1338.1 .R813 9.REFERENCE ORGANIZATION (130) Cornell 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SMP Negeri 51 Bandung Mata Pelajaran : Prakarya/Budidaya

RENCANA PELAKSANAAN PEMBELAJARAN Sekolah : SMP Negeri 51 Bandung Mata Pelajaran : Prakarya/Budidaya Kelas/Semester : IX/1 Materi Pokok : Pengolahan Makanan berbahan dasar hasil Peternakan dan Perikanan Alokasi Waktu : 2 x 40’ A. Tujuan Pembelajaran Setelah melalui proses pembelajaran pesertadidik dapat memahami pengetahuan tentang prinsip perancangan, pembuatan, penyajian, dan pengemasan hasil peternakan (daging, telur, susu) dan perikanan (ikan, udang, cumi, rumput laut) menjadi makanan serta mampu mengolah bahan pangan hasil peternakan (daging, telur, susu) dan perikanan (ikan, udang, cumi, rumput laut) yang ada di wilayah setempat menjadi makanan serta menyajikan atau melakukan pengemasan dengan penuh rasa tanggung jawab, disiplin dan mandiri. B. Kegiatan Pembelajaran 1. Kegiatan Pendahuluan 1. Guru meminta kepada siswa untuk mengucapkan Basmallah sebelum pembelajaran dimulai dan dilanjutkan dengan berdo’a bersama orang tua. 2. Guru meminta kepada siswa untuk membuat kata-kata motivasi dan inspirasi untuk memberikan semangat dalaam melakukan proses pembelajaran. 3. Guru meminta kepada siswa untuk mempersiapkan buku pelajaran dan buku penunjang yang sesuai dengan materi yang akan dipelajari. 2. Kegiatan Inti Penentuan Projek ➢ Pada langkah ini, peserta didik menentukan tema/topik projek bersama orang tua. Peserta didik Bersama orang tua diberi kesempatan untuk memilih/menentukan projek yang akan dikerjakannya secara mandiri dengan catatan tidak menyimpang dari tema. Pada tahap ini peserta didik bekerja sama dengan orang tua untuk menentukan -

Discerning Coastal Ecotourism in Bira Island Hengky S.H

International Journal of Marine Science, 2018, Vol.8, No.6, 48-58 http://ijms.biopublisher.ca Research Article Open Access Discerning Coastal Ecotourism in Bira Island Hengky S.H. Universitas Bina Darma Kent Polytechnic, Indonesia Corresponding author email: [email protected] International Journal of Marine Science, 2018, Vol.8, No.6 doi: 10.5376/ijms.2018.08.0006 Received: 29 Dec., 2017 Accepted: 17 Jan., 2018 Published: 26 Jan., 2018 Copyright © 2018 Hengky, This is an open access article published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Preferred citation for this article: Hengky S.H., 2018, Discerning coastal ecotourism in Bira Island, International Journal of Marine Science, 8(6): 48-58 (doi: 10.5376/ijms.2018.08.0006) Abstract The Ministry of Tourism has created a 10-priority destination program in Indonesia. Pulau Seribu is one of the 10 destinations. Meanwhile, Bira Island is located in the Thousand Islands. To improve the performance of the Island, it is also necessary to increase the island of Bira. This mixed mode research, conducted for a year on the island of Bira to respond to the plans of the Ministry of Tourism. This study aims to discern Coastal Ecotourism in Bira Island, Indonesia. The results of data collection and tabulation show the existence of gap between the performances of the island at this time and expected. Ecotourism concept enhances CE performance on the island. In addition, the concept also creates jobs of women and anglers living along the coastline. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 259 3rd International Seminar on Tourism (ISOT 2018) The Reinforcement of Women's Role in Baluwarti as Part of Gastronomic Tourism and Cultural Heritage Preservation Erna Sadiarti Budiningtyas Dewi Turgarini Department English Language Catering Industry Management St. Pignatelli English Language Academy Indonesia University of Education Surakarta, Indonesia Bandung, Indonesia [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—Surakarta has the potential of gastronomic I. INTRODUCTION heritage tourism. The diversity of cuisine becomes the power of Cultural heritage is one of the attractions that is able to Surakarta as a tourist attraction. Municipality of Surakarta stated that their Long Term Development Plan for 2005-2025 will bring tourists. One of the cultural heritage is gastronomic develop cultural heritage tourism and traditional values, tourism, which is related to traditional or local food and historical tourism, shopping and culinary tourism that is part of beverage. Gastronomic tourism is interesting because tourists gastronomic tourism. The study was conducted with the aim to do not only enjoy the traditional or local food and beverage, identifying traditional food in Baluwarti along with its historical, but are expected to get deeper value. They can learn about the tradition, and philosophical values. This area is selected because history and philosophy of the food and beverage that is eaten it is located inside the walls of the second fortress. Other than and drink, the making process, the ingredients, and how to that, it is the closest area to the center of Kasunanan Palace. The process it. If tourism is seen as a threat to the preservation of participation of Baluwarti women in the activity of processing cultural heritage, gastronomic tourism shows that tourism is traditional food has become the part of gastronomic tourism and not a threat to conservation, but can preserve the food and cultural heritage preservation. -

