The Character of the Fairy Tale Devil in the Graphics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level)

University Of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level) Autumn semester 2014/15 [01.09.2014 – 21.12.2014] A HISTORY OF LATVIAN CULTURE on Tuesdays, (2 credits*) Wednesdays from 02.09.14 till 24.09.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst2102 Azpazijas Bvld. 5 lect. I. Runce Room 120 LATVIAN FOLKLORE AND LITERATURE on Thursdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. 5 from 04.09.14 till 23.10.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: Folk4012 Room 120 dr. R. Auškāps INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF DIPLOMACY (1648-1918) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 10:30 – 12:00 Code: Vēst2350 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga THE HISTORY OF BALTIC (1200 till 1850-60) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd.19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 14:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst1067 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga MUSIC IN THE BALTICS on Tuesdays (2 credits*) Visvalža Str. 4a from 21.10.14 till 16.12.14 10:30. – 14:00 Code : MākZ1031 Room 305 Prof. V. Muktupāvels INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARTS IN THE BALTIC STATES on Wednesdays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 29.10.14 till 17.12.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: JurZ2024 Room 6 Asoc.prof. A. Kučs RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT on Thursdays OF LATVIA Azpazijas Bvld. 5 (2 credits*) Room 320 from 06.11.14 till 18.12.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Ekon5069 Prof. B. Sloka Room 518 + Monday, 10.11.14 A HISTORY OF ETHNIC MINORITIES on Mondays, from 01.12.14 till 16.12.14 14:30 – 18:00 IN LATVIA Tuesdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. -

Between National and Academic Agendas Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940

BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Other titles in the same series Södertörn Studies in History Git Claesson Pipping & Tom Olsson, Dyrkan och spektakel: Selma Lagerlöfs framträdanden i offentligheten i Sverige 1909 och Finland 1912, 2010. Heiko Droste (ed.), Connecting the Baltic Area: The Swedish Postal System in the Seventeenth Century, 2011. Susanna Sjödin Lindenskoug, Manlighetens bortre gräns: tidelagsrättegångar i Livland åren 1685–1709, 2011. Anna Rosengren, Åldrandet och språket: En språkhistorisk analys av hög ålder och åldrande i Sverige cirka 1875–1975, 2011. Steffen Werther, SS-Vision und Grenzland-Realität: Vom Umgang dänischer und „volksdeutscher” Nationalsozialisten in Sønderjylland mit der „großgermanischen“ Ideologie der SS, 2012. Södertörn Academic Studies Leif Dahlberg och Hans Ruin (red.), Fenomenologi, teknik och medialitet, 2012. Samuel Edquist, I Ruriks fotspår: Om forntida svenska österledsfärder i modern historieskrivning, 2012. Jonna Bornemark (ed.), Phenomenology of Eros, 2012. Jonna Bornemark och Hans Ruin (eds), Ambiguity of the Sacred, 2012. Håkan Nilsson (ed.), Placing Art in the Public Realm, 2012. Lars Kleberg and Aleksei Semenenko (eds), Aksenov and the Environs/Aksenov i okrestnosti, 2012. BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Södertörns högskola Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image, taken from Latvijas Universitāte Illūstrācijās, p. 10. Gulbis, Riga, 1929. Cover: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson and Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Studies in History 13 ISSN 1653-2147 Södertörn Academic Studies 51 ISSN 1650-6162 ISBN 978-91-86069-52-0 Contents Foreword ...................................................................................................................................... -

