Marxism, History and Socialist Consciousness: a Reply by David North to Alex Steiner and Frank Brenner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friday, May 8, 2009

Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology Rose-Hulman Scholar The Rose Thorn Archive Student Newspaper Spring 5-8-2009 Volume 44 - Issue 25 - Friday, May 8, 2009 Rose Thorn Staff Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn Recommended Citation Rose Thorn Staff, "Volume 44 - Issue 25 - Friday, May 8, 2009" (2009). The Rose Thorn Archive. 154. https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn/154 THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS ROSE-HULMAN REPOSITORY IS TO BE USED FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP, OR RESEARCH AND MAY NOT BE USED FOR ANY OTHER PURPOSE. SOME CONTENT IN THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT. ANYONE HAVING ACCESS TO THE MATERIAL SHOULD NOT REPRODUCE OR DISTRIBUTE BY ANY MEANS COPIES OF ANY OF THE MATERIAL OR USE THE MATERIAL FOR DIRECT OR INDIRECT COMMERCIAL ADVANTAGE WITHOUT DETERMINING THAT SUCH ACT OR ACTS WILL NOT INFRINGE THE COPYRIGHT RIGHTS OF ANY PERSON OR ENTITY. ANY REPRODUCTION OR DISTRIBUTION OF ANY MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY IS AT THE SOLE RISK OF THE PARTY THAT DOES SO. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspaper at Rose-Hulman Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rose Thorn Archive by an authorized administrator of Rose-Hulman Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. T HE R OSE T HORN R OSE -H ULMAN I NSTITUTE OF T ECHNOLOGY T ERRE H AUTE , I NDIANA FRIDAY, MAY 8, 2009 ROSE-HULMAN.EDU/THORN/ VOLUME 43, ISSUE 25 Greek Games a success News Briefs Lindsey Saxton from campus safety and fa- By Andy Klusman Advertising cilities-- shutting down the M a n a g e r roads and providing tables.” Barron also said, “This year, Dom DeLuise n May 3rd, over 250 we wanted to entice more Rose students gath- people to come out and par- dead at 75 Oered to uphold an ticipate, so we made t-shirts Actor Dom DeLuise died Monday night honored Greek tradition, the to help advertise, and these in a Los Angeles hospital. -

CALIFORNIA's NORTH COAST: a Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors

CALIFORNIA'S NORTH COAST: A Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors. A Geographically Arranged Bibliography focused on the Regional Small Presses and Local Authors of the North Coast of California. First Edition, 2010. John Sherlock Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian University of California, Davis. 1 Table of Contents I. NORTH COAST PRESSES. pp. 3 - 90 DEL NORTE COUNTY. CITIES: Crescent City. HUMBOLDT COUNTY. CITIES: Arcata, Bayside, Blue Lake, Carlotta, Cutten, Eureka, Fortuna, Garberville Hoopa, Hydesville, Korbel, McKinleyville, Miranda, Myers Flat., Orick, Petrolia, Redway, Trinidad, Whitethorn. TRINITY COUNTY CITIES: Junction City, Weaverville LAKE COUNTY CITIES: Clearlake, Clearlake Park, Cobb, Kelseyville, Lakeport, Lower Lake, Middleton, Upper Lake, Wilbur Springs MENDOCINO COUNTY CITIES: Albion, Boonville, Calpella, Caspar, Comptche, Covelo, Elk, Fort Bragg, Gualala, Little River, Mendocino, Navarro, Philo, Point Arena, Talmage, Ukiah, Westport, Willits SONOMA COUNTY. CITIES: Bodega Bay, Boyes Hot Springs, Cazadero, Cloverdale, Cotati, Forestville Geyserville, Glen Ellen, Graton, Guerneville, Healdsburg, Kenwood, Korbel, Monte Rio, Penngrove, Petaluma, Rohnert Part, Santa Rosa, Sebastopol, Sonoma Vineburg NAPA COUNTY CITIES: Angwin, Calistoga, Deer Park, Rutherford, St. Helena, Yountville MARIN COUNTY. CITIES: Belvedere, Bolinas, Corte Madera, Fairfax, Greenbrae, Inverness, Kentfield, Larkspur, Marin City, Mill Valley, Novato, Point Reyes, Point Reyes Station, Ross, San Anselmo, San Geronimo, San Quentin, San Rafael, Sausalito, Stinson Beach, Tiburon, Tomales, Woodacre II. NORTH COAST AUTHORS. pp. 91 - 120 -- Alphabetically Arranged 2 I. NORTH COAST PRESSES DEL NORTE COUNTY. CRESCENT CITY. ARTS-IN-CORRECTIONS PROGRAM (Crescent City). The Brief Pelican: Anthology of Prison Writing, 1993. 1992 Pelikanesis: Creative Writing Anthology, 1994. 1994 Virtual Pelican: anthology of writing by inmates from Pelican Bay State Prison. -

