Azu Etd Mr20090029 Sip1 M.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Art Implementation Plan

City of Alexandria Office of the Arts & the Alexandria Commission for the Arts An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy Submitted by Todd W. Bressi / Urban Design • Place Planning • Public Art Meridith C. McKinley / Via Partnership Elisabeth Lardner / Lardner/Klein Landscape Architecture Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Vision, Mission, Goals 3.0 Creative Directions Time and Place Neighborhood Identity Urban and Natural Systems 4.0 Project Development CIP-related projects Public Art in Planning and Development Special Initiatives 5.0 Implementation: Policies and Plans Public Art Policy Public Art Implementation Plan Annual Workplan Public Art Project Plans Conservation Plan 6.0 Implementation: Processes How the City Commissions Public Art Artist Identification and Selection Processes Public Art in Private Development Public Art in Planning Processes Donations and Memorial Artworks Community Engagement Evaluation 7.0 Roles and Responsibilities Office of the Arts Commission for the Arts Public Art Workplan Task Force Public Art Project Task Force Art in Private Development Task Force City Council 8.0 Administration Staffing Funding Recruiting and Appointing Task Force Members Conservation and Inventory An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy 2 Appendices A1 Summary Chart of Public Art Planning and Project Development Process A2 Summary Chart of Public Art in Private Development Process A3 Public Art Policy A4 Survey Findings and Analysis An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy 3 1.0 Introduction The City of Alexandria’s Public Art Policy, approved by the City Council in October 2012, was a milestone for public art in Alexandria. That policy, for the first time, established a framework for both the City and private developers to fund new public art projects. -

Public Art Toolkit

Aylesbury Vale Public Art Toolkit Who is this toolkit for? This toolkit can be used by anyone involved with making public art projects happen, however it has been developed to be specifically relevant to people commissioning art within a local authority context. What is public art? Public art has long been a feature of the public spaces across our towns and cities, with sculptures, paintings and murals often recalling historical characters or commemorating important events. Today, public art and artists are increasingly being placed at the centre of regeneration schemes as developers and local authorities recognise the benefits of integrating artworks into such programmes. Public art can include a variety of artistic approaches whereby artists or craftspeople work within the public realm in urban, rural or natural environments. Good public art seeks to integrate the creative skills of artists into the processes that shape the environments we live in. I see what you mean (2008), Lawrence Argent, University of Denver, USA For the Gentle Wind Doth Move Silently, Invisibly, (2006), Brian Tolle, Clevland, USA Spiral, Rick Kirby, (2004), South Woodham Ferres, Essex Animikii - Flies the Thunder, Anne Allardyce, (1992), Thunder Bay, Canada Types of Public Art approaches When thinking about future public art projects it is important to consider the full range of artistic approaches that could be used in a particular site, public art can be permanent or temporary; the following categories summarise popular approaches to public art. Sculpture Sculptural works are not solely about creating a precious piece of art but creating a piece which extends the sculpture into the wider landscape linking it with the environment and focussing attention on what is already there. -

Malevich's Russian Peasant Paintings During the First Five-Year Plan

The NEP Era: Soviet Russia 1921-1928, 8 (2014), 1-24. ARTICLES / СТАТЬИ MARIE GASPER-HULVAT Proletarian Credibility? Malevich’s Russian Peasant Paintings during the First Five-Year Plan During the years immediately before and after the 1917 October Revo- lution, the prominent Avant-Garde artist Kazimir Malevich (1878-1935) enjoyed renown in Russian art circles for his signature, abstract work. His nonobjective “Suprematist” style constituted one of the first models of purely abstract, non-representational painting in the modernist tradition of Western art. If the primary subject matter that Malevich’s work was con- cerned with is geometric forms, the second most recognizable content of Malevich’s paintings would be the Russian peasant. Not all of his work was abstract, and those paintings which do represent identifiable imagery have a notable tendency to favor rural subject matter, both landscapes and their inhabitants. In fact, Malevich began his career as a painter depicting peasant figures, prior to developing his signature style of abstraction in 1915. After his purely abstract period concluded in the mid-1920s, similar peasant themes reemerged in his work at the turn of the 1930s.1 While peasant imagery from early in Malevich’s career largely reflects the concerns of a young artist grappling with West European art historical precedents adapted to a Slavic context, I contend that his later peasant works engaged with the complex set of historical and political circum- stances of the early Stalinist era. Other scholars have explained how the artist’s motivations for creating the later peasant works were multifaceted and related significantly to his philosophical treatises regarding the essen- tial nature of art and humanity.2 Another set of scholars has read these images as reactions to contemporary political events.3 1. -

