History of State and Church Relationships in Latvia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ECFG-Latvia-2021R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: A Latvian musician plays a popular folk instrument - the dūdas (bagpipe), photo courtesy of Culture Grams, ProQuest). The guide consists of 2 parts: ECFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on the Baltic States. Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Latvia Latvian society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre-deployment training (Photo: A US jumpmaster inspects a Latvian paratrooper during International Jump Week hosted by Special Operations Command Europe). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

University of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level)

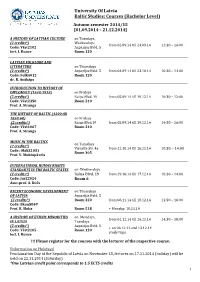

University Of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level) Autumn semester 2014/15 [01.09.2014 – 21.12.2014] A HISTORY OF LATVIAN CULTURE on Tuesdays, (2 credits*) Wednesdays from 02.09.14 till 24.09.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst2102 Azpazijas Bvld. 5 lect. I. Runce Room 120 LATVIAN FOLKLORE AND LITERATURE on Thursdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. 5 from 04.09.14 till 23.10.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: Folk4012 Room 120 dr. R. Auškāps INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF DIPLOMACY (1648-1918) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 10:30 – 12:00 Code: Vēst2350 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga THE HISTORY OF BALTIC (1200 till 1850-60) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd.19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 14:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst1067 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga MUSIC IN THE BALTICS on Tuesdays (2 credits*) Visvalža Str. 4a from 21.10.14 till 16.12.14 10:30. – 14:00 Code : MākZ1031 Room 305 Prof. V. Muktupāvels INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARTS IN THE BALTIC STATES on Wednesdays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 29.10.14 till 17.12.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: JurZ2024 Room 6 Asoc.prof. A. Kučs RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT on Thursdays OF LATVIA Azpazijas Bvld. 5 (2 credits*) Room 320 from 06.11.14 till 18.12.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Ekon5069 Prof. B. Sloka Room 518 + Monday, 10.11.14 A HISTORY OF ETHNIC MINORITIES on Mondays, from 01.12.14 till 16.12.14 14:30 – 18:00 IN LATVIA Tuesdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. -

THE RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH Department for External Church Relations

THE RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH Department for External Church Relations His Holiness Patriarch Kirill meets with President of the Latvian Republic Valdis Zatlers On 20 December 2010, the Primate of the Russian Orthodox Church met with the President of the Latvian Republic, Valdis Zatlers. The meeting took place at the Patriarch's working residence in Chisty sidestreet, Moscow. The Latvian President was accompanied by his wife Ms. Lilita Zatlers; Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Latvian Republic to the Russian Federation Edgars Skuja; head of the President's Chancery Edgars Rinkevichs; state secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Andris Teikmanis; Riga Mayor Nil Ushakov; foreign relations advisor to the President, Andris Pelsh; and advisor to the President, Vasily Melnik. Taking part in the meeting were also Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk, chairman of the Moscow Patriarchate's Department for External Church Relations; Metropolitan Alexander of Riga and All Lat via; and Bishop Alexander of Daugavpils. Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Russian Federation to the Latvian Republic A. Veshnyakov and the third secretary of the Second European Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs S. Abramkin represented the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. His Holiness Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia cordially greeted the President of Latvia and his suite, expressing his hope for the first visit of Valdis Zatlers to Moscow to serve to the strengthening of friendly relations between people of the two countries. His Holiness noted with appreciation the high level of relations between the Latvian Republic and the Russian Orthodox Church. "It is an encouraging fact that the Law on the Latvian Orthodox Church has come into force in Latvia in 2008. -

Same-Sex Relationships: Why Do Many Latvian Politicians Resist Them?

