Gone, Missing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Society Sage Pleases Greatly

~ » tell him about vp y V Then Ayer s Cherry I->ec- foral. Tell him how it cured your hard I_/ d n TEN DEAD IN HARPER HAS ^ MCllllr. A Cm if cough. Tell him why you always keep RECORD IS it on hand. Tell him to ask his doctor « it. Doctors use it a , a*> about great deal for /*§ 9* » /> /~C J all forms of throat and lung troubles. We HOTEL FIRE. PASSED AWAY LX A. S i fllj [ We have no secrelsI publish c AyerOo., DELIGHTED. Fire Gave President of Extends Olive Toward Gov- ^Minneapolis Captain Chicago University Twig | 8, 18. 20, 22, 24, 26 and 3o West Fourteenth Street. I to Save Woman- t, 9, ii. Vi. 15. 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23. 24, 25. 27 and 29 West Thirteenth Street, j Claimed Death-Cancer ernor-Tax Attitude in Mes- New York. ^ by _ MRS. MORRIS ___ , "Guests Jump. the Cause. Society sage Pleases Greatly. NEW YORK WEDDING. CNEAPOLIS, Minn., Jnn. 11.— CHICAHO, Jan. II.—William Rainey Corporation Counsel George L A number of people from this city i'est hotel, one of the largest anil of the of IS VERY ILL Record of Jersey City, who has been Sale Harper, president University will attend the marriage ceremony of January liostelrles in has In the front of the fight for equal the country, Chicago, dead at his home here after Miss Gussie Levy, daughter of Mr. here. Ten taxation, is elated over the attitude fcstroyed liy tire per- a long illness of cancer of the intes- and Mrs. -

Talus Corrina Carter Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2016 Talus Corrina Carter Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Carter, Corrina, "Talus" (2016). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 16509. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/16509 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Talus by Corrina Carter A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Major: Creative Writing and Environment Program of Study Committee: K. L. Cook, Major Professor Charissa Menefee Catherine M. McMullen Matthew Sivils Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2016 Copyright © Corrina Carter, 2016. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE................................................................................................................... iii BOOK 1 ……………………………………………………………………………. 1 BOOK II ……………………………………………………………………………. 150 BOOK III …………………………………………………………………………… 228 BOOK IV …………………………………………………………………………… 331 iii PREFACE When, after considering several more literary projects for my thesis, I committed to writing Talus, I realized a grueling research project awaited me. In order to write a successful “talking animal” novel for a young adult audience, I had to revisit the classics of anthropomorphic fiction (my favorite genre as a child), study equine behavior, deepen my knowledge of the mustang controversy, a hot topic in the American West, and learn the natural history of Oregon’s dry side, where my book takes place. -

S E P T E M B E

SEPTEMBER” DINING BECOMES A FINE ART IN THE RENAISSANCE ROOM ^^uncheon's a gay event . dinner is a memorable masterpiece in this distinguished dining-salon at the Gotham. Delicious cuisine temptingly prepared, an impeccable service, charming atmosphere and congenial companionship all con tribute the necessary harmonies to an ensemble that is unex celled. The beautiful Renaissance Room offers a perfect setting for leisurely dining. Spacious, oak-paneled, with rich carvings and deep carpets, the light enters through the vaulted windows with mellow softness. Gayety sparkles in these magic surround ings. That's one of the reasons why people really "live" at the Gotham. Of course the hotel is also famous for its gracious hospitality, large tastefully furnished rooms and its excellent location, convenient to all parts of the city. See how much real comfort awaits you here at a surprisingly moderate rental. Rates from $4.00. Max A. Haering, Resilient Manager FIFTH AVENUE AT FIFTY-FIFTH STREET • NEW YORK CITY Official Headquarters of the 99 Club and Women's National Aeronautical Association FOUR REASONS f o r ^ I R W O T W N ORDERING YOUR FURS NOW * in August you have the pick of the winter pelts . * Leisurely selection . * Savings in workmanship (because up to September 1st work is done CONTENTS at special summer prices) . Laura Ingalls' Record Ship 4 * PELT PRICES HAVE ADVANCED SINCE Scoring Up............................................................ 5 OUR PRESENT STOCK WAS ASSEMBLED Dizzy Depths to Dizzy Heights— By Jeanette AND IT IS UNLIKELY THEY W ILL BE SO LOW AGAIN THIS SEASON . Lempke ........................................... Fay Gillis Invades Ethiopia OUR WINTER MODELS are now being shown Fall Fashion Flashes in the Custom Fur Shop: and The Little Shop of Ready Just Among Us Girls— By Mister Swanee Taylor 8 Furs has reopened with an exceptional collection. -

![Jambalaya [Yearbook] 1900](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7545/jambalaya-yearbook-1900-2707545.webp)

