Malevich's Russian Peasant Paintings During the First Five-Year Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Scholarly Conference the PEREDVIZHNIKI ASSOCIATION of ART EXHIBITIONS. on the 150TH ANNIVERSARY of the FOUNDATION

International scholarly conference THE PEREDVIZHNIKI ASSOCIATION OF ART EXHIBITIONS. ON THE 150TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE FOUNDATION ABSTRACTS 19th May, Wednesday, morning session Tatyana YUDENKOVA State Tretyakov Gallery; Research Institute of Theory and History of Fine Arts of the Russian Academy of Arts, Moscow Peredvizhniki: Between Creative Freedom and Commercial Benefit The fate of Russian art in the second half of the 19th century was inevitably associated with an outstanding artistic phenomenon that went down in the history of Russian culture under the name of Peredvizhniki movement. As the movement took shape and matured, the Peredvizhniki became undisputed leaders in the development of art. They quickly gained the public’s affection and took an important place in Russia’s cultural life. Russian art is deeply indebted to the Peredvizhniki for discovering new themes and subjects, developing critical genre painting, and for their achievements in psychological portrait painting. The Peredvizhniki changed people’s attitude to Russian national landscape, and made them take a fresh look at the course of Russian history. Their critical insight in contemporary events acquired a completely new quality. Touching on painful and challenging top-of-the agenda issues, they did not forget about eternal values, guessing the existential meaning behind everyday details, and seeing archetypal importance in current-day matters. Their best paintings made up the national art school and in many ways contributed to shaping the national identity. The Peredvizhniki -

The Peredvizhniki and West European Art

ROSALIND P. BLAKESLEY "THERE IS SOMETHING THERE ...": THE PEREDVIZHNIKI AND WEST EUROPEAN ART The nature of the dialogue between the Peredvizhniki and West European art has been viewed largely through the prism of modernist concerns. Thus their engagement - or lack of it - with French modern- ist luminaries such as Manet and the Impressionists has been subject to much debate. Such emphasis has eclipsed the suggestive, and often creative, relationship between the Peredvizhniki and West European painters whose practice is seen as either anticipatory of or inimical to the modernist camp - to wit, Andreas Achenbach and his circle in Düsseldorf; artists of the Barbizon school; certain Salon regulars; and various Realist groupings in France, Germany and Victorian Britain.'I My intention herc is to explore the subtle connections between such artists, but not as part of any wider art historical concern to challenge the hegemony of modcrnism, for the position of Russian artists vis-ä- vis Western modernist discoursc - before, during and after the time of the avant-garde - is of ongoing concern. Rather, my aim is to question the still prevalent interpretation of the Peredvizhniki as "national" art- All translations are my own unless otherwise indicated. 1. These parallcls havc not gone unremarked. Alison Hilton, for example, writes: "Aside from the Russian settings, the work of Perov and his colleagues shows the same general concern for rural and urban poverty, alcoholism, prostitution, and other mid-nineteenth-century problems that troubled many European artists and writers." ("Scenes from Life and Contemporary History: Russian Realism of the 1870s- 1 880s," in Gabriel P. -

Russian Art on the Rise

H-Announce Russian Art on the Rise Announcement published by Isabel Wünsche on Wednesday, March 29, 2017 Type: Call for Papers Date: May 15, 2017 Location: Germany Subject Fields: Art, Art History & Visual Studies, Cultural History / Studies, Fine Arts, Humanities, Russian or Soviet History / Studies CfP: Russian Art on the Rise 5th Graduate Workshop of the Russian Art & Culture Group Berlin, September 22–23, 2017 Working languages: English and German | Arbeitssprachen: Englisch und Deutsch Deadline for submission: May 15, 2017 The fifth graduate workshop of the Russian Art and Culture Group will focus on the theorization and contextualization of Russian art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries by its contemporaries, positioning it in the cultural discourses of the period that ranged from national appreciation to scientific approaches. Thanks to the collaboration of Jacobs University Bremen and Freie Universität Berlin, the workshop will take place in Berlin for the first time. The workshop will examine the development of Russian art during the period from 1870 to the 1920s. Questioning the self-imposed requirements for their creative work, artistic movements such as the Peredvizhniki and Mir iskusstva addressed subjects specific to Russian culture. The artists not only strove to capture a Russian cultural identity in their works but utilized folk art and crafts to establish a specific Russian style. Modernist artistic styles of western European origin, e.g. French impressionism, were well received by Russian artists. Furthermore, the Russian avant-garde proclaimed a pure form of painting free from historical or literary context and the forms of nature. In this process, new academies were created, their aim was to establish a scientific approach to art and to research various artistic Citation: Isabel Wünsche. -