SSE Riga Student Research Papers 2021 : 2 (234) SAME-SEX RELATIONSHIPS: WHY DO MANY LATVIAN POLITICIANS RESIST THEM? Authors: Daniela Gerda Baranova Samanta Mežmale ISSN 1691-4643 ISBN 978-9984-822-58-7 May 2021 Riga Same-Sex Relationships: Why Do Many Latvian Politicians Resist Them? Daniela Gerda Baranova and Samanta Mežmale Supervisor: Xavier Landes May 2021 Riga Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................. 5 Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 7 2. Literature Review .................................................................................................................. 9 2.1. LGBT in the World ......................................................................................................... 9 2.1.1. LGBT Movement ....................................................................................................... 9 2.1.2. Legislation ................................................................................................................ 10 2.1.3. Sexual orientation discrimination and homophobia ................................................. 11 2.1.4. Supporting organisations ......................................................................................... -

Canon Law of Eastern Churches

KB- KBZ Religious Legal Systems KBR-KBX Law of Christian Denominations KBR History of Canon Law KBS Canon Law of Eastern Churches Class here works on Eastern canon law in general, and further, on the law governing the Orthodox Eastern Church, the East Syrian Churches, and the pre- Chalcedonean Churches For canon law of Eastern Rite Churches in Communion with the Holy See of Rome, see KBT Bibliography Including international and national bibliography 3 General bibliography 7 Personal bibliography. Writers on canon law. Canonists (Collective or individual) Periodicals, see KB46-67 (Christian legal periodicals) For periodicals (Collective and general), see BX100 For periodicals of a particular church, see that church in BX, e.g. BX120, Armenian Church For periodicals of the local government of a church, see that church in KBS Annuals. Yearbooks, see BX100 Official gazettes, see the particular church in KBS Official acts. Documents For acts and documents of a particular church, see that church in KBS, e.g. KBS465, Russian Orthodox Church Collections. Compilations. Selections For sources before 1054 (Great Schism), see KBR195+ For sources from ca.1054 on, see KBS270-300 For canonical collections of early councils and synods, both ecumenical/general and provincial, see KBR205+ For document collections of episcopal councils/synods and diocesan councils and synods (Collected and individual), see the church in KBS 30.5 Indexes. Registers. Digests 31 General and comprehensive) Including councils and synods 42 Decisions of ecclesiastical tribunals and courts (Collective) Including related materials For decisions of ecclesiastical tribunals and courts of a particular church, see that church in KBS Encyclopedias. -

Russian Copper Icons Crosses Kunz Collection: Castings Faith

Russian Copper Icons 1 Crosses r ^ .1 _ Kunz Collection: Castings Faith Richard Eighme Ahlborn and Vera Beaver-Bricken Espinola Editors SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Stnithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsoniar) Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the worid of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the worid. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where tfie manuscripts are given substantive review. -

A Reconstructed Indigenous Religious Tradition in Latvia

religions Article A Reconstructed Indigenous Religious Tradition in Latvia Anita Stasulane Faculty of Humanities, Daugavpils University, Daugavpils LV-5401, Latvia; [email protected] Received: 31 January 2019; Accepted: 11 March 2019; Published: 14 March 2019 Abstract: In the early 20th century, Dievtur¯ıba, a reconstructed form of paganism, laid claim to the status of an indigenous religious tradition in Latvia. Having experienced various changes over the course of the century, Dievtur¯ıba has not disappeared from the Latvian cultural space and gained new manifestations with an increase in attempts to strengthen indigenous identity as a result of the pressures of globalization. This article provides a historical analytical overview about the conditions that have determined the reconstruction of the indigenous Latvian religious tradition in the early 20th century, how its form changed in the late 20th century and the types of new features it has acquired nowadays. The beginnings of the Dievturi movement show how dynamic the relationship has been between indigeneity and nationalism: indigenous, cultural and ethnic roots were put forward as the criteria of authenticity for reconstructed paganism, and they fitted in perfectly with nativist discourse, which is based on the conviction that a nation’s ethnic composition must correspond with the state’s titular nation. With the weakening of the Soviet regime, attempts emerged amongst folklore groups to revive ancient Latvian traditions, including religious rituals as well. Distancing itself from the folk tradition preservation movement, Dievtur¯ıba nowadays nonetheless strives to identify itself as a Latvian lifestyle movement and emphasizes that it represents an ethnic religion which is the people’s spiritual foundation and a part of intangible cultural heritage. -

Baltic Unity Within European Unity – Why Myth, Not Reality?