Jambalaya [Yearbook] 1900

>^^Mtwm^^m-i^^^. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/jambalayayearboo05edit WM. 0, ROGERS. JAnBALAYA MDCCCG NEWCOMB COLLWt LIBRARY fi' ^ hP This Book was printed by L. GRAHAM & SON, Ltd. ', '. J New Orleans, La. THAT'S ALL! DEDICATION. To WM- O. ROGERS, Gentleman and Scholar, Secretary of the University, and our Faithful Friend, this, the Fifth Volume of Jambalaya, we dedicate. ^^a^Z. Academical Dbpartment— Page. Photo., Senior Class of 1900 19 Senior Class Officers 20 History of the Class of 1900 21 Statistics of the Class of 1900 23 Junior Class Officers 26 Photo., Junior Class of 1901 27 History of the Class of 1901 28 Statistics of the Class of 1901 30 Sophomore Class, Officers 32 Photo., Sophomore Class of 1902 33 History of the Class of 1902 34 Statistics of the Class of 19U2 36 Freshman Class Officers 38 Photo., Freshman Class of 1903 . 39 History of the Class of 1903 40 Statistics of the Class of 1903 .... 42 Special Students 45 University Department of Philosophy and Science 46 Kewcomb— Senior Class Officers 48 Photo., Senior Class of 1900 49 History of the Class of 1900 50 Statistics of the Class of 1900 53 Junior Class Officers 54 History of the Class of 1901 55 Statistics of the Class of 1901 . 57 Sophomore Class Officers 58 History of the Class of 1902 59 Statistics of the Class of 1902 61 Freshman Class Officers 62 History of the Class of 1903 63 Statistics of the Class of 1903 . -

The Bates Student

Bates College SCARAB The aB tes Student Archives and Special Collections 2-27-1920 The aB tes Student - Magazine Section - volume 48 number 07 - February 27, 1920 Bates College Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/bates_student Recommended Citation Bates College, "The aB tes Student - Magazine Section - volume 48 number 07 - February 27, 1920" (1920). The Bates Student. 546. http://scarab.bates.edu/bates_student/546 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aB tes Student by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. re, e mm xumi . PAGE Editorial Board, 33 King is High, 33 S. IT. W., '20 'George Colby Chase, 43 Israel Jordan, '87 Two He's and a She, 43 David Thompson, '22 Eventide, 46 C. E. W., '20 "Sure Johnny, in a Hurry", 48 I. H., '21 The Admirable Pretense of being Someone You are Not, 50 M. F. II., '21 Old Pal, 55 C. H. K., '20 We Were Just Thinking, 56 s. w. s. From Within Out, 58 WHITE 6 WHITTUM General Insurance and Investment Securities AGENCY ESTABLISHED 1857 165 MAIN ST. Photographs that Please MORRELL & PRINCE AT THE NEW Shoe Dealers HAMMOND STUDIO Reduced Rates to Graduates HAMMOND BROS. 13 Lisbon St., Lewiston, Me. 138 Lisbon St., LEWISTON, ME. Ask for Students' Discount THE FISK TEACHERS' AGENCY Everett O. Fisk & Co., Proprietors Boston, Mass., 2a Park Street Chicago, 111., 28 E. Jackson Blvd. New York, N. -

A Riddle (Pdf)

[Version 4: lines in italics from v. 2 & 3] A Riddle You say I am a riddle – it may be For all of us are riddles unexplained. Begun in pain, in deeper torture ended, This breathing clay what business has it here? Some petty wants to chain us to the Earth, Some lofty thoughts to lift us to the spheres, And cheat us with that semblance of a soul To dream of Immortality, till Time O’er empty visions draws the closing veil, And a new life begins – the life of worms, Those hungry plunderers of the human breast. For this Hope dwindles as we fathom Truth: Forgotten to forget – and is that all? To-day a man, with power to act and feel, A mirror of the Universe, wherein Creation’s centred rays combine to form The focus of Intelligence; to-day A heart so deeply loving that it seems As if that band uniting soul to soul, Were but Religion in a brighter form; To-day all this – to-morrow a cold corpse, A something worse than clay which stinks and rots. Kind hands may strew their flowers, kind eyes may drop A tear of pity o’er the buried dust; But worms will feed long after friends are gone, And, after all, what matters love of theirs 1 When all of us, that was, is at an end. __________________ Thus far we all are riddles, but not so In friendly intercourse of polished men. There never did I shun to show myself In open light – at least the faults I have. -

