Download Full Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

X001132127.Pdf

' ' ., ,�- NONIMPORTATION AND THE SEARCH FOR ECONOMIC INDEPENDENCE IN VIRGINIA, 1765-1775 BRUCE ALLAN RAGSDALE Charlottesville, Virginia B.A., University of Virginia, 1974 M.A., University of Virginia, 1980 A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Corcoran Department of History University of Virginia May 1985 © Copyright by Bruce Allan Ragsdale All Rights Reserved May 1985 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: 1 Chapter 1: Trade and Economic Development in Virginia, 1730-1775 13 Chapter 2: The Dilemma of the Great Planters 55 Chapter 3: An Imperial Crisis and the Origins of Commercial Resistance in Virginia 84 Chapter 4: The Nonimportation Association of 1769 and 1770 117 Chapter 5: The Slave Trade and Economic Reform 180 Chapter 6: Commercial Development and the Credit Crisis of 1772 218 Chapter 7: The Revival Of Commercial Resistance 275 Chapter 8: The Continental Association in Virginia 340 Bibliography: 397 Key to Abbreviations used in Endnotes WMQ William and Mary Quarterly VMHB Virginia Magazine of History and Biography Hening William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large; Being� Collection of all the Laws Qf Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature in the year 1619, 13 vols. Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia Rev. Va. Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, 7 vols. LC Library of Congress PRO Public Record Office, London co Colonial Office UVA Manuscripts Department, Alderman Library, University of Virginia VHS Virginia Historical Society VSL Virginia State Library Introduction Three times in the decade before the Revolution. Vir ginians organized nonimportation associations as a protest against specific legislation from the British Parliament. -

International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding (IJMMU) Vol

Comparative Study of Post-Marriage Nationality Of Women in Legal Systems of Different Countries http://ijmmu.com [email protected] International Journal of Multicultural ISSN 2364-5369 Volume 2, Issue 6 and Multireligious Understanding December, 2015 Pages: 41-57 Public Perception on Calligraphic Woodcarving Ornamentations of Mosques; a Comparison between East Coast and Southwest of Peninsula Malaysia Ahmadreza Saberi1; Esmawee Hj Endut1; Sabarinah Sh Ahmad1; Shervin Motamedi2,3; Shahab Kariminia4; Roslan Hashim2,3 1 Faculty of Architecture, Planning and Surveying, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Shah Alam, 40450, Malaysia Email: [email protected] 2 Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University of Malaya, 50603, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 3 Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences (IOES), University of Malaya, 50603, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 4 Department of Architecture, Faculty of Art, Architecture and Urban Planning, Najafabad Branch, Islamic Azad University, Najafabad, Isfahan, Iran Abstract Woodcarving ornamentation is considered as, a national heritage and can be found in many Malaysian mosques. Woodcarvings are mostly displayed in three different motifs, namely floral, geometry and calligraphy. The application of floral and geometry motifs is to convey an abstract meaning of Islamic teachings to the viewers. However, the calligraphic decorations directly express the messages of Allah almighty or the sayings of the prophets to the congregations. Muslims are the main users of mosques as these are places for prayers as well as other religious and community activities. Therefore, the assessment of users’ opinion about this type of decoration needs to be investigated. This paper aims to evaluate the perception of two groups of mosque users on the calligraphic woodcarving ornamentations from two regions, namely the East Coast and Southwest of Peninsula Malaysia. -

The Macroeconomic Effects of Banking Crises Evidence from the United Kingdom, 1750-1938 Kenny, Seán; Lennard, Jason; Turner, John D

The Macroeconomic Effects of Banking Crises Evidence from the United Kingdom, 1750-1938 Kenny, Seán; Lennard, Jason; Turner, John D. 2017 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kenny, S., Lennard, J., & Turner, J. D. (2017). The Macroeconomic Effects of Banking Crises: Evidence from the United Kingdom, 1750-1938. (Lund Papers in Economic History: General Issues; No. 165). Department of Economic History, Lund University. Total number of authors: 3 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Lund Papers in Economic History No. 165, 2017 General Issues The Macroeconomic Effects of Banking Crises: Evidence from the United Kingdom, 1750-1938 Seán Kenny, Jason Lennard & John D. -

