A Multi-Varied Approach to Meaning of Some East Baltic Neolithic Symbols

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Between West and East People of the Globular Amphora Culture in Eastern Europe: 2950-2350 Bc

BETWEEN WEST AND EAST PEOPLE OF THE GLOBULAR AMPHORA CULTURE IN EASTERN EUROPE: 2950-2350 BC Marzena Szmyt V O L U M E 8 • 2010 BALTIC-PONTIC STUDIES 61-809 Poznań (Poland) Św. Marcin 78 Tel. (061) 8536709 ext. 147, Fax (061) 8533373 EDITOR Aleksander Kośko EDITORIAL COMMITEE Sophia S. Berezanskaya (Kiev), Aleksandra Cofta-Broniewska (Poznań), Mikhail Charniauski (Minsk), Lucyna Domańska (Łódź), Viktor I. Klochko (Kiev), Jan Machnik (Kraków), Valentin V. Otroshchenko (Kiev), Petro Tolochko (Kiev) SECRETARY Marzena Szmyt Second Edition ADAM MICKIEWICZ UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF EASTERN STUDIES INSTITUTE OF PREHISTORY Poznań 2010 ISBN 83-86094-07-9 (print:1999) ISBN 978-83-86094-15-8 (CD-ROM) ISSN 1231-0344 BETWEEN WEST AND EAST PEOPLE OF THE GLOBULAR AMPHORA CULTURE IN EASTERN EUROPE: 2950-2350 BC Marzena Szmyt Translated by John Comber and Piotr T. Żebrowski V O L U M E 8 • 2010 c Copyright by B-PS and Author All rights reserved Cover Design: Eugeniusz Skorwider Linguistic consultation: John Comber Prepared in Poland Computer typeset by PSO Sp. z o.o. w Poznaniu CONTENTS Editor’s Foreword5 Introduction7 I SPACE. Settlement of the Globular Amphora Culture on the Territory of Eastern Europe 16 I.1 Classification of sources . 16 I.2 Characteristics of complexes of Globular Amphora culture traits . 18 I.2.1 Complexes of class I . 18 I.2.2 Complexes of class II . 34 I.3 Range of complexes of Globular Amphora culture traits . 36 I.4 Spatial distinction between complexes of Globular Amphora culture traits. The eastern group and its indicators . 42 I.5 Spatial relations of the eastern and centralGlobular Amphora culture groups . -

Fortified Settlements in the Eastern Baltic: from Earlier Research to New Interpretations

Vilnius University Press Archaeologia Lituana ISSN 1392-6748 eISSN 2538-8738 2018, vol. 19, pp. 13–33 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ArchLit.2018.19.2 Fortified Settlements in the Eastern Baltic: From Earlier Research to New Interpretations Valter Lang Department of Archaeology, Institute of History and Archaeology University of Tartu 2 Jakobi St., 51014 Tartu, Estonia [email protected] A brief history of research and earlier interpretations of fortified settlements east of the Baltic Sea are provided in the first part of the article. The earlier research has resulted in the identification of the main area of the distribution of fortified settlements, the main chronology in the Late Bronze and Pre-Roman Iron Ages, and their general cultural and economic character. It has been thought that the need for protection – either because of outside danger or social tensions in society – was the main reason for the foundation of fortified sites. The second part of the article adds a new possibility of interpreting the phenomenon of fortified settlements, proceeding from ethnogenesis of the Finnic and Baltic peoples. It is argued that new material culture forms that took shape in the Late Bronze Age – including fortified settlements and find assemblages characteristic of them – derived at least partly from a new population arriving in several waves from the East-European Forest Belt. Keywords: fortified settlements, East Baltic, Bronze Age, ethnic interpretation. Įtvirtintos gyvenvietės Rytų Baltijos regione: nuo ankstesnių tyrimų prie naujų interpretacijų Pirmoje straipsnio dalyje pateikiama trumpa Rytų Baltijos regiono įtvirtintų gyvenviečių tyrinėjimų istorija ir ankstesnių tyrimų interpretacija. Ankstesnių tyrimų rezultatas – įtvirtintų gyvenviečių vėlyvojo žalvario ir ikiromėniškojo geležies amžiaus laikotarpio pagrindinės paplitimo teritorijos, principinės chronologijos bei pagrindinių kultūrinių ir ekonominių bruožų nustatymas. -