Graduation Assignment

Vidyadhana, S. (2017, January 22). Kenapa Sih Anak Muda Indonesia Bersedia Terbebani Resepsi Pernikahan Mahal? Retrieved June 5, 2017, from VICE: https://www.vice.com/id_id/article/kenapa-sih-anak-muda-indonesia-bersedia-terbebani- resepsi-pernikahan-mahal Wahyuni, T. (2015, March 7). Makanan yang Paling Diincar Tamu di Pesta Pernikahan. Retrieved from CNN Indoneisa : http://www.cnnindonesia.com/gaya-hidup/20150307100907-262- 37404/makanan-yang-paling-diincar-tamu-di-pesta-pernikahan/ Wisnu, K. (2017, April 27). Mr. (B. Kusuma, Interviewer) 12. Appendices Appendix I: Products of Karunia Catering Buffet Packages Buffet Package A @ IDR 55,000 Soup Salad Vegetables Red Soup Caesar Salad Seafood Stir Fry Asparagus Soup Red Bean Salad Sukiyaki Beef Stir Fry Asparagus Corn Soup Marina Salad Crab with Broccoli Sauce Corn Soup Mix Vegetables Salad Szechuan Green Bean Waru Flower Soup Special Fruit Salad Squid and Broccoli Stir Fry Fish Meatball Soup Avocado Salad Sapo Seafood Mango Salad Broccoli and Squid Spicy Food Fish / Chicken Bistik Tongue Balado Special Kuluyuk Chicken Beef Rolade Meat Beef Balado Sweet and Sour Shrimps Beef Tongue Tongue Black Pepper Shrimp with Bread Crumb Betutu Chicken Beef Black Pepper Floured Fried Shrimp Roasted Chicken Roll Tongue Asem-asem Mayonnaise Shrimp Chicken Satay Tongue with Cheese Drum Stick Shrimp Meat Kalio Fish with Padang Sauce Lungs with Coconut Sour Salad Fish Fish with Bread Crumb 45 Bistik Dish served with sliced vegetables except for roasted chicken and satay Drink: Tea, soft drink / lemon tea -

Peraturan Kepala Badan Pengawas Obat Dan Makanan Republik Indonesia Nomor 1 Tahun 2015 Tentang Kategori Pangan

