French Missionary Expansion in Colonial Upper Tonkin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory Pictures in a Time of Defeat: Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory pictures in a time of defeat: depicting war in the print and visual culture of late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/18449 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. VICTORY PICTURES IN A TIME OF DEFEAT Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884-1901 Yin Hwang Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the History of Art 2014 Department of the History of Art and Archaeology School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 2 Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. -

DP - D 1-8 D 1-8 - Missionnaires

AHDP - D 1-8 D 1-8 - Missionnaires Prêtres, religieux, religieuses et laïcs originaires du diocèse de Poitiers A Aguillon, Bernard D 1-8 boîte 2-5 Albert, Marthe D 1-8 boîte 2-6 Alberteau, Yves D 1-8 boîte 2-5 Allain, Antoine-Marie D 1-8 boîte 2-11 Allard, Michel D 1-8 boîte 2-5 Archambaud, Eugène D 1-8 boîte 2-9 Audebert, Madeleine D 1-8 boîte 2-6 Audoux, Marie-Louise D 1-8 boîte 2-6 Augouard, Prosper D 1-8 boîte 2-13 Auneveux, Jean D 1-8 boîte 2-11 Auzanneau, Joseph D 1-8 boîte 2-3 B Barbier, Narcisse D 1-8 boîte 2-4 Barge, Jean D 1-8 boîte 2-9 Baron, Gérard D 1-8 boîte 2-13 Baron, Jean-Joseph D 1-8 boîte 2-9 Baron, Léone D 1-8 boîte 2-6 Baron, Odile D 1-8 boîte 2-6 Barrois, Louis D 1-8 boîte 2-4 Barré, Anne-Marie D 1-8 boîte 2-11 Baudin, Marie D 1-8 boîte 2-6 Baudu, Pierre D 1-8 boîte 2-5 Baufreton, Charles D 1-8 boîte 2-4 Bazin, Séraphin D 1-8 boîte 2-7 Beauregard Savary, Marthe (de) D 1-8 boîte 2-11 Bédin, Denise D 1-8 boîte 2-6 Bédin, Thérèse D 1-8 boîte 2-6 Beillerot, Joseph D 1-8 boîte 2-5 Beliveau, Annie D 1-8 boîte 2-11 Bellécullée, Marie-Pierre D 1-8 boîte 2-6 Bellenger, Marie-Joseph D 1-8 boîte 2-6 Belloc, Jean D 1-8 boîte 2-5 Bellouard, Joseph D 1-8 boîte 2-3 Benoist, Monique D 1-8 boîte 2-6 Berger, Marie-Adrien D 1-8 boîte 2-1 Bernier, Anne-Marie D 1-8 boîte 2-6 Bernier, Thérèse D 1-8 boîte 2-6 Bertaud, Anne-Marie D 1-8 boîte 2-6 Berthon, Jean-Baptiste D 1-8 boîte 2-9 Bertonneau, Michel D 1-8 boîte 2-5 Bertrand-Guicheteau, Miguel D 1-8 boîte 2-11 Besson, Georges D 1-8 boîte 2-5 Billaud, Agnès-Marie D 1-8 boîte 2-9 Billaud, -

(FCPE 95) 5 Pl

Institution Adresse Ville Code Postal Département FÉDÉRATION DES CONSEILS DE PARENTS D'ÉLÈVES DU VAL-D'OISE 5 Place des Linandes CERGY 95000 95 (FCPE 95) FÉDÉRATION DES CONSEILS DE PARENTS D'ÉLÈVES DU VAL-D'OISE 5 Place des Linandes CERGY 95000 95 (FCPE 95) INDECOSA CGT 95 26, Rue Francis Combe CERGY 95000 95 ASSOCIATION DES USAGERS DES TRANSPORTS (AUT) 16 Rue Raspail ARGENTEUIL 95100 95 D’ARGENTEUIL CGL 95 62 Rue du Lieutenant Colonel Prudhon ARGENTEUIL 95100 95 CNL 95 1 allée Hector Berlioz ARGENTEUIL 95100 95 UFC QUE CHOISIR 95 82 Boulevard du Général Leclerc ARGENTEUIL 95100 95 INITIATIVES ET ACTIONS POUR LA SAUVEGARDE DE Centre associatif François Bonn L'ISLE-ADAM 95290 95 L'ENVIRONNEMENT ET DES FORÊTS (IASEF) UNION DES MAIRES DU VAL-D'OISE 38 Rue de la coutellerie PONTOISE 95300 95 AFOC 95 38 Rue d'Eragny SAINT OUEN L'AUMONE 95310 95 VAL D'OISE ENVIRONNEMENT 19 allée du lac DOMONT 95330 95 LES AMIS DE LA TERRE DU VAL D’YSIEUX 5 Rue de la source FOSSES 95470 95 FAMILLE DE FRANCE 95 9 allée des Coquelicots OSNY 95520 95 LES AMIS DU VEXIN FRANÇAIS Château de Théméricourt THEMERICOURT 95540 95 LES AMIS DE LA TERRE DU VAL-D’OISE 31 Rue Gaëtan Pirou ANDILLY 95580 95 FAMILLE LAIQUE 95 30 allée Julien Manceau MARGENCY 95590 95 CSF 95 26 Rue Seny EAUBONNE 95600 95 SAUVEGARDE-VEXIN-SAUSSERON Mairie NESLES-LA-VALLÉE 95690 95 FÉDÉRATION DU VAL D'OISE POUR LA PÊCHE ET DE LA 28 Rue du Général de Gaulle GRISY-LES-PLÂTRES 95810 95 PROTECTION DU MILIEU AQUATIQUE MAIRIE DE NEUVILLE SUR OISE 65 Rue joseph cornudet NEUVILLE SUR OISE 95000 95 ECOLE -