Friday, May 8, 2009

Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology Rose-Hulman Scholar The Rose Thorn Archive Student Newspaper Spring 5-8-2009 Volume 44 - Issue 25 - Friday, May 8, 2009 Rose Thorn Staff Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn Recommended Citation Rose Thorn Staff, "Volume 44 - Issue 25 - Friday, May 8, 2009" (2009). The Rose Thorn Archive. 154. https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn/154 THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS ROSE-HULMAN REPOSITORY IS TO BE USED FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP, OR RESEARCH AND MAY NOT BE USED FOR ANY OTHER PURPOSE. SOME CONTENT IN THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT. ANYONE HAVING ACCESS TO THE MATERIAL SHOULD NOT REPRODUCE OR DISTRIBUTE BY ANY MEANS COPIES OF ANY OF THE MATERIAL OR USE THE MATERIAL FOR DIRECT OR INDIRECT COMMERCIAL ADVANTAGE WITHOUT DETERMINING THAT SUCH ACT OR ACTS WILL NOT INFRINGE THE COPYRIGHT RIGHTS OF ANY PERSON OR ENTITY. ANY REPRODUCTION OR DISTRIBUTION OF ANY MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY IS AT THE SOLE RISK OF THE PARTY THAT DOES SO. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspaper at Rose-Hulman Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rose Thorn Archive by an authorized administrator of Rose-Hulman Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. T HE R OSE T HORN R OSE -H ULMAN I NSTITUTE OF T ECHNOLOGY T ERRE H AUTE , I NDIANA FRIDAY, MAY 8, 2009 ROSE-HULMAN.EDU/THORN/ VOLUME 43, ISSUE 25 Greek Games a success News Briefs Lindsey Saxton from campus safety and fa- By Andy Klusman Advertising cilities-- shutting down the M a n a g e r roads and providing tables.” Barron also said, “This year, Dom DeLuise n May 3rd, over 250 we wanted to entice more Rose students gath- people to come out and par- dead at 75 Oered to uphold an ticipate, so we made t-shirts Actor Dom DeLuise died Monday night honored Greek tradition, the to help advertise, and these in a Los Angeles hospital. -

Tsr6903.Mu7.Ghotmu.C

[ Official Game Accessory Gamer's Handbook of the Volume 7 Contents Arcanna ................................3 Puck .............. ....................69 Cable ........... .... ....................5 Quantum ...............................71 Calypso .................................7 Rage ..................................73 Crimson and the Raven . ..................9 Red Wolf ...............................75 Crossbones ............................ 11 Rintrah .............. ..................77 Dane, Lorna ............. ...............13 Sefton, Amanda .........................79 Doctor Spectrum ........................15 Sersi ..................................81 Force ................................. 17 Set ................. ...................83 Gambit ................................21 Shadowmasters .... ... ..................85 Ghost Rider ............................23 Sif .................. ..................87 Great Lakes Avengers ....... .............25 Skinhead ...............................89 Guardians of the Galaxy . .................27 Solo ...................................91 Hodge, Cameron ........................33 Spider-Slayers .......... ................93 Kaluu ....... ............. ..............35 Stellaris ................................99 Kid Nova ................... ............37 Stygorr ...............................10 1 Knight and Fogg .........................39 Styx and Stone .........................10 3 Madame Web ...........................41 Sundragon ................... .........10 5 Marvel Boy .............................43 -

Talus Corrina Carter Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2016 Talus Corrina Carter Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Carter, Corrina, "Talus" (2016). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 16509. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/16509 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Talus by Corrina Carter A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Major: Creative Writing and Environment Program of Study Committee: K. L. Cook, Major Professor Charissa Menefee Catherine M. McMullen Matthew Sivils Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2016 Copyright © Corrina Carter, 2016. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE................................................................................................................... iii BOOK 1 ……………………………………………………………………………. 1 BOOK II ……………………………………………………………………………. 150 BOOK III …………………………………………………………………………… 228 BOOK IV …………………………………………………………………………… 331 iii PREFACE When, after considering several more literary projects for my thesis, I committed to writing Talus, I realized a grueling research project awaited me. In order to write a successful “talking animal” novel for a young adult audience, I had to revisit the classics of anthropomorphic fiction (my favorite genre as a child), study equine behavior, deepen my knowledge of the mustang controversy, a hot topic in the American West, and learn the natural history of Oregon’s dry side, where my book takes place. -

CALIFORNIA's NORTH COAST: a Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors

CALIFORNIA'S NORTH COAST: A Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors. A Geographically Arranged Bibliography focused on the Regional Small Presses and Local Authors of the North Coast of California. First Edition, 2010. John Sherlock Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian University of California, Davis. 1 Table of Contents I. NORTH COAST PRESSES. pp. 3 - 90 DEL NORTE COUNTY. CITIES: Crescent City. HUMBOLDT COUNTY. CITIES: Arcata, Bayside, Blue Lake, Carlotta, Cutten, Eureka, Fortuna, Garberville Hoopa, Hydesville, Korbel, McKinleyville, Miranda, Myers Flat., Orick, Petrolia, Redway, Trinidad, Whitethorn. TRINITY COUNTY CITIES: Junction City, Weaverville LAKE COUNTY CITIES: Clearlake, Clearlake Park, Cobb, Kelseyville, Lakeport, Lower Lake, Middleton, Upper Lake, Wilbur Springs MENDOCINO COUNTY CITIES: Albion, Boonville, Calpella, Caspar, Comptche, Covelo, Elk, Fort Bragg, Gualala, Little River, Mendocino, Navarro, Philo, Point Arena, Talmage, Ukiah, Westport, Willits SONOMA COUNTY. CITIES: Bodega Bay, Boyes Hot Springs, Cazadero, Cloverdale, Cotati, Forestville Geyserville, Glen Ellen, Graton, Guerneville, Healdsburg, Kenwood, Korbel, Monte Rio, Penngrove, Petaluma, Rohnert Part, Santa Rosa, Sebastopol, Sonoma Vineburg NAPA COUNTY CITIES: Angwin, Calistoga, Deer Park, Rutherford, St. Helena, Yountville MARIN COUNTY. CITIES: Belvedere, Bolinas, Corte Madera, Fairfax, Greenbrae, Inverness, Kentfield, Larkspur, Marin City, Mill Valley, Novato, Point Reyes, Point Reyes Station, Ross, San Anselmo, San Geronimo, San Quentin, San Rafael, Sausalito, Stinson Beach, Tiburon, Tomales, Woodacre II. NORTH COAST AUTHORS. pp. 91 - 120 -- Alphabetically Arranged 2 I. NORTH COAST PRESSES DEL NORTE COUNTY. CRESCENT CITY. ARTS-IN-CORRECTIONS PROGRAM (Crescent City). The Brief Pelican: Anthology of Prison Writing, 1993. 1992 Pelikanesis: Creative Writing Anthology, 1994. 1994 Virtual Pelican: anthology of writing by inmates from Pelican Bay State Prison. -

Regency Actors and the Inspiration Behind Romantic Drama

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2017 Fit for the Stage: Regency Actors and the Inspiration Behind Romantic Drama James Armstrong The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2317 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] FIT FOR THE STAGE: REGENCY ACTORS AND THE INSPIRATION BEHIND ROMANTIC DRAMA by JAMES ARMSTRONG A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 ii © 2017 JAMES ARMSTRONG All Rights Reserved iii Fit for the Stage: Regency Actors and the Inspiration Behind Romantic Drama by James Armstrong This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. May 12, 2017 ______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Marvin Carlson Distinguished Professor May 12, 2017 ______________________________ Date Executive Officer Peter Eckersall Professor ______________________________ Jean Graham-Jones Professor ______________________________ Annette J. Saddik Professor Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract Fit for the Stage: Regency Actors and the Inspiration Behind Romantic Drama by James Armstrong Adviser: Distinguished Professor Marvin Carlson In this dissertation, I argue that British verse tragedies of the Romantic era must be looked at not as "closet dramas" divorced from the stage, but as performance texts written with specific actors in mind. -

The Diaries of Elizabeth Inchbald

www.pickeringchatto.com/inch b a l d The Diaries of Elizabeth Inchbald Editor: Ben P Robertson The Pickering Masters 3 Volume Set: c.1200pp: September 2007 978 1 85196 868 8: £275/$495 he diaries of Elizabeth Inchbald T(1753–1821) are rare and fragile documents which present a unique view of Romantic-era Britain. An energetic woman, Inchbald achieved fame as an actress, novelist, playwright and critic. Her career introduced her to a wide group of people and she counted William Godwin, Thomas Holcro�, Maria Edgeworth, Sarah Siddons and John Philip Kemble among her friends. Published here for the first time, her eleven surviving diaries are a fascinating vigne�e of everyday life in the theatrical and literary circles of eighteenth-century London. They record Inchbald’s reading habits, social contacts and professional activities, Elizabeth Inchbald, from Simple Histoire (c.1795) itemize her day-to-day expenditure, Photograph courtesy of Chawton House Library and chart the development of current • New transcriptions from documents held at the affairs such as the Napoleonic Wars and the trial of Folger Shakespeare Library, Queen Caroline. Washington DC The diaries are fully transcribed, but a sense of the • A sense of the original manuscript is preserved original documents is preserved through selected through selected photographic reproductions and photographic reproductions, and descriptions of descriptions of the notebooks the physical notebooks. The editorial apparatus also contextualises the diaries and provides • Full editorial apparatus includes a substantial biographical details for Inchbald and the other general introduction, a chronology of figures she encountered. Inchbald’s life, brief introductions to each diary, bibliographical guides to figures mentioned, and The edition will appeal to scholars specializing textual notes in Eighteenth-Century Studies, Romantic Studies, Women’s Writing and Theatrical History. -

