Chad: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No.: 20986 CD PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT Public Disclosure Authorized ONA PROPOSED CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 50.8 MILLION (US$67 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE REPUBLIC OF CHAD FOR THE Public Disclosure Authorized NATIONAL TRANSPORT PROGRAM SUPPORT PROJECT September 29, 2000 Public Disclosure Authorized TransportGroup (AFTTR) Centraland WesternAfrica Africa Region CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of August 17, 2000) Currency Unit = FCFA FCFA 720 = US$ 1.00 US$0.138 = 100 FCFA BORROWER'S FISCAL YEAR: January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AFD Agence Fran,aise de Developpement AfDB African Development Bank CAER Compte Autonome d'Entretien Routier CAS Country Assistance Strategy CISCP Cellule Intenninisterielle de Suivi et Coordination des Projets DR Direction des Routes DTS Direction des Transports de Surface DEP Direction des Etudes et de la Programmation EU European Union FED Fonds Europeen de Developpement FER Fonds d'Entretien Routier IMF International Monetary Fund IMT Intermediate Means of Transport MTPTHU Ministere des Travaux Publics, Transports, Habitat et Urbanisme NMT Non-Motorized Transport NPV Net Present Value PIEU Project Implementation Unit PPF Project Preparation Facility PST2 Second Transport Sector Project RTT Rural Travel and Transport RTTP Rural Travel and Transport Program SNER Societe Nationale d'Entretien Routier SSATP Sub- Saharan Africa Transport Policy Program VOC Vehicle Operating Costs Vice President: Callisto Madavo Country Director: Robert Calderisi Sector Manager: Maryvonne Plessis-Fraissard Task Team Leader: Andreas Schliessler Chad National Transport Program Support Project CONTENTS A Project Development Objective .................................................................. 2 1. Project development objective.................................................................. 2 2. Key performance indicators ................................................................. 2 B Strategic Context ................................................................. -

Summary of Protected Areas in Chad

CHAD Community Based Integrated Ecosystem Management Project Under PROADEL GEF Project Brief Africa Regional Office Public Disclosure Authorized AFTS4 Date: September 24, 2002 Team Leader: Noel Rene Chabeuf Sector Manager: Joseph Baah-Dwomoh Country Director: Ali Khadr Project ID: P066998 Lending Instrument: Adaptable Program Loan (APL) Sector(s): Other social services (60%), Sub- national government administration (20%), Central government administration (20%) Theme(s): Decentralization (P), Rural services Public Disclosure Authorized and infrastructure (P), Other human development (P), Participation and civic engagement (S), Poverty strategy, analysis and monitoring (S) Global Supplemental ID: P078138 Team Leader: Noel Rene Chabeuf Sector Manager/Director: Joseph Baah-Dwomoh Lending Instrument: Adaptable Program Loan (APL) Focal Area: M - Multi-focal area Supplement Fully Blended? No Sector(s): General agriculture, fishing and forestry sector (100%) Theme(s): Biodiversity (P) , Water resource Public Disclosure Authorized management (S), Other environment and natural resources management (S) Program Financing Data Estimated APL Indicative Financing Plan Implementation Period Borrower (Bank FY) IDA Others GEF Total Commitment Closing US$ m % US$ m US$ m Date Date APL 1 23.00 50.0 17.00 6.00 46.00 11/12/2003 10/31/2008 Government of Chad Loan/ Credit APL 2 20.00 40.0 30.00 0 50.00 07/15/2007 06/30/2012 Government of Chad Loan/ Credit Public Disclosure Authorized APL 3 20.00 33.3 40.00 0 60.00 03/15/2011 12/31/2015 Government of Chad Loan/ Credit Total 63.00 93.00 156.00 1 [ ] Loan [X] Credit [X] Grant [ ] Guarantee [ ] Other: APL2 and APL3 IDA amounts are indicative. -

IOM Nigeria DTM COVID-19 Point of Entry Dashboard (June 2020)