I Politics and Practices of Conservation Governance and Livelihood Change in Two Ethnic Hmong Villages and a Protected Area In

Politics and practices of conservation governance and livelihood change in two ethnic Hmong villages and a protected area in Yên Bái province, Vietnam. Bernhard Huber Department of Geography McGill University, Montreal A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Bernhard Huber 2019 i Abstract What happens in a remote village of traditional shifting cultivators and hunters when, in the course of twenty years, traditional livelihood practices are banned, alternative income opportunities emerge, a protected area is established, and selected villagers are paid to patrol fellow villagers’ forest use? In this thesis, I aim to investigate how ethnic Hmong villagers in Mù Cang Chải district, Yên Bái Province, Vietnam, and their livelihood practices have intersected with outside interventions for rural development and forest conservation since 1954. Addressing five research questions, I examine historical livelihood changes, contemporary patterns of wealth and poverty, the institutionalisation of forest conservation, the village politics of forest patrolling and hunting, as well as the local outcomes of Vietnam’s nascent Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) program. I find that these aspects vary significantly within and between two Hmong villages, in which I collected most of my data. The forced transition in the 1990s from shifting cultivation to paddy cultivation increased food security, but has also resulted in new patterns of socio-economic differentiation, as some households had limited access to paddy land. More recently, socio-economic differentiation has further increased, as households have differently benefited from PES, government career opportunities and bank loans. These sources of financial capital are increasingly relevant to peasant livelihoods elsewhere in Vietnam, but remain largely under-studied. -

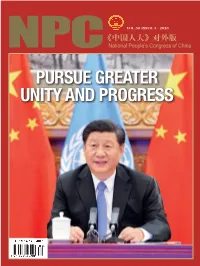

Pursue Greater Unity and Progress News Brief

VOL.50 ISSUE 3 · 2020 《中国人大》对外版 NPC National People’s Congress of China PURSUE GREATER UNITY AND pROGRESS NEWS BRIEF President Xi Jinping attends a video conference with United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres from Beijing on September 23. Liu Weibing 2 NATIONAL PEOPle’s CoNGRESS OF CHINA ISSUE 3 · 2020 3 6 Pursue greater unity and progress Contents UN’s 75th Anniversary CIFTIS: Global Services, Shared Prosperity National Medals and Honorary Titles 6 18 26 Pursue greater unity Global services, shared prosperity President Xi presents medals and progress to COVID-19 fighters 22 9 Shared progress and mutually Special Reports Make the world a better place beneficial cooperation for everyone 24 30 12 Accelerated development of trade in Work together to defeat COVID-19 Xi Jinping meets with UN services benefits the global economy and build a community with a shared Secretary-General António future for mankind Guterres 32 14 Promote peace and development China’s commitment to through parliamentary diplomacy multilateralism illustrated 4 NATIONAL PEOPle’s CoNGRESS OF CHINA 42 The final stretch Accelerated development of trade in 24 services benefits the global economy 36 Top legislator stresses soil protection ISSUE 3 · 2020 Fcous 38 Stop food waste with legislation, 34 crack down on eating shows Top legislature resolves HKSAR Leg- VOL.50 ISSUE 3 September 2020 Co vacancy concern Administrated by General Office of the Standing Poverty Alleviation Committee of National People’s Congress 36 Top legislator stresses soil protection Chief Editor: Wang Yang General Editorial 42 Office Address: 23 Xijiaominxiang, The final stretch Xicheng District, Beijing 37 100805, P.R.China Full implementation wildlife protection Tel: (86-10)5560-4181 law stressed (86-10)6309-8540 E-mail: [email protected] COVER: President Xi Jinping ad- ISSN 1674-3008 dresses a high-level meeting to CN 11-5683/D commemorate the 75th anniversary Price: RMB 35 of the United Nations via video link Edited by The People’s Congresses Journal on September 21. -

