Surviving Through the Post-Cold War Era: the Evolution of Foreign Policy in North Korea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOUTH KOREA BETWEEN EAGLE and DRAGON Perceptual Ambivalence and Strategic Dilemma

SOUTH KOREA BETWEEN EAGLE AND DRAGON Perceptual Ambivalence and Strategic Dilemma Jae Ho Chung The decade of the 1990s began with the demise of the Soviet empire and the subsequent retreat of Russia from the center stage of Northeast Asia, leaving the United States in a search to adjust its policies in the region. The “rise of China,” escalating cross-strait tension since 1995, North Korea’s nuclear brinkmanship and missile challenges, latent irreden- tism, and the pivotal economic importance of Northeast Asia have all led the United States to re-emphasize its role and involvement in the region.1 This redefinition of the American mission has in turn led to the consolidation of the U.S.-Japan alliance, exemplified by the 1997 Defense Guideline revision, as well as to the establishment of trilateral consultative organizations such as the Trilateral Coordination and Oversight Group (TCOG) among the U.S., Japan, and South Korea. The increasingly proactive posture by the U.S. has, however, generated grave strategic concerns on the part of China and Russia, which have sought to circumscribe America’s hegemonic parameters in Asia both bilaterally and multilaterally (i.e., the formation of the “Shanghai Six” and the Boao Asia Forum, as well as China’s call for an Association of Southeast Asian Nations Jae Ho Chung is Associate Professor of International Relations, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea. The author wishes to thank Bruce J. Dickson and Wu Xinbo for their helpful comments on an earlier version. Asian Survey, 41:5, pp. 777–796. ISSN: 0004–4687 Ó 2001 by The Regents of the University of California. -

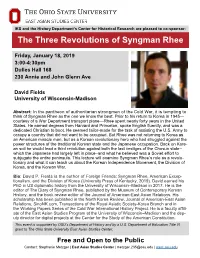

The Three Revolutions of Syngman Rhee

IKS and the History Department’s Center for Historical Research are pleased to co-sponsor: The Three Revolutions of Syngman Rhee Friday, January 18, 2019 3:00-4:30pm Dulles Hall 168 230 Annie and John Glenn Ave David Fields University of Wisconsin-Madison Abstract: In the pantheon of authoritarian strongmen of the Cold War, it is tempting to think of Syngman Rhee as the one we know the best. Prior to his return to Korea in 1945— courtesy of a War Department transport plane—Rhee spent nearly forty years in the United States. He earned degrees from Harvard and Princeton, spoke English fluently, and was a dedicated Christian to boot. He seemed tailor-made for the task of assisting the U.S. Army to occupy a country that did not want to be occupied. But Rhee was not returning to Korea as an American miracle man, but as a Korean revolutionary hero who had struggled against the power structures of the traditional Korean state and the Japanese occupation. Back on Kore- an soil he would lead a third revolution against both the last vestiges of the Chosun state– which the Japanese had largely left in place–and what he believed was a Soviet effort to subjugate the entire peninsula. This lecture will examine Syngman Rhee’s role as a revolu- tionary and what it can teach us about the Korean Independence Movement, the Division of Korea, and the Korean War. Bio: David P. Fields is the author of Foreign Friends: Syngman Rhee, American Excep- tionalism, and the Division of Korea (University Press of Kentucky, 2019). -

Democratic Republic of Congo Constitution

THE CONSTITUTION OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO, 2005 [1] Table of Contents PREAMBLE TITLE I GENERAL PROVISIONS Chapter 1 The State and Sovereignty Chapter 2 Nationality TITLE II HUMAN RIGHTS, FUNDAMENTAL LIBERTIES AND THE DUTIES OF THE CITIZEN AND THE STATE Chapter 1 Civil and Political Rights Chapter 2 Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Chapter 3 Collective Rights Chapter 4 The Duties of the Citizen TITLE III THE ORGANIZATION AND THE EXERCISE OF POWER Chapter 1 The Institutions of the Republic TITLE IV THE PROVINCES Chapter 1 The Provincial Institutions Chapter 2 The Distribution of Competences Between the Central Authority and the Provinces Chapter 3 Customary Authority TITLE V THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL TITLE VI DEMOCRACY-SUPPORTING INSTITUTIONS Chapter 1 The Independent National Electoral Commission Chapter 2 The High Council for Audiovisual Media and Communication TITLE VII INTERNATIONAL TREATIES AND AGREEMENTS TITLE VIII THE REVISION OF THE CONSTITUTION TITLE IX TRANSITORY AND FINAL PROVISIONS PREAMBLE We, the Congolese People, United by destiny and history around the noble ideas of liberty, fraternity, solidarity, justice, peace and work; Driven by our common will to build in the heart of Africa a State under the rule of law and a powerful and prosperous Nation based on a real political, economic, social and cultural democracy; Considering that injustice and its corollaries, impunity, nepotism, regionalism, tribalism, clan rule and patronage are, due to their manifold vices, at the origin of the general decline -

