Is This Pa Chay Vue? a Study in Three Frames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory Pictures in a Time of Defeat: Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory pictures in a time of defeat: depicting war in the print and visual culture of late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/18449 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. VICTORY PICTURES IN A TIME OF DEFEAT Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884-1901 Yin Hwang Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the History of Art 2014 Department of the History of Art and Archaeology School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 2 Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. -

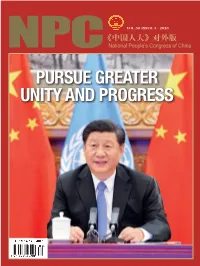

Pursue Greater Unity and Progress News Brief

VOL.50 ISSUE 3 · 2020 《中国人大》对外版 NPC National People’s Congress of China PURSUE GREATER UNITY AND pROGRESS NEWS BRIEF President Xi Jinping attends a video conference with United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres from Beijing on September 23. Liu Weibing 2 NATIONAL PEOPle’s CoNGRESS OF CHINA ISSUE 3 · 2020 3 6 Pursue greater unity and progress Contents UN’s 75th Anniversary CIFTIS: Global Services, Shared Prosperity National Medals and Honorary Titles 6 18 26 Pursue greater unity Global services, shared prosperity President Xi presents medals and progress to COVID-19 fighters 22 9 Shared progress and mutually Special Reports Make the world a better place beneficial cooperation for everyone 24 30 12 Accelerated development of trade in Work together to defeat COVID-19 Xi Jinping meets with UN services benefits the global economy and build a community with a shared Secretary-General António future for mankind Guterres 32 14 Promote peace and development China’s commitment to through parliamentary diplomacy multilateralism illustrated 4 NATIONAL PEOPle’s CoNGRESS OF CHINA 42 The final stretch Accelerated development of trade in 24 services benefits the global economy 36 Top legislator stresses soil protection ISSUE 3 · 2020 Fcous 38 Stop food waste with legislation, 34 crack down on eating shows Top legislature resolves HKSAR Leg- VOL.50 ISSUE 3 September 2020 Co vacancy concern Administrated by General Office of the Standing Poverty Alleviation Committee of National People’s Congress 36 Top legislator stresses soil protection Chief Editor: Wang Yang General Editorial 42 Office Address: 23 Xijiaominxiang, The final stretch Xicheng District, Beijing 37 100805, P.R.China Full implementation wildlife protection Tel: (86-10)5560-4181 law stressed (86-10)6309-8540 E-mail: [email protected] COVER: President Xi Jinping ad- ISSN 1674-3008 dresses a high-level meeting to CN 11-5683/D commemorate the 75th anniversary Price: RMB 35 of the United Nations via video link Edited by The People’s Congresses Journal on September 21. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement October 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 44 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 48 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 49 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 56 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 60 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 October 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

20180613113049 4678.Pdf

CHINA FOUNDATION FOR POVERTY ALLEVIATION ANNUAL REPORT Focus on the Extreme Poor Assist to Realize National Strategy ABOUT US China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation, established in 1989, is a national public foundation registered with the Ministry of Civil Affairs. It was awarded with the National 5A Foundation by the Ministry of Civil Affairs in 2007 and 2013. It was first identi ed by the Ministry of Civil A airs as a charitable organization with public fund- raising quali cation in September 2016. OUR VISION Be the best trusted, the best expected and the best respected international philanthropy platform OUR MISSION Disseminate good and reduce poverty, help others to achieve their aims, and make the good more powerful OUR VALUES Service, Innovation, Transparency, Tenacity On December 4, The 4th World Internet Conference “Shared Dividends: Targeted Poverty Alleviation through the Internet” hosted by China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation was held in Wuzhen. Liu Yongfu, Director of the State Council Leading Group Offi ce of Poverty Alleviation and Development, attended the forum and made an important speech. CHINA FOUNDATION FOR POVERTY ALLEVIATION ANNUAL REPORT By the end of 2017 CFPA had accumulatively raised poverty alleviation funds and materials of RMB 34.09 billion yuan Number of benefi ciaries in the impoverished condition and the disaster areas reached 33,280,700 person-time Zheng Wenkai, President of China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation The year of 2017 was a milestone year for the development of the socialism with Chinese characteristics. The 19th National Party Congress was successfully held and China has entered a new era and embarked on a new journey with a new attitude. -

