Research Articles NAT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deforestation of Primate Habitat on Sumatra and Adjacent Islands, Indonesia

Primate Conservation 2017 (31): 71-82 Deforestation of Primate Habitat on Sumatra and Adjacent Islands, Indonesia Jatna Supriatna1,2, Asri A. Dwiyahreni2, Nurul Winarni2, Sri Mariati3,4 and Chris Margules2,5 ¹Department of Biology, FMIPA Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia 2Research Center for Climate Change, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia 3Postgraduate Program, Trisakti Institute for Tourism, Pesanggrahan, Jakarta, Indonesia 4Conservation International, Indonesia 5Centre for Tropical Environmental and Sustainability Science, College of Marine and Environmental Sciences, James Cook University, Cairns, Australia Abstract: The severe declines in forest cover on Sumatra and adjacent islands have been well-documented but that has not slowed the rate of forest loss. Here we present recent data on deforestation rates and primate distribution patterns to argue, yet again, for action to avert potential extinctions of Sumatran primates in the near future. Maps of forest loss were constructed using GIS and satellite imagery. Maps of primate distributions were estimated from published studies, museum records and expert opinion, and the two were overlaid on one another. The extent of deforestation in the provinces of Sumatra between 2000 and 2012 varied from 3.74% (11,599.9 ha in Lampung) to 49.85% (1,844,804.3 ha in Riau), with the highest rates occurring in the provinces of Riau, Jambi, Bangka Belitung and South Sumatra. During that time six species lost 50% or more of their forest habitat: the Banded langur Presbytis femoralis lost 82%, the Black-and-white langur Presbytis bicolor lost 78%, the Black-crested Sumatran langur Presbytis melalophos and the Bangka slow loris Nycticebus bancanus both lost 62%, the Lar gibbon Hylobates lar lost 54%, and the Pale-thighed langur Presbytis siamensis lost 50%. -

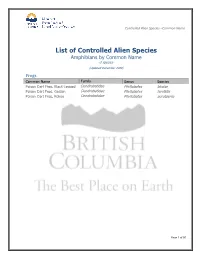

Controlled Alien Species -Common Name

Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Amphibians by Common Name -3 species- (Updated December 2009) Frogs Common Name Family Genus Species Poison Dart Frog, Black-Legged Dendrobatidae Phyllobates bicolor Poison Dart Frog, Golden Dendrobatidae Phyllobates terribilis Poison Dart Frog, Kokoe Dendrobatidae Phyllobates aurotaenia Page 1 of 50 Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Birds by Common Name -3 species- (Updated December 2009) Birds Common Name Family Genus Species Cassowary, Dwarf Cassuariidae Casuarius bennetti Cassowary, Northern Cassuariidae Casuarius unappendiculatus Cassowary, Southern Cassuariidae Casuarius casuarius Page 2 of 50 Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Mammals by Common Name -437 species- (Updated March 2010) Common Name Family Genus Species Artiodactyla (Even-toed Ungulates) Bovines Buffalo, African Bovidae Syncerus caffer Gaur Bovidae Bos frontalis Girrafe Giraffe Giraffidae Giraffa camelopardalis Hippopotami Hippopotamus Hippopotamidae Hippopotamus amphibious Hippopotamus, Madagascan Pygmy Hippopotamidae Hexaprotodon liberiensis Carnivora Canidae (Dog-like) Coyote, Jackals & Wolves Coyote (not native to BC) Canidae Canis latrans Dingo Canidae Canis lupus Jackal, Black-Backed Canidae Canis mesomelas Jackal, Golden Canidae Canis aureus Jackal Side-Striped Canidae Canis adustus Wolf, Gray (not native to BC) Canidae Canis lupus Wolf, Maned Canidae Chrysocyon rachyurus Wolf, Red Canidae Canis rufus Wolf, Ethiopian -

LEAF MONKEY, Trachypithecus Auratus Sondaicus, in the PANGANDARAN NATURE RESERVE, WEST JAVA, INDONESIA

