Rethinking the Somali State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Awdal Region - Completed Activities Jan-Dec 2012 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Lawya ! ! ! Caddo 43°0'E 43°30'E 44°0'E ! ! ! ! El Qori Sacadiin ! ! ! Bariisle ( Island) ! ! !

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! WASH CLUSTER - Awdal Region - Completed Activities Jan-Dec 2012 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Lawya ! ! ! Caddo 43°0'E 43°30'E 44°0'E ! ! ! ! El Qori Sacadiin ! ! ! Bariisle ( Island) ! ! ! ! ! Muliyo ! ! ! ! ! Zeylac ! ! ! ! ! ! Toqos!hi ! Zeylac ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Waraabood ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A!WDAL ! ! ! ! Doon Jaglaleh ! ! ! ! ! Caasha ! ! ! ! ! ! Caddo ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Xirsi ! Bow! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Odawaa ! ! ! ! ZEYLAC !Dari ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! N N ! ' ' ! ! ! ! ! 0 0 ! ! ! ° ° ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 1 Cali Ceel ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 Harag Jiid 1 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !Weeci Gaal ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !Haren ! ! ! Dudub ! ! ! Laan Cawaale ! Heensa Asa ! Laan Shinbirood ! ! ! ! ! ! Qumbo ! !Guutooyinka ! Camuud ! ! ! Wareen ! ! ! C!ulus ! ! ! ! Fulla ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! !Iskudarka ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! Cammuud Culus !! ! ! ! ! Bulo ! Sh.Ciise ! ! ! ! ! Karuure ! ! !Xareed ! Heemaal ! ! ! ! Xidhxid Galbeed ! ! !Cadde ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Garaaca ! ! ! X!oore ! ! ! Lughaye ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !Bullo Qoxle Lughaye ! ! !Xajiinle ! ! !Hadhwanaag ! Beeyo ! ! ! Beeyo ! ! ! Maame! !Liiban Macaan ! HEAL LUGHAYE ! ! Nuur ! ! Carmaale ! ! G!ahayr !! ! ! Odawaa ! ! ! ! ! Ido-Cadeys !Geerisa Heemaal ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Dheere Hadeytacawl Biyo ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Cas!e !! ! ! Hadayta ! ! ! Haydeeta ! ! Baxarsaas Heemaal ! !Xussein ! ! ! Weyn ! Baxara Kalawle ! ! Sheikh Awaare Biyo-Cas -

September 29, 2005 Parliamentary Election Assessment Report

International Republican Institute Suite 700 1225 Eye St., NW Washington, D.C. 20005 (202) 408-9450 (202) 408-9462 FAX www.iri.org International Republican Institute Somaliland September 29, 2005 Parliamentary Election Assessment Report Table of Contents Map of Somaliland……………………………………………………………………..….2 Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………….....3 I. Background Information.............................................................................................…..5 II. Legal and Administrative Framework………………………………..………..……….8 III. Pre-Election Period……………. …...……………………………..…………...........12 IV. Election Day…………...…………………………………………………………….18 V. Post-Election Period and Results.…………………………………………………….27 VI. Findings and Recommendations……………………………………………………..33 VII. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………..38 Appendix A: Voting Results in 2005 Presidential Elections…………………………….39 Appendix B: Voting Results in 2003 Presidential Elections…………………………….41 Appendix C: Voting Results in 2002 Local Government Elections……………………..43 Appendix D: Voting Trends……………………………………………………………..44 IRI – Somaliland September 29, 2005 Parliamentary Election Assessment Report 1 Map of Somaliland IRI – Somaliland September 29, 2005 Parliamentary Election Assessment Report 2 Executive Summary Background The International Republican Institute (IRI) has conducted programs in Somaliland since 2002 with the support of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the U.S. Department of State, and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). IRI’s Somaliland -