BADAN PENGAWAS OBAT DAN MAKANAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA PERATURAN KEPALA BADAN PENGAWAS OBAT DAN MAKANAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA NOMOR 1 TAHUN 2015 TENTANG KATEGORI PANGAN DENGAN RAHMAT TUHAN YANG MAHA ESA KEPALA BADAN PENGAWAS OBAT DAN MAKANAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA, Menimbang : a. bahwa kategori pangan merupakan suatu pedoman yang diperlukan dalam penetapan standar, penilaian, inspeksi, dan sertifikasi dalam pengawasan keamanan pangan; b. bahwa penetapan kategori pangan sebagaimana telah diatur dalam Keputusan Kepala Badan Pengawas Obat dan Makanan Nomor HK.00.05.42.4040 Tahun 2006 perlu disesuaikan dengan perkembangan ilmu pengetahuan dan teknologi serta inovasi di bidang produksi pangan; c. bahwa berdasarkan pertimbangan sebagaimana dimaksud dalam huruf a dan huruf b perlu menetapkan Peraturan Kepala Badan Pengawas Obat dan Makanan tentang Kategori Pangan; Mengingat : 1. Undang-Undang Nomor 8 Tahun 1999 tentang Perlindungan Konsumen (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1999 Nomor 42, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 3281); 2. Undang-Undang Nomor 36 Tahun 2009 tentang Kesehatan (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2009 Nomor 144, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 5063); 3. Undang-Undang Nomor 18 Tahun 2012 tentang Pangan (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2012 Nomor 227, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 5360); 4. Peraturan Pemerintah Nomor 69 Tahun 1999 tentang Label dan Iklan pangan (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1999 Nomor 131, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 3867); BADAN PENGAWAS OBAT DAN MAKANAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA - 2 - 5. Peraturan Pemerintah Nomor 28 Tahun 2004 tentang Keamanan, Mutu, dan Gizi Pangan (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2004 Nomor 107, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 4244); 6. Keputusan Presiden Nomor 103 Tahun 2001 tentang Kedudukan, Tugas, Fungsi, Kewenangan, Susunan Organisasi, dan Tata Kerja Lembaga Pemerintah Non Departemen sebagaimana telah beberapa kali diubah terakhir dengan Peraturan Presiden Nomor 3 Tahun 2013; 7. -

See Entire Menu

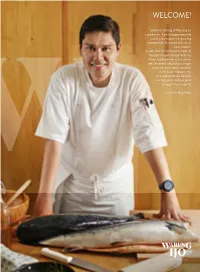

WELCOME! Selamat datang di Warung Ijo Excellence. Kami bangga menjadi salah satu bagian warga yang memberikan khasanah kuliner di kota Medan. Lebih dari 10 tahun kami hadir di tengah-tengah masyarakat ini, kami tidak pernah surut dalam ide dan kreasi dibalut rasa ingin melayani para tamu sekalian. Kami hadir dengan cita rasa unik berpadu dengan percampuran budaya lokal hingga internasional. Chef Melkhy Waas APPETIZER & SALAD Bakwan Sayur Keripik Pisang French Fries Pisang Goreng KERIPIK PISANG Tidak lengkap rasanya bersantai & mengobrol bersama teman-teman Anda tanpa ditemani keripik pisang kami. 16.5 NACHOSAVA Nachos Warung Ijo ini unik karena berbahan baku cassava chips yang merupakan khas BAKWAN SAYUR PISANG GORENG lokal kita. Gorengan sepanjang masa Hidangan klasik yang selalu yang berisi sayuran ini sangat menjadi andalan minum teh di 35.5 cocok menjadi cemilan sore hari. pembuka atau menemani FRENCH FRIES obrolan sore Anda. 22.5 (6 PCS) 25 18.5 (6 PCS) GORENGAN PLATTER 36.5 PEYEK 22.5 Cobbie Bitterballen Chicken Diablo BITTERBALLEN Warisan budaya kolonial Belanda ini, merupakan kudapan yang terdiri dari adonan daging, terigu dibalur tepung panir. 25 (6 PCS) COBBIE CHICKEN DIABLO Nikmati Salad campur versi Ayam bercita rasa pedas kami yang segar dan nikmat dan ditambah Torched Mayo ini sebagai hidangan pembuka tentunya akan memanjakan Anda. lidah Anda si penyuka hidangan ‘Spicy’. 49.5 27.5 SPECIALITY NASI IJO Signature baru Warung Ijo, Nasi berbumbu dan gurih, ditemani dengan Daging Gepuk Manis, Tempe Orek, Sambal Terong, Ikan Asin Cabai Hijau, Sambal Ati Ampela, Telur, dan Peyek. Pesan dan rasakan sensasi baru dari kami. 54.5 NASI AYAM BETUTU Terinspirasi masakan Bali, Warung Ijo menghadirkan campuran Nasi yang ditemani oleh Ayam Betutu, Sayur Bunga Pepaya, Cakalang Pampis, Telur, Teri Kacang dan Sambal Matah. -