BEHAVIOURAL ECOLOGY OF THE SILVER LEAF MONKEY, Trachypithecus auratus sondaicus, IN THE PANGANDARAN NATURE RESERVE, WEST JAVA, INDONESIA by KAREN MARGARETHA KOOL A dissertation submitted to the University of New South Wales for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Science University of New South Wales Sydney, New South Wales Australia March, 1989 SR PT02 Form 2 RETENTION THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES DECLARATION RELATING TO DISPOSITION OF PROJECT REPORT/THESIS This is to certify that I . .1�9.-.C:eo...... MQ;.r.tQ.J:£'\hP..-. .. .J�l.... being a candidate for the degree of 1)!=>.d:o.r.--.of.-.Y.hSos.Of.hy .. am fully aware of the policy of the University relating to the retention and use of higherdegree project reports and theses, namely that the University retains the copies submitted for examination and is free to allow them to be consulted or borrowed. Subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act, 1968, the University may issue a project report or thesis in whole or in part, in photostat or microfilm or other copying medium. In the light of these provisions I declare that I wish to retain my full privileges of copyright and request that neither the whole nor any portion of my project report/thesis be published by the University Librarian and that the Librarian may not authorise the publication of the whole or any part of it, and that I further declare that thispreservation of my copyright privileges shall lapse from the ... :fit.�t ............ day of ...3.o.n ....... 9..r: { ............... 19.�.<:\................. -

The World's 25 Most Endangered Primates, 2006-2008

Primate Conservation 2007 (22): 1 – 40 Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates, 2006 – 2008 Russell A. Mittermeier 1, Jonah Ratsimbazafy 2, Anthony B. Rylands 3, Liz Williamson 4, John F. Oates 5, David Mbora 6, Jörg U. Ganzhorn 7, Ernesto Rodríguez-Luna 8, Erwin Palacios 9, Eckhard W. Heymann 10, M. Cecília M. Kierulff 11, Long Yongcheng 12, Jatna Supriatna 13, Christian Roos 14, Sally Walker 15, and John M. Aguiar 3 1Conservation International, Arlington, VA, USA 2Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust – Madagascar Programme, Antananarivo, Madagascar 3Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation International, Arlington, VA, USA 4Department of Psychology, University of Stirling, Stirling, Scotland, UK 5Department of Anthropology, Hunter College, City University of New York (CUNY), New York, USA 6Department of Biological Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA 7Institute of Zoology, Ecology and Conservation, Hamburg, Germany 8Instituto de Neuroetología, Universidad Veracruzana, Veracruz, México 9Conservation International Colombia, Bogotá, DC, Colombia 10Abteilung Verhaltensforschung & Ökologie, Deutsches Primatenzentrum, Göttingen, Germany 11Fundação Parque Zoológico de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil 12The Nature Conservancy, China Program, Kunming, Yunnan, China 13Conservation International Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia 14 Gene Bank of Primates, Deutsches Primatenzentrum, Göttingen, Germany 15Zoo Outreach Organisation, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India Introduction among primatologists working in the field who had first-hand knowledge of the causes of threats to primates, both in gen- Here we report on the fourth iteration of the biennial eral and in particular with the species or communities they listing of a consensus of 25 primate species considered to study. The meeting and the review of the list of the World’s be amongst the most endangered worldwide and the most in 25 Most Endangered Primates resulted in its official endorse- need of urgent conservation measures. -

Biological Richness of Gunung Slamet, Central Java, and the Need for Its Protection

Biological richness of Gunung Slamet, Central Java, and the need for its protection C HRISTIAN D EVENISH,ACHMAD R IDHA J UNAID,ANDRIANSYAH,RIA S ARYANTHI S. (BAS) VAN B ALEN,FAJAR K APRAWI,GANJAR C AHYO A PRIANTO R ICHARD C. STANLEY,OLIVER P OOLE,ANDREW O WEN N. J. COLLAR and S TUART J. MARSDEN Abstract Designating protected areas remains a core strategy we discuss different options for improving the protection in biodiversity conservation. Despite high endemism, mon- status of Gunung Slamet, including designation as a tane forests across the island of Java are under-represented National Park or Essential Ecosystem. in Indonesia’s protected area network. Here, we document Keywords Conservation planning, Garrulax rufifrons the montane biodiversity of Gunung Slamet, an isolated slamatensis, Gunung Slamet, Hylobates moloch, Indonesia, volcano in Central Java, and provide evidence to support Java, species distribution models, threatened species its increased protection. During September–December , we surveyed multiple sites for birds, primates, terrestrial Supplementary material for this article is available at mammals, reptiles, amphibians and vegetation. Survey doi.org/./S methods included transects, camera traps and targeted searches at six sites, at altitudes of –, m. We used species distribution models for birds and mammals of con- servation concern to identify priority areas for protection. Introduction We recorded bird species ( globally threatened), n the face of the current global extinction crisis mammals (five globally threatened) and reptiles and I(Bradshaw et al., ; Ceballos et al., ), it is vital amphibians (two endemic). Our species distribution models to establish protected areas that can serve as biological reser- showed considerable cross-taxon congruence between im- voirs for species and ecological processes (Chape et al., ; ’ portant areas on Slamet s upper slopes, generally above Jenkins & Joppa, ; Le Saout et al., ; Venter et al., , m. -