This Action Is Funded by the European Union

EN This action is funded by the European Union ANNEX 7 of the Commission Decision on the financing of the Annual Action Programme 2018 – part 3 in favour of Eastern and Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean to be financed from the 11th European Development Fund Action Document for Somalia Regional Corridors Infrastructure Programme (SRCIP) 1. Title/basic act/ Somalia Regional Corridors Infrastructure Programme (SRCIP) CRIS number RSO/FED/040-766 financed under the 11th European Development Fund (EDF) 2. Zone East Africa, Somalia benefiting from The action shall be carried out in Somalia, in the following Federal the Member States (FMS): Galmudug, Hirshabelle, Jubaland, Puntland action/location 3. Programming 11th EDF – Regional Indicative Programme (RIP) for Eastern Africa, document Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean (EA-SA-IO) 2014-2020 4. Sector of Regional economic integration DEV. Aid: YES1 concentration/ thematic area 5. Amounts Total estimated cost: EUR 59 748 500 concerned Total amount of EDF contribution: EUR 42 000 000 This action is co-financed in joint co-financing by: Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) for an amount of EUR 3 500 000 African Development Fund (ADF) 14 Transitional Support Facility (TSF) Pillar 1: EUR 12 309 500 New Partnership for Africa's Development Infrastructure Project Preparation Facility (NEPAD-IPPF): EUR 1 939 000 6. Aid Project Modality modality(ies) Indirect management with the African Development Bank (AfDB). and implementation modality(ies) 7 a) DAC code(s) 21010 (Transport Policy and Administrative Management) - 8% 21020 (Road Transport) - 91% b) Main 46002 – African Development Bank (AfDB) Delivery Channel 1 Official Development Aid is administered with the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective. -

Survey of British Colonial Development Policy

No. E 68-A RESTRICTED r:;: ONE '\f ..- tf\rhi.§..l report is restricted to use within the Bank Public Disclosure Authorized INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT Public Disclosure Authorized SURVEY OF BRITISH COLONIAL DEVELOPMENT POLICY November 9. 1949 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Economic Department Prepared by: B. King TABLE OF CONTE.t-J'TS Page No. I. PREFACE (and Map) • • • • • • • • • t • • .. .. i II. SPi!IMARY • • •••• .. .. ., . , . · .. iv , . III. THE COLONIES UP TO 1940' •• .. .. .. .. • • • 1 TJi.BLES I '& II • .'. .. • • • • • • • • 8 . IV. THE COLONIES SINCE, 1940 ••• • • • • • • • • 10 TABlES III to VI • • • 0 • • • • • • • • 29 APPElIIDIX - THE CURRENCY SYSTEMS OF' THE cOtOlUAL EI'!PlRE .....,,,.,. 34 (i) I. PREFACE The British Colonial :empire is a sO!!lm-:hat loose expression embracing some forty dependencies of the United Kingdom. For the purposes of this paper the term vdll be used to cover all dependencies administered through the Colonial Office on December 31" 1948 cmd" in addition, the three :30uth African High Cowmission territories, which are under the control of the Commonwealth Relations Office. This definition is adopted" since its scope is the same as that of the various Acts of Parliament passed since lSll.~O to Dovcloptx;nt promote colomal development, including the Overseas Resourceshct y::rLcl1 established the Colonial Development Corporation. A full list of the~e ter:-itories 17ill be found in the list following. It [;hould be noted th'lt in conform..i.ty vri th the provisions of the recent Acts vIhieh apply only to flcolonies not possessing responsible govermnent,uYthe definition given above excludes the self-governing colony of Southern :Ehodesia, v(nose rela- tions with the United Kinr;dom are conducted through the Co:nmonlrealth Relations Office. -

Integrated Nutrition and Mortality Smart Survey

INTEGRATED NUTRITION AND MORTALITY SMART SURVEY REPORT ELBARDE DISTRICT, BAKOOL REGION, SOMALIA NOVEMBER 2020 I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Action against Hunger (ACF), would like to acknowledge all the support provided during the preparation, training and field activities of the survey, which includes but not limited to; ➢ Technical and logistical support provided by Elbarde Municipality and the Ministry of Health in South West state of Somalia, facilitation during the training and field work. ➢ We would like to acknowledge the roles of the assessment teams including the team leaders, enumerators and community field guides and all the parents/caregivers who provided valuable information to the survey team, and participated the assessment. ➢ Assessment Information Management Working Group (AIMWG) members for the technical inputs and validations. ➢ Appreciation also goes to SIDA, for the generous financial supports to conduct this nutrition and mortality survey. Statement on Copyright © Action Against Hunger Unless otherwise indicated, reproduction is authorized on condition that the source is credited. If reproduction or use of texts and visual materials (sound, images, software, etc.) is subject to prior authorization, such authorization will render null and void the above-mentioned general authorization and will clearly indicate any restrictions on use. II Table of contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................. II Table of contents .................................................................................................................................... -