The Concept of Love in Lithuanian Folklore and Mythology

THE CONCEPT OF LOVE IN LITHUANIAN FOLKLORE AND MYTHOLOGY Doc dr. Daiva Šeškauskaitė Department of Social and Humanities Sciences Faculty of Forestry and Landscape Planing Kaunas Forestry and Environmental Engineering University of Applied Sciences Lithuania ABSTRACT Love is a reserved feeling, meaning amiability and complete internecine understanding. The concept of love has always been important for human world outlook and attitude. Love can have different meaning and expression – for some people it is a nice, warm feeling, a way of action and behaviour, for others it is nothing more than a sexual attraction. As there are different perceptions of love, there also exist few common love manifestations: love can be maternal, childish, juvenile, sexual. Love can also be felt for a home land, own nation, home. Naturally love can be expressed through the particular rituals, symbols and signs. Folk songs introduce four main lover characteristics: beauty, sweetness, kindness and boon. The later feature means that a girl/ boy is supposed to be well-set, to be pleasant and comfortable to touch which is very important when choosing a wife or a husband. Love in folklore is expressed through the common metaphorical and allegorical symbols, it doesn‘t sound as explicit word – more like a metaphor or epithet. Love in folklore can be perceived and felt very differently. Love like an action – love like... special person, essential possession. Prime personal characteristics, such as kindness, tenderness, humility, are the ones to light the love fire as well as beauty, artfulness, eloquence also help. Love is supposed to lead to the sacred sacrament of marriage. -

MESOLITHIC and NEOLITHIC HABITATION of the EASTERN BALTIC EE-2400 Tartu, Estonia and Institute of Latvian History, 19, Turgenev

[RADIOCARBON, VOL. 35, No. 3, 1993, P. 503-506] MESOLITHIC AND NEOLITHIC HABITATION OF THE EASTERN BALTIC ARVI LIIVA Institute of Zoology and Botany, Estonian Academy of Sciences, Vanemuise Street 21 EE-2400 Tartu, Estonia and ILZE LOZE Institute of Latvian History, 19, Turgenev Street, LV-1518 Riga, Latvia ABSTRACT. In this paper we consider the radiocarbon chronology of Mesolithic and Neolithic settlement sites in the eastern Baltic region. Dating of wood and charcoal from Estonian and Latvian sites establishes the periods (early, middle and late) within these epochs. We present 9014C dates, as yet unpublished in RADIOCARBON, produced by laboratories in Riga, Tallin, Tartu, Leningrad and Moscow. INTRODUCTION The Tartu, Vilnius and Leningrad laboratories radiocarbon dated samples from Mesolithic and Neolithic settlement sites of the eastern Baltic. Laboratories in Riga, Tallinn and Moscow also dated some samples; Tartu and Leningrad previously reported 36 dates (Vinogradov et al. 1966; Liiva, Ilves and Punning 1966; Dolukhanov 1970; Ilves, Punning and Liva 1970; Semyontsov et al. 1972; Dolukhanov et al. 1976). We have used 90 additional dates for our study. All 14C data presented here are uncorrected and uncalibrated. RADIOCARBON INVESTIGATIONS Radiocarbon investigations in the eastern Baltic have enabled us to establish an occupation history beginning with the Early Mesolithic. No samples were obtained from Late Paleolithic sites. The timing of the Early Mesolithic culture in Estonia and eastern Latvia was determined after dating seven samples from three habitation sites: Pulli in Estonia (5 samples), Zvejnieki II and Suagals in Latvia (2 samples). Occupation of the Pulli site, associated with the early phase of the Kunda culture, as are habitation sites of Latvia, is ascribed to 9600-9350 BP (Punning, Liiva and Ilves 1968; Ilves, Liiva and Punning 1974; Jaanits and Jaanits 1978). -

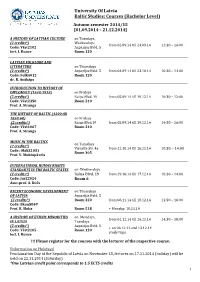

University of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level)