Primate Research and Conservation in Malaysia

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by The University of North Carolina at Greensboro Archived version from NCDOCKS Institutional Repository http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/asu/ Primate Research And Conservation In Malaysia By: Susan Lappan and Nadine Ruppert Abstract Malaysia is inhabited by ≥25 nonhuman primate species from five families, one of the most diverse primate faunas on earth. Unfortunately, most Malaysian primates are threatened with extinction due to habitat loss, degradation, and fragmentation, hunting and the synergies among these processes. Here, we review research on primates and issues related to their conservation in Malaysia. Despite the charisma and cultural importance of primates, the importance of primates in ecological processes such as seed dispersal, and the robust development of biodiversity- related sciences in Malaysia, relatively little research specifically focused on wild primates has been conducted in Malaysia since the 1980s. Forest clearing for plantation agriculture has been a primary driver of forest loss and fragmentation in Malaysia. Selective logging also has primarily negative impacts on primates, but these impacts vary across primate taxa, and previously-logged forests are important habitats for many Malaysian primates. Malaysia is crossed by a dense road network, which fragments primate habitats, facilitates further human encroachment into forested areas and causes substantial mortality due to road kills. Primates in Malaysia are hunted for food or as pests, trapped for translocation due to wildlife-human conflict and hunted and trapped for illegal trade as pets. Further research on the distribution, abundance, ecology and behavioural biology of Malaysian primates is needed to inform effective management plans. -

1 Classification of Nonhuman Primates

BLBS036-Voevodin April 8, 2009 13:57 Part I: Introduction to Primatology and Virology COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL BLBS036-Voevodin April 8, 2009 13:57 BLBS036-Voevodin April 8, 2009 13:57 1 Classification of Nonhuman Primates 1.1 Introduction that the animals colloquially known as monkeys and 1.2 Classification and nomenclature of primates apes are primates. From the zoological standpoint, hu- 1.2.1 Higher primate taxa (suborder, infraorder, mans are also apes, although the use of this term is parvorder, superfamily) usually restricted to chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, 1.2.2 Molecular taxonomy and molecular and gibbons. identification of nonhuman primates 1.3 Old World monkeys 1.2. CLASSIFICATION AND NOMENCLATURE 1.3.1 Guenons and allies OF PRIMATES 1.3.1.1 African green monkeys The classification of primates, as with any zoological 1.3.1.2 Other guenons classification, is a hierarchical system of taxa (singu- 1.3.2 Baboons and allies lar form—taxon). The primate taxa are ranked in the 1.3.2.1 Baboons and geladas following descending order: 1.3.2.2 Mandrills and drills 1.3.2.3 Mangabeys Order 1.3.3 Macaques Suborder 1.3.4 Colobines Infraorder 1.4 Apes Parvorder 1.4.1 Lesser apes (gibbons and siamangs) Superfamily 1.4.2 Great apes (chimpanzees, gorillas, and Family orangutans) Subfamily 1.5 New World monkeys Tribe 1.5.1 Marmosets and tamarins Genus 1.5.2 Capuchins, owl, and squirrel monkeys Species 1.5.3 Howlers, muriquis, spider, and woolly Subspecies monkeys Species is the “elementary unit” of biodiversity. -

