The Rose and Blood: Images of Fire in Baltic Mythology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folklór Baltských Zemí Jako Zdroj Pro Studium Předkřesťanských Tradic Starých Baltů

4 JAK ROzuměT „POHANSKÝM RELIKTům“: FolKLÓR BALTSKÝCH ZEMÍ JAKO ZDROJ PRO STUDIUM PředKřesťANSKÝCH TRADIC STARÝCH BALTů Anglický termín folklore, přeložitelný do češtiny jako „lidová tradice“ či „lidové vě- dění“, začal být evropskými vzdělanci užíván před polovinou 19. století.1 V kon- textu historie moderní vědy se jedná o zásadní epochu, kdy vznikala v sekulární podobě většina současných humanitních oborů, včetně organizovaného studia folklóru. Evropská města prodělávala touto dobou druhou vlnu „industriální revoluce“, spojenou s modernizací, masovými imigracemi venkovské populace a pozvolnou „detradicionalizací“ v širších vrstvách společnosti. Modernizační procesy přitom neovlivňovaly pouze kulturní prostředí měst, ale prosakovaly v různých podobách i na venkov. Důsledkem toho zde začínají mizet dlouhodobě konzervované kulturní elementy, nezřídka poměrně „archaického“ stáří. Zároveň s těmito procesy však již druhá generace romantických intelektuálů mezi Atlan- tikem a Volhou usilovně studuje kulturní dějiny dílčích (obvykle svých vlastních) národů, zpravidla se zvláštním zřetelem k jejich historické genezi a identickým specifikům.2 Tradice udržované venkovskými obyvateli, do 18. století městskou inteligencí spíše ignorované či opovrhované, získávají ještě před rokem 1800 ros- toucí pozornost a následně i roli „stavebního materiálu“ při procesu „budování“ národních identit.3 1 Za původce anglického termínu folklore, který vytlačil starší latinismus popular antiquities, bývá obvykle považován spisovatel a amatérský historik William John Thoms (1803–1885). Významnou inspiraci pro jeho zájem o lidové kultury představovala díla Jacoba Grimma (1785–1863) a Wilhelma Grimma (1786–1859), průkopníků německé (a v podstatě i evropské) folkloristiky. 2 Spojitost nacionalismu a folkloristiky během 18.–20. století analyzuje např. Doorman, Martin, Romantický řád, Praha: Prostor 2008, 203–224. 3 K folkloristice a její genezi viz např. -

The Lithuanian Apidėmė: a Goddess, a Toponym, and Remembrance Vykintas Vaitkevičius, University of Klaipeda

Scandinavian World. Minneapolis / London: [Sveinbjörn Egilsson, Rafn Þ. Gudmundsson & Rasmus University of Minnesota Press. Rask (eds.).] 1827. Saga Olafs konungs Power, Rosemary. 1985. “‘An Óige, an Saol agus an Tryggvasonar. Nidrlag sogunnar med tilheyrandi Bás’, Feis Tighe Chonáin and ‘Þórr’s Visit to tattum. Fornmanna sögur 3: Niðrlag sögu Ólafs Útgarða-Loki’”. Béaloideas 53: 217–294. konúngs Tryggvasonar með tilheyrandi þáttum. Robinson, Tim. 2008. Stones of Aran: Pilgrimage. Kaupmannahøfn: Harðvíg Friðrek Popp. Introduction by Robert Macfarlane. London: Faber Thompson, Stith. 1955–1958. Motif-Index of Folk- & Faber. Literature: A Classification of Narrative Elements in Robinson, Tim. 2009. Stones of Aran: Labyrinth. Folktales, Ballads, Myths, Fables, Mediaeval Introduction by John Elder. New York: New York Romances, Exempla, Fabliaux, Jest-Books, and Review of Books. Local Legends. Rev. & enlarged edn. Bloomington / Schama, Simon. 1996. Landscape and Memory. New Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. Available at: York: Vintage Books. https://www.ualberta.ca/~urban/Projects/English/M Sigurgeir Steingrímsson, Ólafur Halldórsson, & Peter otif_Index.htm (last accessed 17 October 2017). Foote. 2003. Biskupa sögur 1: Síðari hluti – Tietz, Andrea. 2012. Die Saga von Þorsteinn sögutextar. Íslenzk Fornrit 15. Reykjavík: Hið bæjarmagn – Saga af Þorsteini bæjarmagni: Íslenzka Fornritafélag. Übersetzung und Kommentar. Münchner Smith, Jonathan Z. 1987. To Take Place: Toward Nordistische Studien 12. München: Utz. Theory in Ritual. Chicago / London: University of Chicago Press. The Lithuanian Apidėmė: A Goddess, a Toponym, and Remembrance Vykintas Vaitkevičius, University of Klaipeda Abstract: This paper is devoted to the Lithuanian apidėmė, attested since the 16th century as the name of a goddess in the Baltic religion, as a term for the site of a former farmstead relocated to a new settlement during the land reform launched in 1547–1557, and later as a widespread toponym. -