COVID-19 Point of Entry Dashboard: DTM North East Nigeria. Nigeria Monthly Snapshot June, 2020 Mamdi Barh-El-Gazel Ouest Wayi Mobbar Kukawa Lac Guzamala Dagana Dababa 45 766 Gubio Hadjer-Lamis Total movements (within, incoming and outgoing) Monguno Points of Entry Nganzai Ghana Haraze-Al-Biar observed Marte Magumeri Ngala N'Djamena 7 N'Djaména Yobe 164 Kala/Balge 13 OVERVIEW Jere Mafa Dikwa IOM DTM in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) and the state Ministry of Health Maiduguri 13 Chari Kaga Chad Baguirmi have been conducting monitoring of individuals moving into Nigeria's conflict-affected northeastern Konduga Bama Chari-Baguirmi Bauchi states of Adamawa and Borno under pillar four (Points of entry) of COVID 19 preparedness and Borno Pulka Immigration Poe response planning guidelines. Gwoza Nigeria Damboa 29 211 Mayo-Lemié Chibok During the period 1 to 30 June 2020, 766 movements were observed at Forty Five Points of Entries in Biu Madagali Loug-Chari Extreme-Nord Adamawa and Borno states. Of the total movements recorded, 211 were incoming from Extreme-Nord, Askira/Uba Michika Mubi Road Kwaya Kusar Uba 34 from Nord, 6 from Centre in Cameroon and 13 from N’Djamena in Chad republic. A total of 264 Bayo Hawul Gombe 35 Mubi North Mayo-Boneye Incoming movements were observed at Seventeen Points of Entries. Bauchi HongMunduva Bahuli Shani Gombi BurhaKwaja Mayo-Kebbi Est 6 Kolere 4 Cameroon Shelleng Mayo-Binder A range of data was collected during the assessment to better inform on migrants’ nationalities, gender, Guyuk Song Maiha Mont Illi Bauchi Tashan Belel reasons for moving, mode of transportation and timeline of movement as shown in Figures 1 to 4 below: Adamawa 1 Tandjilé Est Lac Léré Lamurde 1 Kabbia Numan Girei Bilaci Tandjile Ouest Demsa Yola South Garin Dadi Mayo-Kebbi Ouest Tandjilé Kwarwa 34 Tandjilé Centre MAIN NATIONALITIES OBSERVED (FIG. -

Working Paper 2017-06

worki! ownng pap er 2017-06 Universite Laval The impact of oil exploitation on wellbeing in Chad Gadom Djal Gadom Armand Mboutchouang Kountchou Gbetoton Nadège Adèle Djossou Gilles Quentin Kane Abdelkrim Araar February 2017 i The impact of oil exploitation on wellbeing in Chad Abstract This study assesses the impact of oil revenues on wellbeing in Chad using data from the two last Chad Household Consumption and Informal Sector Surveys (ECOSIT 2 & 3), conducted in 2003 and 2011, respectively, by the National Institute of Statistics for Economics and Demographic Studies (INSEED) and, from the College for Control and monitoring of Oil Revenues (CCSRP). To achieve the research objective, we first estimate a synthetic index of multidimensional wellbeing (MDW) based on a large set of welfare indicators. Then, the Difference-in-Difference (DID) approach is used to assess the impact of oil revenues on the average MDW at departmental level. We find evidence that departments receiving intense oil transfers increased their MDW about 35% more than those disadvantaged by the oil revenues redistribution policy. Moreover, the further a department is from the capital city N’Djamena, the lower its average MDW. We conclude that to better promote economic inclusion in Chad, the government should implement a specific policy to better direct the oil revenue investment in the poorest departments. Keys words: Poverty, Multidimensional wellbeing, Oil exploitation, Chad, Redistribution policy. JEL Codes: I32, D63, O13, O15 Authors Gadom Djal Gadom Mboutchouang -