Special Issue 2, August 2015

Special Issue 2, August 2015 Published by the Center for Lao Studies ISSN: 2159-2152 www.laostudies.org ______________________ Special Issue 2, August 2015 Information and Announcements i-ii Introducing a Second Collection of Papers from the Fourth International 1-5 Conference on Lao Studies. IAN G. BAIRD and CHRISTINE ELLIOTT Social Cohesion under the Aegis of Reciprocity: Ritual Activity and Household 6-33 Interdependence among the Kim Mun (Lanten-Yao) in Laos. JACOB CAWTHORNE The Ongoing Invention of a Multi-Ethnic Heritage in Laos. 34-53 YVES GOUDINEAU An Ethnohistory of Highland Societies in Northern Laos. 54-76 VANINA BOUTÉ Wat Tham Krabok Hmong and the Libertarian Moment. 77-96 DAVID M. CHAMBERS The Story of Lao r: Filling in the Gaps. 97-109 GARRY W. DAVIS Lao Khrang and Luang Phrabang Lao: A Comparison of Tonal Systems and 110-143 Foreign-Accent Rating by Luang Phrabang Judges. VARISA OSATANANDA Phuan in Banteay Meancheay Province, Cambodia: Resettlement under the 144-166 Reign of King Rama III of Siam THANANAN TRONGDEE The Journal of Lao Studies is published twice per year by the Center for Lao Studies, 65 Ninth Street, San Francisco, CA, 94103, USA. For more information, see the CLS website at www.laostudies.org. Please direct inquiries to [email protected]. ISSN : 2159-2152 Books for review should be sent to: Justin McDaniel, JLS Editor 223 Claudia Cohen Hall 249 S. 36th Street University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104 Copying and Permissions Notice: This journal provides open access to content contained in every issue except the current issue, which is open to members of the Center for Lao Studies. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement October 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 44 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 48 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 49 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 56 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 60 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 October 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Dress and Identity Among the Black Tai of Loei Province, Thailand

DRESS AND IDENTITY AMONG THE BLACK TAI OF LOEI PROVINCE, THAILAND Franco Amantea Bachelor of Arts, Simon Fraser University 2003 THESIS SUBMITTED 1N PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Sociology and Anthropology O Franco Amantea 2007 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY 2007 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Franco Amantea Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: Dress and Identity Among the Black Tai of Loei Province, Thailand Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Gerardo Otero Professor of Sociology Dr. Michael Howard Senior Supervisor Professor of Anthropology Dr. Marilyn Gates Supervisor Associate Professor of Anthropology Dr. Brian Hayden External Examiner Professor of Archaeology Date Defended: July 25,2007 Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the "Institutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

20180613113049 4678.Pdf

CHINA FOUNDATION FOR POVERTY ALLEVIATION ANNUAL REPORT Focus on the Extreme Poor Assist to Realize National Strategy ABOUT US China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation, established in 1989, is a national public foundation registered with the Ministry of Civil Affairs. It was awarded with the National 5A Foundation by the Ministry of Civil Affairs in 2007 and 2013. It was first identi ed by the Ministry of Civil A airs as a charitable organization with public fund- raising quali cation in September 2016. OUR VISION Be the best trusted, the best expected and the best respected international philanthropy platform OUR MISSION Disseminate good and reduce poverty, help others to achieve their aims, and make the good more powerful OUR VALUES Service, Innovation, Transparency, Tenacity On December 4, The 4th World Internet Conference “Shared Dividends: Targeted Poverty Alleviation through the Internet” hosted by China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation was held in Wuzhen. Liu Yongfu, Director of the State Council Leading Group Offi ce of Poverty Alleviation and Development, attended the forum and made an important speech. CHINA FOUNDATION FOR POVERTY ALLEVIATION ANNUAL REPORT By the end of 2017 CFPA had accumulatively raised poverty alleviation funds and materials of RMB 34.09 billion yuan Number of benefi ciaries in the impoverished condition and the disaster areas reached 33,280,700 person-time Zheng Wenkai, President of China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation The year of 2017 was a milestone year for the development of the socialism with Chinese characteristics. The 19th National Party Congress was successfully held and China has entered a new era and embarked on a new journey with a new attitude. -