1 Baltic Unity within European Unity – why Myth, not Reality? In recent years a debate about development of the European Union (EU) has become hugely important. There are diverse views on the direction of federalism, which the President of the European Commission J. M. D. Barroso is passionately promoting: “Let’s not be afraid of the words: we will need to move towards a federation of nation states. This is what we need. This is our political horizon.”1 As a consequence of such ambitious plans, the question of national identity and independence has become crucial. However, less attention has been paid to the problem of regional cooperation and the effects of already existing European integration on it, which is exactly what this report aims at. In mass media one can often hear about an entity called ‘the Baltic States‘. This union of three states Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania has cooperated quite a lot in the two last decades of 20th century, however, now the importance of cooperation seems to be in decline. The Baltic unity in the European unity (i.e. EU) is a myth because of two reasons: passive effect of the integration in the EU, when the European unity indirectly and unintentionally influences the cooperation among the Baltic States, and active effect of the policies of the EU, when they have deliberate impact on the Baltic Unity. Baltic Unity before the EU In order to indicate why Baltic unity is impossible in the context of integrated Europe, it is necessary to recall the common aim of Baltic cooperation before the accession to the European Union. -

Between National and Academic Agendas Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940

BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Other titles in the same series Södertörn Studies in History Git Claesson Pipping & Tom Olsson, Dyrkan och spektakel: Selma Lagerlöfs framträdanden i offentligheten i Sverige 1909 och Finland 1912, 2010. Heiko Droste (ed.), Connecting the Baltic Area: The Swedish Postal System in the Seventeenth Century, 2011. Susanna Sjödin Lindenskoug, Manlighetens bortre gräns: tidelagsrättegångar i Livland åren 1685–1709, 2011. Anna Rosengren, Åldrandet och språket: En språkhistorisk analys av hög ålder och åldrande i Sverige cirka 1875–1975, 2011. Steffen Werther, SS-Vision und Grenzland-Realität: Vom Umgang dänischer und „volksdeutscher” Nationalsozialisten in Sønderjylland mit der „großgermanischen“ Ideologie der SS, 2012. Södertörn Academic Studies Leif Dahlberg och Hans Ruin (red.), Fenomenologi, teknik och medialitet, 2012. Samuel Edquist, I Ruriks fotspår: Om forntida svenska österledsfärder i modern historieskrivning, 2012. Jonna Bornemark (ed.), Phenomenology of Eros, 2012. Jonna Bornemark och Hans Ruin (eds), Ambiguity of the Sacred, 2012. Håkan Nilsson (ed.), Placing Art in the Public Realm, 2012. Lars Kleberg and Aleksei Semenenko (eds), Aksenov and the Environs/Aksenov i okrestnosti, 2012. BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Södertörns högskola Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image, taken from Latvijas Universitāte Illūstrācijās, p. 10. Gulbis, Riga, 1929. Cover: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson and Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Studies in History 13 ISSN 1653-2147 Södertörn Academic Studies 51 ISSN 1650-6162 ISBN 978-91-86069-52-0 Contents Foreword ...................................................................................................................................... -

The Impact of Covid-19 on Orthodox Groups and Believers in Russia

The Impact of Covid-19 on Orthodox Groups and Believers in Russia Anastasia V. Mitrofanova Abstract This chapter intends to discover how Orthodox groups and believers of different ideological orientations in Russia reacted to the 2020 world health crisis. Its fo- cus lies on the groups and individual believers from the field of Russian Ortho- doxy who could be labelled as ‘fundamentalists’. Therefore, an analysis of the offi- cial ecclesiastical reaction to the pandemic will be provided, that underlines how some contradictory messages from above caused significant numbers of believers to sympathize with the so called “corona-dissidents” within the Church. Under the topic ‘dissidents’, various other groups apart from the fundamentalists such as the moderate traditionalists, liberals, or individuals who usually follow the mainstream ecclesiastical opinion, can be subsumed. Furthermore, it could be observed that fundamentalists mostly discuss themes that might be common for all “dissidents”, although they are more open towards their criticism in view of the mainstream reactions. They stick to the assumption that both mundane and ecclesiastical leaders have discredited themselves and need to be replaced. Keywords: Orthodox Christianity, Covid-19, Ecclesiastical Lockdown, Corona- Dissidents, Fundamentalist Networks, Traditionalism, Russian Orthodox Church 1. Introduction This chapter intends to discover how Orthodox groups and believers of different ideological orientations in Russia reacted to the 2020 world health crisis. It focusses on groups and individuals who are labelled as “fundamentalists”, because they be- lieve for instance that the entire socio-political life should be changed in terms of 48 AnastasiaV.Mitrofanova collective religious salvation.1 Apart from the official position of the Moscow Pa- triarchate («the patriarchal platform»), Irina Papkova distinguishes three informal political ideologies within the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC): liberal (associated with intra-church movements initiated by late Fr. -

