University of West Bohemia in Pilsen Faculty of Philosophy and Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nkorea's Twitter Account Hacked Amid Tension (Update) 4 April 2013, by Youkyung Lee

NKorea's Twitter account hacked amid tension (Update) 4 April 2013, by Youkyung Lee Hackers apparently broke into at least two of North sanctions against its nuclear program and joint Korea's government-run online sites Thursday, as military drills between the U.S. and South Korea. tensions rose on the Korean Peninsula. North and South have fired claims of cyberattacks The North's Uriminzokkiri Twitter and Flickr at each other recently. Last month computers froze accounts stopped sending out content typical of at six major South Korean companies—three banks that posted by the regime in Pyongyang, such as and three television networks—and North Korea's photos of North's leader Kim Jong Un meeting with Internet shut down. military officials. Meanwhile, the website for the U.S. forces Instead, a picture posted Thursday on the North's stationed in South Korea has been closed since Flickr site shows Kim's face with a pig-like snout Tuesday and their public affairs office said Friday and a drawing of Mickey Mouse on his chest. that the problem does not have to do with any Underneath, the text reads: "Threatening world hacking. peace with ICBMs and Nuclear weapons/Wasting money while his people starve to death." "Initial assessments indicate it is the result of an internal server issue," it said on the website without Another posting says "We are Anonymous" in elaboration. white letters against a black background. Anonymous is a name of a hacker activist group. A Copyright 2013 The Associated Press. All rights statement purporting to come from the attackers reserved. -

Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. Bennett C O R P O R A T I O N NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. -

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2014-20439 Doc No. C05771047 Date: 08/31/2015 RELEASE in PART B6 From: Sent: To

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2014-20439 Doc No. C05771047 Date: 08/31/2015 RELEASE IN PART B6 From: PIR <preines Sent: Monday, August 16, 2010 11:48 PM To: Cc: Huma Abedin; CDM; Jake Sullivan Subject: "minister in a skirt" http://mobile.nytimes.com/a rticle?a=644869 North Korea Takes to Twitter and YouTube By CHOE SANG-HUN The New York Times August 17, 2010 SEOUL, South Korea - North Korea has taken its propaganda war against South Korea and the United States to a new frontier: YouTube and Twitter. In the last month, North Korea has posted a series of video clips on YouTube brimming with satire and vitriol against leaders in South Korea and the United States. In one clip, it called Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton a "minister in a skirt" and Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates a "war maniac," while depicting the South Korean defense minister, Kim Tae-young, as a "servile dog" that likes to be patted by "its American master." Such language used to be standard in North Korea's cold-war-era propaganda. Its revival is testimony to the increased chill in relations between the Koreas in recent months. In the past week, North Korea also began operating a Twitter account under the name uriminzok, or "our nation." Both the Twitter and YouTube accounts are owned by a user named "uriminzokkiri." The Web site www.uriminzokkiri.com is run by the Committee for the Peaceful Reunification of Korea, a propaganda agency in Pyongyang. Lee Jong-joo, a spokeswoman for the Unification Ministry in Seoul, said, "It is clear that these accounts carry the same propaganda as the North's official news media, but we have not been able to find out who operates them." The two Koreas agreed to stop their psychological war after their first summit meeting in 2000. -

Family, Mobile Phones, and Money: Contemporary Practices of Unification on the Korean Peninsula Sandra Fahy 82 | Joint U.S.-Korea Academic Studies