Bandits and the State Unresolved Disputes in Southeast Asia

The Newsletter | No.78 | Autumn 2017 24 | The Review Bandits and the State If clothes make the man then we can say that the clothes of bandits came in all shapes and sizes. There was no such thing as the typical bandit, no one size fits all. Some bandits neatly fit Eric Hobsbawm’s formula for social bandits who robbed the rich and gave to the poor and who lived among and protected peasant communities. Others, and probably most, simply looked out for themselves, plundering both rich and poor. Some bandits were career professionals, but most were simply amateurs who took up banditry as a part-time job to supplement meagre legitimate earnings. While some bandits formed large permanent gangs, even armies numbering into the thousands, other gangs were ad hoc and small, usually only numbering in the tens or twenties. Most small gangs disbanded after a few heists. Many of the larger, more permanent gangs tended to operate in remote areas far away from the seats of government, but some gangs, usually the smaller impermanent ones, also operated in densely populated core areas. Although some bandits had political ambitions and received recognition and legitimacy from the state, most simply remained thugs and criminals throughout their careers. None of these categories, however, were mutually exclusive, as roles – like clothes – often changed according to circumstances. Reviewer: Robert Antony, Guangzhou University Reviewed title: who hailed from south China’s Qinzhou area in what is never became imperial bandits, but instead remained Bradley Camp Davis. 2017 now Guangxi province. A charismatic figure and skilful outlaws and wanted criminals. -

Bigger Brics, Larger Role

ISSUE 3 · 2017 《中国人大》对外版 National People’s Congress of China BIGGER BRICS, LARGER ROLE IN ITs sEcOND DEcADE, BRICS Is READY FOR A GREATER sHARE IN GLObAL GOVERNANcE President Xi Jinping (C) and other leaders of BRICS countries pose for a group photo during the 2017 President Xi Jinping presides over the BRICS Summit in Xiamen, south- Ninth BRICS Summit in Xiamen, Fujian east China’s Fujian Province, on Province, September 4. South African September 4. Zhang Duo President Jacob Zuma, Brazilian President Michel Temer, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Xiamen International Conference Modi attended the summit. Xie Huanchi and Exhibition Center VCG President Xi Jinping meets the press at the end of the Ninth BRICS Summit in Xiamen, Fujian Province, September 5. Hou Yu SPECIAL REPORT 6 Bigger BRICS, larger role Contents BRICS Summit Special Report 6 22 Bigger BRICS, larger role Zhang Dejiang visits Portugal, Poland and Serbia HK’s 20th Return Anniversary 26 Time-honored friendship 12 heralds future-oriented partnership President Xi Jinping’s speech at Focus the meeting celebrating the 20th anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to the motherland and the inau- 30 gural ceremony of the fifth-term China’s comprehensive moves HKSAR government in advancing rule of law 16 32 The tale of a city Laudable progress in advancing rule of law 4 NATIONAL PEOPLE’S CONGRESS OF CHINA NPC The tale of a city 16 43 China’s comprehensive moves On the wings of modernization 30 in advancing rule of law ISSUE 3 · 2017 Supervision Nationality -

Taiwán: De Provincia China a Colonia

Revista mexicana de estudios sobre la Cuenca del Pacífico Tercera Época • Volumen3 • Número 5 • Enero / Junio 200 9 • Colima, México Revista mexicana de estudios sobre la Cuenca del Pacífico Tercera Época • Volumen3 • Número5 • Enero/ Juniode 200 9 • Colima, México Dr. Fernando Alfonso Rivas Mira Comité editorial nacional Coordinador de la revista Dra . Mayrén Polanco Gaytán / Universidad de Colima, Lic. Ihovan Pineda Lara Facultad de Economía Asistente de coordinación de la revista Mt or. Alfredo Romero Castilla / UNAM, Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales Comité editorial internacional Dr. Juan González García / Universidad de Colima, CUEICP Dr. José Ernesto Rangel Delgado / Universidad de Colima Dr. Hadi Soesastro ( ) Dr. Pablo Wong González / Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo, CIAD Sonora Center for Strategic and International Studies, Dr. Clemente Ruiz Durán / UNAM-Facultad de Economía Indonesia Dr. León Bendesky Bronstein / ERI Dr. Víctor López Villafañe / ITESM-Relaciones Dr. Pablo Bustelo Gómez Internacionales, Monterrey Universidad Complutense de Madrid, España Dr. Carlos Uscanga Prieto / UNAM-Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales Dr. Kim Won ho Profr. Omar Martínez Legorreta / Colegio Mexiquense Universidad Hankuk, Corea del Sur Dr. Ernesto Henry Turner Barragán / UAM-Azcapotzalco Departamento de Economía Dr. Mitsuhiro Kagami Dra. Marisela Connelly / El Colegio de México-Centro de Instituto de Economías en Desarrollo, Japón Estudios de Asia y África Universidad de Colima Cuerpo de árbitros Dra. Genevieve Marchini W. / Universidad de Guadalajara- MC Miguel Ángel Aguayo López Departamento de Estudios Internacionales. Especializada en Rector Economía Financiera en la región del Asia Pacífico Mtro. Alfonso Mercado García / El Colegio de México y El Dr. Ramón Cedillo Nakay Colegio de la Frontera Norte. -

Musical Taiwan Under Japanese Colonial Rule: a Historical and Ethnomusicological Interpretation

MUSICAL TAIWAN UNDER JAPANESE COLONIAL RULE: A HISTORICAL AND ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION by Hui‐Hsuan Chao A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in The University of Michigan 2009 Doctoral Committee: Professor Joseph S. C. Lam, Chair Professor Judith O. Becker Professor Jennifer E. Robertson Associate Professor Amy K. Stillman © Hui‐Hsuan Chao 2009 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Throughout my years as a graduate student at the University of Michigan, I have been grateful to have the support of professors, colleagues, friends, and family. My committee chair and mentor, Professor Joseph S. C. Lam, generously offered his time, advice, encouragement, insightful comments and constructive criticism to shepherd me through each phase of this project. I am indebted to my dissertation committee, Professors Judith Becker, Jennifer Robertson, and Amy Ku’uleialoha Stillman, who have provided me invaluable encouragement and continual inspiration through their scholarly integrity and intellectual curiosity. I must acknowledge special gratitude to Professor Emeritus Richard Crawford, whose vast knowledge in American music and unparallel scholarship in American music historiography opened my ears and inspired me to explore similar issues in my area of interest. The inquiry led to the beginning of this dissertation project. Special thanks go to friends at AABS and LBA, who have tirelessly provided precious opportunities that helped me to learn how to maintain balance and wellness in life. ii Many individuals and institutions came to my aid during the years of this project. I am fortunate to have the friendship and mentorship from Professor Nancy Guy of University of California, San Diego. -

Markets in the Mountains: Upland Trade-Scapes, Trader Livelihoods, and State Development Agendas in Northern Vietnam

MARKETS IN THE MOUNTAINS: UPLAND TRADE-SCAPES, TRADER LIVELIHOODS, AND STATE DEVELOPMENT AGENDAS IN NORTHERN VIETNAM Christine Bonnin Department of Geography McGill University, Montréal Submitted October 2011 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Christine Bonnin 2011 In loving memory of a dear friend, Radoslaw Stypczynski (Radek) and for his Sa Pa Sisters ii ABSTRACT In this dissertation I investigate market formation and integration in the northern uplands of Vietnam (Lào Cai province) through a focus on the everyday processes by which markets are created and (re)shaped at the confluence of local innovation and initiatives, state actions, and wider market forces. Against a historically-informed backdrop of the ‘local’ research context with regard to ethnicity, cultural practice, livelihoods, markets and trade, I situate and critique the broader Vietnam state agenda. At present, the state supports regularising market development often in accordance with a lowland majority model, and promoting particular aspects of tourism that at times mesh, while at others clash, with upland subsistence needs, customary practice, and with uplanders successfully realising new opportunities. State-led initiatives to foster market integration are often instituted without informed consideration of their effects on the specific nature and complexity of upland trade, such as for the realisation of materially and culturally viable livelihoods. Conceptually, I weave together a framework for the study that draws key elements from three main strands of scholarship: 1) actor-oriented approaches to livelihoods; 2) social embeddedness, social network and social capital approaches to market trade and exchange, and; 3) the commodity-oriented literature. -