Bandits and the State Unresolved Disputes in Southeast Asia

The Newsletter | No.78 | Autumn 2017 24 | The Review Bandits and the State If clothes make the man then we can say that the clothes of bandits came in all shapes and sizes. There was no such thing as the typical bandit, no one size fits all. Some bandits neatly fit Eric Hobsbawm’s formula for social bandits who robbed the rich and gave to the poor and who lived among and protected peasant communities. Others, and probably most, simply looked out for themselves, plundering both rich and poor. Some bandits were career professionals, but most were simply amateurs who took up banditry as a part-time job to supplement meagre legitimate earnings. While some bandits formed large permanent gangs, even armies numbering into the thousands, other gangs were ad hoc and small, usually only numbering in the tens or twenties. Most small gangs disbanded after a few heists. Many of the larger, more permanent gangs tended to operate in remote areas far away from the seats of government, but some gangs, usually the smaller impermanent ones, also operated in densely populated core areas. Although some bandits had political ambitions and received recognition and legitimacy from the state, most simply remained thugs and criminals throughout their careers. None of these categories, however, were mutually exclusive, as roles – like clothes – often changed according to circumstances. Reviewer: Robert Antony, Guangzhou University Reviewed title: who hailed from south China’s Qinzhou area in what is never became imperial bandits, but instead remained Bradley Camp Davis. 2017 now Guangxi province. A charismatic figure and skilful outlaws and wanted criminals. -

Bigger Brics, Larger Role

ISSUE 3 · 2017 《中国人大》对外版 National People’s Congress of China BIGGER BRICS, LARGER ROLE IN ITs sEcOND DEcADE, BRICS Is READY FOR A GREATER sHARE IN GLObAL GOVERNANcE President Xi Jinping (C) and other leaders of BRICS countries pose for a group photo during the 2017 President Xi Jinping presides over the BRICS Summit in Xiamen, south- Ninth BRICS Summit in Xiamen, Fujian east China’s Fujian Province, on Province, September 4. South African September 4. Zhang Duo President Jacob Zuma, Brazilian President Michel Temer, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Xiamen International Conference Modi attended the summit. Xie Huanchi and Exhibition Center VCG President Xi Jinping meets the press at the end of the Ninth BRICS Summit in Xiamen, Fujian Province, September 5. Hou Yu SPECIAL REPORT 6 Bigger BRICS, larger role Contents BRICS Summit Special Report 6 22 Bigger BRICS, larger role Zhang Dejiang visits Portugal, Poland and Serbia HK’s 20th Return Anniversary 26 Time-honored friendship 12 heralds future-oriented partnership President Xi Jinping’s speech at Focus the meeting celebrating the 20th anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to the motherland and the inau- 30 gural ceremony of the fifth-term China’s comprehensive moves HKSAR government in advancing rule of law 16 32 The tale of a city Laudable progress in advancing rule of law 4 NATIONAL PEOPLE’S CONGRESS OF CHINA NPC The tale of a city 16 43 China’s comprehensive moves On the wings of modernization 30 in advancing rule of law ISSUE 3 · 2017 Supervision Nationality -

Taiwán: De Provincia China a Colonia

Revista mexicana de estudios sobre la Cuenca del Pacífico Tercera Época • Volumen3 • Número 5 • Enero / Junio 200 9 • Colima, México Revista mexicana de estudios sobre la Cuenca del Pacífico Tercera Época • Volumen3 • Número5 • Enero/ Juniode 200 9 • Colima, México Dr. Fernando Alfonso Rivas Mira Comité editorial nacional Coordinador de la revista Dra . Mayrén Polanco Gaytán / Universidad de Colima, Lic. Ihovan Pineda Lara Facultad de Economía Asistente de coordinación de la revista Mt or. Alfredo Romero Castilla / UNAM, Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales Comité editorial internacional Dr. Juan González García / Universidad de Colima, CUEICP Dr. José Ernesto Rangel Delgado / Universidad de Colima Dr. Hadi Soesastro ( ) Dr. Pablo Wong González / Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo, CIAD Sonora Center for Strategic and International Studies, Dr. Clemente Ruiz Durán / UNAM-Facultad de Economía Indonesia Dr. León Bendesky Bronstein / ERI Dr. Víctor López Villafañe / ITESM-Relaciones Dr. Pablo Bustelo Gómez Internacionales, Monterrey Universidad Complutense de Madrid, España Dr. Carlos Uscanga Prieto / UNAM-Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales Dr. Kim Won ho Profr. Omar Martínez Legorreta / Colegio Mexiquense Universidad Hankuk, Corea del Sur Dr. Ernesto Henry Turner Barragán / UAM-Azcapotzalco Departamento de Economía Dr. Mitsuhiro Kagami Dra. Marisela Connelly / El Colegio de México-Centro de Instituto de Economías en Desarrollo, Japón Estudios de Asia y África Universidad de Colima Cuerpo de árbitros Dra. Genevieve Marchini W. / Universidad de Guadalajara- MC Miguel Ángel Aguayo López Departamento de Estudios Internacionales. Especializada en Rector Economía Financiera en la región del Asia Pacífico Mtro. Alfonso Mercado García / El Colegio de México y El Dr. Ramón Cedillo Nakay Colegio de la Frontera Norte.