81 Family, Mobile Phones, and Money: Contemporary Practices of Unification on the Korean Peninsula Sandra Fahy 82 | Joint U.S.-Korea Academic Studies Moving from the powerful and abstract construct of ethnic homogeneity as bearing the promise for unification, this chapter instead considers family unity, facilitated by the quotidian and ubiquitous tools of mobile phones and money, as a force with a demonstrated record showing contemporary practices of unification on the peninsula. From the “small unification” (jageun tongil) where North Korean defectors pay brokers to bring family out, to the transmission of voice through the technology of mobile phones illegally smuggled from China, this paper explores practices of unification presently manifesting on the Korean Peninsula. National identity on both sides of the peninsula is usually linked with ethnic homogeneity, the ultimate idea of Koreanness present in both Koreas and throughout Korean history. Ethnic homogeneity is linked with nationalism, and while it is evoked as the rationale for unification it has not had that result, and did not prevent the ideological nationalism that divided the ethnos in the Korean War.1 The construction of ethnic homogeneity evokes the idea that all Koreans are one brethren (dongpo)—an image of one large, genetically related extended family. However, fissures in this ideal highlight the strength of genetic family ties.2 Moving from the powerful and abstract construct of ethnic homogeneity as bearing the promise for unification, this chapter instead considers family unity, facilitated by the quotidian and ubiquitous tools of mobile phones and money, as a force with a demonstrated record showing “acts of unification” on the peninsula. -

Special Report No

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 490 | FEBRUARY 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE w w w .usip.org North Korea in Africa: Historical Solidarity, China’s Role, and Sanctions Evasion By Benjamin R. Young Contents Introduction ...................................3 Historical Solidarity ......................4 The Role of China in North Korea’s Africa Policy .........7 Mutually Beneficial Relations and Shared Anti-Imperialism..... 10 Policy Recommendations .......... 13 The Unknown Soldier statue, constructed by North Korea, at the Heroes’ Acre memorial near Windhoek, Namibia. (Photo by Oliver Gerhard/Shutterstock) Summary • North Korea’s Africa policy is based African arms trade, construction of owing to African governments’ lax on historical linkages and mutually munitions factories, and illicit traf- sanctions enforcement and the beneficial relationships with African ficking of rhino horns and ivory. Kim family regime’s need for hard countries. Historical solidarity re- • China has been complicit in North currency. volving around anticolonialism and Korea’s illicit activities in Africa, es- • To curtail North Korea’s illicit activ- national self-reliance is an under- pecially in the construction and de- ity in Africa, Western governments emphasized facet of North Korea– velopment of Uganda’s largest arms should take into account the histor- Africa partnerships. manufacturer and in allowing the il- ical solidarity between North Korea • As a result, many African countries legal trade of ivory and rhino horns and Africa, work closely with the Af- continue to have close ties with to pass through Chinese networks. rican Union, seek cooperation with Pyongyang despite United Nations • For its part, North Korea looks to China, and undercut North Korean sanctions on North Korea. -

North Korea's Nuclear Weapons Development and Diplomacy

North Korea’s Nuclear Weapons Development and Diplomacy Larry A. Niksch Specialist in Asian Affairs January 5, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33590 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress North Korea’s Nuclear Weapons Development and Diplomacy Summary Since August 2003, negotiations over North Korea’s nuclear weapons programs have involved six governments: the United States, North Korea, China, South Korea, Japan, and Russia. Since the talks began, North Korea has operated nuclear facilities at Yongbyon and apparently has produced weapons-grade plutonium estimated as sufficient for five to eight atomic weapons. North Korea tested a plutonium nuclear device in October 2006 and apparently a second device in May 2009. North Korea admitted in June 2009 that it has a program to enrich uranium; the United States had cited evidence of such a program since 2002. There also is substantial information that North Korea has engaged in collaborative programs with Iran and Syria aimed at producing nuclear weapons. On May 25, 2009, North Korea announced that it had conducted a second nuclear test. On April 14, 2009, North Korea terminated its participation in six party talks and said it would not be bound by agreements between it and the Bush Administration, ratified by the six parties, which would have disabled the Yongbyon facilities. North Korea also announced that it would reverse the ongoing disablement process under these agreements and restart the Yongbyon nuclear facilities. Three developments -