Photo/Arts MY DEAR MALEVICH (MDM)

TOM R. CHAMBERS - Photo/Arts Highlights from his personal website. Many of the links on the page go back to the website for greater detailing. Tom R. Chambers is a documentary photographer and visual artist, and he is currently working with the pixel as Minimalist Art ("Pixelscapes") and Kazimir Malevich's "Black Square" ("Black Square Interpretations"). He has over 100 exhibitions to his credit. His "My Dear Malevich" project has received international acclaim, and it was shown as a part of the "Suprematism Infinity: Reflections, Interpretations, Explorations" exhibition in conjunction with the "100 Years of Suprematism" conference at Columbia University, New York City (2015). MY DEAR MALEVICH (MDM) "My Dear Malevich" This homage to Kazimir Malevich is a confirmation of Tom R. Chambers' Pixelscapes as Minimalist Art and in keeping with Malevich's Suprematism - the feeling of non-objectivity - the creation of a sense of bliss and wonder via abstraction. Chambers' action of looking within a portrait (photo) of Kazimir Malevich to find the basic component(s), pixel(s) is the same action as Malevich looking within himself - inside the objective world - for a pure feeling in creative art to find his "Black Square", "Black Cross" and other Suprematist works. And there's a mathematical parallel between Malevich's primitive square ("Black Square") ... divided into four, then divided into nine ("Black Cross") ... and Chambers' Pixelscapes. The pixel is the most basic component of any computer graphic, and it can be represented by 1 bit (a 1 if the pixel is black, or a 0 if the pixel is white). And filters (tools [e.g., halftone]) in a graphics program like Photoshop produce changes by mathematically modifying pixel values based on the values of neighboring pixels. -

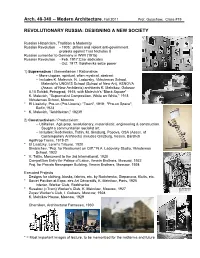

C:\Users\Kai\Documents\CMU Teaching\Modern\Handouts

Arch. 48-340 -- Modern Architecture, Fall 2011 Prof. Gutschow, Class #19 REVOLUTIONARY RUSSIA: DESIGNING A NEW SOCIETY Russian Historicism, Tradition & Modernity Russian Revolution - 1905: strikes and violent anti-government protests against Tsar Nicholas II Russian surrender to Germany in WWI (1915) Russian Revolution - Feb. 1917:Czar abdicates - Oct. 1917: Bolsheviks seize power 1) Suprematism / Elementarism / Rationalism -- More utopian, spiritual, often mystical, abstract -- Includes K. Malevich, N. Ladovsky, Vkhutemas School, Malevich's UNOVIS School (School of New Art), ASNOVA (Assoc. of New Architects) architects K. Melnikov, Golosov 0.10 Exhibit, Petrograd, 1915, with Malevich’s “Black Square” K. Malevich, "Suprematist Composition, White on White," 1918 Vkhutemas School, Moscow * El Lissitzky, Pro-un (Pro-Unovis): "Town", 1919; "Pro-un Space", Berlin,1923 * K. Malevich, "Arkhitekton," 1923ff 2) Constructivism / Productivism: -- Utilitarian, Agit-prop, revolutionary, materialistic, engineering & construction. Sought a communitarian socialist art. -- Includes: Rodchenko, Tatlin, M. Ginsburg, Popova, OSA (Assoc. of Contemporary Architects) includes Ginzburg, Vesnin, Barshch AgitProp Trains, 1919-21 * El Lissitzky, Lenin's Tribune, 1920 Simbirchev, “Proj. for Restaurant on Cliff," N.A. Ladovsky Studio, Vkhutemas School, 1922 * V. Tatlin, Monument to the 3rd International, 1920 Competition Entry for Palace of Labor, Vesnin Brothers, Moscow, 1922 Proj. for Pravda Newspaper Building, Vesnin Brothers, Moscow, 1924 Executed Projects Designs for clothing, kiosks, fabrics, etc. by Rodchenko, Stepanova, Klutis, etc. * Soviet Pavilion at Expo. des Art Décoratifs, K. Melnikov, Paris, 1925 Interior, Worker Club, Rodchenko * Rusakov (=Tram) Worker's Club, K. Melnikov, Moscow, 1927 Zuyev Worker's Club, I. Golosov, Moscow, 1928 K. Melnikov House, Moscow, 1929 Chernikov, Architectural Fantasies, 1930 * = Most important images of lecture, to be memorized for the midterms and future . -

