The Role of Folklore in the Formation of Latvian Visual Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Systems in Transition

61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 1 03/03/2020 09:55 Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Vol. Health Systems in Transition Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Health Systems in Transition: in Transition: Health Systems C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Latvia Latvia Health system review Daiga Behmane Alina Dudele Anita Villerusa Janis Misins The Observatory is a partnership, hosted by WHO/Europe, which includes other international organizations (the European Commission, the World Bank); national and regional governments (Austria, Belgium, Finland, Kristine Klavina Ireland, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the Veneto Region of Italy); other health system organizations (the French National Union of Health Insurance Funds (UNCAM), the Dzintars Mozgis Health Foundation); and academia (the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and the Giada Scarpetti London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)). The Observatory has a secretariat in Brussels and it has hubs in London at LSE and LSHTM) and at the Berlin University of Technology. HiTs are in-depth profiles of health systems and policies, produced using a standardized approach that allows comparison across countries. They provide facts, figures and analysis and highlight reform initiatives in progress. Print ISSN 1817-6119 Web ISSN 1817-6127 61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 2 03/03/2020 09:55 Giada Scarpetti (Editor), and Ewout van Ginneken (Series editor) were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European -

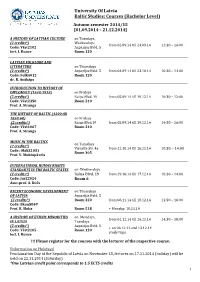

University of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level)

University Of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level) Autumn semester 2014/15 [01.09.2014 – 21.12.2014] A HISTORY OF LATVIAN CULTURE on Tuesdays, (2 credits*) Wednesdays from 02.09.14 till 24.09.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst2102 Azpazijas Bvld. 5 lect. I. Runce Room 120 LATVIAN FOLKLORE AND LITERATURE on Thursdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. 5 from 04.09.14 till 23.10.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: Folk4012 Room 120 dr. R. Auškāps INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF DIPLOMACY (1648-1918) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 10:30 – 12:00 Code: Vēst2350 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga THE HISTORY OF BALTIC (1200 till 1850-60) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd.19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 14:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst1067 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga MUSIC IN THE BALTICS on Tuesdays (2 credits*) Visvalža Str. 4a from 21.10.14 till 16.12.14 10:30. – 14:00 Code : MākZ1031 Room 305 Prof. V. Muktupāvels INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARTS IN THE BALTIC STATES on Wednesdays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 29.10.14 till 17.12.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: JurZ2024 Room 6 Asoc.prof. A. Kučs RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT on Thursdays OF LATVIA Azpazijas Bvld. 5 (2 credits*) Room 320 from 06.11.14 till 18.12.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Ekon5069 Prof. B. Sloka Room 518 + Monday, 10.11.14 A HISTORY OF ETHNIC MINORITIES on Mondays, from 01.12.14 till 16.12.14 14:30 – 18:00 IN LATVIA Tuesdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. -

Malevich's Russian Peasant Paintings During the First Five-Year Plan

The NEP Era: Soviet Russia 1921-1928, 8 (2014), 1-24. ARTICLES / СТАТЬИ MARIE GASPER-HULVAT Proletarian Credibility? Malevich’s Russian Peasant Paintings during the First Five-Year Plan During the years immediately before and after the 1917 October Revo- lution, the prominent Avant-Garde artist Kazimir Malevich (1878-1935) enjoyed renown in Russian art circles for his signature, abstract work. His nonobjective “Suprematist” style constituted one of the first models of purely abstract, non-representational painting in the modernist tradition of Western art. If the primary subject matter that Malevich’s work was con- cerned with is geometric forms, the second most recognizable content of Malevich’s paintings would be the Russian peasant. Not all of his work was abstract, and those paintings which do represent identifiable imagery have a notable tendency to favor rural subject matter, both landscapes and their inhabitants. In fact, Malevich began his career as a painter depicting peasant figures, prior to developing his signature style of abstraction in 1915. After his purely abstract period concluded in the mid-1920s, similar peasant themes reemerged in his work at the turn of the 1930s.1 While peasant imagery from early in Malevich’s career largely reflects the concerns of a young artist grappling with West European art historical precedents adapted to a Slavic context, I contend that his later peasant works engaged with the complex set of historical and political circum- stances of the early Stalinist era. Other scholars have explained how the artist’s motivations for creating the later peasant works were multifaceted and related significantly to his philosophical treatises regarding the essen- tial nature of art and humanity.2 Another set of scholars has read these images as reactions to contemporary political events.3 1. -