Couronians | Semigallians | Selonians

BALTS’ ROAD, THE COURONIAN ROUTE SEGMENT Route: Rucava – Liepāja – Grobiņa – Jūrkalne – Alsunga – Kuldīga – Ventspils – Talsi – Valdemārpils – Sabile – Saldus – Embūte – Mosėdis – Plateliai – Kretinga – Klaipėda – Palanga – Rucava Duration: 3–4 days. Length about 790 km In ancient times, Couronians lived on the coast of the Baltic Sea. At that time, the sea and rivers were an important waterway that inuenced their way of life and interaction with neighbouring nations. You will nd out about this by taking the circular Couronian Route Segment. Peaceful deals were made during trading. Merchants from faraway lands Macaitis, Tērvete Tourism Information Centre, Zemgale Planning Region. Planning Zemgale Centre, Information Tourism Tērvete Macaitis, were tempted to visit the shores of the Baltic Sea looking for the northern gold – Photos: Līva Dāvidsone, Artis Gustovskis, Arvydas Gurkšnis, Denisas Nikitenka, Mindaugas Mindaugas Nikitenka, Denisas Gurkšnis, Arvydas Gustovskis, Artis Dāvidsone, Līva Photos: Publisher: Kurzeme Planning Region, Zemgale Planning Region 2019 Region Planning Zemgale Region, Planning Kurzeme Publisher: amber. To nd out more about amber, visit the Palanga Amber Museum (40) Centre, National Regional Development Agency in Lithuania. in Agency Development Regional National Centre, and the Liepāja Crafts House (6). Ancient Couronian boats, the barges, are Authors: Kurzeme Planning Region, Zemgale Planning Region, Šiauliai Tourism Information Information Tourism Šiauliai Region, Planning Zemgale Region, Planning Kurzeme Authors: -

Latvijas Universitāte Austra Celmiņa-Ķeirāne

LATVIJAS UNIVERSITĀTE AUSTRA CELMIŅA-ĶEIRĀNE LATVIEŠU MITOLOĢIJA VIZUĀLĀ UN VERBĀLĀ TEKSTĀ (1880–1945) PROMOCIJAS DARBS Doktora grāda iegūšanai folkloristikā Apakšnozare: mitoloģija Darba zinātniskā vadītāja: Dr. habil. philol., LU prof. Janīna Kursīte-Pakule Rīga, 2019 SATURS IEVADS.............................................................................................................................. 3 1. TEKSTS, TĀ UZBŪVE UN KONTEKSTS............................................................. 20 1.1. Folkloras teksts kontekstuālās pieejas skatījumā............................................. 20 1.2. Mākslinieciska teksta definīcija......................................................................... 22 1.3. Strukturālās uzbūves elementi un principi vizuālā un verbālā tekstā........... 25 1.3.1. Mākslas darba siţets...................................................................................... 25 1.3.2. Laiktelpa mākslinieciska teksta kompozīcijā................................................ 29 1.3.3. Krāsa un tās simboliskā vērtība..................................................................... 38 1.3.4. Izteiksmes būtība........................................................................................... 44 1.4. Diskursu pārklāšanās mitoloģiskās tēmas kontekstā....................................... 45 Secinājumi........................................................................................................................ 46 2. MITOLOĢISKĀS TĒMAS ATTĪSTĪBA VIZUĀLĀ TEKSTĀ. LATVIJAS KULTŪRVĒSTURISKAIS -

Dress Code: Latvian

Dress Code: Latvian 1 Cover photo: National dress is an integral part of Latvia’s heritage. If you have ever looked at one, you must have noticed Contemporary remake that more attention was paid to beauty than practicality. The many colourful layers, ornaments, brooches of a Rucava region folk and embroideries probably did not make life easier for Latvians of the past. Yet even today, when you spot dress made out of 9 belts, someone in such a costume, you will sense the elegance and grace radiating from both the wearer and 4 trousers, 3 crocheted garments. blankets, a jacket, shirt, sweater and a bicycle Of course, garments that have survived up to the present are costumes worn on festive occasions. They gearwheel. Recycled.lv have been handed down from generation to generation as treasured heirlooms. Nowadays, you are most collection Etnography, likely to come across people dressed in these timeless jewels during the Nationwide Song and Dance cel- 2014. ebration. All participants of choirs and dance ensembles are likely to wear costumes from their respective region of ancestry. Upper right: Contemporary At its essence, a traditional Latvian costume was the dress worn by the indigenous inhabitants of Latvia – accessories with the Balts and Livs. It includes everything that its owner hand-made for the various seasons and occasions. traditional Latvian graphic In contemporary Latvia, artists and designers still draw inspiration from the countless ornaments, symbols, symbols. Each sign has colour combinations and designs, the knowledge of which has been kept alive throughout the centuries. its own meaning and was The oldest models date back to as early as the 13th century. -