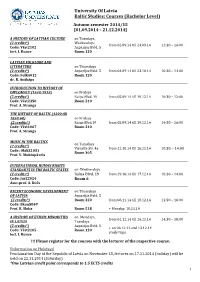

University of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level)

University Of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level) Autumn semester 2014/15 [01.09.2014 – 21.12.2014] A HISTORY OF LATVIAN CULTURE on Tuesdays, (2 credits*) Wednesdays from 02.09.14 till 24.09.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst2102 Azpazijas Bvld. 5 lect. I. Runce Room 120 LATVIAN FOLKLORE AND LITERATURE on Thursdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. 5 from 04.09.14 till 23.10.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: Folk4012 Room 120 dr. R. Auškāps INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF DIPLOMACY (1648-1918) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 10:30 – 12:00 Code: Vēst2350 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga THE HISTORY OF BALTIC (1200 till 1850-60) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd.19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 14:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst1067 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga MUSIC IN THE BALTICS on Tuesdays (2 credits*) Visvalža Str. 4a from 21.10.14 till 16.12.14 10:30. – 14:00 Code : MākZ1031 Room 305 Prof. V. Muktupāvels INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARTS IN THE BALTIC STATES on Wednesdays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 29.10.14 till 17.12.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: JurZ2024 Room 6 Asoc.prof. A. Kučs RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT on Thursdays OF LATVIA Azpazijas Bvld. 5 (2 credits*) Room 320 from 06.11.14 till 18.12.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Ekon5069 Prof. B. Sloka Room 518 + Monday, 10.11.14 A HISTORY OF ETHNIC MINORITIES on Mondays, from 01.12.14 till 16.12.14 14:30 – 18:00 IN LATVIA Tuesdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. -

The Construction of Pagan Identity in Lithuanian “Pagan Metal” Culture

VYTAUTO DIDŢIOJO UNIVERSITETAS SOCIALINIŲ MOKSLŲ FAKULTETAS SOCIOLOGIJOS KATEDRA Agnė Petrusevičiūtė THE CONSTRUCTION OF PAGAN IDENTITY IN LITHUANIAN “PAGAN METAL” CULTURE Magistro baigiamasis darbas Socialinės antropologijos studijų programa, valstybinis kodas 62605S103 Sociologijos studijų kryptis Vadovas Prof. Ingo W. Schroeder _____ _____ (Moksl. laipsnis, vardas, pavardė) (Parašas) (Data) Apginta _________________________ ______ _____ (Fakulteto/studijų instituto dekanas/direktorius) (Parašas) (Data) Kaunas, 2010 1 Table of contents SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................ 4 SANTRAUKA .................................................................................................................................... 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 8 I. THEORIZING ―SUBCULTURE‖: LOOKING AT SCIENTIFIC STUDIES .............................. 13 1.1. Overlooking scientific concepts in ―subcultural‖ research ..................................................... 13 1.2. Assumptions about origin of ―subcultures‖ ............................................................................ 15 1.3 Defining identity ...................................................................................................................... 15 1.3.1 Identity and ―subcultures‖ ................................................................................................ -