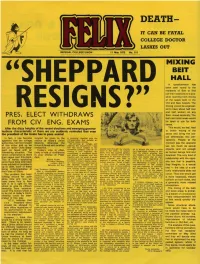

Felix Issue 0307, 1972

DEATH- IT CAN BE FATAL COLLEGE DOCTOR LASHES OUT IMPERIAL COLLEGE UNION 11 May 1972 No. 311 MIXING BEIT HALL SHEPPARD A questionnaire has been sent round to the residents of Beit to find out their reactions to a pos- sible room-by-room mixing of the sexes both in the Old and New hostels. The mixing would be engineer- ed to have about half men RESIGNS?" and half women on any PRES. ELECT WITHDRAWS floor, mixed randomly. The bath and toilet areas would be open to use for both FROM CIV ENG. EXAMS sexes. After the dizzy heights of the recent elections and sweeping general- This would, we feel, lead isations characteristic of them we are suddenly reminded that even to better mixing of the the president of the Union has to pass exams! sexes and bring the sex- siiii- ual differences into per- In fact, it has become support be given to the al potential, together with the apparent that the college motion at today's Union corresponding and suitably at- spective. People at the authorities had not thought Meeting otherwise the tractive career choice. moment see the opposite On arriving at college and .4k of this either and so we Union is faced with another entering the Department I was sex too much as sexual are (or rather Chris Shep- re-election. still very much subject to the somewhat romantic idea of be- sonally and through my involve- ed to accept the way in which objects, and not enough pard is) faced with an Today's vote is effec- ment in the Union, to correct interesting situation. -

Books Music Film Events

FREE FEBRUARY 2014 BOOKS MUSIC FILM EVENTS THE POET’S WIFE MODERN HISTORY OUR MOST ANTICIPATED BOOKS FOR 2014 Krissy Kneen on Mandy Sayer’s Ali Alizadeh on the engrossing new memoir figure of Joan of Arc page 06 page 04 page 06 NEW IN FEBRUARY HANIF BENNY MANDY BLUE BRUCE KUREISHI LINDELAUF SAYER JASMINE SPRINGSTEEN $29.99 $16.99 $33 $39.95 CD $19.95 $27.95 $29.95 CD & DVD $24.95 page 05 page 10 page 10 page 17 page 18 CARLTON 309 Lygon St 9347 6633 HAWTHORN 701 Glenferrie Rd 9819 1917 MALVERN 185 Glenferrie Rd 9509 1952 ST KILDA 112 Acland St 9525 3852 READINGS AT THE STATE LIBRARY OF VICTORIA 328 Swanston St 8664 7540 See shop opening hours, browse and buy online at www.readings.com.au 2 READINGS MONTHLY FEBRUARY 2014 News READINGS NEW AUSTRALIAN range of projects and organisations within WRITING AWARD Victoria in 2014. The successful grant The Readings New Australian Writing recipients for this year are: Award supports published Australian RISE (Refugee Survivors and authors working in fiction, with the vision Ex-Detainees) $20,000 of increasing the promotion and sales of The Wheeler Centre Hot Desk Australian authors’ works to the wider Fellowships $20,000 community. To be eligible for entry in the VACCA (Victorian Aboriginal Child inaugural New Australian Writing Award, Care Agency) $19,760 the book must be the author’s first or second Save the Children $19,990 published work only. The shortlist will be 100 Story Building $15,100 published in the October Readings Monthly, Reading Out of Poverty $15,000 and winning titles will be published in The Stella Prize $10,000 the November issue. -

Module Guide and Diagnostic

SKILLS TO SUCCEED ACADEMY Module Guide and Diagnostic Copyright © 2019 Accenture. All rights reserved. Skills to Succeed Academy, www.s2sacademy.ph. Page | 1 No unauthorized copying or distribution SKILLS TO SUCCEED ACADEMY TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1: Purpose of this Document ............................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Who is this guide for? ...................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 What is this document used for? ..................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Document Overview ........................................................................................................................ 3 Section 2: Pre-Assessment ........................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Scenario Overview ........................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Module recommendations for scenarios .......................................................................................... 4 Section 3: The Training Courses and Modules ............................................................................................. 9 3.1 Training Course and Module Overview ........................................................................................... 9 3.2 Choose a Career Course Modules -