3 Phd Student Latvian Academy of Culture Ludzas Iela 24, Rīga, Lv-1003

WRestlinG ON THE TABle: THE COntemPORARY WEDDinG MEAL in LAtviA AstrA spAlvēnA PhD student Latvian Academy of Culture ludzas iela 24, rīga, LV-1003 e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT the object of this paper is to examine the contemporary wedding meal in latvia, focusing on one particular social group of well situated young couples who choose fine dining restaurants or rented venues for their wedding celebrations because they considered restaurant weddings more elaborate and modern. the desire to embrace a modern lifestyle is the way in which to obtain a new identity in a rapidly changing post-socialist world. the aim of present research is to reveal how different traditions intertwine in the wedding meal – new or borrowed, with ancient and national or soviet tradi- tions. While followers of a modern lifestyle are emphasising a challenge to tradi- tions, it is nevertheless the wedding meal and symbolic practices connected with it that indicates a more or less intentional respect for tradition. I argue that the wedding ceremony reveals the shift from rites of passage to social distinction. this argument is developed by analysing how social and family relationships, value systems and the ethos as a whole have changed recently in latvia. the use of the symbolic capacity of wedding food, denoting fertility and prosperity, provides the stability of the structure of the wedding feast, which also affects the structure of the marriage ceremony as a whole. KEYWORDS: wedding rituals • contemporary traditions • festive meal • food as symbol INTRODUCTION the metaphor of wrestling is applied here to the wedding meal to highlight some of its essential features. -

Socialist Folkloristics: a Disciplinary Heritage

Institute of Literature, Folklore and Art, University of Latvia SOCIALIST FOLKLORISTICS: A DISCIPLINARY HERITAGE International Interdisciplinary Conference Riga, 16–18 December 2020 via the Zoom platform UDK 7/9(062) So084 The conference is organized by the Institute of Literature, Folklore and Art of the University of Latvia Organizing Committee: Toms Ķencis Rita Grīnvalde Baiba Krogzeme-Mosgorda Gatis Ozoliņš Ginta Pērle-Sīle Digne Ūdre Māra Vīksna Editors: Baiba Krogzeme-Mosgorda, Rita Grīnvalde Language editor: Laine Kristberga Cover designer: Krišs Salmanis Layout designer: Baiba Dūdiņa Cover photo: State Archives of Latvia (LVA 1757. f, 5-vp apr., 45. l., 64. lp.) The conference is funded by the Latvian Council of Science project Latvian Folkloristics (1945–1985) (grant No. lzp-2018/2-0268) ISBN 978-9984-893-49-5 © Institute of Literature, Folklore and Art of the University of Latvia, 2020 © Authors, 2020 The Mission Statement The grandiose Soviet experiment left us a heritage that profoundly affects the public image, collections, and research of folk-related disciplines even today. It manifests itself in a broad range of representations from stage performances and archival collections to the very perception of what is authentic, real, or national. Socialist traditions were invented, myths made, and rituals staged. And now, it is a vast and crudely mapped history of culture and knowledge production, stretching for more than 70 years across half of Europe and beyond. The conference Socialist Folkloristics: A Disciplinary Heritage aims to produce and exchange knowledge that will help to arrive at better understanding of this region – beyond the outdated Cold War epistemic dispositif and across the boundaries of national scholarships. -