North Korean Identity As a Challenge to East Asia's Regional Order

Korean Soc Sci J (2017) 44:51–71 North Korean Identity as a Challenge to East Asia’s Regional Order Leif-Eric Easley Received: 9 May 2017 / Accepted: 31 May 2017 / Published online: 9 June 2017 Ⓒ Korean Social Science Research Council 2017 Introduction North Korea presents serious complications for East Asia’s regional order, and yet its identity is subject to frequent oversimplification. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK or North Korea) is often in the headlines for its nuclear weapons and missile programs and for its violations of human rights.1 Media reports typically depict North Korea as an otherworldly hermit kingdom ruled by a highly caricatured Kim regime. This article seeks to deepen the conversation about North Korea’s political characteristics and East Asia’s regional architecture by addressing three related questions. First, how has North Korea challenged the regional order, at times driving some actors apart and others together? How are these trends explained by and reflected in North Korean national identity, as articulated by the Kim regime and as perceived in the region? Finally, what academic and policy-relevant implications are offered by the interaction of North Korean identity and regional order? To start, measuring national identity is a difficult proposition (Abdelal, et al., 2009). Applying the concepts of national identity and nationalism to North Korea are complicated by analytical problems in separating the nation, and especially the state, from the Kim regime. This study chooses to focus on “identity” rather than “nationalism” because “North Korean nationalism” implies a certain ideology that contrasts to the nationalisms of the Republic of Korea (ROK or South Korea), Japan or China. -

Adam Cathcart, Christopher Green, and Steven Denney

Articles How Authoritarian Regimes Maintain Domain Consensus: North Korea’s Information Strategies in the Kim Jong-un Era Adam Cathcart, Christopher Green, and Steven Denney Te Review of Korean Studies Volume 17 Number 2 (December 2014): 145-178 ©2014 by the Academy of Korean Studies. All rights reserved. 146 Te Review of Korean Studies Pyongyang’s Strategic Shift North Korea is a society under constant surveillance by the apparatuses of state, and is a place where coercion—often brutal—is not uncommon.1 However, this is not the whole story. It is inaccurate to say that the ruling hereditary dictatorship of the Kim family exerts absolute control purely by virtue of its monopoly over the use of physical force. The limitations of state coercion have grown increasingly evident over the last two decades. State-society relations in North Korea shifted drastically when Kim Jong-il came to power in the 1990s. It was a time of famine, legacy politics, state retrenchment, and the rise of public markets; the state’s coercive abilities alternated between dissolution and coalescence as the state sought to co-opt and control the marketization process, a pattern which continued until Kim Jong-il’s death in 2011 (Kwon and Chung 2012; Hwang 1998; Hyeon 2007; Park 2012). Those relations have moved still further under Kim Jong- un.2 Tough Kim’s rise to the position of Supreme Leader in December 2011 did not precipitate—as some had hoped—a paradigmatic shift in economic or political approach, the state has been extremely active in the early years of his era, responding to newfound domestic appreciation of North Korea’s situation in both the region and wider world. -

Wrth2016intradiosuppl2 A16

This file is a supplement to the 2016 edition of World Radio TV Handbook, and summarises the changes to the schedules printed in the book resulting from the implementation of the 2016 “A” season schedules. Contact details and other information about the stations shown in this file can be found in the International Radio section of WRTH 2016. If you haven’t yet got your copy, the book can be ordered from Amazon, your nearest bookstore or directly from our website at www.wrth.com/_shop WRTH INTERNATIONAL RADIO SCHEDULES - MAY 2016 Notes for the International Radio section Country abbreviation codes are shown after the country name. The three-letter codes after each frequency are transmitter site codes. These, and the Area/Country codes in the Area column, can be decoded by referring to the tables in the at the end of the file. Where a frequency has an asterisk ( *) etc. after it, see the ‘ KEY ’ section at the end of the sched - ule entry. The following symbols are used throughout this section: † = Irregular transmissions/broadcasts; ‡ = Inactive at editorial deadline; ± = variable frequency; + = DRM (Digital Radio Mondiale) transmission. ALASKA (ALS) ANGOLA (AGL) KNLS INTERNATIONAL (Rlg) ANGOLAN NATIONAL RADIO (Pub) kHz: 7355, 9655, 9920, 11765, 11870 kHz: 945 Summer Schedule 2016 Summer Schedule 2016 Chinese Days Area kHz English Days Area kHz 0800-1200 daily EAs 9655nls 2200-2300 daily SAf 945mul 1300-1400 daily EAs 9655nls, 9920nls French Days Area kHz 1400-1500 daily EAs 7355nls 2100-2200 daily SAf 945mul English Days Area kHz Lingala -