Democratic Republic of Congo Constitution

THE CONSTITUTION OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO, 2005 [1] Table of Contents PREAMBLE TITLE I GENERAL PROVISIONS Chapter 1 The State and Sovereignty Chapter 2 Nationality TITLE II HUMAN RIGHTS, FUNDAMENTAL LIBERTIES AND THE DUTIES OF THE CITIZEN AND THE STATE Chapter 1 Civil and Political Rights Chapter 2 Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Chapter 3 Collective Rights Chapter 4 The Duties of the Citizen TITLE III THE ORGANIZATION AND THE EXERCISE OF POWER Chapter 1 The Institutions of the Republic TITLE IV THE PROVINCES Chapter 1 The Provincial Institutions Chapter 2 The Distribution of Competences Between the Central Authority and the Provinces Chapter 3 Customary Authority TITLE V THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL TITLE VI DEMOCRACY-SUPPORTING INSTITUTIONS Chapter 1 The Independent National Electoral Commission Chapter 2 The High Council for Audiovisual Media and Communication TITLE VII INTERNATIONAL TREATIES AND AGREEMENTS TITLE VIII THE REVISION OF THE CONSTITUTION TITLE IX TRANSITORY AND FINAL PROVISIONS PREAMBLE We, the Congolese People, United by destiny and history around the noble ideas of liberty, fraternity, solidarity, justice, peace and work; Driven by our common will to build in the heart of Africa a State under the rule of law and a powerful and prosperous Nation based on a real political, economic, social and cultural democracy; Considering that injustice and its corollaries, impunity, nepotism, regionalism, tribalism, clan rule and patronage are, due to their manifold vices, at the origin of the general decline -

Briefing Paper

NEW ISSUES IN REFUGEE RESEARCH Working Paper No. 65 Pastoral society and transnational refugees: population movements in Somaliland and eastern Ethiopia 1988 - 2000 Guido Ambroso UNHCR Brussels E-mail : [email protected] August 2002 Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees CP 2500, 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.unhcr.org These working papers provide a means for UNHCR staff, consultants, interns and associates to publish the preliminary results of their research on refugee-related issues. The papers do not represent the official views of UNHCR. They are also available online under ‘publications’ at <www.unhcr.org>. ISSN 1020-7473 Introduction The classical definition of refugee contained in the 1951 Refugee Convention was ill- suited to the majority of African refugees, who started fleeing in large numbers in the 1960s and 1970s. These refugees were by and large not the victims of state persecution, but of civil wars and the collapse of law and order. Hence the 1969 OAU Refugee Convention expanded the definition of “refugee” to include these reasons for flight. Furthermore, the refugee-dissidents of the 1950s fled mainly as individuals or in small family groups and underwent individual refugee status determination: in-depth interviews to determine their eligibility to refugee status according to the criteria set out in the Convention. The mass refugee movements that took place in Africa made this approach impractical. As a result, refugee status was granted on a prima facie basis, that is with only a very summary interview or often simply with registration - in its most basic form just the name of the head of family and the family size.1 In the Somali context the implementation of this approach has proved problematic. -

Fact Sheet V4

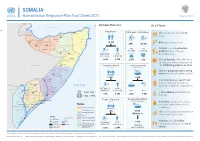

SOMALIA Humanitarian Response Plan Fact Sheet 2021 February 2021 Somalia Overview At a Glance p p! G U L F O F A D E N Caluula Lorem ipsum !p ! Qandala D J I B O U T I Zeylac !p! p Population !pLaasqoray Refugees Returnees Bossaso 69% live on less than $1.90 Awdal ! Ceerigaabo p Lughaye !!p p p a day p! pp Berbera p ! Baki Sanaag ! Iskushuban Borama Woqooyi Ceel Afweyn !! Galbeed !p Sheikh ! Bari p 12.3M Gebiley 40% adult literacy rate p ! p p p Bandarbayla 28K 109.9K !!p !p p ! Odweyne ! Burco ! Qardho pp! ! Hargeysa p Xudun ! !Taleex p Caynabo !p #OF 10,300 recorded protection Togdheer Sool p #OF IDP SITES Laas Caanood PARTNERS incidents from January- p! ! !p p Buuhoodle ! ! Garowe p INTERNALLY NON- December 2020 p p ! DISPLACED DISPLACED Eyl Nugaal ! Burtinle 2.6M 9.7M 2,472 363 20% of Somalis will suffer from !Jariiban ! Galdogob the direct or indirect impacts of Gaalkacyo E T H I O P I A !!p People in Need Food insecurity the COVID19 pandemic in 2021 (2021) (Jan-Jun 2021) ! ! Cadaado Mudug p Cabudwaaq 182,000 pregnant and lactating Dhuusamarreeb !! p women are acutely malnourished Hobyo Galgaduud p ! pp p 5.9M 2.6M p ! Belet Weyne Ceel Buur Ceel Barde !p! Xarardheere ! ! ! 1 in 1,000 women aged 15-49 ! Hiraan p Yeed years in Somalia dies due to ! Bakool Xudur p !!p Doolow ! Ceel Dheer Indian Ocean Bulo Burto pregnancy-related complications Luuq Tayeeglow ! ! ! p! ! Waajid !Adan Yabaal Belet Xaawo p NON- p INTERNALLY K E N Y A Garbahaarey Jalalaqsi !! ! DISPLACED DISPLACED IPC3 IPC4 !Berdale Baidoa Middle ! Gedo !p p Shabelle 2021 -