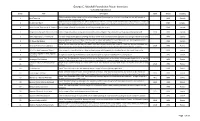

GCMF Poster Inventory

George C. Marshall Foundation Poster Inventory Compiled August 2011 ID No. Title Description Date Period Country A black and white image except for the yellow background. A standing man in a suit is reaching into his right pocket to 1 Back Them Up WWI Canada contribute to the Canadian war effort. A black and white image except for yellow background. There is a smiling soldier in the foreground pointing horizontally to 4 It's Men We Want WWI Canada the right. In the background there is a column of soldiers march in the direction indicated by the foreground soldier's arm. 6 Souscrivez à L'Emprunt de la "Victoire" A color image of a wide-eyed soldier in uniform pointing at the viewer. WWI Canada 2 Bring Him Home with the Victory Loan A color image of a soldier sitting with his gun in his arms and gear. The ocean and two ships are in the background. 1918 WWI Canada 3 Votre Argent plus 5 1/2 d'interet This color image shows gold coins falling into open hands from a Canadian bond against a blue background and red frame. WWI Canada A young blonde girl with a red bow in her hair with a concerned look on her face. Next to her are building blocks which 5 Oh Please Do! Daddy WWI Canada spell out "Buy me a Victory Bond" . There is a gray background against the color image. Poster Text: In memory of the Belgian soldiers who died for their country-The Union of France for Belgium and Allied and 7 Union de France Pour La Belqiue 1916 WWI France Friendly Countries- in the Church of St. -

Hungry Bengal: War, Famine, Riots, and the End of Empire 1939-1946

Hungry Bengal: War, Famine, Riots, and the End of Empire 1939-1946 By Janam Mukherjee A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) In the University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Barbara D. Metcalf, Chair Emeritus Professor David W. Cohen Associate Professor Stuart Kirsch Associate Professor Christi Merrill 1 "Unknown to me the wounds of the famine of 1943, the barbarities of war, the horror of the communal riots of 1946 were impinging on my style and engraving themselves on it, till there came a time when whatever I did, whether it was chiseling a piece of wood, or burning metal with acid to create a gaping hole, or cutting and tearing with no premeditated design, it would throw up innumerable wounds, bodying forth a single theme - the figures of the deprived, the destitute and the abandoned converging on us from all directions. The first chalk marks of famine that had passed from the fingers to engrave themselves on the heart persist indelibly." 2 Somnath Hore 1 Somnath Hore. "The Holocaust." Sculpture. Indian Writing, October 3, 2006. Web (http://indianwriting.blogsome.com/2006/10/03/somnath-hore/) accessed 04/19/2011. 2 Quoted in N. Sarkar, p. 32 © Janam S. Mukherjee 2011 To my father ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank first and foremost my father, Dr. Kalinath Mukherjee, without whom this work would not have been written. This project began, in fact, as a collaborative effort, which is how it also comes to conclusion. His always gentle, thoughtful and brilliant spirit has been guiding this work since his death in May of 2002 - and this is still our work. -

You May View It Or Download a .Pdf Here

“I put my trust in God” (“Tawakkaltu ‘ala ’illah”) Word 2012 —Arabic calligraphy in nasta’liq script on an ivy leaf 42976araD1R1.indd 1 11/1/11 11:37 PM Geometry of the Spirit WRITTEN BY DAVID JAMES alligraphy is without doubt the most original con- As well, there were regional varieties. From Kufic, Islamic few are the buildings that lack Hijazi tribution of Islam to the visual arts. For Muslim cal- Spain and North Africa developed andalusi and maghribi, calligraphy as ornament. Usu- Cligraphers, the act of writing—particularly the act of respectively. Iran and Ottoman Turkey both produced varie- ally these inscriptions were writing the Qur’an—is primarily a religious experience. Most ties of scripts, and these gained acceptance far beyond their first written on paper and then western non-Muslims, on the other hand, appreciate the line, places of origin. Perhaps the most important was nasta‘liq, transferred to ceramic tiles for Kufic form, flow and shape of the Arabic words. Many recognize which was developed in 15th-century Iran and reached a firing and glazing, or they were that what they see is more than a display of skill: Calligraphy zenith of perfection in the 16th century. Unlike all earlier copied onto stone and carved is a geometry of the spirit. hands, nasta‘liq was devised to write Persian, not Arabic. by masons. In Turkey and Per- The sacred nature of the Qur’an as the revealed word of In the 19th century, during the Qajar Dynasty, Iranian sia they were often signed by Maghribıi God gave initial impetus to the great creative outburst of cal- calligraphers developed from nasta‘liq the highly ornamental the master, but in most other ligraphy that began at the start of the Islamic era in the sev- shikastah, in which the script became incredibly complex, con- places we rarely know who enth century CE and has continued to the present.