Sample Ballot

SAMPLE BALLOT SKAGIT COUNTY WA GENERAL ELECTION NOVEMBER 2, 2004 INSTRUCTIONS 1. Only use pencil to mark your ballot. PROPOSED TO THE LEGISLATURE STATE STATE 2. You must completely blacken the oval to AND REFERRED TO THE PEOPLE: INITIATIVE TO THE LEGISLATURE 297 the left of your desired selection. Initiative Measure No. 297 concerns GOVERNOR ATTORNEY GENERAL "mixed" radioactive and nonradioactive 4 Year Term 4 Year Term 3. To write-in a candidate you must write hazardous waste. This measure would Vote For One Vote For One their name and party on the line provided add new provisions concerning "mixed" under the desired position. radioactive and nonradioactive hazardous waste, requiring cleanup of contamination 4. Do not make any identifying marks on before additional waste is added, Christine Gregoire D Deborah Senn D your ballot. prioritizing cleanup, providing for public participation and enforcement through ABBREVIATION POLITICAL PARTY citizen lawsuits. Dino Rossi R Rob McKenna R D Democratic Should this measure be enacted into law? R Republican L Libertarian Ruth Bennett L J. Bradley Gibson L WW Workers World Yes G Green SW Socialist Workers Paul Richmond G C Constitution No SE Socialist Equality Write-in I Independent Candidate NP Nonpartisan Write-in PROPOSED BY INITIATIVE PETITION: FEDERAL LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR INITIATIVE TO THE PEOPLE 872 4 Year Term Initiative Measure No. 872 concerns Vote For One elections for partisan offices. This PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT COMMISSIONER OF PUBLIC LANDS measure would allow voters to select OF THE UNITED STATES 4 Year Term among all candidates in a primary. 4 Year Term Vote For One Ballots would indicate candidates' party Vote For One Brad Owen D preference. -

Contemporary Left Antisemitism

“David Hirsh is one of our bravest and most thoughtful scholar-activ- ists. In this excellent book of contemporary history and political argu- ment, he makes an unanswerable case for anti-anti-Semitism.” —Anthony Julius, Professor of Law and the Arts, UCL, and author of Trials of the Diaspora (OUP, 2010) “For more than a decade, David Hirsh has campaigned courageously against the all-too-prevalent demonisation of Israel as the one national- ism in the world that must not only be criticised but ruled altogether illegitimate. This intellectual disgrace arouses not only his indignation but his commitment to gather evidence and to reason about it with care. What he asks of his readers is an equal commitment to plumb how it has happened that, in a world full of criminality and massacre, it is obsessed with the fundamental wrongheadedness of one and only national movement: Zionism.” —Todd Gitlin, Professor of Journalism and Sociology, Columbia University, USA “David Hirsh writes as a sociologist, but much of the material in his fascinating book will be of great interest to people in other disciplines as well, including political philosophers. Having participated in quite a few of the events and debates which he recounts, Hirsh has done a commendable service by deftly highlighting an ugly vein of bigotry that disfigures some substantial portions of the political left in the UK and beyond.” —Matthew H. Kramer FBA, Professor of Legal & Political Philosophy, Cambridge University, UK “A fierce and brilliant rebuttal of one of the Left’s most pertinacious obsessions. What makes David Hirsh the perfect analyst of this disorder is his first-hand knowledge of the ideologies and dogmata that sustain it.” —Howard Jacobson, Novelist and Visiting Professor at New College of Humanities, London, UK “David Hirsh’s new book Contemporary Left Anti-Semitism is an impor- tant contribution to the literature on the longest hatred. -

Tory Councillor Calls for Jeremy Corbyn to Be Hanged As Bogus Anti-Semitism Campaign Intensifies