Eastern Christianity and Politics: Church-State Relations in Ukraine

CAMBRIDGE INSTITUTE ON RELIGION & INTERNATIONAL STUDIES Eastern Christianity and Politics: Church-State Relations in Ukraine Lucian N. Leustean | 11 January 2016 Cambridge Institute on Religion & International Studies Clare College Trinity Lane CB2 1TL Cambridge United Kingdom CIRIS.org.uk This report was commissioned by CIRIS on behalf of the Transatlantic Policy Network on Religion and Diplomacy (TPNRD). CIRIS’s role as the secretariat for the TPNRD is a partnership with George Mason University and is funded by the Henry Luce Foundation. 1 Eastern Christianity and Politics: Church-State Relations in Ukraine On 23 June 2001, Pope John Paul II arrived in Kyiv for a five-day state visit on the invitation of President Leonid Kuchma. Upon arrival, his first words uttered in Ukrainian were: ‘Let us recognise our faults as we ask forgiveness for the errors committed in both the distant and recent past. Let us in turn offer forgiveness for the wrongs endured. Finally, with deep joy, I have been able to kiss the beloved soil of Ukraine. I thank God for the gift that he has given me today’.1 The Pope’s words, which combined religious diplomacy with political reconciliation, were received with scepticism by his counterparts in Kyiv and Moscow. A few weeks earlier, Metropolitan Vladimir, head of the largest Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate), asked the Pope to cancel his visit, an unusual request which was regarded as breaching the Vatican protocol. Furthermore, Patriarch Aleksii II of the Russian Orthodox Church declined meeting the Pope either in Moscow, or in Kyiv, as long as ‘the Greek-Catholic war continues against Orthodox believers in Ukraine and until the Vatican stops its expansion into Russia, Belarus and Ukraine’.2 The Patriarch’s reference to ‘a war’ between Orthodox and Catholics, and continuing religious tension in Ukraine, are part of the wider and complex trajectory of church- state relations within the Eastern Christian world which has developed after the end of the Cold War. -

Couronians | Semigallians | Selonians

BALTS’ ROAD, THE COURONIAN ROUTE SEGMENT Route: Rucava – Liepāja – Grobiņa – Jūrkalne – Alsunga – Kuldīga – Ventspils – Talsi – Valdemārpils – Sabile – Saldus – Embūte – Mosėdis – Plateliai – Kretinga – Klaipėda – Palanga – Rucava Duration: 3–4 days. Length about 790 km In ancient times, Couronians lived on the coast of the Baltic Sea. At that time, the sea and rivers were an important waterway that inuenced their way of life and interaction with neighbouring nations. You will nd out about this by taking the circular Couronian Route Segment. Peaceful deals were made during trading. Merchants from faraway lands Macaitis, Tērvete Tourism Information Centre, Zemgale Planning Region. Planning Zemgale Centre, Information Tourism Tērvete Macaitis, were tempted to visit the shores of the Baltic Sea looking for the northern gold – Photos: Līva Dāvidsone, Artis Gustovskis, Arvydas Gurkšnis, Denisas Nikitenka, Mindaugas Mindaugas Nikitenka, Denisas Gurkšnis, Arvydas Gustovskis, Artis Dāvidsone, Līva Photos: Publisher: Kurzeme Planning Region, Zemgale Planning Region 2019 Region Planning Zemgale Region, Planning Kurzeme Publisher: amber. To nd out more about amber, visit the Palanga Amber Museum (40) Centre, National Regional Development Agency in Lithuania. in Agency Development Regional National Centre, and the Liepāja Crafts House (6). Ancient Couronian boats, the barges, are Authors: Kurzeme Planning Region, Zemgale Planning Region, Šiauliai Tourism Information Information Tourism Šiauliai Region, Planning Zemgale Region, Planning Kurzeme Authors: