Resource What Is Public Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Art Implementation Plan

City of Alexandria Office of the Arts & the Alexandria Commission for the Arts An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy Submitted by Todd W. Bressi / Urban Design • Place Planning • Public Art Meridith C. McKinley / Via Partnership Elisabeth Lardner / Lardner/Klein Landscape Architecture Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Vision, Mission, Goals 3.0 Creative Directions Time and Place Neighborhood Identity Urban and Natural Systems 4.0 Project Development CIP-related projects Public Art in Planning and Development Special Initiatives 5.0 Implementation: Policies and Plans Public Art Policy Public Art Implementation Plan Annual Workplan Public Art Project Plans Conservation Plan 6.0 Implementation: Processes How the City Commissions Public Art Artist Identification and Selection Processes Public Art in Private Development Public Art in Planning Processes Donations and Memorial Artworks Community Engagement Evaluation 7.0 Roles and Responsibilities Office of the Arts Commission for the Arts Public Art Workplan Task Force Public Art Project Task Force Art in Private Development Task Force City Council 8.0 Administration Staffing Funding Recruiting and Appointing Task Force Members Conservation and Inventory An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy 2 Appendices A1 Summary Chart of Public Art Planning and Project Development Process A2 Summary Chart of Public Art in Private Development Process A3 Public Art Policy A4 Survey Findings and Analysis An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy 3 1.0 Introduction The City of Alexandria’s Public Art Policy, approved by the City Council in October 2012, was a milestone for public art in Alexandria. That policy, for the first time, established a framework for both the City and private developers to fund new public art projects. -

Public Art Toolkit

Aylesbury Vale Public Art Toolkit Who is this toolkit for? This toolkit can be used by anyone involved with making public art projects happen, however it has been developed to be specifically relevant to people commissioning art within a local authority context. What is public art? Public art has long been a feature of the public spaces across our towns and cities, with sculptures, paintings and murals often recalling historical characters or commemorating important events. Today, public art and artists are increasingly being placed at the centre of regeneration schemes as developers and local authorities recognise the benefits of integrating artworks into such programmes. Public art can include a variety of artistic approaches whereby artists or craftspeople work within the public realm in urban, rural or natural environments. Good public art seeks to integrate the creative skills of artists into the processes that shape the environments we live in. I see what you mean (2008), Lawrence Argent, University of Denver, USA For the Gentle Wind Doth Move Silently, Invisibly, (2006), Brian Tolle, Clevland, USA Spiral, Rick Kirby, (2004), South Woodham Ferres, Essex Animikii - Flies the Thunder, Anne Allardyce, (1992), Thunder Bay, Canada Types of Public Art approaches When thinking about future public art projects it is important to consider the full range of artistic approaches that could be used in a particular site, public art can be permanent or temporary; the following categories summarise popular approaches to public art. Sculpture Sculptural works are not solely about creating a precious piece of art but creating a piece which extends the sculpture into the wider landscape linking it with the environment and focussing attention on what is already there. -

Resource What Is Modern and Contemporary Art

WHAT IS– – Modern and Contemporary Art ––– – –––– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ––– – – – – ? www.imma.ie T. 00 353 1 612 9900 F. 00 353 1 612 9999 E. [email protected] Royal Hospital, Military Rd, Kilmainham, Dublin 8 Ireland Education and Community Programmes, Irish Museum of Modern Art, IMMA THE WHAT IS– – IMMA Talks Series – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ? There is a growing interest in Contemporary Art, yet the ideas and theo- retical frameworks which inform its practice can be complex and difficult to access. By focusing on a number of key headings, such as Conceptual Art, Installation Art and Performance Art, this series of talks is intended to provide a broad overview of some of the central themes and directions in Modern and Contemporary Art. This series represents a response to a number of challenges. Firstly, the 03 inherent problems and contradictions that arise when attempting to outline or summarise the wide-ranging, constantly changing and contested spheres of both art theory and practice, and secondly, the use of summary terms to describe a range of practices, many of which emerged in opposition to such totalising tendencies. CONTENTS Taking these challenges into account, this talks series offers a range of perspectives, drawing on expertise and experience from lecturers, artists, curators and critical writers and is neither definitive nor exhaustive. The inten- What is __? talks series page 03 tion is to provide background and contextual information about the art and Introduction: Modern and Contemporary Art page 04 artists featured in IMMA’s exhibitions and collection in particular, and about How soon was now? What is Modern and Contemporary Art? Contemporary Art in general, to promote information sharing, and to encourage -Francis Halsall & Declan Long page 08 critical thinking, debate and discussion about art and artists. -

Museum Quarter

NAVAN ROAD DRUMCONDRA NEPHIN ROAD DALYMOUNT PARK CLONLIFFE ROAD 14 PHOENIX PARK & JONES ROAD EAST WALL ROAD CROKE GAA DART NORTH CIRCULAR ROAD PARK MUSEUM MUSEUM QUARTER LEINSTER AVE DORSET STREET BELVEDERE RD U RUSSELL ST PP E R G A R D NORTH CIRCULAR ROAD IN E R S NORTH STRAND ROAD STONEY RD T NO VENUE PG MOUNTJOY PORTLAND ROW D MIDDLE GARDINERSQUARE ST A 2 20 O 1 3 Walls Gallery 16 R FREDERICK ST NORTH SUMMERHILL T 2 Áras an Uachtaráin 16 S GRANGE GORMAN LWR GORMAN GRANGE 8 E 3 Brown Bag Films 16 W NORTH GT GEORGES ST 4 Damn Fine Print 16 EAST WALL ROAD LUAS RUTLAND CALEDON CT 5 The Darkroom 17 JAMES JOYCE STREET PARNELL SQ. EAST DART CHURCHST MARY’S ROAD RD 6 Dr Steevens’ Hospital (HSE) 17 16 OXMANTOWN ROAD LOWER GARDINER ST MORNING STAR AVE SEAN MACDERMOTT ST DORSET STREET PARNELL STREET SEVILLE PLACE 7 The elbowroom 17 PARNELL SQ. WEST HALLIDAY RD 13 PARNELL HENRIETTA ST MARLBOROUGH ST MANOR STREET 19 GRANGE GORMAN LWR SQUARE 8 Grangegorman Development 17 T DOMINICK ST LWR S 1 Agency CONNOLLY H C PROVOST ROW STATION KILLAN RD 9 The Greek Orthodox Community of 18 R FOLEY ST EAST ROAD U K LUAS H IN Ireland 7 G C ’S MANOR PLACE I MORNING STAR AVE STAR MORNING N INFIRMARY ROAD BOLTON ST N 10 IMMA (Irish Museum of Modern Art) 18 S CATHEDRAL ST S 4 5 T 14 O’CONNELL ST UPPER SHERRIF ST 11 Irish Railway Record Society (IRRS) 18 CHESTERFIELD AVENUE CAVALRY ROW BRUNSWICK ST. -

VAN JA 2021.Indd

Lismore Castle Arts ALICIA REYES MCNAMARA Curated by Berlin Opticians LIGHT AND LANGUAGE Nancy Holt with A.K. Burns, Matthew Day Jackson, Dennis McNulty, Charlotte Moth and Katie Paterson. Curated by Lisa Le Feuvre 28 MARCH - 10 JULY - 10 OCTOBER 2021 22 AUGUST 2021 LISMORE CASTLE ARTS, LISMORE CASTLE ARTS: ST CARTHAGE HALL LISMORE CASTLE, LISMORE, CHAPEL ST, LISMORE, CO WATERFORD, IRELAND CO WATERFORD, IRELAND WWW.LISMORECASTLEARTS.IE +353 (0)58 54061WWW.LISMORECASTLEARTS.IE Image: Alicia Reyes McNamara, She who comes undone, 2019, Oil on canvas, 110 x 150 cm. Courtesy McNamara, She who comes undone, 2019, Oil on canvas, of the artist Image: Alicia Reyes and Berlin Opticians Gallery. Nancy Holt, Concrete Poem (1968) Ink jet print on rag paper taken from original 126 format23 transparency x 23 in. (58.4 x 58.4 cm.). 1 of 5 plus AP © Holt/Smithson Foundation, Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. VAN The Visual Artists’ Issue 4: BELFAST PHOTO FESTIVAL PHOTO BELFAST FILM SOCIETY EXPERIMENTAL COLLECTION THE NATIONAL COLLECTIVE ARRAY Inside This Issue July – August 2021 – August July News Sheet News A Visual Artists Ireland Publication Ireland A Visual Artists Contents Editorial On The Cover WELCOME to the July – August 2021 Issue of within the Irish visual arts community is The Visual Artists’ News Sheet. outlined in Susan Campbell’s report on the Array Collective, Pride, 2019; photograph by Laura O’Connor, courtesy To mark the much-anticipated reopening million-euro acquisition fund, through which Array and Tate Press Offi ce. of galleries, museums and art centres, we 422 artworks by 70 artists have been add- have compiled a Summer Gallery Guide to ed to the National Collection at IMMA and First Pages inform audiences about forthcoming exhi- Crawford Art Gallery. -

GREEN PAPER Page 1

AMERICANS FOR THE ARTS PUBLIC ART NETWORK COUNCIL: GREEN PAPER page 1 Why Public Art Matters Cities gain value through public art – cultural, social, and economic value. Public art is a distinguishing part of our public history and our evolving culture. It reflects and reveals our society, adds meaning to our cities and uniqueness to our communities. Public art humanizes the built environment and invigorates public spaces. It provides an intersection between past, present and future, between disciplines, and between ideas. Public art is freely accessible. Cultural Value and Community Identity American cities and towns aspire to be places where people want to live and want to visit. Having a particular community identity, especially in terms of what our towns look like, is becoming even more important in a world where everyplace tends to looks like everyplace else. Places with strong public art expressions break the trend of blandness and sameness, and give communities a stronger sense of place and identity. When we think about memorable places, we think about their icons – consider the St. Louis Arch, the totem poles of Vancouver, the heads at Easter Island. All of these were the work of creative people who captured the spirit and atmosphere of their cultural milieu. Absent public art, we would be absent our human identities. The Artist as Contributor to Cultural Value Public art brings artists and their creative vision into the civic decision making process. In addition the aesthetic benefits of having works of art in public places, artists can make valuable contributions when they are included in the mix of planners, engineers, designers, elected officials, and community stakeholders who are involved in planning public spaces and amenities. -

What Is Public Art?

POLICIES & PROCEDURES MANUAL Updated: February 2015 Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 4 What is Public Art? ................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 CITY-FUNDED PUBLIC ART ............................................................................................................... 5 Summary of the Process .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Funding Policies ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Funding Procedures ................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Public Art Manager’s Role ..................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Generating Ideas for Public Art in Capital Projects............................................................................................................................. 8 Methods of Selecting Public Art .......................................................................................................................................................... -

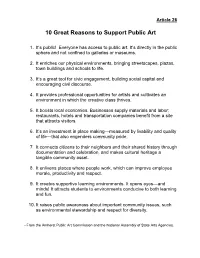

10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art

Article 26 10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art 1. It’s public! Everyone has access to public art. It’s directly in the public sphere and not confined to galleries or museums. 2. It enriches our physical environments, bringing streetscapes, plazas, town buildings and schools to life. 3. It’s a great tool for civic engagement, building social capital and encouraging civil discourse. 4. It provides professional opportunities for artists and cultivates an environment in which the creative class thrives. 5. It boosts local economies. Businesses supply materials and labor; restaurants, hotels and transportation companies benefit from a site that attracts visitors. 6. It’s an investment in place making—measured by livability and quality of life—that also engenders community pride. 7. It connects citizens to their neighbors and their shared history through documentation and celebration, and makes cultural heritage a tangible community asset. 8. It enlivens places where people work, which can improve employee morale, productivity and respect. 9. It creates supportive learning environments. It opens eyes—and minds! It attracts students to environments conducive to both learning and fun. 10. It raises public awareness about important community issues, such as environmental stewardship and respect for diversity. --From the Amherst Public Art Commission and the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. The Amherst Public Art Commission Why Public Art for Amherst? Public art adds enormous value to the cultural, aesthetic and economic vitality of a community. It is now a well-accepted principle of urban design that public art contributes to a community’s identity, fosters community pride and a sense of belonging, and enhances the quality of life for its residents and visitors. -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 689 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. Anthony Sheehy, Mike at the Hunt Museum, OUR READERS Steve Whitfield, Stevie Winder, Ann in Galway, Many thanks to the travellers who used the anonymous farmer who pointed the way to the last edition and wrote to us with help- Knockgraffon Motte and all the truly delightful ful hints, useful advice and interesting people I met on the road who brought sunshine anecdotes: to the wettest of Irish days. Thanks also, as A Andrzej Januszewski, Annelise Bak C Chris always, to Daisy, Tim and Emma. Keegan, Colin Saunderson, Courtney Shucker D Denis O’Sullivan J Jack Clancy, Jacob Catherine Le Nevez Harris, Jane Barrett, Joe O’Brien, John Devitt, Sláinte first and foremost to Julian, and to Joyce Taylor, Juliette Tirard-Collet K Karen all of the locals, fellow travellers and tourism Boss, Katrin Riegelnegg L Laura Teece, Lavin professionals en route for insights, information Graviss, Luc Tétreault M Marguerite Harber, and great craic. -

