Talus Corrina Carter Iowa State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Society Sage Pleases Greatly

~ » tell him about vp y V Then Ayer s Cherry I->ec- foral. Tell him how it cured your hard I_/ d n TEN DEAD IN HARPER HAS ^ MCllllr. A Cm if cough. Tell him why you always keep RECORD IS it on hand. Tell him to ask his doctor « it. Doctors use it a , a*> about great deal for /*§ 9* » /> /~C J all forms of throat and lung troubles. We HOTEL FIRE. PASSED AWAY LX A. S i fllj [ We have no secrelsI publish c AyerOo., DELIGHTED. Fire Gave President of Extends Olive Toward Gov- ^Minneapolis Captain Chicago University Twig | 8, 18. 20, 22, 24, 26 and 3o West Fourteenth Street. I to Save Woman- t, 9, ii. Vi. 15. 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23. 24, 25. 27 and 29 West Thirteenth Street, j Claimed Death-Cancer ernor-Tax Attitude in Mes- New York. ^ by _ MRS. MORRIS ___ , "Guests Jump. the Cause. Society sage Pleases Greatly. NEW YORK WEDDING. CNEAPOLIS, Minn., Jnn. 11.— CHICAHO, Jan. II.—William Rainey Corporation Counsel George L A number of people from this city i'est hotel, one of the largest anil of the of IS VERY ILL Record of Jersey City, who has been Sale Harper, president University will attend the marriage ceremony of January liostelrles in has In the front of the fight for equal the country, Chicago, dead at his home here after Miss Gussie Levy, daughter of Mr. here. Ten taxation, is elated over the attitude fcstroyed liy tire per- a long illness of cancer of the intes- and Mrs. -

Contemporary Issues in Gerontology: Promoting Positive Ageing

gerentology-TEXT PAGES 2/6/05 10:41 AM Page i Contemporary Issues in Gerontology Promoting Positive Ageing V. MINICHIELLO AND I. COULSON EDITORS gerentology-TEXT PAGES 2/6/05 10:41 AM Page ii First published in 2005 Copyright © Victor Minichiello and Irene Coulson 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. Allen & Unwin 83 Alexander Street Crows Nest NSW 2065 Australia Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100 Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 Email: [email protected] Web: www.allenandunwin.com National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Minichiello, Victor. Contemporary issues in gerontology: promoting positive ageing. Bibliography. Includes index. ISBN 1 86508 876 5. Gerontology - Australia. 2. Older people - Health and hygiene - Australia. 3. Older people - Care - Australia. 4. Older people - Services for - Australia. I. Coulson, Irene. II. Title. 305.260994 Set in 10/12 Hiroshige by Midland Typesetters, Maryborough, Victoria Printed by 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 gerentology-TEXT PAGES 2/6/05 10:41 AM Page iii Foreword Human ageing is a global phenomenon, linking north, south, east and west. -

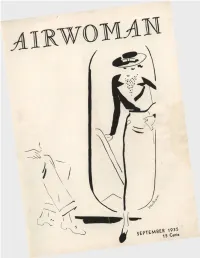

S E P T E M B E

SEPTEMBER” DINING BECOMES A FINE ART IN THE RENAISSANCE ROOM ^^uncheon's a gay event . dinner is a memorable masterpiece in this distinguished dining-salon at the Gotham. Delicious cuisine temptingly prepared, an impeccable service, charming atmosphere and congenial companionship all con tribute the necessary harmonies to an ensemble that is unex celled. The beautiful Renaissance Room offers a perfect setting for leisurely dining. Spacious, oak-paneled, with rich carvings and deep carpets, the light enters through the vaulted windows with mellow softness. Gayety sparkles in these magic surround ings. That's one of the reasons why people really "live" at the Gotham. Of course the hotel is also famous for its gracious hospitality, large tastefully furnished rooms and its excellent location, convenient to all parts of the city. See how much real comfort awaits you here at a surprisingly moderate rental. Rates from $4.00. Max A. Haering, Resilient Manager FIFTH AVENUE AT FIFTY-FIFTH STREET • NEW YORK CITY Official Headquarters of the 99 Club and Women's National Aeronautical Association FOUR REASONS f o r ^ I R W O T W N ORDERING YOUR FURS NOW * in August you have the pick of the winter pelts . * Leisurely selection . * Savings in workmanship (because up to September 1st work is done CONTENTS at special summer prices) . Laura Ingalls' Record Ship 4 * PELT PRICES HAVE ADVANCED SINCE Scoring Up............................................................ 5 OUR PRESENT STOCK WAS ASSEMBLED Dizzy Depths to Dizzy Heights— By Jeanette AND IT IS UNLIKELY THEY W ILL BE SO LOW AGAIN THIS SEASON . Lempke ........................................... Fay Gillis Invades Ethiopia OUR WINTER MODELS are now being shown Fall Fashion Flashes in the Custom Fur Shop: and The Little Shop of Ready Just Among Us Girls— By Mister Swanee Taylor 8 Furs has reopened with an exceptional collection. -