Intention to Export of Small Firms in the Processed Foods Industry

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 100 International Conference of Organizational Innovation (ICOI 2019) INTENTION TO EXPORT OF SMALL FIRMS IN THE PROCESSED FOODS INDUSTRY Roos Kities Andadari (Satya Wacana Christian University) Diyanto (Satya Wacana Christian University) Email: [email protected] Abstract—In terms of numbers, the Indonesian utilized because of its huge size and untapped potential. economy is dominated by micro and small sized firms According to Walt (2007), producers from developing (MSEs), but their contributions to exporting are not countries tend to export commodities. For Indonesian significant. The government expects the contributions MSEs, involvement in international trade often of MSEs towards exporting to improve in the future. perceived as creates various problems due to differences The majority of Indonesian MSEs operate in the in language, culture, customs, and business methods processed food sector. A processed food is a consumer (Markoni, 2012). Export is a way to do good that requires adaptations to enter a foreign internationalization but many MSEs firms face problems such as the readiness of company resources, market as food fundamentally has cultural aspects. the inability to learn the conditions of destination This research aims to study small firms’ intention to countries, and fail to understand the obstacles or barriers export processed food. The data was collected through to enter to international markets. in-depth interviews with owners-managers of three small enterprises. The research found that the first Processed food is one of the export potentials that firm sells some of its products to foreign countries, were encouraged by the government to innovate and whereas the other two firms sell their products in the expand. -

Damai Restaurant Menu 2017 210417

Salads CAESAR SALAD 45 Romaine lettuce with caesar dressing, served with shaved parmesan cheese, beef bacon bits, foccacia crouton, and anchovies. Selada romaine dengan caesar dressing, disajikan dengan keju parmesan, bacon sapi, roti kering foccacia, dan ikan teri. FRESH GARDEN SALAD 40 Selection of seasonal leaves with sun dried tomatoes, bell peppers, and cucumbers with a choice of orange vinaigrette or Asian sesame dressing. Pilihan selada dengan tomat, paprika dan ketimun dengan pilihan dressing orange vinaigrette atau dressing wijen. ADDITIONAL TOPPING for Caesar and Fresh Garden Salad Salmon Steak | Daging salmon 40 Chicken breast | Fillet dada ayam 20 Angus fillet strips |Daging sapi Angus 45 GADO GADO ( Vegan) 45 Indonesian vegetable salad with tofus, rice cakes, and peanut sauce. Selada sayuran dengan tofu, lontong, dan saus kacang. SPICY CHICKEN SALAD 60 Grilled spicy marinated chicken, mix salads and apples, served with sesame passion fruit dressing. Daging ayam panggang pedas dengan selada dan apel, disajikan dengan dressing wijen markisa. SEAFOOD IN NICOISE STYLE SALAD 69 Salad of mixed fresh vegetables, seared scallops, salmons, tunas, and prawns with balsamic vinegar. Selada dengan sayuran segar, kerang, salmon, tuna, dan udang, dengan siraman cuka balsamic. Appetizers CAPELLINI 69 Cooked in tomato sauce with onions, garlics, capers, anchovies, and prawns. Pasta yang dimasak dengan saus tomat, bawang, capers, ikan teri, dan udang. SAMOSA 45 Deep fried vegetable infusion wrapped in asian fillow, served with yoghurt cucumber dressing and chilli aioli. Sayuran yang dibungkus oleh kulit pangsit lalu digoreng dan disajikan dengan dressing yoghurt ketimun dan mayones pedas. WASABI PRAWN 68 A dish by Chef Sam Leong's Deep fried battered prawns served with manggo salsa. -

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1. Latar Belakang Penelitian Era Informasi