World Socialist Web Site wsws.org Tory councillor calls for Jeremy Corbyn to be hanged as bogus anti-Semitism campaign intensifies By Robert Stevens 27 July 2019 On Wednesday, as Boris Johnson became prime minister, part of the problem. We have to stand for a serious, a Lincolnshire Conservative councillor, Roger Patterson, anti-racist, inclusive socialism.” tweeted that Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn was a Such was the Corbynites’ capitulation that after giving her “traitor” and supporter of terrorism who should be report outlining the new disciplinary measures to the “swinging from the gallows like Saddam Hussein.” Parliamentary Labour Party that evening, Formby received a Patterson has been suspended. But the campaign led by standing ovation. The following day Labour’s NEC backed Labour’s right wing and various Zionist groups accusing the plans for “legally robust rules” to be presented for Corbyn and the “left” of anti-Semitism has played a central adoption at Labour’s annual conference in September. role in creating the political climate for incitement to Corbyn and his backers have agreed to the disciplinary violence. Just two weeks earlier, Patterson tweeted, “The measures, even though everyone knows the claims of the only minorities to be cleansed are Corbyn’s terrorist Blairites and Zionists are a pack of lies. The text of the NEC sympathising anti semitic cult. They are a dirty stain on this ruling stated, “Anti-Semitism complaints relate to a small country.” minority of members,” and even this massively distorts the Corbyn has faced warnings of an armed forces mutiny if real picture. -

Vienna Page 8

and Oakton Vienna Page 8 Classifieds, Page 14 Classifieds, ❖ Sports, Page 13 ❖ A Fountain of Entertainment, Page 10 ❖ Black History Comedy Club News, Page 3 Opinion, Page 6 Opens in Vienna News, Page 3 David North directs the Mosaic Harmony chorus. Vienna’s The chorus has been singing inspirational songs in the black gospel music style since 1993, with its base at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Historic Fairfax (UUCF) in Oakton. Love Story News, Page 4 #86 PERMIT Martinsburg, WV Martinsburg, PAID U.S. Postage U.S. PRSRT STD PRSRT Photo by David York by David Photo www.ConnectionNewspapers.comFebruary 15-21, 2012 onlineVienna/Oakton at www.connectionnewspapers.com Connection ❖ February 15-21, 2012 ❖ 1 2 ❖ Vienna/Oakton Connection ❖ February 15-21, 2012 www.ConnectionNewspapers.com Vienna/Oakton Connection Editor Kemal Kurspahic 703-778-9414 or [email protected] News Comedy Club Opens in Vienna Mosaic Harmony The Back by Photo performs at nursing homes and assisted Room really is a living facilities Donna Manz throughout the Wash- back room. ington area. By Donna Manz The Connection /The Connection To its list of social events, Vienna has now added “comedy Photo by club.” Called The Back Room, David York and housed in a back room of Marco Polo Restaurant on Maple Avenue Friday nights, the venue opened in mid-De- Former Vienna resident A Fountain of Black History cember. Owner and talent scout Andrew Sanderson Andy Sanderson, who grew up returned to the town he references to “Lord” but few to Christ, Jesus or the in Vienna, wanted a place grew up in to open a Mosaic Harmony promotes cross. -

Backgrounder January 2013

Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder January 2013 Migration Enforcement Agency Discourages Funds for Its Own Work By David North iven that would-be Wall Street bomber Quazi Mohammed Nafis had a student visa,1 as did Times Square bomber Faisal Shahzad2 and as did the 9/11 pilots Mohamed Atta and Marwan Al-Shehhi 11 years earlier,3 perhaps it is time to look a little more closely at the sleepy agency that regulates the educational Gbodies that play host to foreign students, the Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP). SEVP is a subset of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which, in turn, is part of the Department of Homeland Security. An educational institution cannot cause the admission of aliens without getting the general authority to do so from SEVP. ICE is also supposed to stop the operations of visa mills, store-front entities that collect tuition from aliens in exchange for visas, but do not, in fact, offer any education. It turns out that SEVP is an immigration enforcement agency that sometimes complains about a lack of funds4 to do its job, but that consistently refuses to spend money allocated to it, and refuses to raise the fees that would solve its own funding problems. That those people who either did, or wanted to, spread death and destruction in Manhattan had used student visas is generally known, but little has been written on the structure, and strange funding, of SEVP. Generally, it appears that: • There are a massive number of foreign students; SEVP puts the current number of students and their dependents at close to 1.2 million,5 many of whom will stay here for the rest of their lives, some legally and some illegally. -