Landscapes of Korean and Korean American Biblical Interpretation

BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION AMERICAN AND KOREAN LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN International Voices in Biblical Studies In this first of its kind collection of Korean and Korean American Landscapes of Korean biblical interpretation, essays by established and emerging scholars reflect a range of historical, textual, feminist, sociological, theological, and postcolonial readings. Contributors draw upon ancient contexts and Korean American and even recent events in South Korea to shed light on familiar passages such as King Manasseh read through the Sewol Ferry Tragedy, David and Bathsheba’s narrative as the backdrop to the prohibition against Biblical Interpretation adultery, rereading the virtuous women in Proverbs 31:10–31 through a Korean woman’s experience, visualizing the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and demarcations in Galatians, and introducing the extrabiblical story of Eve and Norea, her daughter, through story (re)telling. This volume of essays introduces Korean and Korean American biblical interpretation to scholars and students interested in both traditional and contemporary contextual interpretations. Exile as Forced Migration JOHN AHN is AssociateThe Prophets Professor Speak of Hebrew on Forced Bible Migration at Howard University ThusSchool Says of Divinity.the LORD: He Essays is the on author the Former of and Latter Prophets in (2010) Honor ofand Robert coeditor R. Wilson of (2015) and (2009). Ahn Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-379-6) available at http://ivbs.sbl-site.org/home.aspx Edited by John Ahn LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION INTERNATIONAL VOICES IN BIBLICAL STUDIES Jione Havea Jin Young Choi Musa W. Dube David Joy Nasili Vaka’uta Gerald O. West Number 10 LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION Edited by John Ahn Atlanta Copyright © 2019 by SBL Press All rights reserved. -

The Sunshine Policy and Its Aftermath

The Sunshine Policy and its Aftermath Youngho Kim (Department of Political Science, Sungshin Women's University) I. Introduction The Kim Dae-jung administration's sunshine policy represents a paradigm shift in South Korea's policy toward North Korea. The traditional paradigm was the containment of North Korea based on the defense alliance between the United States and the Republic of Korea. During his presidency the containment policy was replaced by the proactive engagement policy to induce gradual changes of the North Korean regime through reconciliation and economic cooperation. His presidency experienced the North Korea's naval provocations in 1999 and 2002. The emergence of the Bush administration with reservations on the sunshine policy and suspicion of the Agreed Framework created strains on US-ROK alliance. Yet the sunshine policy was pursued without interruption until the end of his presidency. The dispatch of the special envoy to find a peaceful solution for the North Korea's nuclear standoff in January 2003 represents last-minute efforts to rescue the engagement policy. The next administration cannot be free from the legacies of the sunshine policy. Indeed, President-elect Roh Moo-hyun is expected to carry on the former administration's engagement policy toward North Korea.1 Critical assessments of the theoretical backgrounds and the achievements of the sunshine policy will help the Roh Moo-hyun administration to devise and implement its new policies toward North Korea. The Kim Dae-jung administration also raises theoretical questions in pursuit of the sunshine policy. One of the most important issues is the announcement of the policy to dissolve the Cold War structure on the Korean peninsula the administration considers one of the barriers to improving inter-Korean relations. -