1- Frontpage.Indd

06 The award-winning student newspaper of Imperial College . 11 Guardian Student Newspaper of the Year . 09 Issue 1,443 ffelixelix felixonline.co.uk This week.... Noam Chomsky talks Middle East Facing the annual enemy: The grgreateat political philosopher talks to flu! Imperial PPS and London students, see page 6 Science, Page 13 Hush! A quiet affair at the Royal Albert Hall Nutt sacked Prof. David Nutt fired for criticising the Music, Page 20 government’s deaf ears, see pages 6 & 7 Japanese cinema suprise: Love Exposure Review Film, Page 21 Eating out: Sake No Hana Riposte restaurant review CGCU and RCSU respond to the claims made against them in last week’s issue, see pages 4 & 5 Food, Page 27 2 felix FRIDAY 06 NOVEMBER 2009 News Editor Kadhim Shubber NEWS [email protected] Class of 2010 Councillors elected Afonso Campos reports on a new team to attend Council this year The world beyond ast Friday saw the announce- College walls ment of the Central Union L election results. The newly elected students are now full members of Council. For those un- familiar with the concept, Council is the sovereign policy-making body for our Union; it is a place that tends to Afghanistan encourage democracy and civilised discussion (for the most part) on is- sues that affect students. The newly Hamid Karzai has been declared president of Afghanistan after officials elected members have as their duty to scrapped the second round of voting. represent the views of the student con- The second round, which was due to be held on November 7th, would have stituents of their Faculty and do so at seen Hamid Karzai pitted against his main rival, Abdullah Abdullah, but the monthly meetings. -

No Ordinary World Duran Duran’S Simon Le Bon Hungry to Keep Audiences Dancing Zoe-Ruth Photography

VOLUME 10, NUMBER 5 NUMBER 10, VOLUME NO ORDINARY WORLD DURAN DURAN’S SIMON LE BON HUNGRY TO KEEP AUDIENCES DANCING ZOE-RUTH PHOTOGRAPHY 418 Sheridan Road Highland Park, IL 60035 847-266-5000 www.ravinia.org Welz Kauffman President and CEO Nick Pullia Communications Director, Executive Editor Nick Panfl Publications Manager, Editor Alexandra Pikeas Graphic Designer IN THIS ISSUE FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Since 1991 12 Practice Room with a View 9 Message from the Chairman 3453 Commercial Ave., Northbrook, IL 60062 Te Juilliard Quartet’s Joseph Lin and and President www.performancemedia.us | 847-770-4620 Astrid Schween prepare musicians for 31 Rewind Gail McGrath - Publisher & President more than the concert stage. Sheldon Levin - Publisher & Director of Finance By Wynne Delacoma 50 Ravinia’s Steans Music Institute 18 Grateful Eternal Account Managers 52 Reach*Teach*Play Jerry Garcia and the Grateful Dead Rand Brichta - Arnie Hoffman - Greg Pigott made music for all time. 57 Salute to Sponsors Southwest By Davis Schneiderman Betsy Gugick & Associates 972-387-1347 24 No Ordinary World 73 Annual Fund Donors Duran Duran’s Simon Le Bon is hungry Sales & Marketing Consultant 80 Corporate Partners to keep audiences dancing. Mike Hedge 847-770-4643 81 Corporate Matching Gifs David L. Strouse, Ltd. 847-835-5197 By Miriam Di Nunzio 34 ‘Home Schooled’ 82 Special Gifs Cathy Kiepura - Graphic Designer Jonathan Biss and Pamela Frank recall Lory Richards - Graphic Designer their master classes in growing up as 83 Event Sponsors A.J. Levin - Director of Operations (and with) musicians. 84 Board of Trustees Josie Negron - Accounting By Mark Tomas Ketterson 85 Women’s Board Joy Morawez - Accounting 40 Unplugged, Unbound Willie Smith - Supervisor Operations Chris Cornell fnds ‘higher truth’ 86 Associates Board Earl Love - Operations in his music by going acoustic. -

Bare Facts, Issue No. 895, 13.12.1996

4 The Issue No. 895 University of 13th December 1996 Surrey Students' Paper Christmas Issue CandleUt Vigil To Be Held At LSE dlelit chain from the LSE on the Aldwych Sam Parham, LSE Education and Welfare tudents will hold a candlelit to the meeting venue, Clements House. Officer, said: "We are expecting a good vigil from 4pin on Thursday tumout for this protest. Feeling is running S12th December outside the The LSE is a front runner in the race to high among students who are fearfiil the London School of Economics in a charge students top up fees, even though LSE will be the first college to implement solemn protest against Govemors student cannot afford to pick up the bill fees. I know many people here who for the underfunding of hìgher education. wouldn't be able to pay tuition fees and who will be deciding whether to Charging fees will cause considerable who would be put off entering higher implement fees of up to £1,000, damage to the reputation the LSE has for education completely if fees b«came a despite last week's announcement excellence. Access to the college will reality. Fees will mean an end to access at ^ vice-chancellors to reject fees. only be for those from well-off back- LSE." The vigil will be supported by students groimds. LSE Govemors are being urged to take the concems of students seriously across the country who will forni a can- and reject fees once and for ali. Editor's Bit Review of 1996 - CONTENTS My Life As A Sabb riginally I was had to get that one in) and the return of the students.