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1. Latar Belakang Penelitian Era informasi yang sedang berkembang dengan cepat dan pesat dewasa ini, tentu akan berpengaruh terhadap perilaku manusia yang cenderung ingin mendapatkan segalanya dengan cepat dalam memenuhi kebutuhan dan keinginannya termasuk pemenuhan akan kebutuhan makanan dan minuman. Peningkatan pertumbuhan permintaan akan makanan, menjadi sebuah peluang bisnis tersendiri yang sangat besar. Setiap pelaku usaha dituntut untuk memiliki kepekaan terhadap setiap perubahan yang terjadi dan menempatkan orientasi terhadap kepuasan konsumen sebagai tujuan utama. Kepuasan pelanggan menurut Daryanto dan Setyobudi (2014:53) adalah perasaan puas yang didapatkan oleh pelanggan karena mendapatkan nilai dari pemasok, produsen atau penyedia jasa. Salah satu bisnis yang diperkirakan masih populer di tahun 2019 adalah bisnis waralaba, khususnya di sektor kuliner. Dengan kondisi peningkatan daya beli masyarakat golongan menengah, pasar kuliner menjadi sangat potensial. Saat ini dunia kuliner menjadi trend di kalangan masyarakat dan merupakan kebutuhan manusia yang paling utama. Persaingannya pun semakin ketat dan para pengusaha dituntut untuk menentukan perencanaan strategi pemasaran yang akan digunakannya untuk menghadapi persaingan saat ini. 1 Bisnis waralaba ayam gepuk merupakan olahan ayam goreng yang penyajiannya dipukul sampai gepeng. Sebelum digoreng, ayam direbus dulu sampai kering sehingga lebih gurih saat digoreng. Ayam ini disajikan lengkap dengan lalapan serta tambahan lainnya seperti tempe, tahu, maupun aneka sate seperti sate usus, sate kulit, dan sate ati. Menyantap ayam ini tak lengkap rasanya bila tidak ditemani sambal ulek yang khas rasanya. Hingga saat ini gerai Ayam Gepuk Pak Gembus tersebar di Jabodetabek, Jawa Barat, Jawa Tengah, Yogyakarta, Jawa Timur dan di luar Pulau Jawa seperti di Palembang, Bali, Riau, Batam, Balikpapan hingga Ambon. -

Menu the Ambassador Restaurant

BANDUNG PASTEUR Eats & treats Restaurant Menu The Ambassador Restaurant AKe wehpo yleosuo gmoein sgta artll tdoa yyo!ur day! SALADS Gado Gado Pasteur 45 Tom Yam Goong 48 Indonesian salad of slightly blanched vegetables and Thai favorite soup made of prawn stock blended with tom yam hard-boiled eggs, fried tofu and tempe, rice cake, served with secret recipes filled with mushroom, tomatoes and prawn a peanut sauce Sup Ala Thailand dengan campuran jamur, tomat dan udang Salad ala Indonesia berupa sayuran rebus disajikan dengan telur rebus, tahu dan tempe goreng, lontong serta saus Clear Vegetable Soup 35 kacang Combine of carrot, potato, green bean, broccoli and onion Sup bening sayuran dengan campuran wortel, kentang, buncis, Classic Caesar Salad 45 brokoli dan bawang bombay Fresh lettuce toast with caesar dressing combine with beef bacon, anchovy, parmesan cheese and crouton Salad ala Caesar dengan saus caesar, daging sapi asap, ikan SANDWICHES teri, keju parmesan dan roti kering Primera Club Sandwich 58 add Grilled Chicken 20 Three layer of toasted bread filled with smoked beef, chicken, dengan daging ayam panggang cheese, fried egg and served with fries Tiga lapis roti dengan lapisan daging sapi asap, daging ayam, add Smoked Salmon 40 keju, telur goreng dan disajikan dengan kentang goreng dengan ikan salmon asap American Mac Burger 98 Fruit salad with no added sugar 35 Burger buns filled with beef patties, lettuce, tomatoes, onion, Combination of mixed fruits with yoghurt dressing pickle, cheese and sunny side up egg served with fries -