Dorothy West (Actress) Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

Dorothy West (actress) 电影 串行 (大全) A Strange Meeting https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-strange-meeting-2561940/actors The Roue's Heart https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-roue%27s-heart-3522553/actors The Spanish https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-spanish-gypsy-3989411/actors Gypsy The Thread of https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-thread-of-destiny-3989628/actors Destiny Examination Day https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/examination-day-at-school-3735884/actors at School The Newlyweds https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-newlyweds-3988491/actors The Oath and the https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-oath-and-the-man-3988525/actors Man The Chief's https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-chief%27s-daughter-3520255/actors Daughter I Did It https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/i-did-it-3147065/actors A Romance of the https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-romance-of-the-western-hills-3602709/actors Western Hills A Plain Song https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-plain-song-3602667/actors The Light That https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-light-that-came-3988006/actors Came The Impalement https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-impalement-3987666/actors A Victim of https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-victim-of-jealousy-3602821/actors Jealousy The Death Disc: A Story of the https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-death-disc%3A-a-story-of-the-cromwellian-period-3986553/actors Cromwellian Period His Trust https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/his-trust-3785833/actors -

![Jambalaya [Yearbook] 1900](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7545/jambalaya-yearbook-1900-2707545.webp)

Jambalaya [Yearbook] 1900

>^^Mtwm^^m-i^^^. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/jambalayayearboo05edit WM. 0, ROGERS. JAnBALAYA MDCCCG NEWCOMB COLLWt LIBRARY fi' ^ hP This Book was printed by L. GRAHAM & SON, Ltd. ', '. J New Orleans, La. THAT'S ALL! DEDICATION. To WM- O. ROGERS, Gentleman and Scholar, Secretary of the University, and our Faithful Friend, this, the Fifth Volume of Jambalaya, we dedicate. ^^a^Z. Academical Dbpartment— Page. Photo., Senior Class of 1900 19 Senior Class Officers 20 History of the Class of 1900 21 Statistics of the Class of 1900 23 Junior Class Officers 26 Photo., Junior Class of 1901 27 History of the Class of 1901 28 Statistics of the Class of 1901 30 Sophomore Class, Officers 32 Photo., Sophomore Class of 1902 33 History of the Class of 1902 34 Statistics of the Class of 19U2 36 Freshman Class Officers 38 Photo., Freshman Class of 1903 . 39 History of the Class of 1903 40 Statistics of the Class of 1903 .... 42 Special Students 45 University Department of Philosophy and Science 46 Kewcomb— Senior Class Officers 48 Photo., Senior Class of 1900 49 History of the Class of 1900 50 Statistics of the Class of 1900 53 Junior Class Officers 54 History of the Class of 1901 55 Statistics of the Class of 1901 . 57 Sophomore Class Officers 58 History of the Class of 1902 59 Statistics of the Class of 1902 61 Freshman Class Officers 62 History of the Class of 1903 63 Statistics of the Class of 1903 . -

"Do Unto Others As You Would Have Them Do Unto You": Frederick Douglass's Proverbial Struggle for Civil Rights