3 DX MAGAZINE No. 2

2 - 2004 All times mentioned in this DX MAGAZINE are UTC - Alle Zeiten in diesem DX MAGAZINE sind UTC Staff of WORLDWIDE DX CLUB: PRESIDENT AND CHIEF EDITOR ..C WWDXC Headquarters, Michael Bethge, Postfach 12 14, D-61282 Bad Homburg, Germany B daytime +49-6102-2861, B evening/weekend +49-6172-390918 F +49-6102-800999 V E-Mail: [email protected] BROADCASTING NEWS EDITOR . C Dr. Jürgen Kubiak, Goltzstrasse 19, D-10781 Berlin, Germany E-Mail: [email protected] LOGBOOK EDITOR .............C Ashok Kumar Bose, Apt. #421, 3420 Morning Star Drive, Mississauga, ON, L4T 1X9, Canada V E-Mail: [email protected] QSL CORNER EDITOR ..........C Richard Lemke, 60 Butterfield Crescent, St. Albert, Alberta, T8N 2W7, Canada V E-Mail: [email protected] TOP NEWS EDITOR (Internet) ....C Wolfgang Büschel, Hoffeld, Sprollstrasse 87, D-70597 Stuttgart, Germany V E-Mail: [email protected] TREASURER & SECRETARY .....C Karin Bethge, Urseler Strasse 18, D-61348 Bad Homburg, Germany NEWCOMER SERVICE OF AGDX . C Hobby-Beratung, c/o AGDX, Postfach 12 14, D-61282 Bad Homburg, Germany (please enclose return postage) Each of the editors mentioned above is self-responsible for the contents of his composed column. Furthermore, we cannot be responsible for the contents of advertisements published in DX MAGAZINE. We have no fixed deadlines. Contributions may be sent either to WWDXC Headquarters or directly to our editors at any time. If you send your contributions to WWDXC Headquarters, please do not forget to write all contributions for the different sections on separate sheets of paper, so that we are able to distribute them to the competent section editors. -

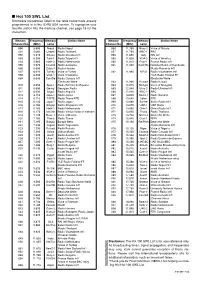

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

Surviving Through the Post-Cold War Era: the Evolution of Foreign Policy in North Korea

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal Title Surviving Through The Post-Cold War Era: The Evolution of Foreign Policy In North Korea Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4nj1x91n Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, 21(2) ISSN 1099-5331 Author Yee, Samuel Publication Date 2008 DOI 10.5070/B3212007665 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction “When the establishment of ‘diplomatic relations’ with south Korea by the Soviet Union is viewed from another angle, no matter what their subjective intentions may be, it, in the final analysis, cannot be construed otherwise than openly joining the United States in its basic strategy aimed at freezing the division of Korea into ‘two Koreas,’ isolating us internationally and guiding us to ‘opening’ and thus overthrowing the socialist system in our country [….] However, our people will march forward, full of confidence in victory, without vacillation in any wind, under the unfurled banner of the Juche1 idea and defend their socialist position as an impregnable fortress.” 2 The Rodong Sinmun article quoted above was published in October 5, 1990, and was written as a response to the establishment of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union, a critical ally for the North Korean regime, and South Korea, its archrival. The North Korean government’s main reactions to the changes taking place in the international environment during this time are illustrated clearly in this passage: fear of increased isolation, apprehension of external threats, and resistance to reform. The transformation of the international situation between the years of 1989 and 1992 presented a daunting challenge for the already struggling North Korean government.