University Of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level) Autumn semester 2014/15 [01.09.2014 – 21.12.2014] A HISTORY OF LATVIAN CULTURE on Tuesdays, (2 credits*) Wednesdays from 02.09.14 till 24.09.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst2102 Azpazijas Bvld. 5 lect. I. Runce Room 120 LATVIAN FOLKLORE AND LITERATURE on Thursdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. 5 from 04.09.14 till 23.10.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: Folk4012 Room 120 dr. R. Auškāps INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF DIPLOMACY (1648-1918) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 10:30 – 12:00 Code: Vēst2350 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga THE HISTORY OF BALTIC (1200 till 1850-60) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd.19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 14:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst1067 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga MUSIC IN THE BALTICS on Tuesdays (2 credits*) Visvalža Str. 4a from 21.10.14 till 16.12.14 10:30. – 14:00 Code : MākZ1031 Room 305 Prof. V. Muktupāvels INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARTS IN THE BALTIC STATES on Wednesdays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 29.10.14 till 17.12.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: JurZ2024 Room 6 Asoc.prof. A. Kučs RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT on Thursdays OF LATVIA Azpazijas Bvld. 5 (2 credits*) Room 320 from 06.11.14 till 18.12.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Ekon5069 Prof. B. Sloka Room 518 + Monday, 10.11.14 A HISTORY OF ETHNIC MINORITIES on Mondays, from 01.12.14 till 16.12.14 14:30 – 18:00 IN LATVIA Tuesdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. -

Bachelor Theses 1996 - 2020

Bachelor Theses 1996 - 2020 ID Title Name Surname Year Supervisor Pages Notes Year 2020 Are individual stock prices more efficient than Jānis Beikmanis 2020 SSE Riga Student Research market-wide prices? Evidence on the evolution of 2020 Tālis Putniņš 49 01 Papers 2020 : 3 (225) Samuelson’s Dictum Pauls Sīlis 2020 Assessment of the Current Practices in the Justs Patmalnieks 2020 Viesturs Sosars 50 02 Magnetic Latvia Business Incubator Programs Kristaps Volks 2020 Banking business model development in Latvia Janis Cirulis 2020 Dmitrijs Kravceno 36 03 between 2014 and 2018 2020 Betting Markets and Market Efficiency: Evidence Laurynas Janusonis 2020 Tarass Buka 55 04 from Latvian Higher Football League Andrius Radiul 2020 Building a Roadmap for Candidate Experience in Jelizaveta Lebedeva 2020 Inga Gleizdane 53 05 the Recruitment Process Madara Osīte Company financial performance after receiving Ernests Pulks 2020 non-banking financing: Evidence from the Baltic 2020 Anete Pajuste 44 06 market Patriks Simsons Emīls Saulītis 2020 Consumer behavior change due to the emergence 2020 Aivars Timofejevs 41 07 of the free-floating car-sharing services in Riga Vitolds Škutāns 2020 Content Marketing in Latvian Tech Startups Dana Zueva 2020 Aivars Timofejevs 64 08 Corporate Social Responsibility: An Analysis of Laura Ramza 2020 Companies’ CSR Activities Relationship with Their 2020 Anete Pajuste 48 09 Financial Performance in the Baltic States Santa Usenko 2020 Determinants of default probabilities: Evidence Illia Hryzhenku 2020 Kārlis Vilerts 40 10 from -

The Construction of Pagan Identity in Lithuanian “Pagan Metal” Culture

VYTAUTO DIDŢIOJO UNIVERSITETAS SOCIALINIŲ MOKSLŲ FAKULTETAS SOCIOLOGIJOS KATEDRA Agnė Petrusevičiūtė THE CONSTRUCTION OF PAGAN IDENTITY IN LITHUANIAN “PAGAN METAL” CULTURE Magistro baigiamasis darbas Socialinės antropologijos studijų programa, valstybinis kodas 62605S103 Sociologijos studijų kryptis Vadovas Prof. Ingo W. Schroeder _____ _____ (Moksl. laipsnis, vardas, pavardė) (Parašas) (Data) Apginta _________________________ ______ _____ (Fakulteto/studijų instituto dekanas/direktorius) (Parašas) (Data) Kaunas, 2010 1 Table of contents SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................ 4 SANTRAUKA .................................................................................................................................... 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 8 I. THEORIZING ―SUBCULTURE‖: LOOKING AT SCIENTIFIC STUDIES .............................. 13 1.1. Overlooking scientific concepts in ―subcultural‖ research ..................................................... 13 1.2. Assumptions about origin of ―subcultures‖ ............................................................................ 15 1.3 Defining identity ...................................................................................................................... 15 1.3.1 Identity and ―subcultures‖ ................................................................................................ -