French Missionary Expansion in Colonial Upper Tonkin

287 Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 35 (2), pp 287–310 June 2004. Printed in the United Kingdom. © 2004 The National University of Singapore DOI: 10.1017/S0022463404000153 French Missionary Expansion in Colonial Upper Tonkin Jean Michaud This article examines the circumstances and logic of French Catholic missionary expansion in Upper Tonkin. It explores how, over a few decades, the missionary push in the mountainous outskirts of the Red River Delta was conceived, how it unfolded, and how it came to a standstill in the 1920s before its decline towards the final exit of the French in the late 1940s. The age of the uncompromising antipathy between a number of academic anthro- pologists and missionaries is over. With many authors making a case for acknowledging the contribution of non-academic ethnographers to the discipline of anthropology, examination of missionaries’ work as part of the wider category of non-professional ethnographers has become critical for the discipline.1 Is it not true that historically anthropologists have made great use of missionary writings – though perhaps more privately than publicly? Peter Pels has noted, for instance, that ‘before the advent of the professional fieldworker [in the first decade of the twentieth century], British anthro- pologists mainly used data collected by government officials and missionaries, while a segment of the missionary movement drew on ethnology as a tool in developing missionary methods’.2 This observation emphasises even more the contested boundaries between the two worlds. Colonial missionary ethnography was for the most part conducted by nonspecialists for whom this activity was accidental, performed in the course of their apostolic mission. -

1 INTRODUCTION Accounts of Taiwan and Its History Have Been

INTRODUCTION Accounts of Taiwan and its history have been profoundly influenced by cultural and political ideologies, which have fluctuated radically over the past four centuries on the island. Small parts of Taiwan were ruled by the Dutch (1624-1662), Spanish (1626-1642), Zheng Chenggong (Koxinga)1 and his heirs (1662-1683), and a large part by Qing Dynasty China (1683-1895). Thereafter, the whole of the island was under Japanese control for half a century (1895-1945), and after World War II, it was taken over by the Republic of China (ROC), being governed for more than four decades by the authoritarian government of Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang (KMT), or Chinese Nationalist Party,2 before democratization began in earnest in the late 1980s. Taiwan’s convoluted history and current troubled relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which claims Taiwan is “a renegade province” of the PRC, has complicated the world’s understanding of Taiwan. Many Western studies of Taiwan, primarily concerning its politics and economic development, have been conducted as an 1 Pinyin is employed in this dissertation as its Mandarin romanization system, though there are exceptions for names of places which have been officially transliterated differently, and for names of people who have been known to Western scholarship in different forms of romanization. In these cases, the more popular forms are used. All Chinese names are presented in the same order as they would appear in Chinese, surname first, given name last, unless the work is published in English, in which case the surname appears last. -

Francoska Tujska Legija V 19. Stoletju

UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŽBENE VEDE Petra Žabkar Francoska Tujska legija v 19. stoletju - primer enote za posebne namene? Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2010 UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŽBENE VEDE Petra Žabkar Mentor: doc. dr. Damijan Guštin Francoska Tujska legija v 19. stoletju - primer enote za posebne namene? Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2010 Francoska Tujska legija v 19. stoletju - primer enote za posebne namene? Francoska Tujska legija je najemniška vojaška organizacija, ki je nastala s kraljevim odlokom leta 1831. Njene naloge so bile širjenje in ohranjanje francoskega kolonialnega imperija, namenjena je bila zlasti za izvajane nalog za katere vojaški obvezniki ne bi bili ustrezni. Sestavljali so jo tuji rekruti in namenjena je bila izključno delovanju v tujini. Njen dom je postala Alžirija. V 19. stoletju je delovala v Afriki, Evropi, Severni Ameriki, Aziji in na Madagaskarju. Velik pomen je v nasprotju z načeli vojskovanja v Evropi v Legiji pridobila mobilnost enot ter sposobnost presenečenja. V francoski Tujski legiji je nastala tradicija dolgih pohodov, ki je pomembno vplivala na razvoj esprit de corps in izboljšanje odnosov med vojaki in častniki. Legija sčasoma prične sloveti kot enota, ki se bojuje do konca, kot primerno mesto za hitro vojaško kariero, ki pritegne tudi najboljši kader. Diplomsko delo obravnava francosko Tujsko legijo in njen nastanek, lastnosti ter odnos do francoske vojske. Namen dela je pojasniti motive za njen nastanek ter ugotoviti, če je že ob svojem nastanku ali pa pozneje v 19. stoletju razvila lastnosti enot za posebne namene. Poleg tega je raziskan njen odnos do Francoske vojske. KLJUČNE BESEDE: francoska Tujska legija, francoski kolonialni imperij, Alžirija, 19.