Latviešu-Lībiešu-Angļu Sarunvārdnīca Leţkīel-Līvõkīel-Engliškīel Rõksõnārōntõz Latvian-Livonian-English Phrase Book

Valda Šuvcāne Ieva Ernštreite Latviešu-lībiešu-angļu sarunvārdnīca Leţkīel-līvõkīel-engliškīel rõksõnārōntõz Latvian-Livonian-English Phrase Book © Valda Šuvcāne 1999 © Ieva Ernštreite 1999 © Eraksti 2005 ISBN-9984-771-74-1 68 lpp. / ~ 0.36 MB SATURS SIŽALI CONTENTS I. IEVADS ĪEVAD INTRODUCTION __________________________________________________________________ I.1. PRIEKŠVĀRDS 5 EĆĆISÕNĀ 6 FOREWORD 6 I.2. LĪBIEŠI, VIŅU VALODA UN RAKSTĪBA 7 LĪVLIST, NÄNT KĒĻ JA KĒRAVĪŢ LIVONIANS, THEIR LANGUAGE AND ORTOGRAPHY 12 I.3. NELIELS IESKATS LĪBIEŠU VALODAS GRAMATIKĀ 9 LĪTÕ IĻ LĪVÕ GRAMĀTIK EXPLANATORY NOTES ON THE MAIN FEATURES OF THE LIVONIAN SPELLING AND PRONUNCIATION 14 _____________________________________________________________________________ II. BIEŽĀK LIETOTĀS FRĀZES SAGGÕLD KȬLBATÕT FRĀZÕD COMMON USED PHRASES __________________________________________________________________ II.1. SASVEICINĀŠANĀS UN ATVADĪŠANĀS 16 TĒRIŅTÕMI JA JUMĀLÕKS JETĀMI GREETINGS II.2. IEPAZĪŠANĀS UN CIEMOŠANĀS 16 TUNDIMI JA KILĀSTIMI INTRODUCING PEOPLE, VISITING PEOPLE II.3. BIOGRĀFIJAS ZIŅAS 17 BIOGRĀFIJ TEUTÕD PERSON'S BIOGRAPHY II.4. PATEICĪBAS, LĪDZJŪTĪBAS UN PIEKLĀJĪBAS IZTEICIENI 18 TIENĀNDÕKST, ĪŅÕZTŪNDIMI JA ANDÕKS ĀNDAMI SÕNĀD EXPRESSING GRATITUDE, POLITE PHRASES II.5. LŪGUMS 19 PÕLAMI REQUEST II.6. APSVEIKUMI, NOVĒLĒJUMI 19 2 VȮNTARMÕMI CONGRATULATIONS, WISHES II.7. DIENAS, MĒNEŠI, GADALAIKI 20 PǞVAD, KŪD, ĀIGASTĀIGAD WEEKDAYS, MONTHS, SEASONS II.8. LAIKA APSTĀKĻI 23 ĀIGA WEATHER II.9. PULKSTENIS 24 KĪELA TIME, TELLING THE TIME _____________________________________________________________________________ III. VĀRDU KRĀJUMS SÕNA VŌLA VOCABULARY __________________________________________________________________ III.1. CILVĒKS 25 RIŠTĪNG PERSON III.2. ĢIMENE 27 AIM FAMILY III.3. MĀJOKLIS 28 KUOD HOME III.4. MĀJLIETAS, APĢĒRBS 29 KUODAŽĀD, ŌRÕND HOUSEHOLD THINGS, CLOTHING III.5. ĒDIENI, DZĒRIENI 31 SĪEMNAIGĀD, JŪOMNAIGĀD MEALS, FOOD, DRINKS III.6. JŪRA, UPE, EZERS 32 MER, JOUG, JŌRA SEA, LAKE, RIVER III.7. -

Same-Sex Relationships: Why Do Many Latvian Politicians Resist Them?