Abstract Vladimir Makovsky

ABSTRACT VLADIMIR MAKOVSKY: THE POLITICS OF NINETEENTH-CENTURY RUSSIAN REALISM Tessa J. Crist, M.A. School of Art and Design Northern Illinois University, 2015 Barbara Jaffee, Director This thesis examines the political work produced by a little-known Russian Realist, Vladimir Makovsky (1846-1920), while he was a member of the nineteenth-century art collective Peredvizhniki. Increasingly recognized for subtle yet insistent opposition to the tsarist regime and the depiction of class distinctions, the work of the Peredvizhniki was for decades ignored by modernist art history as the result of an influential article, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” written by American art critic Clement Greenberg in 1939. In this article, Greenberg suggests the work of Ilya Repin, the most renowned member of the Peredvizhniki, should be regarded not as art, but as “kitsch”--the industrialized mass culture of an urban working class. Even now, scholars who study the Peredvizhniki concern themselves with the social history of the group as a whole, rather than with the merits of specific artworks. Taking a different approach to analyzing the significance of the Peredvizhniki and of Makovsky specifically this thesis harnesses the powerful methodologies devised in the 1970s by art historians T.J. Clark and Michael Fried, two scholars who are largely responsible for reopening the dialogue on the meaning and significance of Realism in the history of modern art. NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DE KALB, ILLINOIS MAY 2015 VLADIMIR MAKOVSKY: THE POLITICS OF NINETEENTH-CENTURY RUSSIAN REALISM BY TESSA J. CRIST ©2015 Tessa J. Crist A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTERS OF ARTS SCHOOL OF ART AND DESIGN Thesis Director: Barbara Jaffee TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................... -

Some Highlights of Russian Realism from the Golden Age Awarded an Honorary Professorship by Provincial Cities, Not Just St

FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE By Melville Holmes In 1863, the same year that disaffection with the Paris Salon reached such a pitch that Napoleon III felt obliged to mount the Salon des Refusés, concurrent with the offcial Salon, a minor insurrection took place in the Imperial Academy in St. Petersburg, but one that would go down in the annals of Russian culture as a turning point and a milestone in the history of Russian art. A group of art students at the Academy, largely led by Kramskoi, refused to take part in a competition for a gold medal, which included the prize of a scholarship to study abroad, in Paris or Italy. The reason given had to do with certain rules of the contest and wanting the freedom to select one’s own subject matter. This was the frst time the students stood up to the authorities, though the real upshot was rather indefnite. Eight of the rebels would go on to become offcially acknowledged Academicians, including Kramskoi. In fact, the Russian Academy seems largely to have been much more kindly and encouraging to gifted artists Vasili Pukirev (1832-1890) From with fresh ideas than their Parisian The Unequal Marriage 1862 counterparts. oil on canvas 68.5 х 54” One example is Vasili Pukirev (1832- Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow 1890), best known for The Unequal The fgure on the far right is thought to be Pukirev. Marriage. There were lots of scenes of daily, often peasant life (“genre” paintings), being done at the time but they weren’t wandering or traveling infuential critic Vladimir Stasov this representation of a marriage between artists. -

The Institute of Modern Russian Culture at Blue Lagoon

THE INSTITUTE OF MODERN RUSSIAN CULTURE AT BLUE LAGOON NEWSLETTER No. 77, February, 2019 IMRC, Mail Code 4353, USC, Los Angeles, Ca, 90089-4353 USA Tel. : (213) 740-2735 Fax: 740-8550 E: [email protected] website: https://dornsife.usc.edu/sll/imrc STATUS This is the seventy-seventh biannual Newsletter of the IMRC and follows the last issue which appeared in August, 2018. The information presented here relates primarily to events connected with the IMRC during the spring and summer of 2018. For the benefit of new readers, data on the present structure of the IMRC are given on the last page of this issue. IMRC Newsletters for 1979-2018 are available electronically and can be requested via e-mail at [email protected]. All IMRC newsletters are available on University of Cincinnatii's institutional repository, Scholar@UC (https://scholar.uc.edu). RUSSIA: Оurs is the Victory One of the most prominent leit-motifs in everyday Moscow life is the word, concept, and metaphor of “victory” (pobeda) and its analogy “triumph”. Of course, Moscow has engineered many conquests, from the rout of Napoleon in 1812 to the rout of Hitler in 1943, but, even so, the persistence and application of “victory” is so striking that its continued omnipresence might well inspire the following scenario: After arriving on Victory Airlines on 9 May (Victory Day), I checked into the Hotel Victory not far from the Victory of Taste Supermarket adjacent to Triumphal Street downtown. Taking a Victory ‘Bus to the nearby Victory Café, I ordered a Victory Salad and a slice of Victory Cake out of their Victory refrigerator. -