David Ray Griffin Foreword by Richard Folk

THE NEW PEARL HARBOR Disturbing Questions about the Bush Administration and 9/11 by David Ray Griffin foreword by Richard Folk CONTENTS Acknowledgements vi Forword by Richard Falk vii Introduction xi PART ONE THE EVENTS OF 9 / 11 1. Flights 11 and 175: How Could the Hijackers' Missions Have Succeeded? 3 2. Flight 77: Was It Really the Aircraft that Struck the Pentagon? 25 3. Flight 93: Was It the One Flight that was Shot Down? 49 4. The Presidents Behavior. Why Did He Act as He Did? 57 PART TWO THE LARGER CONTEXT 5. Did US Officials Have Advance Information about 9/11? 67 6. Did US Officials Obstruct Investigations Prior to 9/11? 75 7. Did US Officials Have Reasons for Allowing 9/11? 89 8. Did US Officials Block Captures and Investigations after 9/11? 105 PART THREE CONCLUSION 9. Is Complicity by US Officials the Best Explanation? 127 10. The Need for a Full Investigation 147 Notes 169 Index of Names 210 Back Cover Text OLIVE BRANCH PRESS An imprint of Interlink Publishing Group, Inc. Northampton, Massachusetts First published in 2004 by OLIVE BRANCH PRESS An imprint of Interlink Publishing Group, Inc. 46 Crosby Street, Northampton, Massachusetts 01060 www.interlinkbooks.com Text copyright © David Ray Griffin 2004 Foreword copyright © Richard Falk 2004 All rights reserved. No pan of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher unless National Security in endangered and education is essential for survival people and their nation . -

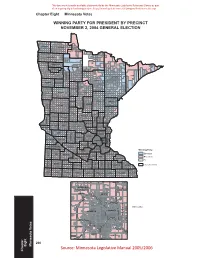

Source: Minnesota Legislative Manual 2005/2006 Chapter Minnesota Votes Chapter Eight

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/mngov/electionresults.aspx Chapter Eight Minnesota Votes WINNING PARTY FOR PRESIDENT BY PRECINCT NOVEMBER 2, 2004 GENERAL ELECTION Metro area 290 Eight Votes Minnesota Source: Minnesota Legislative Manual 2005/2006 Chapter Minnesota Votes Chapter Eight WINNING PARTY FOR U.S. REPRESENTATIVE BY PRECINCT NOVEMBER 2, 2004 GENERAL ELECTION Metro area 291 Eight Votes Minnesota Chapter Chapter Eight Minnesota Votes STATE SENATE DISTRICTS BY PARTY, JANUARY 3, 2005 292 Eight Votes Minnesota Chapter Minnesota Votes Chapter Eight STATE SENATE DISTRICTS BY PARTY, JANUARY 3, 2005 Metro area 293 Eight Votes Minnesota Chapter Chapter Eight Minnesota Votes STATE HOUSE DISTRICTS BY PARTY, JANUARY 3, 2005 294 Eight Votes Minnesota Chapter Minnesota Votes Chapter Eight STATE HOUSE DISTRICTS BY PARTY, JANUARY 3, 2005 Metro area 295 Eight Votes Minnesota Chapter Chapter Eight Minnesota Votes VOTING SYSTEMS USED BY PRECINCT NOVEMBER 2, 2004 GENERAL ELECTION Hand Counted: Ballots are counted by hand after the polls close (roughly 17% of polling places, containing 4% of voters) Centrally Counted Optical Scan: Ballots are scanned and tabulated at a central location in the county after the polls close (roughly 37% of precincts, containing 16% of voters) Precinct-Based Optical Scan: Voters put their ballots into a scanner in the polling place (roughly 46% of polling places, containing 80% of -

Jean Shaoul Is Professor of Public Accountability at the University of Manchester, Uk

“Neo-liberalism” Professor Jean Shaoul Manchester Business School, The University of Manchester, UK Abstract While there have been many reviews of neo-liberalism, there have been few attempts to explain its source and development within the workings of the economic systems itself and understand it as an expression of the crisis of the profit system as a whole and the correlation of class forces. This paper by way of contrast explains neo-liberalism not simply as a policy choice but as the response of big business and their political representatives to economic and technological changes taking place in world economy. Their ability to implement such policies was directly bound up with the absence of a politically conscious movement in the working class as the socialist conceptions that animated large sections of workers in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution came under attack from Stalinism, labour reformism and trade unionism, which together attacked genuine socialism and above all internationalism After analyzing the assumptions and policy prescriptions of the widespread opposition movements, the paper argues for revolutionary scientific socialism as opposed to the dominant, politically liberal, programme of national reformism – which is why the traditional organizations of the working class and intellectuals have been unable to mount any effective opposition or critique of the neo-liberal agenda. Jean Shaoul is professor of public accountability at the University of Manchester, Uk. She has written on privatisation and the use of private finance in transport and healthcare. She is a regular contributor to the World Socialist web Site (www.wsws.org) . -