Myr 2010 Chad.Pdf

ORGANIZATIONS PARTICIPATING IN CONSOLIDATED APPEAL CHAD ACF CSSI IRD UNDP ACTED EIRENE Islamic Relief Worldwide UNDSS ADRA FAO JRS UNESCO Africare Feed the Children The Johanniter UNFPA AIRSERV FEWSNET LWF/ACT UNHCR APLFT FTP Mercy Corps UNICEF Architectes de l’Urgence GOAL NRC URD ASF GTZ/PRODABO OCHA WFP AVSI Handicap International OHCHR WHO BASE HELP OXFAM World Concern Development Organization CARE HIAS OXFAM Intermon World Concern International CARITAS/SECADEV IMC Première Urgence World Vision International CCO IMMAP Save the Children Observers: CONCERN Worldwide INTERNEWS Sauver les Enfants de la Rue International Committee of COOPI INTERSOS the Red Cross (ICRC) Solidarités CORD IOM Médecins Sans Frontières UNAIDS CRS IRC (MSF) – CH, F, NL, Lux TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................................. 1 Table I: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by cluster) ................................................... 3 Table II: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by appealing organization).......................... 4 Table III: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by priority)................................................... 5 2. CHANGES IN THE CONTEXT, HUMANITARIAN NEEDS AND RESPONSE ........................................... 6 3. PROGRESS TOWARDS ACHIEVING STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES AND SECTORAL TARGETS .......... 9 3.1 STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................................ -

CAR CMP Population Moveme

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SITUATION Election-related displacements in CAR Cluster Protec�on République Centrafricaine As of 30 April 2021 Chari Dababa Guéra KEY FIGURES Refugee camp Number of CAR IDPs Mukjar As Salam - SD Logone-et-Chari Abtouyour Aboudéia !? Entry point Baguirmi newly displaced Kimi� Mayo-Sava Tulus Gereida Interna�onal boundaries Number of CAR returns Rehaid Albirdi Mayo-Lemié Abu Jabrah 11,148 15,728 Administra�ve boundaries level 2 Barh-Signaka Bahr-Azoum Diamaré SUDAN Total number of IDPs Total number of Um Dafoug due to electoral crisis IDPs returned during Mayo-Danay during April April Mayo-Kani CHAD Mayo-Boneye Birao Bahr-Köh Mayo-Binder Mont Illi Moyo Al Radoum Lac Léré Kabbia Tandjile Est Lac Iro Tandjile Ouest Total number of IDPs ! Aweil North 175,529 displaced due to crisis Mayo-Dallah Mandoul Oriental Ouanda-Djalle Aweil West La Pendé Lac Wey Dodjé La Nya Raja Belom Ndele Mayo-Rey Barh-Sara Aweil Centre NEWLY DISPLACED PERSONS BY ZONE Gondje ?! Kouh Ouest Monts de Lam 3,727 8,087 Ouadda SOUTH SUDAN Sous- Dosseye 1,914 Kabo Bamingui Prefecture # IDPs CAMEROON ?! ! Markounda ! prefecture ?! Batangafo 5,168!31 Kaga-Bandoro ! 168 Yalinga Ouham Kabo 8,087 Ngaoundaye Nangha ! ! Wau Vina ?! ! Ouham Markounda 1,914 Paoua Boguila 229 Bocaranga Nana Mbres Ouham-Pendé Koui 406 Borgop Koui ?! Bakassa Bria Djema TOuham-Pendéotal Bocaranga 366 !406 !366 Bossangoa Bakala Ippy ! Mbéré Bozoum Bouca Others* Others* 375 ?! 281 Bouar Mala Total 11,148 Ngam Baboua Dekoa Tambura ?! ! Bossemtele 2,154 Bambari Gado 273 Sibut Grimari -

2.3 Chad Road Network

2.3 Chad Road Network National Road Network Rural network Distance Matrix Time Travel Matrix Road Security Weighbridges Axle Load Limits Bridges Road Class Statistics of the existing roads in Chad Surface Conditions Rain Barriers Ouadis (drifts) Page 1 Page 2 For information on Chad Road Network contact details, please see the following link: 4.1 Chad Government Contact List Located in Central Africa at an average altitude of 200 meters, Chad is a large Sahelian country stretching over 2,000 km from north to south and 1,000 km from east to west, covering an area of 1,284 .000 km². Totally landlocked, it shares 5,676 km of borders with 6 bordering countries, including: • 1,055 km to the north with Libya along an almost straight line • 1,360 km to the east with Sudan. • 1,197 km to the south with the Central African Republic. • 889 km to the southwest with Nigeria (89 km of common territorial waterscon Lake Chad) and Cameroon (800 km). • 1,175 km to the west with Niger Chad's road network, both paved and unpaved, is very poorly rarely maintained. According to official road authorities 6000 km of asphalted roads are planned of which a total of 2,086 km are paved and open to the traffic at end of 2014. A 380-km construction project is underway. 4 large asphalting projects planned since 2010 are ongoing and constructions are realized by one Chinese enterprise and Arab Contractor an Egyptian enterprise. Moundou Doba – Koumra (190 km); Massaget – Massakory (72 km) Bokoro – Arboutchatak (65 km); Abeche – Am Himede – Oul Hadjer – Mongo. -