SSE Riga Student Research Papers 2021 : 2 (234) SAME-SEX RELATIONSHIPS: WHY DO MANY LATVIAN POLITICIANS RESIST THEM? Authors: Daniela Gerda Baranova Samanta Mežmale ISSN 1691-4643 ISBN 978-9984-822-58-7 May 2021 Riga Same-Sex Relationships: Why Do Many Latvian Politicians Resist Them? Daniela Gerda Baranova and Samanta Mežmale Supervisor: Xavier Landes May 2021 Riga Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................. 5 Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 7 2. Literature Review .................................................................................................................. 9 2.1. LGBT in the World ......................................................................................................... 9 2.1.1. LGBT Movement ....................................................................................................... 9 2.1.2. Legislation ................................................................................................................ 10 2.1.3. Sexual orientation discrimination and homophobia ................................................. 11 2.1.4. Supporting organisations ......................................................................................... -

International Scholarly Conference the PEREDVIZHNIKI ASSOCIATION of ART EXHIBITIONS. on the 150TH ANNIVERSARY of the FOUNDATION

International scholarly conference THE PEREDVIZHNIKI ASSOCIATION OF ART EXHIBITIONS. ON THE 150TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE FOUNDATION ABSTRACTS 19th May, Wednesday, morning session Tatyana YUDENKOVA State Tretyakov Gallery; Research Institute of Theory and History of Fine Arts of the Russian Academy of Arts, Moscow Peredvizhniki: Between Creative Freedom and Commercial Benefit The fate of Russian art in the second half of the 19th century was inevitably associated with an outstanding artistic phenomenon that went down in the history of Russian culture under the name of Peredvizhniki movement. As the movement took shape and matured, the Peredvizhniki became undisputed leaders in the development of art. They quickly gained the public’s affection and took an important place in Russia’s cultural life. Russian art is deeply indebted to the Peredvizhniki for discovering new themes and subjects, developing critical genre painting, and for their achievements in psychological portrait painting. The Peredvizhniki changed people’s attitude to Russian national landscape, and made them take a fresh look at the course of Russian history. Their critical insight in contemporary events acquired a completely new quality. Touching on painful and challenging top-of-the agenda issues, they did not forget about eternal values, guessing the existential meaning behind everyday details, and seeing archetypal importance in current-day matters. Their best paintings made up the national art school and in many ways contributed to shaping the national identity. The Peredvizhniki -

CLASS Notes Arts and Humanities College Publications

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern CLASS Notes Arts and Humanities College Publications 4-30-2012 CLASS Notes Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/class-notes Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "CLASS Notes" (2012). CLASS Notes. 33. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/class-notes/33 This newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts and Humanities College Publications at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in CLASS Notes by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. April 30, 2012 Welcome to Georgia Southern University / College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Greetings! Time is running out to bid on an eagle in the inaugural flock of the Eagle Nation on Parade public art project. The auction of the first flock of eagles closes May 4; make sure you don't miss out on this opportunity to own one of the three inaugural eagles "Stateboro Blues," "Farmer's Market," or "GATA." You can show your support for the project by making a bid for an eagle at EagleNationOnParade.com. We will install the eagles at the winning bidders' locations of choice where they will stand for many years as beautiful works of art and a testament to Georgia Southern pride. The second flock of eagles will be available for purchase in fall 2013. We will soon issue another statewide call for artists and will be seeking commissioning and seed sponsors for the next round of sculptures. -