GREEN PAPER Page 1

AMERICANS FOR THE ARTS PUBLIC ART NETWORK COUNCIL: GREEN PAPER page 1 Why Public Art Matters Cities gain value through public art – cultural, social, and economic value. Public art is a distinguishing part of our public history and our evolving culture. It reflects and reveals our society, adds meaning to our cities and uniqueness to our communities. Public art humanizes the built environment and invigorates public spaces. It provides an intersection between past, present and future, between disciplines, and between ideas. Public art is freely accessible. Cultural Value and Community Identity American cities and towns aspire to be places where people want to live and want to visit. Having a particular community identity, especially in terms of what our towns look like, is becoming even more important in a world where everyplace tends to looks like everyplace else. Places with strong public art expressions break the trend of blandness and sameness, and give communities a stronger sense of place and identity. When we think about memorable places, we think about their icons – consider the St. Louis Arch, the totem poles of Vancouver, the heads at Easter Island. All of these were the work of creative people who captured the spirit and atmosphere of their cultural milieu. Absent public art, we would be absent our human identities. The Artist as Contributor to Cultural Value Public art brings artists and their creative vision into the civic decision making process. In addition the aesthetic benefits of having works of art in public places, artists can make valuable contributions when they are included in the mix of planners, engineers, designers, elected officials, and community stakeholders who are involved in planning public spaces and amenities. -

Read Book Kazimir Malevich

KAZIMIR MALEVICH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Achim Borchardt-Hume | 264 pages | 21 Apr 2015 | TATE PUBLISHING | 9781849761468 | English | London, United Kingdom Kazimir Malevich PDF Book From the beginning of the s, modern art was falling out of favor with the new government of Joseph Stalin. Red Cavalry Riding. Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students. The movement did have a handful of supporters amongst the Russian avant garde but it was dwarfed by its sibling constructivism whose manifesto harmonized better with the ideological sentiments of the revolutionary communist government during the early days of Soviet Union. What's more, as the writers and abstract pundits were occupied with what constituted writing, Malevich came to be interested by the quest for workmanship's barest basics. Black Square. Woman Torso. The painting's quality has degraded considerably since it was drawn. Guggenheim —an early and passionate collector of the Russian avant-garde—was inspired by the same aesthetic ideals and spiritual quest that exemplified Malevich's art. Hidden categories: Articles with short description Short description matches Wikidata Use dmy dates from May All articles with unsourced statements Articles with unsourced statements from June Lyubov Popova - You might like Left Right. Harvard doctoral candidate Julia Bekman Chadaga writes: "In his later writings, Malevich defined the 'additional element' as the quality of any new visual environment bringing about a change in perception Retrieved 6 July A white cube decorated with a black square was placed on his tomb. It was one of the most radical improvements in dynamic workmanship. Landscape with a White House. -

International Scholarly Conference the PEREDVIZHNIKI ASSOCIATION of ART EXHIBITIONS. on the 150TH ANNIVERSARY of the FOUNDATION

International scholarly conference THE PEREDVIZHNIKI ASSOCIATION OF ART EXHIBITIONS. ON THE 150TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE FOUNDATION ABSTRACTS 19th May, Wednesday, morning session Tatyana YUDENKOVA State Tretyakov Gallery; Research Institute of Theory and History of Fine Arts of the Russian Academy of Arts, Moscow Peredvizhniki: Between Creative Freedom and Commercial Benefit The fate of Russian art in the second half of the 19th century was inevitably associated with an outstanding artistic phenomenon that went down in the history of Russian culture under the name of Peredvizhniki movement. As the movement took shape and matured, the Peredvizhniki became undisputed leaders in the development of art. They quickly gained the public’s affection and took an important place in Russia’s cultural life. Russian art is deeply indebted to the Peredvizhniki for discovering new themes and subjects, developing critical genre painting, and for their achievements in psychological portrait painting. The Peredvizhniki changed people’s attitude to Russian national landscape, and made them take a fresh look at the course of Russian history. Their critical insight in contemporary events acquired a completely new quality. Touching on painful and challenging top-of-the agenda issues, they did not forget about eternal values, guessing the existential meaning behind everyday details, and seeing archetypal importance in current-day matters. Their best paintings made up the national art school and in many ways contributed to shaping the national identity. The Peredvizhniki -

What Is Public Art?