"Do Unto Others as You Would Have Them Do Unto You": Frederick Douglass's Proverbial Struggle for Civil Rights Author(s): Wolfgang Mieder Source: The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 114, No. 453 (Summer, 2001), pp. 331-357 Published by: American Folklore SocietyAmerican Folklore Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/542026 Accessed: 01/11/2010 16:28 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=illinois and http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=folk. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Illinois Press and American Folklore Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of American Folklore. -

The Narrative of Lieutenant James Moody

72 Acadiensis Documents The Narrative of Lieutenant James Moody The Narrative of Lieutenant James Moody was first printed in London in 1783. In consequence of a general incredulity, he issued a second edition, supporting it from letters of senior officers under whom he had served. It is the account of one who was described by General James Robertson, civil governor of New York, as "the best partizan" who served the royal cause during the American Revolution. Lorenzo Sabine in his volume of Loyalist biographies allowed Moody but six inches of space in his first edition of 1847. The second edition of 1864 yielded seven pages. "The very name of Moody',' he admitted "became a terror" to supporters of the Rebellion. This candid and highly literate narra tive is the story of a great guerilla fighter who finished his life as a Nova Scotian. Loyalists whose names are remembered in Atlantic history are those who became prominent in colonial politics after 1783. During the actual conflict the fame, or notoriety, of Moody equalled that of any of the future adminis trators who sat at our council tables. A recent American work. Turncoats, Traitors and Heroes by John Bakeless (Philadelphia and New York. 1959), acknowledges with grudging admiration that he was the most remarkable indi vidual serving either side in the capacities of spy and saboteur. To Washington, who was mortified because he could not hang him, he was "that villain Moody" (John J. Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington, vol. 23, p. 444). It is rather astonishing that, having lived in Nova Scotia for twenty-five years, he enjoys no place in provincial historical writing. -

The Echo Makers

cover To find the soul it is necessary to lose it. —A. R. Luria Contents Part One: I Am No One Part Two: But Tonight on North Line Road Part Three: God Led Me To You Part Four: So You Might Live Part Five: And Bring Back Someone Else Part One I Am No One We are all potential fossils still carrying within our bodies the crudities of former existences, the marks of a world in which living creatures flow with little more consistency than clouds from age to age. —Loren Eiseley, The Immense Journey, “The Slit” Cranes keep landing as night falls. Ribbons of them roll down, slack against the sky. They float in from all compass points, in kettles of a dozen, dropping with the dusk. Scores of Grus canadensis settle on the thawing river. They gather on the island flats, grazing, beating their wings, trumpeting: the advance wave of a mass evacuation. More birds land by the minute, the air red with calls. A neck stretches long; legs drape behind. Wings curl forward, the length of a man. Spread like fingers, primaries tip the bird into the wind’s plane. The blood-red head bows and the wings sweep together, a cloaked priest giving benediction. Tail cups and belly buckles, surprised by the upsurge of ground. Legs kick out, their backward knees flapping like broken landing gear. Another bird plummets and stumbles forward, fighting for a spot in the packed staging ground along those few miles of water still clear and wide enough to pass as safe. -

Download Full Book

Staging Governance O'Quinn, Daniel Published by Johns Hopkins University Press O'Quinn, Daniel. Staging Governance: Theatrical Imperialism in London, 1770–1800. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.60320. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/60320 [ Access provided at 30 Sep 2021 18:04 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Staging Governance This page intentionally left blank Staging Governance theatrical imperialism in london, 1770–1800 Daniel O’Quinn the johns hopkins university press Baltimore This book was brought to publication with the generous assistance of the Karl and Edith Pribram Endowment. © 2005 the johns hopkins university press All rights reserved. Published 2005 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 987654321 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data O’Quinn, Daniel, 1962– Staging governance : theatrical imperialism in London, 1770–1800 / Daniel O’Quinn. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8018-7961-2 (hardcover : acid-free paper) 1. English drama—18th century—History and criticism. 2. Imperialism in literature. 3. Politics and literature—Great Britain—History—18th century. 4. Theater—England— London—History—18th century. 5. Political plays, English—History and criticism. 6. Theater—Political aspects—England—London. 7. Colonies in literature. I. Title. PR719.I45O59 2005 822′.609358—dc22 2004026032 A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. -