Latvia Towards Europe: Internal Security Issues

North Atlantic Treaty Organization Andris Runcis LATVIA TOWARDS EUROPE: INTERNAL SECURITY ISSUES Final Report The preparation of this Report was made possible through a NATO Award. Rîga, 1999 1 Content Introduction 3 1. The basic aspects of a country’s security 5 2. Latvia’s security concept 8 3. Corruption 10 4. Unemployment 17 5. Non-governmental organizations 19 6. The Latvian banking system and its crisis 27 7. Citizenship issue 32 Conclusion 46 Appendix 48 2 Introduction The security of small countries has been a difficult problem since ancient times. Now, when the Cold War has ended and Europe has moved from a bipolar to a multipolar system, when the communist system in Eastern Europe has collapsed and the Soviet empire has disintegrated – processes which have led to the appearance of a series of new and mostly small countries in Europe – we are witnessing a renaissance of small countries in the international arena. Since regaining independence Latvia’s general foreign policy orientation has been associated with integration into European economic, political and military structures where full membership in the European Union (EU) is the cornerstone. The issue has been one of the most consolidated and undisputed on the country’s political agenda. Latvian politicians have stressed the country’s wish to become a member state of the European Union. On October 14, 1995, all political parties represented in the Parliament supported the State President’s proposed Declaration on the Policy of Latvian Integration in the European Union. On October 27, Latvia submitted its application for membership to the EU. -

Representations of Holiness and the Sacred in Latvian Folklore and Folk Belief1

No 6 FORUM FOR ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURE 144 Svetlana Ryzhakova Representations of Holiness and the Sacred in Latvian Folklore and Folk Belief1 In fond memory of my teacher, Vladimir Nikolaevich Toporov The term svēts, meaning ‘holy, sacred’ and its derivatives svētums (‘holiness’, ‘shrine/sacred place’), svētība (‘blessing’, ‘paradise’), svētlaime (‘bliss’), svētīt (‘to bless’, ‘to celebrate’), and svētīgs (‘blessed’, ‘sacred’) comprise an im- portant lexical and semantic field in the Latvian language. These lexemes are regularly en- countered in even the earliest Latvian texts, beginning in the 16th century,2 and are no less frequent in Baltic hydronomy and toponymy, as well as in folklore and colloquial speech. According to fairly widespread opinion, the lexeme svēts in Latvian is a loanword from the Svetlana Ryzhakova 13th-century Old Church Slavonic word svyat Institute of Ethnology [holy] (OCS — *svēts, svyatoi in middle Russian, and Anthropology from the reconstructible Indo-European of the Russian Academy 3 of Sciences, Moscow *ђ&en-) [Endzeīns, Hauzenberga 1934–46]. 1 This article is based on the work for the research project ‘A Historical Recreation of the Structures of Latvian Ethnic Culture’, supported by grant no. 06-06-80278 from the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, as well as the Programme for Basic Research of the Presidium of the Russian Academy of Sci- ences ‘The Adaptation of Nations and Cultures to Environmental Changes and Social and Anthropo- genic Transformations’ on the theme ‘The Evolution of the Ethnic and Cultural Image of Europe under the Infl uence of Migrational Processes and the Modernisation of Society’. 2 See [CC 1585: 248]; [Enchiridon 1586: 11]; [Mancelius 1638: 90]; [Fürecher II: 469]. -