Public Art Policy

CITY OF GILROY PUBLIC ART POLICY VISION STATEMENT: The City of Gilroy’s Public Art Committee promotes a bold vision which exemplifies the City’s creativity and energy shaping the visual environment of our community. PURPOSE: The City of Gilroy (City) recognizes the importance of Public Art to the cultural, educational and economic well-being of its diverse population. These guidelines are for the purpose of establishing policies and procedures for implementing Public Art as recommended in the Arts & Culture Commission’s Cultural Plan, developed in 1997, and 1999 General Plan Update. GOALS: To promote the City’s interest in its aesthetic environment. To establish the Public Art Committee as an advisory committee to the Arts and Culture Commission to be responsible for developing the Public Art Plan; ensuring the quality of artworks created under the plan; and, developing budgets, funding strategies and scope of individual Public Art projects. To create an enhanced visual environment within the City and provide City residents with the opportunity to live with Public Art. To help build pride in our City and among its citizens. To promote tourism and economic vitality of the City by enhancing the City’s public facilities and surroundings through the incorporation of Public Art. To encourage creative collaboration among community members. To encourage the creation of quality Public Art throughout the City by promoting locally, regionally, nationally and internationally recognized artists. To educate, preserve, reflect and celebrate the rich, unique history and cultural diversity of the City and its citizens. To promote and encourage art viewed by the public in all of the City’s communities and neighborhoods and to support the residents’ involvement in determining the character of their City. -

WILLIE DOHERTY B

WILLIE DOHERTY b. 1959, Derry, Northern Ireland Lives and works in Derry EDUCATION 1978-81 BA Hons Degree in Sculpture, Ulster Polytechnic, York Street 1977-78 Foundation Course, Ulster Polytechnic, Jordanstown FORTHCOMING & CURRENT EXHIBITIONS 2020 ENDLESS, Kerlin Gallery, online viewing room, (27 May - 16 June 2020), (solo) SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Remains, Regional Cultural Centre, Letterkenny, Ireland Inquieta, Galeria Moises Perez de Albeniz, Madrid, Spain 2017 Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich, Switzerland Remains, Art Sonje Center, Seoul, South Korea No Return, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA Loose Ends, Matt’s Gallery, London, UK 2016 Passage, Alexander and Bonin, New York Lydney Park Estate, Gloucestershire, presented by Matt’s Gallery + BLACKROCK Loose Ends, Regional Centre, Letterkenny; Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, Ireland Home, Villa Merkel, Germany 2015 Again and Again, Fundaçao Calouste Gulbenkian, CAM, Lisbon Panopticon, Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA), Salt Lake City 2014 The Amnesiac and other recent video and photographic works, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA UNSEEN, Museum De Pont, Tilburg The Amnesiac, Galería Moisés Pérez de Albéniz, Madrid REMAINS, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin 2013 UNSEEN, City Factory Gallery, Derry Secretion, Neue Galerie, Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel Secretion, The Annex, IMMA, Dublin Without Trace, Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich 2012 Secretion, Statens Museum for Kunst, National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen LAPSE, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin Photo/text/85/92, Matts Gallery, London One Place Twice, -

Dorothy Cross Dorothy Cross B

Kerlin Gallery Dorothy Cross Dorothy Cross b. 1956, Cork, Ireland Like many of Dorothy Cross’ sculptures, Family (2005) and Right Ball and Left Ball (2007) sees the artist work with found objects, transforming them with characteristic wit and sophistication. Right Ball and Left Ball (2007) presents a pair of deflated footballs, no longer of use, their past buoyancy now anchored in bronze. Emerging from each is a cast of the artist’s hands, index finger extended upwards in a pointed gesture suggesting optimism or aspiration. In Family (2005) we see the artist’s undeniable craft and humour come together. Three spider crabs were found, dead for some time but still together. The intricacies of their form and the oddness of their sideways maneuvres forever cast in bronze. The ‘father’ adorned with an improbable appendage also pointing upwards and away. --- Working in sculpture, film and photography, Dorothy Cross examines the relationship between living beings and the natural world. Living in Connemara, a rural area on Ireland’s west coast, the artist sees the body and nature as sites of constant change, creation and destruction, new and old. This flux emerges as strange and unexpected encounters. Many of Cross’ works incorporate items found on the shore, including animals that die of natural causes. During the 1990s, the artist produced a series of works using cow udders, which drew on the animals' rich store of symbolic associations across cultures to investigate the construction of sexuality Dorothy Cross Right Ball and Left Ball 2007 cast bronze, unique 34 x 20 x 19 cm / 13.4 x 7.9 x 7.5 in 37 x 19 x 17 cm / 14.6 x 7.5 x 6.7 in DC20407A Dorothy Cross Family 2005 cast bronze edition of 2/4 dimensions variable element 1: 38 x 19 x 20 cm / 15 x 7.5 x 7.9 in element 2: 25 x 24 x 13 cm / 9.8 x 9.4 x 5.1 in element 3: 16 x 15 x 13 cm / 6.3 x 5.9 x 5.1 in DC17405-2/4 Dorothy Cross b.