Taxonomy and Phylogeny of Leaf Monkeys with Focus on the Genus

ZENTRUM FÜR BIODIVERSITÄT UND NACHHALTIGE LANDNUTZUNG SEKTION BIODIVERSITÄT, ÖKOLOGIE UND NATURSCHUTZ TAXONOMY AND PHYLOGENY OF LEAF MONKEYS (COLOBINAE) WITH FOCUS ON THE GENUS PRESBYTIS (ESCHSCHOLTZ, 1821) Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Dr. rer. nat. der Mathematisch‐Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultäten der Georg‐August‐Universität zu Göttingen vorgelegt von Dipl.‐Biol. Dirk Meyer aus Berlin Göttingen, August 2011 Referent: Prof. Dr. J. Keith Hodges Koreferent: Prof. Dr. Julia Fischer vorgelegt von: Dipl.‐Biol. Dirk Meyer Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: Summary II Summary Leaf monkeys (Colobinea) constitute a very diverse group of primates with major ra‐ diations in Africa and Asia. The Asian colobines are tradionally divided into the odd‐ nosed group (Simias, Nasalis, Pygathrix, Rhinopithecus) and the langur group (Semno‐ pithecus, Trachypithecus, Presbytis). Among the langur group Presbytis constitutes a particular diverse taxon, but the phylogenetic position of Presbytis among the Asian colobines, as well as the number of Presbytis taxa and their phylogenetic relationships remain controversial. Previous molecular studies on leaf monkeys on the generic level based on incomplete sampling and revealed discordant gene trees for the Asian group. In particular the phy‐ logenetic position of Presbytis was unclear. In a comperative genetic approach, we combined presence/absence analysis of mobile elements with autosomal, X chromo‐ somal, Y chromosomal and mitochondrial sequence data from all recognized colobine genera. Our results could not clarify the phylogenetic position of Presbytis, but indi‐ cated an unidirectional gene flow from Semnopithecus into Trachypithecus via male introgression, rather than a previously proposed hybridization between Presbytis and Trachypithecus. Regarding the genus Presbytis, almost all current classifications predominantly based on morphological traits, while the only molecular study relied heavily on captive ani‐ mals of uncertain origin. -

The Ecology and Conservation of Presbytis Rubicunda

The ecology and conservation of Presbytis rubicunda DAVID ALAN EHLERS SMITH This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy on the Basis of Published Work Oxford Brookes University March 2015 1 David A. Ehlers Smith Sabangau Red Langur Research Project The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project [email protected] – www.outrop.com 2 For Yvie, Supian, Francis and Ann Juvenile male Presbytis rubicunda 3 Abstract From 2009 to 2014 I conducted research that contributes toward a synthesis of techniques to best inform conservation management schemes for the protection of the endemic Presbytis monkeys on the Southeast Asian island of Borneo, using the red langur (Presbytis rubicunda) as a case study. To achieve this, I conducted ecological niche modelling of distributional patterns for Presbytis species; assessed land-use policies affecting their persistence likelihood, and reviewed the location and efficacy of the Protected Area Network (PAN) throughout distributions; conducted population density surveys within an under-studied habitat (tropical peat- swamp forests) and a small but highly productive mast-fruiting habitat, and founded a monitoring programme of Presbytis rubicunda concerned with establishing the ecological parameters (including behavioural, feeding and ranging ecology) required to advise conservation programmes. The ecological niche modelling of Presbytis distributions demonstrated that the PAN does not provide effective protection, and land- use policies throughout distributions may continue causing population declines. Data from 27 months of fieldwork provided convincing evidence that the non-mast fruiting characteristics of tropical peat-swamp forests on Borneo had a profound effect on the ecology of Presbytis rubicunda. -

Terrestrial Mammal Community Richness and Temporal Overlap Between Tigers and Other Carnivores in Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park, Sumatra