Building Permits Issued

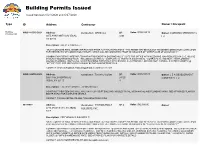

Building Permits Issued Issued between 6/21/2020 and 6/27/2020 Type ID Address Contractor Owner / Occupant Building BUILD-005503-2020 Address: SF: Value: $199,355.30 (Commercial) Contractor : MRED LLC Owner: DIAMOND SPEEDWAY L 6075 ANN NORTH LAS VEGAS, 3206 L C NV 89115 Description: KOLAY FLOORING - TI *MUST COMPLETE FINAL SEWER VERIFICATION PRIOR TO FINAL INSPECTIONS**THIS PERMIT MAY BE SUBJECT TO SEWER CONNECTION COSTS UPON FURTHER REVIEW OF CONNECTION HISTORY, WHICH WILL BE COMPLETED PRIOR TO ISSUANCE OF "CERTIFICATE OF OCCUPANCY".* COMBINATION PERMIT: INTERIOR TENANT IMPROVEMENT IN EXISTING 3406 SF SUITE FOR OFFICE WITH MEZZANINE. QAA REQUIRED ON C, G, XB & XE BY BLACK MOUNTAIN GEO TECH. INCLUDES ELECTRICAL - COMPLETE AC AND HEAT, MECHANICAL - COMPLETE AC AND HEAT, AND PLUMBING - LOUNGE PLUMBING. INSTALLING 14 NEW PLUMBING FIXTURES (1 KITCHEN SINK, 6 LAVATORIES, 1 SERVICE MOP, 1 URINAL, 5 WATER CLOSETS) @ "OFFICE" RATE. SEE APPROVED PLANS BY BV FOR COMPLETE DETAILS. CONTACT: IGNACIO ROBLES [email protected] BUILD-006779-2020 Address: Contractor : Timothy Walker SF: Value: $135,938.00 Owner: L S A DEVELOPMENT 5801 NICCO NORTH LAS 34125 COMPANY L L C VEGAS, NV 89115 4 Description: LSA DEVELOPMENT - DEMISING WALL CONSTRUCT NEW DEMISING WALL ONLY IN 341,254 SQ FT BUILDING. NO ELECTRICAL, MECHANICAL AND PLUMBING WORK. SEE APPROVED PLANS BY EDGAR SURLA FOR COMPLETE DETAILS. CONTACT: TIM WALKER 702-310-6088 [email protected] BD177957 Address: Contractor : PERFORMANCE SF: 0 Value: $82,000.00 Owner: 4275 ARCATA NLV, NV 89030- BUILDERS, INC. 3317 Description: PERFORMANCE BUILDERS -TI *MUST COMPLETE FINAL SEWER VERIFICATION PRIOR TO FINAL INSPECTIONS**THIS PERMIT MAY BE SUBJECT TO SEWER CONNECTION COSTS UPON FURTHER REVIEW OF CONNECTION HISTORY, WHICH WILL BE COMPLETED PRIOR TO ISSUANCE OF "CERTIFICATE OF OCCUPANCY".* COMBINATION PERMIT: 13,266 INTERIOR TENANT IMPROVEMENT TO CREATE ADDITIONAL OFFICE SPACES AND 2( ) RESTROOMS. -

The Carnival King of Capital

Fast Capitalism ISSN 1930-014X Volume 17 • Issue 1 • 2020 doi:10.32855/fcapital.202001.006 The Carnival King of Capital Charles Thorpe Introduction: The Carnival King Brookings Institute writers Susan Hennessy and Benjamin Wittes complain that, while in the past, Presidents were expected to show certain standards of virtue and decency, Donald Trump’s life and candidacy were an ongoing rejection of civic virtue…. From the earliest days of his campaign, he declared war on the traditional presidency’s expectations of behavior. He was flagrant in his immorality, boasting of marital infidelity and belittling political opponents with lewd insults. He had constructed his entire professional identity around gold-plated excess and luxury and the branding of self. As a candidate, he remained unabashed in his greed and personal ambition; even his namesake charitable foundation was revealed to be merely a shell for self-dealing. He bragged that finding ways to avoid paying taxes made him “smart.”…He never spoke of the presidential office other than as an extension of himself (Hennessey and Wittes, 2020: 6-7). This description suggests that Trump represents a demoralization and deinstitutionalization of the role of President. Trump brings a condition of anomie to the Presidency, and this anomie is closely related to the trait of narcissism that Trump exhibits in spades (Merton, 1938; Frank, 2018). Hennessey and Wittes encapsulate what Trump signifies when they write that “The overriding message of Trump’s life and of his campaign was that kindness is weakness, manners are for wimps, and the public interest is for suckers” (Hennessey and Wittes 2020: 6-7).