Wt/Tpr/S/285 • Chad

WT/TPR/S/285 • CHAD - 369 - ANNEX 5 CHAD WT/TPR/S/285 • CHAD - 370 - CONTENTS 1 ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT ...................................................................................... 373 1.1 Main features ......................................................................................................... 373 1.2 Recent economic developments ................................................................................ 375 1.3 Trends in trade and investment ................................................................................ 376 1.4 Outlook ................................................................................................................. 379 2 TRADE AND INVESTMENT REGIMES ......................................................................... 380 2.1 Overview ............................................................................................................... 380 2.2 Trade policy objectives ............................................................................................ 383 2.3 Trade agreements and arrangements ........................................................................ 383 2.3.1 World Trade Organization ...................................................................................... 383 2.3.2 Relations with the European Union ......................................................................... 384 2.3.3 Relations with the United States ............................................................................ 384 2.3.4 Other agreements ............................................................................................... -

IOM Nigeria DTM COVID-19 Point of Entry Dashboard 16

COVID-19 Point of Entry Dashboard 16: DTM North East Nigeria. Nigeria 22 - 28 AUGUST 2020 Barh-El-Gazel Nord KEY FIGURES Fouli Kanem Kanem Barh-El-Gazel Sud Kaya Barh-El-Gazel Wadi Bissam Abadam Lac 47 Barh-El-Gazel Ouest 9 Wayi Total movements (within, incoming and outgoing) Mamdi Points of Entry observed Mobbar Kukawa Dagana OVERVIEW Guzamala Hadjer-Lamis IOM DTM in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Gubio Monguno Nganzai Haraze-Al-Biar state Ministry of Health have been conducting monitoring of individuals moving Marte Ghana Dababa into Nigeria's conflict-affected northeastern states of Adamawa and Borno Gamboru B Yobe Magumeri Ngala N'Djamena under pillar four (Points of entry) of COVID 19 preparedness and response N'Djaména Kala/Balge BornoJere Mafa 11 10 planning guidelines. Dikwa Maiduguri Chari Kaga During the period 22 - 28 August 2020, 47 movements were observed at Nine Konduga Baguirmi Bama Chari-Baguirmi Points of Entries in Adamawa and Borno states. Of the total movements recorded, 10 were incoming from N’djamena in Chad and 1 from Extreme Nord Bauchi Gwoza in Cameroon. Damboa Chad 1 Mayo-Lemié Chibok Madagali Biu Extreme-Nord A range of data was collected during the assessment to better inform on Nigeria Opp Michika Secretary Askira/Uba migrants’ nationalities, gender, reasons for moving, mode of transportation and Michika Loug-Chari Kwaya Kusar Hawul timeline of movement as shown in Figures 1 to 4 below: Bayo Nzakwa Gombe Adamawa Mubi North . Bauchi Hong Mayo-Boneye Shani Gombi Mubi SouthDuvu Mayo-Kebbi Est MAIN NATIONALITIES OBSERVED (FIG. -

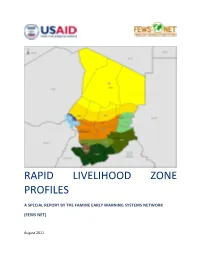

Rapid Livelihood Zone Profiles for Chad

RAPID LIVELIHOOD ZONE PROFILES A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Contents Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 The Uses of the Profiles ............................................................................................................................ 4 Key Concepts ............................................................................................................................................. 5 What is in a Livelihood Profile .................................................................................................................. 7 Methodology ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Rapid Livelihood Zone Profiles for Chad ....................................................................................................... 9 National Overview .................................................................................................................................... 9 Zone 1: South cereals and cash crops ..................................................................................................... 13 Zone 2: Southwest Rice Dominant ......................................................................................................... -