CLAIMING the EASTERN BORDERLANDS After the 1997

CHAPTER SEVEN CLAIMING THE EASTERN BORDERLANDS After the 1997 Hargeysa Conference, the Somaliland state apparatus consolidated. It deepened, as the state realm displaced governance arrangements overseen by clan elders. And it broadened, as central government control extended geographically from the capital into urban centres such as Borama in the west and Bur’o in the east. In the areas east of Bur’o government was far less present or efffective, especially where non-Isaaq clans traditionally lived. Erigavo, the capital of Sanaag Region, which was shared by the Habar Yunis, the Habar Ja’lo, the Warsengeli and the Dhulbahante, was fijinally brought under formal government control in 1997, after Egal sent a delegation of nine govern- ment ministers originating from the area to sort out local government with the elders and political actors on the ground. After fijive months of negotiations, the president was able to appoint a Mayor for Erigavo and a Governor for Sanaag.1 But east of Erigavo, in the area inhabited by the Warsengeli, any claim to governance from Hargeysa was just nominal.2 The same was true for most of Sool Region inhabited by the Dhulbahante. Eastern Sanaag and Sool had not been Egal’s priority. The president did not strictly need these regions to be under his military control in order to preserve and consolidate his position politically or in terms of resources. The port of Berbera was vital for the economic survival of the Somaliland government. Erigavo and Las Anod were not. However, because the Somaliland government claimed the borders of the former British protec- torate as the borders of Somaliland, Sanaag and Sool had to be seen as under government control. -

Surviving Through the Post-Cold War Era: the Evolution of Foreign Policy in North Korea

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal Title Surviving Through The Post-Cold War Era: The Evolution of Foreign Policy In North Korea Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4nj1x91n Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, 21(2) ISSN 1099-5331 Author Yee, Samuel Publication Date 2008 DOI 10.5070/B3212007665 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction “When the establishment of ‘diplomatic relations’ with south Korea by the Soviet Union is viewed from another angle, no matter what their subjective intentions may be, it, in the final analysis, cannot be construed otherwise than openly joining the United States in its basic strategy aimed at freezing the division of Korea into ‘two Koreas,’ isolating us internationally and guiding us to ‘opening’ and thus overthrowing the socialist system in our country [….] However, our people will march forward, full of confidence in victory, without vacillation in any wind, under the unfurled banner of the Juche1 idea and defend their socialist position as an impregnable fortress.” 2 The Rodong Sinmun article quoted above was published in October 5, 1990, and was written as a response to the establishment of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union, a critical ally for the North Korean regime, and South Korea, its archrival. The North Korean government’s main reactions to the changes taking place in the international environment during this time are illustrated clearly in this passage: fear of increased isolation, apprehension of external threats, and resistance to reform. The transformation of the international situation between the years of 1989 and 1992 presented a daunting challenge for the already struggling North Korean government. -

The Role of Education in Taming Authoritarian Attitudes

The Role of Education in Taming Authoritarian Attitudes WITH A FOREWORD BY JOHN J. DEGIOIA, PRESIDENT GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY Anthony P. Carnevale Nicole Smith Lenka Dražanová Artem Gulish Kathryn Peltier Campbell 2020 Center on Education and the Workforce McCourt School of Public Policy Reprint permissions [TK] Reprint Permission The Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce carries a Creative Commons license, which permits noncommercial reuse of any of our content when proper attribution is provided. You are free to copy, display, and distribute our work, or include our content in derivative works, under the following conditions: Attribution: You must clearly attribute the work to the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce and provide a print or digital copy of the work to [email protected]. Our preference is to cite figures and tables as follows: Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, The Role of Education in Taming Authoritarian Attitudes, 2020. Noncommercial Use: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Written permission must be obtained from the owners of the copy/literary rights and from Georgetown University for any publication or commercial use of reproductions. Approval: If you are using one or more of our available data representations (figures, charts, tables, etc.), please visit our website at cew.georgetown.edu/publications/reprint- permission for more information. For the full legal code of this Creative Commons license, please visit creativecommons.org. Email [email protected] with any questions. 2 THE ROLE OF EDUCATION IN TAMING AUTHORITARIAN ATTITUDES The Role of Education in Taming Authoritarian Attitudes WITH A FOREWORD BY JOHN J.