Sūduvių Knygelės Nuorašų Formalioji Analizė Bei Analitinė Eksplikacija1

Archivum Lithuanicum 20, 2018 ISSN 1392-737X, p. 89– 124 Rolandas Kregždys Lietuvos kultūros tyrimų institutas, Vilnius Sūduvių knygelės nuorašų formalioji analizė bei analitinė eksplikacija1 Pro captu lectoris habent ſua fata libelli terentianus maurus, De litteris syllabis pedibus et metris, cap. ii.1286 0. etnomitoloGinio ŠALTINIO publiKAVIMO problema Wil- Helmo mannHardto veiKale LETTO-PREUSSISCHE GÖTTERLEHRE. Sūduvių knygelė (toliau – SK) yra sutartinis keliais rankraščių variantais, o vėliau ir spausdin- tomis knygelėmis, platintų žinių apie sūduvius šaltinio pavadinimas. tai viena iš dviejų vakarų baltų kalbų, dar vadinama jotvingių2, šnekėjusios genties bene išsa- miausias ir svarbiausias etnokultūrinės tradicijos, užfiksuotos reformacijos laikotar- piu3, aprašas. pirmasis tokį šaltinio pavadinimą vartojo antonis mierzyńskis (1829–1907), juo įvardydamas ne SK nuorašus, bet Jeronimo maleckio (1525/1526–1583/1584) publika- ciją ir jos perspaudus: „книжку, которую для краткости назовемъ ‘Судав скою’“4 / „książeczkę, którą dla krótkości nazwijmy ‘sudawską’“5. tiesa, anksčiau menkina- mosios konotacijos lytį Büchlein ‘knygelė’ yra minėjęs mozūrų kultūros tyrėjas, folk- loristas, leidėjas ir istorikas Janas Karolis sembrzyckis (1856–1919), taip vadindamas Jeronimo maleckio leidinį6. mannhardto monografijoje Letto-Preussische Götterlehre (toliau – WMh) taip pat nurodomas identiškas įvardijimas Sudauerbüchlein7, tačiau jo autorystės priskirti šiam 1 publikacija parengta 2017–2020 m. vykdant kuršių kalbą (mažiulis 1987, 83–84; LKE 69; nacionalinės reikšmės mokslo tiriamąjį dar žr. dini 2000, 213). Jotvingiai, gyvenę projektą „mokslo monografijų ciklo Baltų pietų lietuvoje, šiaurės rytų lenkijoje bei mitologemų etimologijos žodynas II: Sūduvių vakarų baltarusijoje, išnyko nepalikę „jo- knygelė 2-ojo tomo rengimas ir leidyba“ kių rašto paminklų“ (vanagas 1987, 22). (nr. p-mip-17-4), finansuojamą lietuvos 3 plg. brauer 2008, 155. mokslo tarybos pagal veiklos kryptį 4 Мѣржинскiй 1899, 63. -

188189399.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Zhytomyr State University Library МІНІСТЕРСТВО ОСВІТИ І НАУКИ УКРАЇНИ ЖИТОМИРСЬКИЙ ДЕРЖАВНИЙ УНІВЕРСИТЕТ ІМЕНІ ІВАНА ФРАНКА Кваліфікаційна наукова праця на правах рукопису КУКУРЕ СОФІЯ ПАВЛІВНА УДК 213:257:130.11 ДИСЕРТАЦІЯ ЕТНІЧНІ РЕЛІГІЇ БАЛТІЙСЬКИХ НАРОДІВ ЯК ЧИННИК НАЦІОНАЛЬНО-КУЛЬТУРНОЇ ІДЕНТИФІКАЦІЇ 09.00.11 – релігієзнавство філософські науки Подається на здобуття наукового ступеня кандидата філософських наук Дисертація містить результати власних досліджень. Використання ідей, результатів і текстів інших авторів мають посилання на відповідне джерело _______________ Кукуре С. П. Науковий керівник – доктор історичних наук, професор Гусєв Віктор Іванович Житомир – 2018 2 АНОТАЦІЯ Кукуре С. П. Етнічні релігії балтійських народів як чинник національно-культурної ідентифікації. – Кваліфікаційна наукова праця на правах рукопису. Дисертація на здобуття наукового ступеня кандидата філософських наук (доктора філософії) за фахом 09.00.11 «Релігієзнавство, філософські науки». – Житомирський державний університет імені Івана Франка Міністерства освіти і науки України, Житомир, 2019. Вперше в українському релігієзнавстві досліджено етнічні релігії балтійських народів, які виступали та виступають чинником національно- культурної ідентифікації в зламні моменти їх історії, коли виникала загроза асиміляції або зникнення (насильницька християнізації часів Середньовіччя, становлення державності в першій половині ХХ століття), а також на сучасному етапі, коли -

The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade

Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 18 January 2017 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PRUSSIAN CRUSADE The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade explores the archaeology and material culture of the Crusade against the Prussian tribes in the thirteenth century, and the subsequent society created by the Teutonic Order that lasted into the six- teenth century. It provides the first synthesis of the material culture of a unique crusading society created in the south-eastern Baltic region over the course of the thirteenth century. It encompasses the full range of archaeological data, from standing buildings through to artefacts and ecofacts, integrated with writ- ten and artistic sources. The work is sub-divided into broadly chronological themes, beginning with a historical outline, exploring the settlements, castles, towns and landscapes of the Teutonic Order’s theocratic state and concluding with the role of the reconstructed and ruined monuments of medieval Prussia in the modern world in the context of modern Polish culture. This is the first work on the archaeology of medieval Prussia in any lan- guage, and is intended as a comprehensive introduction to a period and area of growing interest. This book represents an important contribution to promot- ing international awareness of the cultural heritage of the Baltic region, which has been rapidly increasing over the last few decades. Aleksander Pluskowski is a lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at the University of Reading. Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 -

Vaitkevicius Lithmill 2015 B.Pdf

~·· • ~ ,. -• ·- ~- • - -:2• ---- • i ----,. - ~-~ -:lf' ..... ~~ ~ • __.,_II. "' .• f ,. ''Ii ii/'h .... - t:. '- .. ~ ~ .:· "' '1k-~ . ..- -- i! - " Ji i' 1' ! •• - 2 " I ; I 1 l /'tt "'= - E • I i _,._-.":_ ft- s . .i . #' A_ •1 - ·-- ~· ••- l .A .f!.. ~! "--·'- 11 t..~ -.:z A "' -••• ..,. _;'- - I lr ·"' =:t·1 t,-=, " l. \- l.i. l .1. -- -..,. is tor rt an ' ,L) Vilnius Academv of Arts Press, 201 ' 0 Fire- the Centre of the Ancient Baltic Religion By prioritising wril1en sources, researchers studying the Baltic Region have made inexcusably little reference to the factual information that has been gathered during archaeological investigations. Up untiltoday. thousands ofsquare metres ofterri tory of archaeological monuments have already been explored and volu mes of reports written, while the shelves of muse ums are rich with fi nds. Thorough studies of this data and its relation to the fac ts of language, folklore, ethnography and history have forced us to fundamentall y change our at1itude towards our understanding of the Baltic religion, and, with the beginning of the 21" c., to correct conceptions made about religion itsclf. Approaching the past with modern eyes, it is common to view religion as a separate field that was clissociated from everyday life and in order to understand it, 19 studies in to sacred sites and buria! si tes provide the largest benefit. This is, albeit, only partiall y true. 1l1e Balts preserved a significant a mount of pre-Christian sacral terms such as the Lithuanian alka which signifies a sacred grove and a place fo r offerings, and the Latvian elks which stands for idol or god. -