The Role of Education in Taming Authoritarian Attitudes

The Role of Education in Taming Authoritarian Attitudes WITH A FOREWORD BY JOHN J. DEGIOIA, PRESIDENT GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY Anthony P. Carnevale Nicole Smith Lenka Dražanová Artem Gulish Kathryn Peltier Campbell 2020 Center on Education and the Workforce McCourt School of Public Policy Reprint permissions [TK] Reprint Permission The Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce carries a Creative Commons license, which permits noncommercial reuse of any of our content when proper attribution is provided. You are free to copy, display, and distribute our work, or include our content in derivative works, under the following conditions: Attribution: You must clearly attribute the work to the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce and provide a print or digital copy of the work to [email protected]. Our preference is to cite figures and tables as follows: Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, The Role of Education in Taming Authoritarian Attitudes, 2020. Noncommercial Use: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Written permission must be obtained from the owners of the copy/literary rights and from Georgetown University for any publication or commercial use of reproductions. Approval: If you are using one or more of our available data representations (figures, charts, tables, etc.), please visit our website at cew.georgetown.edu/publications/reprint- permission for more information. For the full legal code of this Creative Commons license, please visit creativecommons.org. Email [email protected] with any questions. 2 THE ROLE OF EDUCATION IN TAMING AUTHORITARIAN ATTITUDES The Role of Education in Taming Authoritarian Attitudes WITH A FOREWORD BY JOHN J. -

Christmas in North Korea

Christmas in North Korea Christmas in North Korea By Adnan I. Qureshi With contributions from Talha Jilani Asad Alamgir Guven Uzun Suleman Khan Christmas in North Korea By Adnan I. Qureshi This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Adnan I. Qureshi All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5054-0 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5054-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contributors .............................................................................................. x Preface ...................................................................................................... xi 1. The Journey to North Korea ............................................................... 1 1.1. Introduction to the Korean Peninsula 1.2. Tour to North Korea 1.3. Introduction to The Pyongyang Times 1.4. Arrival at Pyongyang International Airport 2. Brief History ........................................................................................ 32 2.1. The ‘Three Kingdom’ and ‘Later Three Kingdom’ periods 2.2. Goryeo kingdom 2.3. Joseon kingdom 2.4. Japanese occupation 2.5. Complete Japanese control 2.6. Post-Japanese occupation 2.7. The Korean War 3. Contemporary North Korea .............................................................. 58 3.1. The first communist dynasty and its challenges 3.2. The changing face of the communist economic structure 3.3. Nuclear power 3.4. Rocket technology 3.5. Life amidst sanctions 3.6. Mineral resources 3.7. Mutual defense treaties 3.8. Governmental structure of North Korea 3.9. -

Explaining Irredentism: the Case of Hungary and Its Transborder Minorities in Romania and Slovakia

Explaining irredentism: the case of Hungary and its transborder minorities in Romania and Slovakia by Julianna Christa Elisabeth Fuzesi A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Government London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2006 1 UMI Number: U615886 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615886 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is entirely my own. Signature Date ....... 2 UNIVERSITY OF LONDON Abstract of Thesis Author (full names) ..Julianna Christa Elisabeth Fiizesi...................................................................... Title of thesis ..Explaining irredentism: the case of Hungary and its transborder minorities in Romania and Slovakia............................................................................................................................. ....................................................................................... Degree..PhD in Government............... This thesis seeks to explain irredentism by identifying the set of variables that determine its occurrence. To do so it provides the necessary definition and comparative analytical framework, both lacking so far, and thus establishes irredentism as a field of study in its own right. The thesis develops a multi-variate explanatory model that is generalisable yet succinct. -

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 100% (Korea) How to cry (ミヌ盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5005 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415958 100% (Korea) How to cry (ロクヒョン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5006 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415970 100% (Korea) How to cry (ジョンファン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5007 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415972 100% (Korea) How to cry (チャンヨン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5008 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415974 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you (A) OKCK5011 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655024 100% (Korea) Song for you (B) OKCK5012 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655026 100% (Korea) Song for you (C) OKCK5013 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655027 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) -

Democracy Index 2010 Democracy in Retreat a Report from the Economist Intelligence Unit

