbers of monkeys in the area of less than 300 km² within the Gran Caldera and market. Between October 1997 and September 2010, a 510 km² range in the Southern Highlands Scientific a total of 1,754 P. p. pennantii were observed for sale Reserve (GCSH) (Cronin et al. -

Controlled Alien Species -Common Name

Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Amphibians by Common Name -3 species- (Updated December 2009) Frogs Common Name Family Genus Species Poison Dart Frog, Black-Legged Dendrobatidae Phyllobates bicolor Poison Dart Frog, Golden Dendrobatidae Phyllobates terribilis Poison Dart Frog, Kokoe Dendrobatidae Phyllobates aurotaenia Page 1 of 50 Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Birds by Common Name -3 species- (Updated December 2009) Birds Common Name Family Genus Species Cassowary, Dwarf Cassuariidae Casuarius bennetti Cassowary, Northern Cassuariidae Casuarius unappendiculatus Cassowary, Southern Cassuariidae Casuarius casuarius Page 2 of 50 Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Mammals by Common Name -437 species- (Updated March 2010) Common Name Family Genus Species Artiodactyla (Even-toed Ungulates) Bovines Buffalo, African Bovidae Syncerus caffer Gaur Bovidae Bos frontalis Girrafe Giraffe Giraffidae Giraffa camelopardalis Hippopotami Hippopotamus Hippopotamidae Hippopotamus amphibious Hippopotamus, Madagascan Pygmy Hippopotamidae Hexaprotodon liberiensis Carnivora Canidae (Dog-like) Coyote, Jackals & Wolves Coyote (not native to BC) Canidae Canis latrans Dingo Canidae Canis lupus Jackal, Black-Backed Canidae Canis mesomelas Jackal, Golden Canidae Canis aureus Jackal Side-Striped Canidae Canis adustus Wolf, Gray (not native to BC) Canidae Canis lupus Wolf, Maned Canidae Chrysocyon rachyurus Wolf, Red Canidae Canis rufus Wolf, Ethiopian -

Ontogeny of Positional Behavior in Captive Silvered Langurs (Trachypithecus Cristatus)

Ontogeny of Positional Behavior in Captive Silvered Langurs (Trachypithecus cristatus) A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for graduation with research distinction in Anthropological Science in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Amy Eakins The Ohio State University March 2010 Project Advisor: Professor W. Scott McGraw, Department of Anthropology ABSTRACT Compared to most other mammalian groups, primates are known for the great diversity of positional behavior they exhibit. Their positional repertoire is not static through time, but rather changes with age. As primates age and body size increases, the manner in which animals navigate their environment responds to shifting biomechanical, nutritional, socio-behavioral and reproductive factors. In this study, I examined positional behavior in a colony of captive colobine monkeys, hypothesizing that locomotor and postural diversity will increase with age due to changing physiological and ecological processes. I predicted that as animals mature, their positional diversity will increase as they become more adept at negotiating their three- dimensional environments. I examined age effects on positional behavior in silvered langurs (Trachypithecus cristatus) housed at the Columbus Zoo. Data were collected from January – August 2009 using instantaneous focal animal sampling on a breeding group containing four adults, two juveniles, and one infant. During each scan I recorded the focal animal’s identity, maintenance activity, substrate, and postural (19 categories) or locomotor (12 categories) behavior. Chi-square tests were performed on the data set of 4504 scans. Contrary to expectations, my analyses show that the number of observed positional behaviors did not change significantly with age, although the types of behaviors observed did change. -

A Model of Colobus and Piliocolobus Behavioural Ecology: One Folivore

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Bournemouth University Research Online Korstjens & Dunbar Colobine model 1 2 Time constraints limit group sizes and distribution in red and black-and- 3 white colobus monkeys 4 5 6 Amanda H. Korstjens 7 R.I.M. Dunbar 8 9 10 British Academy Centenary Research Project 11 School of Biological Sciences 12 University of Liverpool 13 Crown St 14 Liverpool L69 7ZB 15 England 16 17 18 Email: [email protected] 19 20 21 22 23 Short title: Colobine model 24 Korstjens & Dunbar Colobine model 25 ABSTRACT 26 Several studies have shown that, in frugivorous primates, a major constraint on group size is 27 within-group feeding competition. This relationship is less obvious in folivorous primates. 28 We investigated whether colobine group sizes are constrained by time limitations as a result 29 of their low energy diet and ruminant-like digestive system. We used climate as an easy to 30 obtain proxy for the productivity of a habitat. Using the relationships between climate, group 31 size and time budget components observed for Colobus and Piliocolobus populations at 32 different research sites, we created two taxon-specific models. In both genera, feeding time 33 increased with group size (or biomass). The models for Colobus and Piliocolobus correctly 34 predicted the presence or absence of the genus at, respectively, 86% of 148 and 84% of 156 35 African primate sites. Median predicted group sizes where the respective genera were present 36 were 19 for Colobus and 53 for Piliocolobus. -

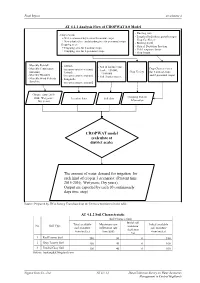

CROPWAT Model (Calculate at District Scale) the Amount of Water Demand

Final Report Attachment 4 AT 4.1.1 Analysis Flow of CROPWAT 8.0 Model - Planting date -Crop season: - Length of individual growth stages + Wet season and dry season for annual crops - Crop Coefficient + New planted tree and standing tree for perennial crops - Rooting depth - Cropping area: - Critical Depletion Fraction + Cropping area for 8 annual crops - Yield response factor + Cropping area for 6 perennial crops - Crop height - Monthly Rainfall - Altitude - Soil & landuse map - Monthly Temperature Crop Characteristics (in representative station) (scale: 1/50.000; (max,min ) Crop Variety (for 8 annual crops - Latitude 1/100.000) - Monthly Humidity and 6 perennial crops) (in representative station) - Soil characteristics. - Monthly Wind Velocity - Longitude - Sunshine (in representative station) Climate data ( 2015- Cropping Pattern 2016; Wet years; Location data Soil data Dry years) Information CROPWAT model (calculate at district scale) The amount of water demand for irrigation for each kind of crop in 3 scenarios: (Present time 2015-2016; Wet years; Dry years). Output are exported by each 10 continuously days time step) Source: Prepared by JICA Survey Team based on the Decrees mentioned in the table. AT 4.1.2 Soil Characteristic Soil Characteristic Initial soil Total available Maximum rain Initial available No Soil Type moisture soil moisture infiltration rate soil moisture depletion (mm/meter) (mm/day) (mm/meter) (%) 1 Red Loamy Soil 180 30 0 180 2 Gray Loamy Soil 160 40 0 160 3 Eroded Gray Soil 100 40 0 100 Source: baotangdat.blogspot.com Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. AT 4.1.1-1 Data Collection Survey on Water Resources Management in Central Highlands Final Report Attachment 4 AT 4.1.3 Soil Type Distribution per District Scale No.