Transformations of the Lithuanian God Perk\Nas

Transformations of the Lithuanian God Perk\nas Nijol] Laurinkien] In the article, later substitutions for the god Perkunas are analysed. Most frequently appear the names of the prophet Eliah (Alijošius) and St. George (Jurgis) as the Christian replacements diffused from the Lithuanian region, which borders on Belarus where converting to Christianity began earlier. With the fall of the old culture a great many traditions indicated the god of thunder as undergoing a complete transformation into new characters, mostly those of modern religion. Lithuanian mythology also gives evidence of similar processes. The article aims at an analysis of further equivalents of Perk'nas, which reflect the mentioned process, as well as an attempt to delineate the possible reasons for these substitutes obtained by the god of thunder and their prevalence in Lithuania. The most common substitutes of Perk'nas are the prophet Elijah (Elijošius, Alijošius) and St George (Jurgis). These Christian characters as equivalents to the god of thunder are also known among eastern Slavs. Therefore, a logical question follows on the nature of such a peculiar concurrence, which will receive due attention in the article. Lithuanian folklore often observes Elijah mentioned together with Enoch (both, as the Bible suggests, having been so close to God that they were brought to dwell in heaven when still alive). Legends about Elijah and Enoch feature them being related to the motifs of old religion and those of Christianity (LPK 3459). From the latter, associations of the mentioned characters with the god of thunder can be obviously defined: when Elijah or Enoch rides in the heaven, it thunders and lightning is flashing: Seniai, labai seniai, kada dar Adomo ir Ievos nebuvę, Dievas sutvcrc AlijošiC ir Anoką. -

Greimo Mitologijos Tyrimų Takais

SUKAKTYS Greimo mitologijos tyrimų takais DAIVA VAITKEVIČIENĖ Lietuvių literatūros ir tautosakos institutas ANOTACIJA. Nors nuo Algirdo Juliaus Greimo mitologijos studijų Apie dievus ir žmones (1979) ir Tautos atminties beieškant (1990) pasirodymo jau praėjo keli dešimtmečiai, bet iki šiol nėra plačiau aptartas jo mitologijos tyrimų kelias. Straipsnyje pateikiama Greimo mitologijos darbų (įskaitant ir skelbtuosius prancūzų kalba) chronologinė apžvalga, išryškinamos jo mitologijos studijų prielaidos ir siekiai, atskleidžiamas Greimo požiūris į mitologijos tyrimų būklę Lietuvoje. Atliktas tyrimas leidžia teigti, kad lietuvių mitologija Greimui buvo ne tik bendrųjų semiotikos tyrimų „bandomasis laukas“, bet ir galimybė realizuoti save kaip kultūros istoriką ir religijotyrininką, o kartu, jo paties žodžiais tariant, „atiduoti skolą Lietuvai“. Ši sugrąžinta „skola“ tebelaukia deramo įvertinimo ir pradėtų darbų tąsos. RAKTAŽODŽIAI: Greimas, semiotika, lietuvių mitologija, indoeuropiečių mitologija, pasakos, mitai. Algirdas Julius Greimas − daugialypė asmenybė, kurią Lietuvoje daugiausia žinome dviem vardais − semiotiko ir mitologo. Arūnas Sverdiolas teigia: Yra du Greimai. Pasaulinio garso mokslininkas, kūręs semiotiką, kurios svarbą huma- nitariniams ir socialiniams mokslams jis pats gretino su matematikos svarba gamtos mokslams. Greimas taip pat yra palikęs puikių įvairiausio pobūdžio tekstų semiotinės analizės pavyzdžių. Šalia tarpsta jo semiotiniai lietuvių mitologijos tyrinėjimai, įsira- šantys į Georges’o Dumézilio ir Claude’o Lévi-Strausso -

LITUANUS Cumulative Index 1954-2004 (PDF)