POLICIES & PROCEDURES MANUAL Updated: February 2015 Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 4 What is Public Art? ................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 CITY-FUNDED PUBLIC ART ............................................................................................................... 5 Summary of the Process .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Funding Policies ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Funding Procedures ................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Public Art Manager’s Role ..................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Generating Ideas for Public Art in Capital Projects............................................................................................................................. 8 Methods of Selecting Public Art .......................................................................................................................................................... -

10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art

Article 26 10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art 1. It’s public! Everyone has access to public art. It’s directly in the public sphere and not confined to galleries or museums. 2. It enriches our physical environments, bringing streetscapes, plazas, town buildings and schools to life. 3. It’s a great tool for civic engagement, building social capital and encouraging civil discourse. 4. It provides professional opportunities for artists and cultivates an environment in which the creative class thrives. 5. It boosts local economies. Businesses supply materials and labor; restaurants, hotels and transportation companies benefit from a site that attracts visitors. 6. It’s an investment in place making—measured by livability and quality of life—that also engenders community pride. 7. It connects citizens to their neighbors and their shared history through documentation and celebration, and makes cultural heritage a tangible community asset. 8. It enlivens places where people work, which can improve employee morale, productivity and respect. 9. It creates supportive learning environments. It opens eyes—and minds! It attracts students to environments conducive to both learning and fun. 10. It raises public awareness about important community issues, such as environmental stewardship and respect for diversity. --From the Amherst Public Art Commission and the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. The Amherst Public Art Commission Why Public Art for Amherst? Public art adds enormous value to the cultural, aesthetic and economic vitality of a community. It is now a well-accepted principle of urban design that public art contributes to a community’s identity, fosters community pride and a sense of belonging, and enhances the quality of life for its residents and visitors. -

The Peredvizhniki and West European Art

ROSALIND P. BLAKESLEY "THERE IS SOMETHING THERE ...": THE PEREDVIZHNIKI AND WEST EUROPEAN ART The nature of the dialogue between the Peredvizhniki and West European art has been viewed largely through the prism of modernist concerns. Thus their engagement - or lack of it - with French modern- ist luminaries such as Manet and the Impressionists has been subject to much debate. Such emphasis has eclipsed the suggestive, and often creative, relationship between the Peredvizhniki and West European painters whose practice is seen as either anticipatory of or inimical to the modernist camp - to wit, Andreas Achenbach and his circle in Düsseldorf; artists of the Barbizon school; certain Salon regulars; and various Realist groupings in France, Germany and Victorian Britain.'I My intention herc is to explore the subtle connections between such artists, but not as part of any wider art historical concern to challenge the hegemony of modcrnism, for the position of Russian artists vis-ä- vis Western modernist discoursc - before, during and after the time of the avant-garde - is of ongoing concern. Rather, my aim is to question the still prevalent interpretation of the Peredvizhniki as "national" art- All translations are my own unless otherwise indicated. 1. These parallcls havc not gone unremarked. Alison Hilton, for example, writes: "Aside from the Russian settings, the work of Perov and his colleagues shows the same general concern for rural and urban poverty, alcoholism, prostitution, and other mid-nineteenth-century problems that troubled many European artists and writers." ("Scenes from Life and Contemporary History: Russian Realism of the 1870s- 1 880s," in Gabriel P. -

Digital Suprematism Overview

DIGITAL SUPREMATISM "Tom R. Chambers is a Texan with a “Russian, Suprematist soul”. He has repeatedly introduced the modern trend of new media art to the masses. He has brought Minimalism to the pixel. In 2000, Chambers began to look at the pixel in the context of Abstraction and Minimalism. And he is currently working with interpretations of Kazimir Malevich’s “Black Square” and other Suprematist forms. His work calls our attention to visual singularity, which is all that we see in the digital universe. Since the pixel corresponds to what we call “subatomic particles” in our physical universe, Chambers’ work connects us directly with the feeling of Russian Suprematism, described as the spirit that pervades everything, and pays tribute to the faith in the ability of abstraction to convey “net feeling in the work.” (Curator, OMG [One Month Gallery], Moscow, Russia, 2015) Chambers states: “I have always liked Minimalist works and as a digital artist, I began to explore the pixel as an art form in 2000. As I did research, and experimented with this picture element, I also began to read about Kazimir Malevich and his extreme Minimalist approach with ‘Black Square’. The more I contemplated his ‘Black Square’, the deeper I moved into the pixel and consequently the creation of the ‘My Dear Malevich’ project, which revealed similar to identical Suprematist forms that he created. I have focused on the pixel and his ‘Black Square’ ever since.” My Dear Malevich (MDM) (http://tomrchambers.com/malevich.html) In 2007, Chambers traveled (via magnification) into a digitized photograph of Malevich and discovered at the singular pixel level arrangements which echo back directly to Malevich's own totally abstract compositions.