The Peredvizhniki and West European Art

ROSALIND P. BLAKESLEY "THERE IS SOMETHING THERE ...": THE PEREDVIZHNIKI AND WEST EUROPEAN ART The nature of the dialogue between the Peredvizhniki and West European art has been viewed largely through the prism of modernist concerns. Thus their engagement - or lack of it - with French modern- ist luminaries such as Manet and the Impressionists has been subject to much debate. Such emphasis has eclipsed the suggestive, and often creative, relationship between the Peredvizhniki and West European painters whose practice is seen as either anticipatory of or inimical to the modernist camp - to wit, Andreas Achenbach and his circle in Düsseldorf; artists of the Barbizon school; certain Salon regulars; and various Realist groupings in France, Germany and Victorian Britain.'I My intention herc is to explore the subtle connections between such artists, but not as part of any wider art historical concern to challenge the hegemony of modcrnism, for the position of Russian artists vis-ä- vis Western modernist discoursc - before, during and after the time of the avant-garde - is of ongoing concern. Rather, my aim is to question the still prevalent interpretation of the Peredvizhniki as "national" art- All translations are my own unless otherwise indicated. 1. These parallcls havc not gone unremarked. Alison Hilton, for example, writes: "Aside from the Russian settings, the work of Perov and his colleagues shows the same general concern for rural and urban poverty, alcoholism, prostitution, and other mid-nineteenth-century problems that troubled many European artists and writers." ("Scenes from Life and Contemporary History: Russian Realism of the 1870s- 1 880s," in Gabriel P. -

A Reconstructed Indigenous Religious Tradition in Latvia

religions Article A Reconstructed Indigenous Religious Tradition in Latvia Anita Stasulane Faculty of Humanities, Daugavpils University, Daugavpils LV-5401, Latvia; [email protected] Received: 31 January 2019; Accepted: 11 March 2019; Published: 14 March 2019 Abstract: In the early 20th century, Dievtur¯ıba, a reconstructed form of paganism, laid claim to the status of an indigenous religious tradition in Latvia. Having experienced various changes over the course of the century, Dievtur¯ıba has not disappeared from the Latvian cultural space and gained new manifestations with an increase in attempts to strengthen indigenous identity as a result of the pressures of globalization. This article provides a historical analytical overview about the conditions that have determined the reconstruction of the indigenous Latvian religious tradition in the early 20th century, how its form changed in the late 20th century and the types of new features it has acquired nowadays. The beginnings of the Dievturi movement show how dynamic the relationship has been between indigeneity and nationalism: indigenous, cultural and ethnic roots were put forward as the criteria of authenticity for reconstructed paganism, and they fitted in perfectly with nativist discourse, which is based on the conviction that a nation’s ethnic composition must correspond with the state’s titular nation. With the weakening of the Soviet regime, attempts emerged amongst folklore groups to revive ancient Latvian traditions, including religious rituals as well. Distancing itself from the folk tradition preservation movement, Dievtur¯ıba nowadays nonetheless strives to identify itself as a Latvian lifestyle movement and emphasizes that it represents an ethnic religion which is the people’s spiritual foundation and a part of intangible cultural heritage. -

Baltic Unity Within European Unity – Why Myth, Not Reality?

1 Baltic Unity within European Unity – why Myth, not Reality? In recent years a debate about development of the European Union (EU) has become hugely important. There are diverse views on the direction of federalism, which the President of the European Commission J. M. D. Barroso is passionately promoting: “Let’s not be afraid of the words: we will need to move towards a federation of nation states. This is what we need. This is our political horizon.”1 As a consequence of such ambitious plans, the question of national identity and independence has become crucial. However, less attention has been paid to the problem of regional cooperation and the effects of already existing European integration on it, which is exactly what this report aims at. In mass media one can often hear about an entity called ‘the Baltic States‘. This union of three states Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania has cooperated quite a lot in the two last decades of 20th century, however, now the importance of cooperation seems to be in decline. The Baltic unity in the European unity (i.e. EU) is a myth because of two reasons: passive effect of the integration in the EU, when the European unity indirectly and unintentionally influences the cooperation among the Baltic States, and active effect of the policies of the EU, when they have deliberate impact on the Baltic Unity. Baltic Unity before the EU In order to indicate why Baltic unity is impossible in the context of integrated Europe, it is necessary to recall the common aim of Baltic cooperation before the accession to the European Union.