LITUANUS Cumulative Index 1954-2004 Art and Artists [Aleksa, Petras]. See Jautokas. 23:3 (1977) 59-65. [Algminas, Arvydas]. See Matranga. 31:2 (1985) 27-32. Anderson, Donald J. “Lithuanian Bookplates Ex Libris.” 26:4 (1980) 42-49. ——. “The Art of Algimantas Kezys.” 27:1 (1981) 49-62. ——. “Lithuanian Art: Exhibition 90 ‘My Religious Beliefs’.” 36:4 (1990) 16-26. ——. “Lithuanian Artists in North America.” 40:2 (1994) 43-57. Andriußyt∂, Rasa. “Rimvydas Jankauskas (Kampas).” 45:3 (1999) 48-56. Artists in Lithuania. “The Younger Generation of Graphic Artists in Lithuania: Eleven Reproductions.” 19:2 (1973) 55-66. [Augius, Paulius]. See Jurkus. 5:4 (1959) 118-120. See Kuraus- kas. 14:1 (1968) 40-64. Außrien∂, Nora. “Außrin∂ Marcinkeviçi∆t∂-Kerr.” 50:3 (2004) 33-34. Bagdonas, Juozas. “Profile of an Artist.” 29:4 (1983) 50-62. Bakßys Richardson, Milda. ”Juozas Jakßtas: A Lithuanian Carv- er Confronts the Venerable Oak.” 47:2 (2001) 4, 19-53. Baltrußaitis, Jurgis. “Arts and Crafts in the Lithuanian Home- stead.” 7:1 (1961) 18-21. ——. “Distinguishing Inner Marks of Roerich’s Painting.” Translated by W. Edward Brown. 20:1 (1974) 38-48. [Balukas, Vanda 1923–2004]. “The Canvas is the Message.” 28:3 (1982) 33-36. [Banys, Nijol∂]. See Kezys. 43:4 (1997) 55-61. [Barysait∂, DΩoja]. See Kuç∂nas-Foti. 44:4 (1998) 11-22. 13 ART AND ARTISTS [Bookplates and small art works]. Augusts, Gvido. 46:3 (2000) 20. Daukßait∂-Katinien∂, Irena. 26:4 (1980) 47. Eidrigeviçius, Stasys 26:4 (1980) 48. Indraßius, Algirdas. 44:1 (1998) 44. Ivanauskait∂, Jurga. 48:4 (2002) 39. -

Between National and Academic Agendas Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940

BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Other titles in the same series Södertörn Studies in History Git Claesson Pipping & Tom Olsson, Dyrkan och spektakel: Selma Lagerlöfs framträdanden i offentligheten i Sverige 1909 och Finland 1912, 2010. Heiko Droste (ed.), Connecting the Baltic Area: The Swedish Postal System in the Seventeenth Century, 2011. Susanna Sjödin Lindenskoug, Manlighetens bortre gräns: tidelagsrättegångar i Livland åren 1685–1709, 2011. Anna Rosengren, Åldrandet och språket: En språkhistorisk analys av hög ålder och åldrande i Sverige cirka 1875–1975, 2011. Steffen Werther, SS-Vision und Grenzland-Realität: Vom Umgang dänischer und „volksdeutscher” Nationalsozialisten in Sønderjylland mit der „großgermanischen“ Ideologie der SS, 2012. Södertörn Academic Studies Leif Dahlberg och Hans Ruin (red.), Fenomenologi, teknik och medialitet, 2012. Samuel Edquist, I Ruriks fotspår: Om forntida svenska österledsfärder i modern historieskrivning, 2012. Jonna Bornemark (ed.), Phenomenology of Eros, 2012. Jonna Bornemark och Hans Ruin (eds), Ambiguity of the Sacred, 2012. Håkan Nilsson (ed.), Placing Art in the Public Realm, 2012. Lars Kleberg and Aleksei Semenenko (eds), Aksenov and the Environs/Aksenov i okrestnosti, 2012. BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Södertörns högskola Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image, taken from Latvijas Universitāte Illūstrācijās, p. 10. Gulbis, Riga, 1929. Cover: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson and Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Studies in History 13 ISSN 1653-2147 Södertörn Academic Studies 51 ISSN 1650-6162 ISBN 978-91-86069-52-0 Contents Foreword ......................................................................................................................................