Latvian Medieval Symbols

“GREAT ROUTES IN Latvian medieval THE MIDDLE AGE AND THEIR SYMBOLOGY” Nr. 2016-1-ES01- symbols KA219-025035_3 Katrīna Kārkle and Dace Asme Latvia Christianity symbols in Latvia middle age time The Livonian Brothers of the Sword (Latin: Fratres militiæ Christi Livoniae, German: Schwertbrüderorden, French: Ordre des Chevaliers Porte-Glaive) was a catholic military order established by the third bishop of Riga, Bishop Albert of Riga (or possibly Theoderich von Treyden), in 1202.Religious organization of German knights in the territory of Latvia and Estonia. The suit is a white cape with a red cross on it. Sword- power Cross- Christianity White – holy,innocence Map of the Livonian order The Livonian Order, or the Holy House of the Holy Family of Jerusalem of Saint Mary, the brotherhood of Livonia (Latin: Fratres de Domo Sanctae Mariae Theutonicorum, Jerusalemitana per Livonia) was the branch of the German Order in Livonia, which was formed after the destruction of the Order of the Swordsman in the Sun Battle of 1236. Terra Mariana – land of St.Mary – Holy Jesus Christ mother Seal of the Livonian Order's master and the Coat of Arms of Teutonic Knights in the Livonian Order Knight of the Livonian Order on a horse The Livonian Order was an autonomous branch of the Teutonic Order, formed in 1237. It was later a member of the Livonian Confederation, from 1435 to 1561. The key is the symbol of success Tower – symbolizing power, as well as taking off above a daily life. Riga town oldest stamp. 1226. Since the first half of the 16th century, at the back of the Riga bench at Lübeck Shipyard, the first emblem of Riga has been preserved in heraldic colors: two towers with open gates on the silver field, a red cross on the top, two black crossed keys below it (bench copy RVMM) Claw cross Church Latvian Ethnographic Open-Air Museum. -

Art and Artist

International Journal of Culture and History, Vol. 3, No. 3, September 2017 Representing Time: Art and Artist Mg.art. Agita Gritane means to live and work in the changing conditions of political Abstract—The proposed paper for the Conference is the power. insight into Latvian artist Jekabs Bine (1895-1955) life and Each political power regime in the history of art brings its creative work during 20th century first half. Jekabs Bine was position reflection, leaving it as a heritage of the past, which one of the artists of the interwar period who focused on often is synthesized with the next period art direction. In idealized depicting of the Latvian image and search for Latvian identity in the legacy of the past. studies of art and power relations often disappears the human All my research aim is regional identity, going through factor – how at specific circumstances lived and thought the politics, history and art. How changes of political powers during artist – personality that created the art during one or the other the first half of the 20th century affected an artist who strongly power position time and influence. How strong compromise believed in Latvia's identity. I am deeply interested in battle was between external manifestations of creativity and researching what was an artist’s contribution and role in the ideology? making of the Latvian identity? Bine's life and work phenomenon is based on the fact, that the artist dedicated all his life and creative work to find and study the Latvian national identity, in spite of regular political II. -