Ancient History of Latvia 10 500–1 800 BC at the End of the Glacial

ENG Ancient History of Latvia 10 500–1 800 BC At the end of the Glacial Period, approximately 14 000–12 000 years ago, the territory of Latvia became free from the ice sheet. The first human settlers arrived in this tundra landscape in the Late Paleolithic (10 500–9 000 BC), 11 000–12 000 years ago, following the reindeer and keeping to the major river valleys and the shore of the Baltic Ice Lake [3]*. Their material culture reveals affinities with the Swiderian Culture of Central and Western Europe. Natural conditions in the Mesolithic (9 000–5 400 BC) changed from cool and dry to warm and wet. People settled permanently on riverbanks and lakeshores, and subsisted from hunting, fishing and gathering wild plants. These people made weapons and tools from flint, antler, bone and wood [4,5]. They belonged to the Kunda Culture, which extended across a large area of the East Baltic. The beginning of the Neolithic (5 400–1 800 BC) was marked by the introduction of pottery-making [7]. The Neolithic also witnessed the beginnings of animal husbandry and agriculture. In the Early Neolithic (5 400–4 100 BC), the Narva Culture developed locally on the bases of the Kunda Culture. In the Middle Neolithic (4 100–2 900 BC), the representatives of the Pit-Comb Ware Culture arrived in the territory of Latvia from the north-east, regarded as the ancestors of the Finnic peoples [10–12]. In this period, amber was also extensively worked. In western Latvia there was the Sārnate Culture [9] while in the eastern Latvia – the Piestiņa Culture [13] that continued the tradition of the Narva Culture. -

Structural-Semantic Analysis and Some Peculiarities of Lithuanian Novelle Tales

STRUCTURAL-SEMANTIC ANALYSIS AND SOME PECULIARITIES OF LITHUANIAN NOVELLE TALES Radvilė Racėnaitė Abstract: The genre diversity of narrative folklore is represented in interna- tionally accepted classification of tales and legends proposed by Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. However, the preparation of national catalogues based on Aarne-Thompson system encounters problems, given that there exist narra- tives with contradictory genre particularities and they do not easily fall into the limits of one genre group. In her search for more objective criteria for classifica- tion, the compiler of the revised “Catalogue of Lithuanian narrative folklore” Bronislava Kerbelytė has taken the above-mentioned imperfections into con- sideration. She has worked out an innovatory structural-semantic analysis of folk texts, based on the investigation of structural traits and on underlying semantic features of folk narratives. We will base our investigation on the prin- ciples of this analysis, as it seems to have prospects. The article aims at dis- closing the main structural and semantic peculiarities of Lithuanian novelle tales by means of structural-semantic and comparative method of research. The theoretical statements are illustrated by the so-called “Tales of Fate” / “die Schicksalserzählungen” (AT 930–949), which define some aspects of an atti- tude towards fate and death in Lithuanian traditional culture. The assumption is proposed that structural-semantic analysis enables to define the function, the boundaries, and the development of folklore genres more precisely. Key words: death, fate, Lithuanian novelle tales, narrative folklore, seman- tics, structure, tales of fate INTRODUCTION The genre diversity of narrative folklore is represented in internationally ac- cepted classification of tales and legends proposed by Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. -