The Bates Student

Bates College SCARAB The aB tes Student Archives and Special Collections 2-27-1920 The aB tes Student - Magazine Section - volume 48 number 07 - February 27, 1920 Bates College Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/bates_student Recommended Citation Bates College, "The aB tes Student - Magazine Section - volume 48 number 07 - February 27, 1920" (1920). The Bates Student. 546. http://scarab.bates.edu/bates_student/546 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aB tes Student by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. re, e mm xumi . PAGE Editorial Board, 33 King is High, 33 S. IT. W., '20 'George Colby Chase, 43 Israel Jordan, '87 Two He's and a She, 43 David Thompson, '22 Eventide, 46 C. E. W., '20 "Sure Johnny, in a Hurry", 48 I. H., '21 The Admirable Pretense of being Someone You are Not, 50 M. F. II., '21 Old Pal, 55 C. H. K., '20 We Were Just Thinking, 56 s. w. s. From Within Out, 58 WHITE 6 WHITTUM General Insurance and Investment Securities AGENCY ESTABLISHED 1857 165 MAIN ST. Photographs that Please MORRELL & PRINCE AT THE NEW Shoe Dealers HAMMOND STUDIO Reduced Rates to Graduates HAMMOND BROS. 13 Lisbon St., Lewiston, Me. 138 Lisbon St., LEWISTON, ME. Ask for Students' Discount THE FISK TEACHERS' AGENCY Everett O. Fisk & Co., Proprietors Boston, Mass., 2a Park Street Chicago, 111., 28 E. Jackson Blvd. New York, N. -

Download File

Marion Leonard Lived: June 9, 1881 - January 9, 1956 Worked as: film actress, producer, screenwriter Worked In: United States by Sarah Delahousse It is well known that Florence Lawrence, the first “Biograph Girl,” was frustrated in her desire to exploit her fame by the company that did not, in those years, advertise their players’ names. Lawrence is thought to have been made the first motion picture star by an ingenious ploy on the part of IMP, the studio that hired her after she left the Biograph Company. But the emphasis on the “first star” eclipses the number of popular female players who vied for stardom and the publicity gambles they took to achieve it. Eileen Bowser has argued that Lawrence was “tied with” the “Vitagraph Girl,” Florence Turner, for the honorific, “first movie star” (1990, 112). In 1909, the year after Lawrence left Biograph, Marion Leonard replaced her as the “Biograph Girl.” At the end of 1911, Leonard would be part of the trend in which favorite players began to find ways to exploit their popularity, but she went further, establishing the first “star company,” according to Karen Mahar (62). Leonard had joined the Biograph Company in 1908 after leaving the Kalem Company, where she had briefly replaced Gene Gauntier as its leading lady. Her Kalem films no longer exist nor are they included in any published filmography, and few sources touch on her pre-Biograph career. Thus it is difficult to assess her total career. However, Marion Leonard was most likely a talented player as indicated by her rapid ascension to the larger and more prominent studio. -

Library of Congress Motion Picture Conservation Center Quarterly Production Reports, 2000 – 2005

Description of document: The Library of Congress Motion Picture Conservation Center quarterly production reports, 2000 – 2005 Requested date: 20-February-2006 Released date: 22-June-2006 Posted date: 11-January-2008 Title of Document Quarterly Production Report [various periods] Production Report [various periods] Date/date range of document: 16-May-2000 – 13-July-2005 Source of document: The Library of Congress Office Systems Services 101 Independence Avenue, S.E. Washington, D.C. 20540-9440 The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 101 INDEPENDENCE AVENUE, S.E. WASIDNGTON, D.C. 20540-9440 OFFICE SYSTEMS SERVICES June 22, 2006 We acknowledge receipt ofcheck number in the amount of$58.50 for information requested in your letter ofFebruary 20,2006. Enclosed are 83 pages of 1st Quarter 2000 through 2nd Quarter 2005 Motion Picture Conservation Center quarterly production reports. Note that only an annual report was compiled for the time period July 2001 - July 2002 and is included with the quarterly reports requested.