Latvian Symbols

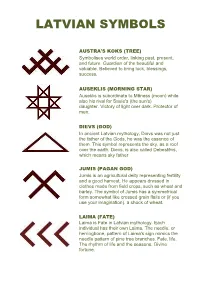

LATVIAN SYMBOLS AUSTRA'S KOKS (TREE) Symbolises world order, linking past, present, and future. Guardian of the beautiful and valuable. Believed to bring luck, blessings, success. AUSEKLIS (MORNING STAR) Auseklis is subordinate to Mēness (moon) while also his rival for Saule's (the sun's) daughter. Victory of light over dark. Protector of men. DIEVS (GOD) In ancient Latvian mythology, Dievs was not just the father of the Gods, he was the essence of them. This symbol represents the sky, as a roof over the earth. Dievs, is also called Debestēvs, which means sky father JUMIS (PAGAN GOD) Jumis is an agricultural deity representing fertility and a good harvest. He appears dressed in clothes made from field crops, such as wheat and barley. The symbol of Jumis has a symmetrical form somewhat like crossed grain flails or (if you use your imagination), a shock of wheat. LAIMA (FATE) Laima is Fate in Latvian mythology. Each individual has their own Laima, The needle, or herringbone, pattern of Laima's sign mimics the needle pattern of pine tree branches. Fate, life. The rhythm of life and the seasons. Divine fortune. MARA (MOTHER EARTH) Māra is the highest divinity of Motherhood. Resolution, completeness. The active, dynamic world. Protector against misfortune, bringer of godliness SAULE (THE SUN) Saulė is one of the most powerful deities, the goddess of life and fertility, warmth and health. She is patroness of the unfortunate, especially orphans. UGUNSKRUSTS (FIRECROSS) Ugunskrusts is a traditional motif from Latvian folklore. It was used as a symbol of its armed forces before the country was occupied by the Soviet Union in 1940. -

History of State and Church Relationships in Latvia

HISTORY OF STATE AND CHURCH RELATIONSHIPS IN LATVIA RINGOLDS BALODIS Separation of Church and State has never implied segregation of reli- gion from society or the complete exclusion of the Church from social life. This would not be possible in a democratic country, as religion and religious associations form one of the main elements structuring society. The official attitude of the traditional Church towards political processes within the state is neutral. However, the Church, which by its nature is a polygamous community, has the power to influence the polit- ical regime within the state, especially due to the fact that it often receives strong external support. Many examples can be quoted in order to sup- port this statement – for example the Holy See, is now seeking to sign a Concordat with the Republic of Latvia. The supporter of the Latvian Orthodox Church is the Orthodox Church of Russia. Its position often concurs with the official government position of Russia. New non-tra- ditional religious organisations come to Latvia only with the help of strong foreign backing. Muslim support is based in Saudi Arabia, the metropolis of Islam Mission, which is even prepared to finance the con- struction of a mosque in Riga. Mormons are supported by the United States. Seventh Day Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses reinforce their status in Latvia with aid from the US and the European Union. If we ignore these links and enforce an imprudent government policy with respect to these Churches, we may face serious foreign policy problems, which in the long run can affect the economy of our country. -

Contemporary Latvian Theatre a Decade Bookazine

Edited by Lauma meLLēna-Bartkeviča Contemporary Latvian Theatre A Decade Bookazine PART OF LatVIAN CENTENARY PROGRAMME The publishing of the bookazine is supported by the Ministry of Culture and State Culture Capital Foundation. Preface ............................................................................................. 5 Lauma mellēna-Bartkeviča In collaboration with: TS THEATRE PROCESSES .................................................. 7 Theatre and Society: Socio-Political Processes and their EN Portrayal in Latvian Theatre of the 21st Century .................... 8 Zane radzobe T New Performance Spaces and Redefinition of the Relationship between Performers and Audience Members in 21st-Century Latvian Theatre: 2010–2020 ..... 24 ON valda čakare, ieva rodiņa idea and concept: Lauma Mellēna-Bartkeviča C editorial board: Valda Čakare (PhD), Lauma Mellēna-Bartkeviča (PhD), Latvian Theatre in the Digital Age .......................................... 36 Ieva Rodiņa (PhD), Guna Zeltiņa (PhD) vēsma Lēvalde reviewers: Ramunė Balevičiūtė (PhD), Anneli Saro (PhD), Newcomers in Latvian Theatre Directing: OF Edīte Tišheizere (PhD) the New Generation and Forms of Theatre-Making .......... 50 ieva rodiņa translators: Inta Ivanovska, Laine Kristberga E Proofreader: Amanda Zaeska Methods of Text Production in Latvian artist: Ieva Upmace Contemporary Theatre............................................................... 62 Photographs: credit by Latvian theatres and personal archives Līga ulberte Theatre Education in Latvia: Traditions and