Animal Biodiversity and Conservation 43.1 (2020) 97 Terrestrial mammal community richness and temporal overlap between tigers and other carnivores in Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park, Sumatra M. L. Allen, M. C. Sibarani, L. Utoyo, M. Krofel Allen, M. L., Sibarani, M. C., Utoyo, L., Krofel, M., 2020. Terrestrial mammal community richness and temporal overlap between tigers and other carnivores in Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park, Sumatra. Animal Biodi- versity and Conservation, 43.1: 97–107, DOI: https://doi.org/10.32800/abc.2020.43.0097 Abstract Terrestrial mammal community richness and temporal overlap between tigers and other carnivores in Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park, Sumatra. Rapid and widespread biodiversity losses around the world make it important to survey and monitor endangered species, especially in biodiversity hotspots. Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park (BBSNP) is one of the largest conserved areas on the island of Sumatra, and is important for the conservation of many threatened species. Sumatran tigers (Panthera tigris sumatrae) are critically endangered and serve as an umbrella species for conservation, but may also affect the activity and distribution of other carnivores. We deployed camera traps for 8 years in an area of Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park (BBSNP) with little human activity to document the local terrestrial mammal community and investigate tiger spatial and temporal overlap with other carnivore species. We detected 39 mammal species including Sumatran tiger and several other threatened mammals. Annual species richness averaged 21.5 (range 19–24) mammals, and re- mained stable over time. The mammal order significantly affected annual detection of species and the number of cameras where a species was detected, while species conservation status did not. -

Indonesian Primate Profile Presbytis Comata Common Names: English: the Javan Surili, Grizzled Leaf Monkey; Indonesia: Surili, Rekrekan

Jurnal Primatologi Indonesia, Vol. 16, No. 1, Januari 2019, hlm. 1-2 ISSN 1410-5373 Indonesian Primate Profile Presbytis comata Common Names: English: the javan surili, grizzled leaf monkey; Indonesia: surili, rekrekan Figure 1 The javan surili (Presbytis comata) (source: Iskandar 2005) The javan surili (Presbytis comata), is estimated that fewer than 1,000 exist today in one of the endemic Javanese primates whose their natural habitat and only 4% of their natural distribution is limited to rain forests in the west habitat remains. Most of the loss of its original to the middle of Java Island (Nijman 1997). habitat is due to the clearing of the rainforests People on the slopes of Mount Merbabu know in Indonesia. Only 4% of its original habitat this primate as a rekrekan, as in other areas in remains and the population has decreased by Central Java. Until now, there are differences at least 50% in the last ten years (Nijman dan of opinion regarding the taxonomy of this Richardson 2008). endemic primate. Nijman (1997) considers that all types of surili on Java Island are one species of P. comata. Meanwhile, Brandon-Jones et al. References (2004) separated surili species in the central part of Java as their own species, P. fredericae. Roos Bennett A, Davies G. 1994. The Ecology of et al. (2014) state that there are two subspecies Asian Colobinaes. Di dalam Davies AG, of Lutung Surili namely P. c. comata in western Oates JF, editor. Colobine Monkeys: Java and P. c. fredericae in central Java. Their Ecology, Behaviour, and Evolution. The existence of Lutung Surili in Cambridge University Pr hlm. -

Presbytis Comata) Population Density in a Production Forest in Kuningan District, West Java, Indonesia

Primate Conservation 2020 (34): 153-165 Controlling Factors of Grizzled Leaf Monkey (Presbytis comata) Population Density in a Production Forest in Kuningan District, West Java, Indonesia Toto Supartono1, Lilik Budi Prasetyo2, Agus Hikmat2 and Agus Priyono Kartono2 ¹Department of Forestry, Faculty of Forestry, Kuningan University, Cijoho, Kuningan District, Indonesia ²Department of Forest Resources Conservation and Ecotourism, Faculty of Forestry, IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia Abstract: Land use change and deforestation continues in Indonesia at an alarming rate, resulting in widespread loss of habitat for wildlife. In this study, we propose that a production forest can serve as a refuge for otherwise afflicted animal populations. Information on population densities and an understanding of the influencing factors are important to evaluate the efficacy of pro- tected areas and production forest. Very little is known in this regard, however, for the species in question here, the Endangered grizzled leaf monkey, Presbytis comata. Here we report on a study to estimate the population density of this langur (and other primates) in a production forest and to identify the controlling factors. We conducted population surveys in 19 forest patches and recorded the numbers and density of tree species that figure in the diet of the langur. We also counted tree stumps, an indication of the intensity of logging. We measured the distance of each of the 19 forest patches to the nearest road, the nearest settlement, and to other forest patches. Descriptive statistics and multiple linear regression were used in data analysis. We recorded popula- tion densities of 36.97 to 54.12 individuals/km² (mean = 44.71 ind./km²).