188189399.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Zhytomyr State University Library МІНІСТЕРСТВО ОСВІТИ І НАУКИ УКРАЇНИ ЖИТОМИРСЬКИЙ ДЕРЖАВНИЙ УНІВЕРСИТЕТ ІМЕНІ ІВАНА ФРАНКА Кваліфікаційна наукова праця на правах рукопису КУКУРЕ СОФІЯ ПАВЛІВНА УДК 213:257:130.11 ДИСЕРТАЦІЯ ЕТНІЧНІ РЕЛІГІЇ БАЛТІЙСЬКИХ НАРОДІВ ЯК ЧИННИК НАЦІОНАЛЬНО-КУЛЬТУРНОЇ ІДЕНТИФІКАЦІЇ 09.00.11 – релігієзнавство філософські науки Подається на здобуття наукового ступеня кандидата філософських наук Дисертація містить результати власних досліджень. Використання ідей, результатів і текстів інших авторів мають посилання на відповідне джерело _______________ Кукуре С. П. Науковий керівник – доктор історичних наук, професор Гусєв Віктор Іванович Житомир – 2018 2 АНОТАЦІЯ Кукуре С. П. Етнічні релігії балтійських народів як чинник національно-культурної ідентифікації. – Кваліфікаційна наукова праця на правах рукопису. Дисертація на здобуття наукового ступеня кандидата філософських наук (доктора філософії) за фахом 09.00.11 «Релігієзнавство, філософські науки». – Житомирський державний університет імені Івана Франка Міністерства освіти і науки України, Житомир, 2019. Вперше в українському релігієзнавстві досліджено етнічні релігії балтійських народів, які виступали та виступають чинником національно- культурної ідентифікації в зламні моменти їх історії, коли виникала загроза асиміляції або зникнення (насильницька християнізації часів Середньовіччя, становлення державності в першій половині ХХ століття), а також на сучасному етапі, коли -

The Shared Lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic

THE SHARED LEXICON OF BALTIC, SLAVIC AND GERMANIC VINCENT F. VAN DER HEIJDEN ******** Thesis for the Master Comparative Indo-European Linguistics under supervision of prof.dr. A.M. Lubotsky Universiteit Leiden, 2018 Table of contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Background topics 3 2.1. Non-lexical similarities between Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2. The Prehistory of Balto-Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2.1. Northwestern Indo-European 3 2.2.2. The Origins of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 4 2.3. Possible substrates in Balto-Slavic and Germanic 6 2.3.1. Hunter-gatherer languages 6 2.3.2. Neolithic languages 7 2.3.3. The Corded Ware culture 7 2.3.4. Temematic 7 2.3.5. Uralic 9 2.4. Recapitulation 9 3. The shared lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 11 3.1. Forms that belong to the shared lexicon 11 3.1.1. Baltic-Slavic-Germanic forms 11 3.1.2. Baltic-Germanic forms 19 3.1.3. Slavic-Germanic forms 24 3.2. Forms that do not belong to the shared lexicon 27 3.2.1. Indo-European forms 27 3.2.2. Forms restricted to Europe 32 3.2.3. Possible Germanic borrowings into Baltic and Slavic 40 3.2.4. Uncertain forms and invalid comparisons 42 4. Analysis 48 4.1. Morphology of the forms 49 4.2. Semantics of the forms 49 4.2.1. Natural terms 49 4.2.2. Cultural terms 50 4.3. Origin of the forms 52 5. Conclusion 54 Abbreviations 56 Bibliography 57 1 1. -

Were the Baltic Lands a Small, Underdeveloped Province in a Far

3 Were the Baltic lands a small, underdeveloped province in a far corner of Europe, to which Germans, Swedes, Poles, and Russians brought religion, culture, and well-being and where no prerequisites for independence existed? Thus far the world extends, and this is the truth. Tacitus of the Baltic Lands He works like a Negro on a plantation or a Latvian for a German. Dostoyevsky The proto-Balts or early Baltic peoples began to arrive on the shores of the Baltic Sea nearly 4,000 years ago. At their greatest extent, they occupied an area some six times as large as that of the present Baltic peoples. Two thousand years ago, the Roman Tacitus wrote about the Aesti tribe on the shores of the #BMUJDBDDPSEJOHUPIJN JUTNFNCFSTHBUIFSFEBNCFSBOEXFSFOPUBTMB[ZBT many other peoples.1 In the area that presently is Latvia, grain was already cultivated around 3800 B.C.2 Archeologists say that agriculture did not reach southern Finland, only some 300 kilometers away, until the year 2500 B.C. About 900 AD Balts began establishing tribal realms. “Latvians” (there was no such nation yet) were a loose grouping of tribes or cultures governed by kings: Couronians (Kurshi), Latgallians, Selonians and Semigallians. The area which is known as -BUWJBUPEBZXBTBMTPPDDVQJFECZB'JOOP6HSJDUSJCF UIF-JWT XIPHSBEVBMMZ merged with the Balts. The peoples were further commingled in the wars which Estonian and Latvian tribes waged with one another for centuries.3 66 Backward and Undeveloped? To judge by findings at grave sites, the ancient inhabitants in the area of Latvia were a prosperous people, tall in build.