French) (Arabic

Coor din ates: 1 5 °N 1 9 °E Chad Tashād; French: Tchad ﺗﺸﺎد :Chad (/tʃæd/ ( listen); Arabic Republic of Chad pronou nced [tʃad]), officially the Republic of Chad (Jumhūrīyat Tshād; French: République République du Tchad (French ﺟﻤﮭﻮرﯾﺔ ﺗﺸﺎد :Arabic) (Arabic) ﺟﻣﮫورﻳﺔ ﺗﺷﺎد du Tchad lit. "Republic of the Chad"), is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to the Jumhūrīyat Tashād north, Sudan to the east, the Central African Republic to the south, Cameroon and Nigeria to the southwest, and Niger to the west. It is the fifth largest country in Africa and the second-largest in Central Africa in terms of area. Coat of arms Chad has several regions: a desert zone in the north, an arid Flag Sahelian belt in the centre and a more fertile Sudanian Motto: Savanna zone in the south. Lake Chad, after which the "Unité, Travail, Progrès" (French) country is named, is the largest wetland in Chad and the "Unity, Work, Progress" (Arabic) "اﻻﺗﺣﺎد، اﻟﻌﻣل، اﻟﺗﻘدم" second-largest in Africa. The capital N'Djamena is the largest city. Chad's official languages are Arabic and French. Anthem: Chad is home to over 200 different ethnic and linguistic La Tchadienne (French) groups. The most popular religion of Chad is Islam (at 55%), (Arabic) ﻧﺷﻳد ﺗﺷﺎد اﻟوطﻧﻲ followed by Christianity (at 40%). The Chadian Hymn Beginning in the 7 th millennium BC, human populations moved into the Chadian basin in great numbers. By the end of the 1st millennium AD, a series of states and empires had risen and fallen in Chad's Sahelian strip, each focused on controlling the trans-Saharan trade routes that passed through the region. -

IOM Nigeria DTM COVID-19 Point of Entry Dashboard

COVID-19 Point of Entry Dashboard: DTM North East Nigeria. Nigeria 25 - 31 JULY 2020 Barh-El-Gazel Nord KEY FIGURES Fouli Kanem Kanem Barh-El-Gazel Sud Kaya Barh-El-Gazel Wadi Bissam Abadam Lac Barh-El-Gazel Ouest 14 171 Wayi Total movements (within, incoming and outgoing) Mamdi Points of Entry observed Mobbar Kukawa Dagana OVERVIEW Guzamala IOM DTM in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Gubio Hadjer-Lamis Monguno Nganzai Gamboru 'B' Haraze-Al-Biar state Ministry of Health have been conducting monitoring of individuals moving Marte Ghana Dababa into Nigeria's conflict-affected northeastern states of Adamawa and Borno Borno Yobe Magumeri Ngala N'Djamena under pillar four (Points of entry) of COVID 19 preparedness and response N'Djaména 73 Kala/Balge Jere Mafa 4 planning guidelines. Dikwa Maiduguri 3 Chari Kaga During the period 25 - 31 July 2020, 171 movements were observed at Konduga Baguirmi Bama Chari-Baguirmi Fourteen Points of Entries in Adamawa and Borno states. Of the total Nigeria Pulka Immigration Poe Bauchi Chad movements recorded, 76 were incoming from Extreme-Nord, 8 from Nord in Gwoza Damboa Cameroon and 4 incoming from N’djamena in Chad Republic. 2 76 Mayo-Lemié Chibok Biu Madagali A range of data was collected during the assessment to better inform on Extreme-Nord Askira/Uba migrants’ nationalities, gender, reasons for moving, mode of transportation and Michika Loug-Chari Kwaya Kusar 6 Bayo Hawul timeline of movement as shown in Figures 1 to 4 below: Gombe Hong Mubi North Bauchi Mubi South Mayo-Boneye .