BAB V KESIMPULAN DAN SARAN 5.1 Kesimpulan Berdasarkan Hasil

BAB V KESIMPULAN DAN SARAN 5.1 Kesimpulan Berdasarkan hasil penelitian yang diperoleh penulis dan telah dipaparkan pada bab sebelumnya mengenai pelestarian Gepuk sebagai warisan Gastronomi Jawa Barat. Kesimpulan tersebut sebagai berikut: 1. Gepuk menjadi salah satu makanan khas Sunda berperan sebagai variasi lauk pauk dalam memenuhi kebutuhan protein hewani masyarakat Sunda. Lalu menjadi sajian yang cocok dibawa saat berpergian. Gepuk dapat dikonsumsi kapanpun selama menginginkannya. Gepuk hanya sebagai makanan awetan saja. Tidak ada perlambangan khusus pada Gepuk. Selain itu, Gepuk menjadi makanan kelas menengah atas dan istimewa di lingkungan masyarakat Sunda. Tidak ada aturan khusus yang khas pada Gepuk. Selama orang yang akan mengkonsumsi memiliki gigi dan pengolahannya secara halal. Adapun kembali lagi kepada kemampuan daya beli seseorang. Lalu tidak ada tata cara dan penyajian khusus pada Gepuk. Semua kembali pada keoriginalitasan orang Sunda. Penggunaan peralatan makan pun yang ada tidak menjadi masalah. Gepuk pun biasa disajikan bersama nasi, sambal dan lalap sebagai pelengkapnya. Saat ini pun sayur asam telah menjadi menu pendamping yang cocok disajikan dengan Gepuk. Lalu adapun Gepuk khas Sunda berbeda dengan olahan yang sama di Jawa. Gepuk di Jawa lebih dikenal dengan nama Empal dengan tekstur dan rasa sesuai dengan ciri khas di daerahnya. 2. Gepuk merupakan sajian yang memiliki karakteristik khusus yaitu terbuat dari bagian paha belakang daging Sapi. Gula merah dan Gula sebagai bumbu yang digunakan. Lalu penggunaan lengkuas, ketumbar dan bawang putih menjadi rempah-rempah yang khas pada Gepuk. Bumbu dan rempah khas yang digunakan pada dasarnya mengandung bahan pengawet alami. Kemudian tidak ada peralatan khusus yang mesti digunakan pada saat proses pengolahannya. -

(IJLLT) Indonesian Dishes in the English Target Novel

International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation (IJLLT) ISSN: 2617-0299 (Online); ISSN: 2708-0099 (Print) DOI: 10.32996/ijllt Journal Homepage: www.al-kindipublisher.com/index.php/ijllt Indonesian Dishes in the English Target Novel Erlina Zulkifli Mahmud1*, Taufik Ampera2 , Inu Isnaeni Sidiq3 1Faculty of Cultural Sciences, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia 2Faculty of Cultural Sciences, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia 3Faculty of Cultural Sciences, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia Corresponding Author: Erlina Zulkifli Mahmud E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Received: November 08, 2020 This article discusses how Indonesian dishes in an Indonesian source novel are Accepted: December 18, 2020 translated into the English target novel. The ingredients of the dishes may be Volume: 3 universal as they can be found in any other dishes all over the world but the names Issue: 12 given to the dishes can be very unique. This uniqueness in Translation Studies may DOI: 10.32996/ijllt.2020.3.12.15 lead to a case of untranslatability as it has no direct equivalence or no one-to-one equivalence known as non-equivalence. For this non-equivalence case Baker KEYWORDS proposes 8 translation strategies under the name of translation strategy for non- equivalence at word level used by professional translators. What strategies are Indonesian dish, non-equivalence used in translating the Indonesian dishes based on Baker’s taxonomy and what at word level, semantic semantic components are involved in the English equivalences are the objectives of components, translation strategy this research. Using a mixed method; descriptive, contrastive, qualitative methods, the phenomena found in the source novel and in the target novel are compared, then documented into a description just the way they are, then analyzed to be identified according to the objectives of the research.