1 Life Between Two Panels Soviet Nonconformism in the Cold War Era

Life Between Two Panels Soviet Nonconformism in the Cold War Era DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Clinton J. Buhler, M.A. Graduate Program in History of Art * * * * * The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Myroslava M. Mudrak, Advisor Dr. Kris Paulsen Dr. Jessie Labov Dr. Aron Vinegar 1 Copyright by Clinton J. Buhler 2013 2 Abstract Beneath the façade of total conformity in the Soviet Union, a dynamic underground community of artists and intellectuals worked in forced isolation. Rejecting the mandates of state-sanctioned Socialist Realist art, these dissident artists pursued diverse creative directions in their private practice. When they attempted to display their work publicly in 1974, the carefully crafted façade of Soviet society cracked, and the West became aware of a politically subversive undercurrent in Soviet cultural life. Responding to the international condemnation of the censorship, Soviet officials allowed and encouraged the emigration of the nonconformist artists to the West. This dissertation analyzes the foundation and growth of the nonconformist artistic movement in the Soviet Union, focusing on a key group of artists who reached artistic maturity in the Brezhnev era and began forging connections in the West. The first two chapters of the dissertation center on works that were, by and large, produced before emigration to the West. In particular, I explore the growing awareness of artists like Oleg Vassiliev of their native artistic heritage, especially the work of Russian avant-garde artists like Kazimir Malevich. I look at how Vassiliev, in a search for an alternative form of expression to the mandated form of art, took up the legacy of nineteenth-century Realism, avant-garde abstraction, and Socialist Realism. -

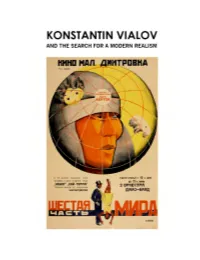

Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph

Aleksandr Deineka, Portrait of the artist K.A. Vialov, 1942. Oil on canvas. National Museum “Kyiv Art Gallery,” Kyiv, Ukraine Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. D. Edited by Brian Droitcour Design and production by Jolie Simpson Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Research Assistant: Elena Emelyanova, Research Curator, Rare Books Department, Russian State Library, Moscow Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2018 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2018 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Poster for Dziga Vertov’s Film Shestaia chast’ mira (A Sixth Part of the World), 1926. Lithograph, 42 1/2 x 28 1/4” (107.9 x 71.7 cm) Plate XVII Note on transliteration: For this catalogue we have generally adopted the system of transliteration employed by the Library of Congress. However, for the names of artists, we have combined two methods. For their names according to the Library of Congress system even when more conventional English versions exist: e.g. , Aleksandr Rodchenko, not Alexander Rodchenko; Aleksandr Deineka, not Alexander Deineka; Vasilii Kandinsky, not Wassily Kandinsky. Surnames with an “-ii” ending are rendered with an ending of “-y.” But in the case of artists who emigrated to the West, we have used the spelling that the artist adopted or that has gained common usage. Soft signs are not used in artists’ names but are retained elsewhere. TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 - ‘A Glimpse of Tomorrow’: Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. -

The University of Chicago Kazimir Malevich And

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO KAZIMIR MALEVICH AND RUSSIAN MODERNISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY BY DANIEL KALMAN PHILLIPS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Daniel Kalman Phillips All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................. viii ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................x INTRODUCTION MALEVICH, ART, AND HISTORY .......................................................................1 CHAPTER ONE MODERNISMS BEFORE SUPREMATISM........................................................18 CHAPTER TWO AN ARTIST OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY ...............................................71 CHAPTER THREE SUPREMATISM IN 1915 ...................................................................................120 CHAPTER FOUR CODA: SUPREMATISMS AFTER SUPREMATISM .......................................177 WORKS CITED................................................................................................. 211 iii LIST OF FIGURES1 0.1 Kazimir Malevich, Black Square, 1915. 0.2 Kazimir Malevich, [Airplane Flying], 1915. 0.3 John Baldessari, Violent Space Series: Two Stares Making a Point but Blocked by a Plane (for Malevich), 1976. 0.4 Yves Klein, -