Democracy index 2010 Democracy in retreat A report from the Economist Intelligence Unit www.eiu.com Democracy index 2010 Democracy in retreat The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Index of Democracy 2010 Democracy in retreat This is the third edition of the Economist Intelligence Unit’s democracy index. It reflects the situation as of November 2010. The first edition, published in The Economist’sThe World in 2007, measured the state of democracy in September 2006 and the second edition covered the situation towards the end of 2008. The index provides a snapshot of the state of democracy worldwide for 165 independent states and two territories—this covers almost the entire population of the world and the vast majority of the world’s independent states (micro states are excluded). The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Index of Democracy is based on five categories: electoral process and pluralism; civil liberties; the functioning of government; political participation; and political culture. Countries are placed within one of four types of regimes: full democracies; flawed democracies; hybrid regimes; and authoritarian regimes. Free and fair elections and civil liberties are necessary conditions for democracy, but they are unlikely to be sufficient for a full and consolidated democracy if unaccompanied by transparent and at least minimally efficient government, sufficient political participation and a supportive democratic political culture. It is not easy to build a sturdy democracy. Even in long-established ones, if not nurtured and protected, democracy can corrode. Democracy in decline The global record in democratisation since the start of its so-called third wave in 1974, and acceleration after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, has been impressive. -

GREAT BRITAIN, the SOVIET UNION and the POLISH GOVERNMENT in EXILE (1939-1945) Studies in Contemporary History

GREAT BRITAIN, THE SOVIET UNION AND THE POLISH GOVERNMENT IN EXILE (1939-1945) Studies in Contemporary History Volume 3 I. Rupieper, Hermann J. The Cuno Government and Reparations, 1922-1923: Politics and Economics. 1979, viii + 289. ISBN 90-247-2114-8. 2. Hirshfield, Claire. The Diplomacy of Partition: Britain, France and the Creation of Nigeria 1890-1898. 1979, viii + 234. ISBN 90-247-209<)-0. 3. Kacewicz, George V. Great Britain, the Soviet Vnion and the Polish Government in Exile 193~1945. 1979, xv + 252. ISBN 90-247-2096--6. G REA T BRITAIN, THE SOVIET UNION AND THE POLISH GOVERNMENT IN EXILE (1939-1945) by GEORGE V. KACEWICZ . ~ '. •. ~ . I979 MARTINUS NIJHOFF PUBLISHERS THE HAGUE/ BOSTON/LONDON The distribution of this book is handled by the following team of publisbers: for Ihe United Stoles "lid Canada Kluwer Boston, Inc. 160 Old Derby Street Hingbam, MA 0204) USA far 0/1 alher co ulllrit~ Kluwer Academic Publishers Group Di stribution Center P.O. Box)2l 3300 AH Dordrocht The Netherlands Libr ~ r y of Congress C~ l a l og in g in Publication D ata Kacewicz. George V Great Britain. the Soviet Union. and Ihe Polish Government in Exile (t939-1945) Bibliography: p. Includes index. I, World War, 1939-1945 - Go\'ernments in exile. 2. World War, 1939-1945 - Poland. 3. Poland -History - Occupation, 1939-1945. 4. Great Britain - Foreign re lations -Russia. 5. Russia _ Foreign relations - Great Britain. 6. World War. 1939-1945 - Diplomatic Hi story. I. Title. D81 0.G6K3l 1979 940.53'438 78- 31832 ISBN-13: 978-94-009-9274-0 c-ISBN-13 : 978-94-009-9272-6 001 : 10.1007/978-94-009-9272-6 Copyright 1979 by Mor linus Nijhoff Publishers br, The Hogue. -

NK Pro Ship Tracker

The New Pro When you’re working on the frontlines of the North Korea portfolio, you need far more than news coverage alone. WHO WE SERVE Government/Diplomacy Corporate/Finance News/Media Security/Military Research/Academia NGOs The ultimate resource for professionals working on North Korea While the DPRK is ‘unknowable’ to many, there is more information available about the country than ever. But identifying the key signals – where one statement, leadership change, or weapons test can change the course of the future – is becoming more challenging by the day. NK Pro cuts through the noise to serve those who need quality, reliability and timeliness the most: people on the frontlines of policy, business and research. “As someone who has followed and assessed developments in North Korea for many years, I can not recollect a time in the past few decades when interest was higher. News coverage has expanded exponentially but quantity is no substitute for quality. I have found NK Pro to be the best source for keeping me current on events, as well as in assisting my research.” William Newcomb, Former member of the UN Panel of Experts “In the 11 years of work training over 2,000 North Koreans in economic policy, business, entrepreneurship and infrastructure, I have depended on NK Pro as a rare source of reliable news on an issue plagued by agendas, misinformation, and rumors.” Geoffrey See, Founder, Choson Exchange “When you have too much information and when information is conflicting, the ground truth is the deciding factor. NK Pro provides its subscribers with that ground truth.