Download the Paper

Permanent Secretariat Av. Drassanes, 6-8, planta 21 08001 Barcelona Tel. + 34 93 256 25 09 Fax. + 34 93 412 34 92 Strand 1: Art Nouveau Cities: between cosmopolitanism and local tradition Art Nouveau inLate Imperial Russia: Cosmopolitanism, Europeanization and “National Revival” in the Art Periodical the World of Art (Mir Iskusstva, 1898-1904) byHanna Chuchvaha, University of Alberta (Canada) Art Nouveau was launched in Europe in the early 1890s; several years after it penetrated late Imperial Russia and became legitimated there in various art forms in the first decade of the twentieth century. Serge Diaghilev was one of those art entrepreneurs, who “imported” the visual language of European Art Nouveau.He organized his famous exhibits in the late 1890s after his grand tour to Europe and showed in Russia the contemporary artworks by European artists Giovanni Boldini, Frank Brangwyn, Charles Conder, Max Lieberman, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Gustave Moreau, Lucien Simon, EugèneCarrière, Jean-Louis Forain, Edgar Degas, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes and others. However, despite their novelty and European acknowledgement, Diaghilev‟s art showswere not easily accepted by the public and established art critics.Moreover, the contemporary Russian art presented at the shows, which reflected new European tendenciesand influence, was heavily criticized.The critics consideredthe new Russian art harmful and “decadent”and proclaimed the “national revival” and Realism as the only right direction for the visual arts. Nevertheless, Art Nouveau gradually became a part of Russian visual culture of the early twentieth century and was employed in architecture, sculpture, painting, interior design and the graphic arts. Elena Chernevich and Mikhail Anikst claim that in Russian graphic design Art Nouveau took hold only after 19001.It can be acclaimed as true, but only in regards tothe direct“quotations” of “imported” European Art Nouveau features such as curvilinear forms and twisting lines, and use of shapes of nature, such as roots and plant stems and flowers for inspiration. -

Art and Commerce in Late Imperial Russia: the Peredvizhniki, a Partnership of Artists'

H-SHERA Olsen on Shabanov, 'Art and Commerce in Late Imperial Russia: The Peredvizhniki, a Partnership of Artists' Review published on Monday, April 20, 2020 Andrey Shabanov. Art and Commerce in Late Imperial Russia: The Peredvizhniki, a Partnership of Artists. New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2019. Illustrations. 280 pp. $108.00 (e-book), ISBN 978-1-5013-3553-2; $120.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-5013-3552-5. Reviewed by Trenton Olsen (Ohio State University)Published on H-SHERA (April, 2020) Commissioned by Hanna Chuchvaha (University of Calgary) Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=54485 For nearly a century, scholarship regarding the Peredvizhniki misconstrued the group’s true character. Stalinist historians were primarily responsible as they politicized the group, fashioning them as the forefathers of socialist realism. In his introduction, Andrey Shabanov cites the work of two modern scholars who have helped reverse this reading. Pioneering efforts were made by Elizabeth Valkenier in her work Russian Realist Art: The State and Society; The Peredvizhniki and Their Tradition (1977) to wrest the legacy of the group away from its propagandistic historiography, and David Jackson’s more recent monograph, The Wanderers and Critical Realism in Nineteenth- Century Russian Painting (2006), likewise provides fresh understanding of these artists and their work. Despite the revisionary efforts of scholars over the last several decades, Shabanov takes aim at a recurring myth surrounding the Wanderers—namely, to dispel the conceptualization of the Peredvizhniki as a group of realists with a homogenous aesthetic and ideology. He suggests the root of this mischaracterization began with period art criticism offered by figures like Vladimir Stasov, but its pervasiveness has colored most scholarship on the artists to the present. -

Internal and External Enemies

4. Internal and External Enemies The Cold War The Cold War was a struggle between two great powers that wanted to mold the world according to their principles. Although a direct military confrontation was avoided, both camps were heavily engaged in a symbolic competition. Accomplishments in the fijields of production and consump- tion, social security, technology, scientifijic discoveries, sports and culture were celebrated as proof of ideological superiority. The visual arts were part of this rivalry, and they caused a lot of confusion. At fijirst, the artistic borders between East and West were as rigorously defijined as in the Third Reich. Socialist Realism, aimed at convincing the viewer of the blessings of Socialism and the eternal wisdom of the communist party, defijined the visual culture of the Soviet Union and its satellite states, beginning during Stalin’s times. In the 1950s, modernism became the dominant art form in the West, mostly defijined in strictly aesthetic, non-political terms. Paradoxically, this ‘pure’ art was confronted with the propagandistic realism of both the Eastern bloc and the Third Reich as a sign of political freedom in the Western world. On the other hand, precisely the lack of recognizable political and social engagement in modern art became a target for communist critics, who rejected this art as noth- ing but noncommittal decoration, a typical expression of a bourgeois-decadent society. Nonetheless, once again, reality was less straightforward than it might seem. During the years directly following the October Revolution, modern art was very successful 61 in communist Russia, while in the United States it did not make much headway until the 1930s.